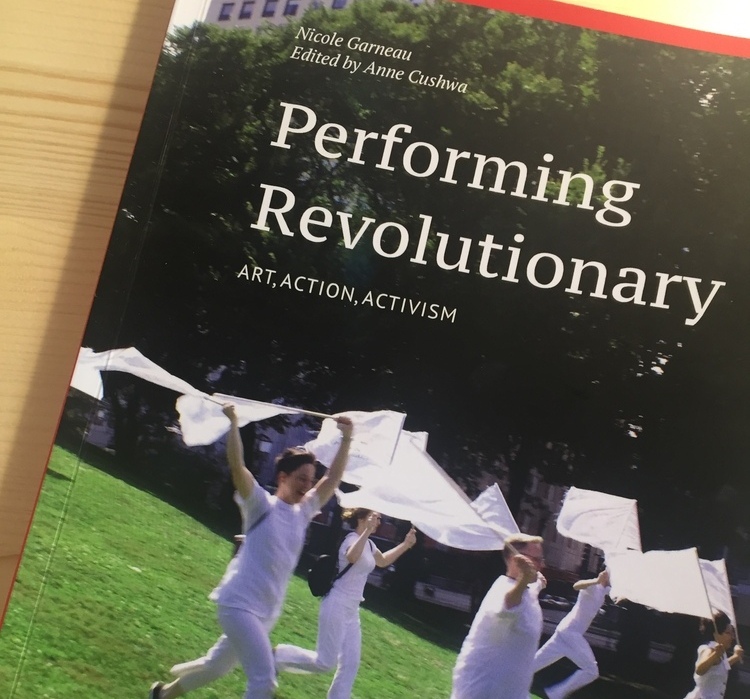

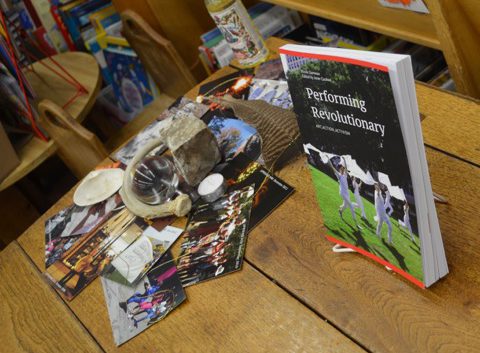

Artist and activist Nicole Garneau’s new book Performing Revolutionary: Art, Action, Activism takes you on an intimate journey through her project UPRISING, a series of performances that took place once a month for five years. Defining her UPRISINGs as “public demonstration of revolutionary practices,” these performances, protests, celebrations envelop around efforts of connection, community, and care in a way that is reflected in the writings in this book (Garneau, 2). The artist lovingly holds your hand while she walks you through how this project began, and then onwards into each of the 60 performances taking place in eight states and other international locations, beginning in 2008. Each of the sixty performances explored within this book is two-fold: one part being ‘IN ACTION’ which describes the performance and event; the other being ‘Revolutionary Practice,’ which offers a prompt, an exercise the reader can do themselves, putting the action into practice. Garneau describes this book as, “The result of many years of exploration into how performance can be used to create public demonstrations of the possibilities for a more loving, just, and humane present and future” (Garneau, 2).

With an opening sentence of “It begins in Chicago,” the city becomes the backdrop and stage for UPRISINGs beginnings. Growing up in a suburb of Chicago and having attending UIC and Columbia College, the artist explains,

“Chicago was my creative and activist home for more than 20 years. Chicago offers endless variation as a performance site and as a long-time Chicagoan I felt entitled to explore the city and its spaces in this way. Making performances in the streets or at Chicago events was a way of expanding my social and activist communities, of participating actively in the city.”

Garneau, who has been involved in theater ultimately her whole life, has been involved in various Chicago organizations such as Women’s Action Coalition, Queer White Allies Against Racism, AREA: Chicago Arts, and Sissy Butch Brothers’ Gurlesque Burlesque, just to name a few. In the introduction of Performing Revolutionary, Garneau discusses her involvement in Insight Arts in Chicago, whose dedication to cultural work and social change heavily influenced her practice.

