Open Sheds Used for What?: An interview with Cecilia & Marina Resende Santos

Open Sheds Used for What? conjures more questions than answers, which is precisely where its magic comes from—that, and its devotion in spirit and design to collaboration, community, and experimentation.…

Open Sheds Used for What? conjures more questions than answers, which is precisely where its magic comes from—that, and its devotion in spirit and design to collaboration, community, and experimentation. The brainchild of collaborators and twin sisters Cecilia and Marina Resende Santos, Open Sheds is a nomadic project that is itinerant and ephemeral, springing forth from an octagonal metal frame originally built by Jesús Hilario Reyes and Leah Solomon for their performance at the opening of “Shut Up Stone Mountain,” at Co-Prosperity on June 7, 2019. This deceptively simple frame is more than a ‘blank canvas,’ larger and more expansive than a substrate that can be built upon. It is a seed, it is potential, it is what extends from it and out of it, with or without it.

In its simplest terms, Open Sheds is a structure that has been built and deconstructed in three different locations around Chicago, with various artists altering, adding to, and transforming its form through intervention, performance, and other means. At least 15 artists have been involved with the project (and more indirectly, I’m sure). However, the project is always in a ‘public’ space, that is to say, out in the open in a way the public art, or perhaps more similarly, murals are. Like murals and street art, Open Sheds culminates in locations that are often in precarious states, not quite public or private.

The project began in May of this year and now lives (semi) permanently at The Franklin in Garfield Park until the end of 2020, a fitting arena for the project as The Franklin is also a structure that plays with public and private, inside and outside. Visiting this iteration of Open Sheds myself, I assumed I knew what to expect, having seen photos of past iterations of the project. How quickly we forget the possibilities and potentials that come along with a new space, new people! Context within space changes everything. Within The Franklin (located in the backyard of artist Edra Soto), I found a structure with seemingly endless entry points, obscuring my perception of space and the intended path into/around the work. This obscuring, stretching, bending, and warping of space and perception, is exactly the “function” of Open Sheds. The work questions space, questions intention, questions function, and certainly questions possibility.

Christina Nafziger: What is Open Sheds Used for What? and who is involved in the project? How did it begin?

Cecilia Resende Santos: Open Sheds Used for What? is a dynamic installation; an ongoing series of interventions on and around a structure located in open urban spaces. Marina and I run the project, but many more people have been involved: participating artists; friends and neighbors who help move, assemble, and install; and anyone who comes into contact with the interventions.

Marina Resende Santos: The idea of a gradual construction process had two conceptual anchors. One; this was an “open construction site,” where the process of building up was visible, could be appreciated as if in slow motion, and invited participation that intervened in the building that already is even before the construction is “finished.” We wanted to degrade the idea of the finished product. With that, construction became a performative process; indeed, our first action in the space would have been a movement piece emphasizing the gestures of construction (while, indeed, building). Two: To me, that inconclusiveness became, too, a way to criticize the way that urban infrastructure and architectural projects traditionally conceive of and change space: constructing means closing off, creating and determining the possibilities of a space, and ultimately reserving it for some people and not others. Each moment of Open Sheds Used for What? was already a space that afforded different uses, and that space itself was bound to change the next week, and there is nothing tragic about this end or this transformation as long as the built structure remains alive.

Cecilia Resende Santos: The construction process would be something like a mutirão, by which occupants and neighbors collectively build a space. At each stage of enclosure, we would invite collaborators to intervene, make installations, host events, workshops, anything: to just use the space. We got relatively far into planning this and were in touch with the University of Chicago to host it in Hyde Park, but plans fell through. We restarted discussions in May when we got in touch with Jess Bass about her Kedzie Stretch project, a potential host for Open Sheds, and started thinking about using the octagonal frame that was leftover from a performance by Jesus Hilario Reyes and Leah Solomon at Co-Prosperity in 2019. Considering pandemic conditions, and our plans to be in an unauthorized public space or vacant lot, the structure would allow us to be more nimble and mobile. We put the process on pause for a bit when the protests against police brutality started happening and reconsidered. Eventually, we decided to place the structure in a vacant lot in Bridgeport, close to where Marina lived and worked.

