The title of the 2022 MFA Thesis Exhibition for the University of Chicago’s Department of Visual Arts is Beautiful Snail, a name that intrigued me as well as struck me as odd, as I found upon visiting no direct connection between the work on view and a snail. I can only assume that any mention of a snail is a reference to slowness—a beautiful slowness that is the process of making art. This is perhaps even more relevant during an MFA program. Time seems to move fast, while the artist as a student pursues the often painstakingly slow process of attempting to create while simultaneously experimenting and challenging their work while they have the space to do it. And so, out of respect for this slowness, I moved through the exhibition Beautiful Snail with patience and quiet listening, deliberately slowing my pace and consumption. (I later found out that the configuration of the gallery space itself is a spiral, a shape that is inherently connected to a snail.)

The 2022 MFA class included Sophia Anthony, Caitlyn Au, Scott Vincent Campbell, Soo Jin Jang, Miles MacClure, Elissa Osterland, Abigail Taubman, and Wilson Yerxa. The work ranged wildly from traditional media and approaches, such as Sophia Anthony’s two-dimensional figurative paintings and Abigail Taubman’s silver gelatin prints, to unpredictable installation work, such as Miles MacClure’s arrangement of multiple screens and video to Soo Jin Jang’s altered version of a corner store display. The juxtaposition of these different approaches was not quite jarring, but kept my attention, drawing me in.

The first space I encountered was a room filled with dozens of pieces of paper with sketches of the body: several eyeballs painted over here, a drawing of the mouth over there, a sketch of a model sitting off to the side. Together, they appeared to be an amalgam of figure studies, a layered way of showing the process and work that happens before the final piece is finished. For Wilson Yerxa, these pieces are in fact the final piece. In this installation, titled Corner, the parts were as important as the sum, as the individual drawings together created a half-dome of tethered together body parts, fleshy in color and graphic by nature. The piece allowed the viewer to enter into Yerxa’s process, an intimate glimpse behind-the-scenes. Collectively, the drawings and paintings formed a compelling installation that encompassed and expanded the space as well as our view of the human body.

Another installation was presented further into the exhibition space and titled: making up people, and other fun activities by Miles MacClure. Comprised of multiple screens with various videos, larger-than-life pine tree car air fresheners, photos of faces, tubes, a bucket filled with a nefarious liquid, and more, the installation formed a constellation of imagery that poked fun at surveillance and influencer culture while simultaneously interrogating the very notion of “Contemporary Art” (capital “C,” capital “A”). Photos of various people’s faces were connected to tubes, making it appear as if they were all “drinking the Kool-Aid” from a nearby slop bucket. Above the sea of faces hung a screen showing rotating clips of different internet celebrities recording Cameos—an Internet service that allows you to hire celebrities to deliver a personalized message from $10 to $500, depending on celebrity status. These Cameo segments typically include messages like, “Happy Birthday!” Or “Congratulations!,” but these messages said something altogether different. They all said, “This is so contemporary, contemporary, contemporary…”—an uncanny message that vibrated throughout the exhibition, echoing words similar to artist Tino Seghal’s humorous and participatory performance piece This is so Contemporary. What does “contemporary” mean, anyway? The word loses all meaning in the repetition and left me wondering if the word ever held any concrete meaning at all. The piece, as a whole, demands attention, with moving images and sound on a loop, but doesn’t take itself too seriously. Instead, it playfully and boldly questions the very model and institutional structure in which it was created in: the MFA program.

Across from MacClure, Scott Vincent Campbell’s pieces were on display together, but were vastly different from one another, displaying a breadth of understanding of medium and subject. Sitting adjacent to one another, Campbell’s pieces I didn’t think you’d be like that (Mold 1) and (Mold 2) were unmistakable standouts of the show. Although contrasting in colors (one utilizing mostly neutrals and blacks while the other contained a striking red), both pieces were part sculpture and part installation, complete with a light source inside. In (Mold 1), a wooden structure sat on a large mound of a substance that looked eerily similar to gunpowder. In (Mold 2), the wooden structure sat on what appeared to be red faux fur. In both, the light and texture were striking; the black powder inched towards the viewer, the red fur crawled across the gallery floor and wall. It caused me to back away while also leaning closer to inspect the dynamic pieces in a deeper way. In (Mold 2), black hand prints could be seen on the sides of the wooden structure in the installation—an echo of the black powder in (Mold 1). Although these two pieces don’t physically touch, they seemed to interact with each other, reaching toward one another—sisters but not twins. Here, the material is essential and form is central, creating lush texture through attention to detail. Together, the two form a dialogue across the gallery that the viewer must walk to and through in order to enter the next space, the final area of the snail.