This book is as static as the UPRISING project itself, which is to say that it is absolutely not. Like the project it holds, illustrates, and explores in its contents, this book is a living series of events. It is an action that is happening still. And yes, each UPRISING performance embodied the activeness of this term. Although these performances did ‘happen’ in the past tense, UPRISING in the form of a book cannot help but spur something new once read. It is at once a documentation and a nudge, a push for the reader. It is a compelling; a manifesto in the sense that it declares the intention of each UPRISING action. In a way, each performance is a declaring in itself. What was happening in this project continues as a constant hum; this hum, these happenings, are transformed with the words of this book into a compulsion – a buzzing that is being drawn out with each telling of an UPRISING, each instructional ‘how-to’ accompanying each action. Although, Nicole Garneau says she prefers the, perhaps more accurate, term “cultural work” for her practice, a number of words have been thrown into this ambitious project, such as ‘ritual’ or ‘intervention’ (Garneau, 5). What has become my personal favorite term for these UPRISINGs is ‘ceremonies’ due to not only the intimate solidarity and air of communion present in the work, but also the thickness of love and openness that could not be ignored at her book talk on April 20th at Women and Children First Bookstore in Andersonville, Chicago.

As I walked into the space of the talk, it was filled with an energy and excitement that could only be described as both a homecoming celebration and an anticipation of something historical. As a way of ‘activating’ the space, not-so-optional introductions were done around the room, pleasantly compelling audience participation. Along with our own names, each person was invited by the artist to speak a name of a revolutionary woman. Names like Katherine Graham, Sojourner Truth, Laverne Cox, and Maggie Nelson were uttered out loud, entering the space, and blown towards the front of the room where a collaborative altar stood to honor revolutionary women and trans-people. The reason I felt this sense of homecoming – this palpable joy of return – was because of how many people in the audience were personally involved in many of Garneau’s past performances as well as UPRISING. Many had been a part of her work, and more specifically, many had participated in UPRISING #10, which took place ten years prior at the same bookstore, where participants created the original alter which we honored that night. I was surprised to find that this familiarity did not cause me to feel excluded, but thanks to an eager openness from others did I find myself becoming a part of this event in its past, present, and future forms. I asked Garneau about her connections to the members of the audience:

“I knew a lot of people in that room. There were a lot of folks there that were involved in feminist activism and other kinds of radical art projects over a couple of decades in Chicago. There were also a lot of people I didn’t know—but I met them that night, because I think that in a space like that, it is important for us to meet each other. I want to hear people say their names, and name revolutionary women and trans people, and activate an altar. I like for the first activity to be something interactive because everyone in the room ‘checks in’ to the space in a more active way. Practicing being more revolutionary people includes being radically present with each other.”

Garneau’s attitude and intentions within the talk not only activated the audience, but also activated her book, transferring her UPRISINGs from ‘have happened’ to ‘happening.’ Reading passages outloud initiated the words into the realm of oral history, passing them to us, giving us these moments in which compassion and social justice were being declared. One of the UPRISINGs Garneau discussed at the talk that will live especially in my mind is UPRISING #46, which took place in Grant Park, during an Occupy Chicago march in 2011. Marching in this demonstration, Garneau held up giant paper signs with lyrics for songs like “I Will Survive” written on each, inviting others in communal song. In the event’s description, Garneau states, “As police moved in on the Occupy encampment and loaded 130 people into wagons, we did not even need lyrics. I started singing ‘This Little Light of Mine,’ and the crowd around me joined right in” (Garneau, 138). The simple, shared joy of singing together seemed to hold such power in that moment. Singing out loud and coming together—speaking out loud and listening together—ignites a kind of supported hope that can often be difficult to feel without the presence of others, particularly during the times we find ourselves in. This is what is held in each UPRISING performance: a notion that something can be done, things can be changed. This importance of this invaluable, as it is an all-too-often fleeting feeling.

Garneau states, “To create positive change, we must discover fresh perspectives on moving from critique to possibility, maintaining hope in light of the numbing negativity of contemporary political discourse” (Garneau, 14). This possibility, this maintaining of hope, is a practice within itself, enacted in each performance in UPRISING, but also activated and practiced within the reading of the words in Performing Revolutionary: Art, Action, Activism.

Featured Image: Image shows artist and activist Nicole Garneau at her book talk standing in front of a wall of children’s books. She is dressed in all white with a shirt that reads “UPRISING.” An audience member is also standing, talking to the speaker. Photo by Uncle Bear Klein, courtesy of Nicole Garneau.

Christina Nafziger is a freelance writer with a background working in curation, arts administration, and community outreach. Originally from Indianapolis, she recently earned an M.A. in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths University of London. Her area of research focuses on gender studies, performativity, virtual identity, and cyborg culture.

Christina Nafziger is a freelance writer with a background working in curation, arts administration, and community outreach. Originally from Indianapolis, she recently earned an M.A. in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths University of London. Her area of research focuses on gender studies, performativity, virtual identity, and cyborg culture.