CN: The project being nomadic, where has it been located so far? How many iterations have existed and who are some of the artists you’ve worked with?

CRS: So far, the project has been located in an empty lot on 34th Place and Morgan in Bridgeport (currently for sale by Landmark Properties), in and around El Paseo Community Garden in Pilsen, and now in the backyard of The Franklin in Garfield Park. The moves were not planned, but somehow flowed organically as needed–one of the principles and lessons of this project, overall. There have been about 20 iterations, including performances, events, and interventions by Marina and me. We have worked with some 15 participants, plus many more collaborators along the way: Hanna Gregor, Graham Livingtson, Maya Nguen, Unyimeabasi Udoh, Breanne Johnson, Elizabeth Lindberg, Gabriel Chalfin-Piney, Aida Ramirez, Kayla Taylor, Veronica Anne Salinas, John Thomure (who made a spontaneous, uninvited intervention), Gabriel Moreno, Courtney Mackedanz, Jacob Lindgren, and Saffronia Downing.

CN: Open Sheds’ website states that it is “an experiment in the open construct of space.” I’m interested in how you are implementing the project as an experiment. How does the project challenge and probe the notion of “public” space? What questions does it pose?

CRS: The project is an experiment for us; an open-ended endeavor that constantly changes and responds to local conditions in a space—public, semi-public, occupied—that we cannot fully control. Therefore, it unfolds with ad hoc adaptations, planning as needed; it has to be responsive, agile, and adaptable. It is difficult, in fact, to remain attached to a single original concept, as the project takes different shapes and functions in response to changing circumstances and new opportunities. It is also an experiment for each artist, as a challenge to create something in the public realm, and an opportunity to develop existing projects or thinking. Projects are mostly conceived on-site, installed quickly, with available resources.

The relationship to and definition of the public, though always at the center of the project, is in fact in question for me. Is it public because you can look at it, relate to it, intervene in it (from the quintessential public realm of the street)? Does placing something to look at, relate to, and intervene in make it public, i.e. of the people? Does making something happen in a space make this space …exist? As a place? A visible object? An actionable object?

In some instances, this question was made much more concrete, as in the private, though vacant, property we occupied at first. There, the project probed the boundary between the public and the private. In its entire arc, the project also highlights the different relations the object can create in different situations of visibility and ownership (two dimensions of the public, if you will): the visible but denied space of the empty lot; the unused space that is of/for the people in the community garden; the domestic-made-“public” space at the Franklin.

MRS: The notion of “experiment” relates to the many open ends in this project. How will people in the neighborhood react? The owners? No reaction at all was always a possibility. The other uncertainty that had to develop with the process were the interventions themselves: what artists would come up with, how they would intend to transform or use this space, and how that would actually manifest. We addressed this built-in spontaneity as an experiment, or as a test. That is, there was a factor of testing out reactions and possibilities animating the project.

The word “experiment” refers to an “experimental” process, architecture, or work of art.

We discovered the answers to our questions by talking about the questions themselves. We questioned the definition of the “public space” and the permissions attendant to open spaces in the urban environment. The vacant lot in Bridgeport was legally not a public space. It could, however, be understood as public, or as a form of sly “commons,” insofar as people could cross through it, play in it, sit on the pile of stones to (apparently) eat oranges and strawberries and drink juice. People could also, as we did for many weeks, install a six-foot-tall frame and spend time dancing, having a picnic, or working there. However, as a standard vacant lot (100 x 25ft), it was also not the place that drew in the most passersby. There is already a code to avoid it, to simply not see it in the city.