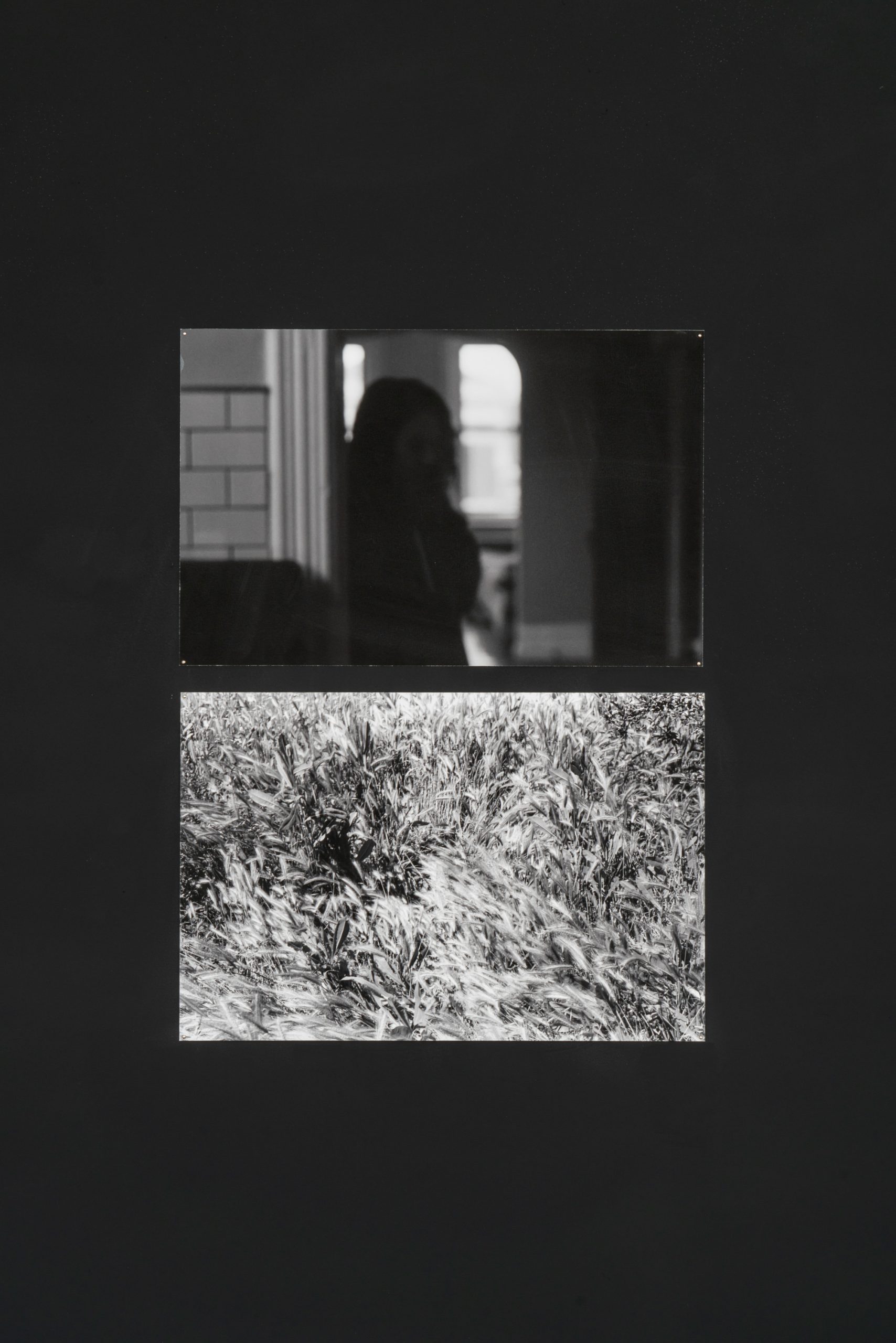

The last space I walked through was perhaps the most unified, displaying a perfectly paired duo of artists: Abigail Taubman and Elissa Osterland. This specific selection of works by the artists was so in sync with one another, so akin, that they almost felt like their own separate, curated show. A strong thread could be seen and felt between the works, as all of the pieces contained the same palette (black and white) and the same soft tone (tender and ethereal).