When workers came to clean the lot, they took notice of the frame and dumped it. They did that twice. Later when we were installing cladding material (sod in Graham Livingston’s piece “molt”), the owner came by and told me that he had been asking the workers to take it down, that he had already ordered the fencing of the lot, and that he thought that [it could have been] a homeless person who had been putting up that structure–or any other threat to his right of possession. That fear was the exact moment of privatization of space. (He also said that, if he knew it was an art project, he wouldn’t have done it.) Near El Paseo, in East Pilsen, we had a very different experience of “public” and “open” space, and of art in a public space.

CN: As part of Open Sheds, you organized various performances throughout the lifespan of each iteration. Can you talk a bit about these performances? Tell me about one specific performance that interacted with the structure in a way that embodied the concept of “open space”?

CRS: There have been a few performances organized around the structure, each time by the initiative of the artists. While installations have their power in their presence (the just being there, and how that transforms their space like a centrifugal force), performances and/or time-based events generate an audience, a gathering, a group, and therefore more directly engage onlookers as participants.

“Open” has many meanings; we want to engage it as “open-ended,” indeterminate, and also as physically open and as possibly vacant, abandoned, unused. Gabriel Chalfin-Piney and Aida Ramirez’s performance stemmed from their existing collaboration and background in public/open-air theatre. Because it called so much upon the senses, it was somehow intimate despite being in a large open space. This was especially poignant in the context of collective sensorial deprivation required by pandemic restrictions.

Maya Nguen’s sound piece and installation filled the acoustic space of the empty lot between two buildings; an uneasy contribution to the sonic environment of the 4th of July. While not many people actually stopped to listen or ask what we were doing, someone called the police on us complaining about noise—though probably also for the suspicious activity of an odd installation in a vacant lot. This interaction revealed our position in the “public” space for a certain onlooker, and also revealed some of the (political) meanings of that particular open space, a private, albeit empty, property.

CN: I love the title Open Sheds Used for What?, because it is a question that many people ask when they see an object and/or space that they don’t understand. Often the first thing on someone’s mind is “What is it used for?” “What does it do?”. Do you see Open Sheds as an anti-functional piece, or simply embodying a function that challenges what culturally we deem as a valuable function?

CRS: The original phrase, in its indeterminacy, carries possible political, insurgent meanings. I had not thought about the term “function” before; the project is certainly meant to always ask that question: of artists, to decide how to “use” it, and of passersby, who might inquire about the uses of the structure and the surrounding open spaces. In a sense, the first thing the installation does is to make an (open) space visible, to call it into existence; the next is to propose a use, or lack of use, or dysfunctional use. This gesture could be anti-functional in the sense that predetermined functions (or their lack) embody systems of thinking, production, and a valuation that preclude agency and must be questioned. Regarding what the structure may do to open spaces in the city, I certainly hope it can also have the “function” of challenging the systems of value that shape our view of urban/public spaces, and of stimulating imagination about what these spaces can harbor.

MRS: “Open sheds used for what” is taken from a line in Julian D. Smith’s diaries. Julian D. Smith was the director of a US American mine in Peru between the 40s and 60s, and I had read his diaries as a research assistant for Jennifer Scappettone at the University of Chicago.

The title of the project comes exactly from the experience you describe. Encountering an object or structure and not knowing what it’s “for.” Julian D. Smith saw some “open sheds” during a visit to a mine site in Peru, and jotted down in his diary: “Open sheds used for what? Arsenic maybe in barrels.” This line stuck with me because it was so unusual for his writing. He was fastidious, comprehensive; his language indicated knowledge and privileged that where he had precise knowledge. Then he wrote this ungrammatical sentence, unresolved, retaining the very surprise of the encounter (as if he had written it upon seeing the sheds). This sentence contains a potential of subversion, like the “arsenic” that might be in barrels. (Are the barrels in the sheds? Beside them? Not near at all?).

Julian D. Smith was an agent in a process that carried on US American imperialism and environmental depletion in South America, that reinforced the role of Peru as a provider of raw material that was now mined by a foreign company and mined even at low percents of ore due to new open-pit mine technologies implemented there. That, too, was a process of redefining space. How can we think about a process of construction that is not also (so) destructive, that does not deplete more possibilities than it creates? In that sense, too, this might mean moving away from what we’ve so far understood as “functionality.”

The title doubles as a question or proposal for the artists–what to do with this open shed? (This might sound like the project is turned too much inwards to itself, but in fact, asking the artists and making their interventions is as much part of the art project; oriented to process more than to products).

CN: I understand that at least one of the project’s iterations has “ended” in a group dismantling of the piece. Does this happen each time? What can be learned from the physical deconstructing something together?

CRS: For that first stage, Marina and I wanted to experiment with that idea of progressive enclosure I described above. We envisaged an arc of construction that would more or less embody different elements of spacemaking: joining, partitioning, enclosing, and finally dismantling. Dismantling would close the cycle of construction with a collective gesture of taking apart, enabling it to be reused later. We calculated that this destructive gesture could occur on July 4th, a coincidence we embraced as some kind of commentary. Since we were on private property without authorization, and given volatile conditions in the summer, we didn’t know actually how long the project could last; it might have needed to end after that arc, or we might have wanted to and been able to keep it going. In any case, dismantling was not necessarily the end of its life in Bridgeport. But that week–after having the structure moved and thrashed a few times–, the owner of the lot came by and talked to Marina, and they forged an agreement to move the structure by July 5th. The timing was fortuitous, as we were already planning on closing that phase, but we were more or less kicked out of that lot.

Dismantling together, and having that be an event of construction, was important to us; we saw it as a phase in the cycle of transformations (rather than an ending). It was in fact the most truly collective and least authorial of the gestures; there is a certain joy in taking things apart, and the rediscovery of possibility. But it doesn’t happen every time; we didn’t plan an arc for the next locations of the structure. The frame was actually taken apart and [put] together a few times in Pilsen, depending on the needs of the participants, and as we moved it between three lots around the Cullerton and Sangamon intersection. The Pilsen phase (and potentially the entire project) was meant to end at the end of August, as Marina was moving to Germany in September. But then, again fortuitously, Edra Soto approached us at just the right time and asked if she could host Open Sheds in her backyard [at The Franklin]. We moved it there in the first week of September, after Dan Sullivan (her husband and co-founder of the Franklin) made some much needed repairs in his shop. With the structure in a more sanctioned art space, though also domestic and unconventional, we would be able to keep interventions going even after Marina had moved.

MRS: We had this arc that led to a complete enclosure, a negation of openness (you wonder what’s inside but you can’t get in), in this case with ply boards that had a timely relationship to the boarded-up windows across the city; and then dismantling. In the next phase, it was important for us to relinquish our authority to determine or to plan the transformation of the octagonal frame (even as it happens through artists’ works). At one point I compared [this] to a process where an unfair structure has been dismantled, after which perhaps the only way to find a new world (as a society, as a biosphere) would be to iterate, to test, to allow for multiplicity and remember that the way things are is open for change.

CN: What is next for the Open Sheds?

CRS: There will be a few more interventions at the Franklin until December, starting with Graham Livingston, who is returning with a work related to his first installation in Bridgeport. We are currently talking to some three other collaborators, but have not fixed dates yet. Afterward, I am not sure! The future of Open Sheds will announce itself like it did the other two times it moved. It may or may not continue in a different location.