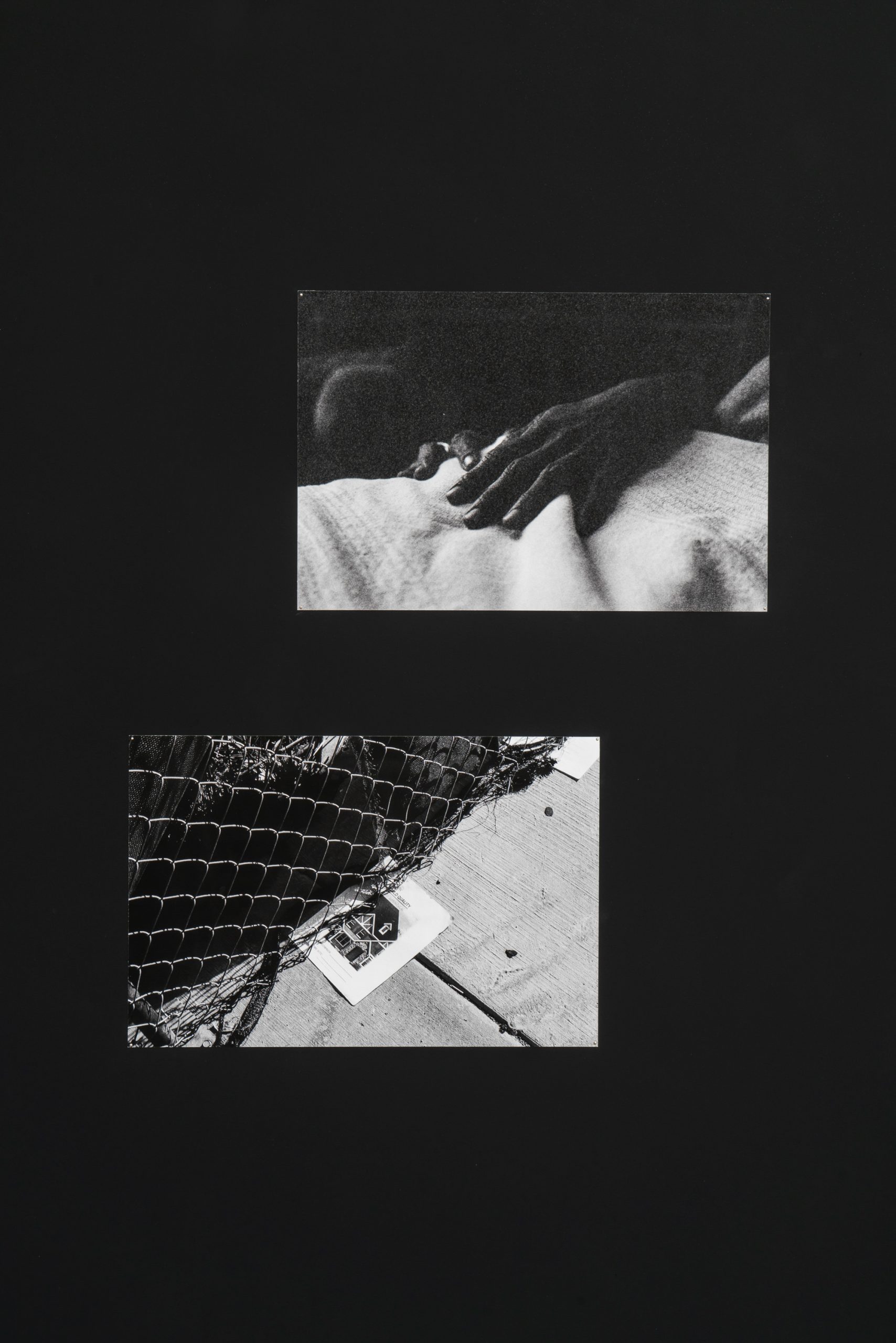

Taubman’s gelatin silver prints form abstracted fragments through folds, while her photographs directly across revealed images that are like fragments of a memory. These images were gracefully installed across a black wall, a constellation of moments that hold nostalgia and beauty. Walking seemed to be a key element in the artist’s practice, her imagery stemmed from photos taken on walks—imprints of a path taken, an action. Contrasting this dark wall was Elissa Osterland’s monumental piece Giant Slide. Created with graphite, charcoal, and ink on paper, this piece contained fragments of imagery, but on white instead of black—an inverted reflection of Taubman’s adjacent display. In the piece, the imagery was transferred through charcoal rubbings, which also caused part of Osterland’s own body to leave marks across the surface—an imprint of the body of movement. Directly across from Giant Slide were Osterland’s own gelatin silver prints, completing this four-sided pattern of black and white images, and forming a delicate grouping that compelled a slowing down to investigate these shards of imagery. Although the two artist’s images came from very different places, they functioned as breadcrumbs, imprints of a body or action, scraps of evidence of a moment in time, fragmented and scattered for us to gather.

Slowness is not natural for me. In many ways, working slowly and consuming slowly goes against the grain. It works directly against what most of us have been taught. The pressure to produce can be impossible to resist, especially as an artist completing your MFA at UChicago. However fast or slow these pieces were created, together, they formed a contrast that encouraged me to take another look, slow down, and pay attention. Both with the arrangement of artworks—spiraling like a snail—and the content produced, the exhibition pulled me in and pushed me out. Beautiful Snail was a refreshing combination of works that gave me something familiar to hold onto while simultaneously throwing me for a loop, always keeping me on my toes.

Beautiful Snail was on view from May 6 through June 12, 2022 at the Logan Center for the Arts in Hyde Park.

Christina Nafziger is an art critic, editor, and writer based in Chicago (occupied land of Ohklahomo, Potawatomi, Ojibwe, and Odawa people). Earning an M.A. in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths University of London, her research focuses on the effect photo collections and archiving have on memory and identity and the potential capacity these collections have in altering and editing future histories. Working with a collaborative approach to her editorial work, her writing investigates the work of artists with research-based practices and how they engage with archives.