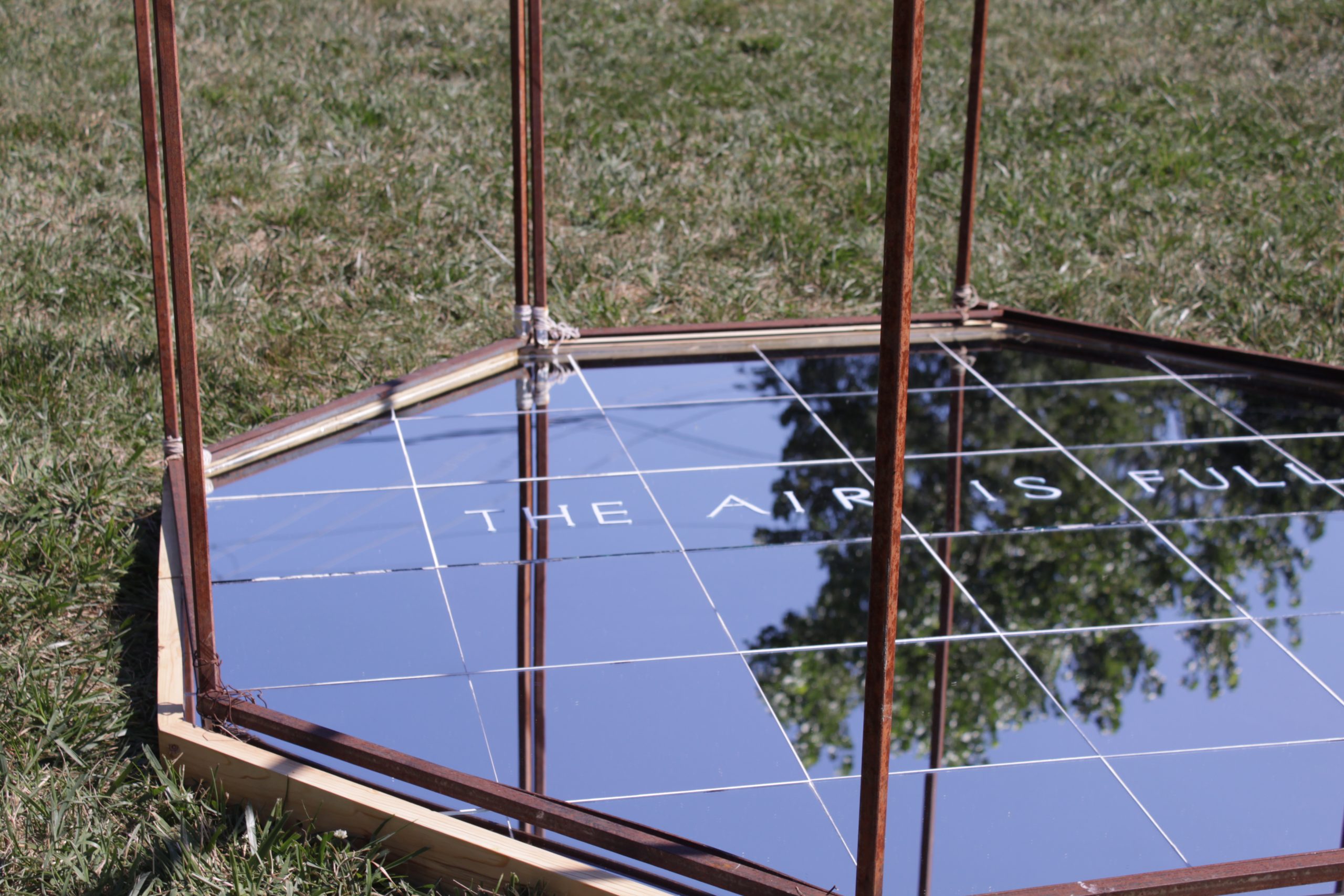

Featured image: “The Air Is” by Gabriel Moreno, installed on August 17, 2020 in East Pilsen. Installation of a mirror platform in an octagon metal frame. This view of the installation shows the words “THE AIR IS FULL”. Photo by Cecilia Resende Santos.

Christina Nafziger is a writer, editor, and curator based in Chicago. Her research focused on performativity within the image and the effect archiving digital images has on memory and identity. Her recent writing investigates the work of artists with research-based practices as well as the role of the archive and its capacity to alter and edit future histories.