It goes without saying that so much of the labor in an artist’s practice goes unseen, ranging from the countless hours of trial and error experimenting with a medium before getting it right, to the often mind-numbing planning and prep work when starting a new piece. However, there is yet another layer below the surface of this complex production that is inherent to the creative process: research. There is a collection of information, images, and archives that happens even before any pen is put to paper, feeding and informing an artist’s body of work. Works Cited asks artists to uncover this part of their practice with us, sharing research materials such as essays, playlists, online archives, and tips on how to navigate them. In the spirit of open access, this column also serves as a resource in and of itself, as each interview includes access to these materials in the form of either reading lists or sharable links.

For this edition, I spoke with artist Barbara Diener about her most recent project The Rocket’s Red Glare. Here, she turns her critical lens onto the life of rocket scientists Wernher von Braun and Jack Parsons, whose stories weave in and out of questionable judgement, swaying back and forth between monumental and scientific breakthroughs, and complicated interests and alliances. A selection of images that focus on Wernher von Braun are currently on view at the DANK Haus German American Cultural Center. Through the exhibit, Diener carefully presents us with photographs that reveal the remnants of history that acknowledge and preserve what von Braun had achieved for NASA, but also the fragments of history that slip through the cracks––the crumbs left behind in archives and within the town of Huntsville, Alabama (home of Space Camp) itself.

As if a detective were following clues, Diener invites us down the rabbit hole with her as she uncovers obscure archival materials like journals and photographs, and melds them within her own photographic practice,sometimes quite literally, as she physically fuses together photos found in von Braun’s archive with her own photographs. The result is a challenging and stunning series of images that tell a story of a rocket scientist who once worked for Nazi Germany, and whose past was disregarded by the U.S. government for the sake of scientific progress and ambition. The Rocket’s Red Glare poses questions like, “Is science neutral?” and “Who controls how history is written?” as Diener photographically investigates how history is kept, stored, learned, and told.

Reading/Listening List:

- Conspiracy Theories Podcast

- Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War, Michael Neufeld, 2007

- Dark Side of the Moon: Wernher von Braun, the Third Reich, and the Space Race, Wayne Biddle, 2009

- Operation Paperclip: The Secret Intelligence Program that Brought Nazi Scientists to America, Annie Jacobson, 2015

- Strange Angel: The Otherworldly Life of Rocket Scientist John Whiteside Parsons, George Pendle, 2006

- Unexplained, Season 3, Episode 1, We Are the Witchcraft.

Christina Nafziger: Can you tell me a bit about your most recent project, The Rocket’s Red Glare? A selection of works from the series is currently on view at the DANK Haus. What is the focus of this particular exhibition in relation to the larger project?

Barbara Diener: The Rocket’s Red Glare follows in the footsteps of two instrumental rocket scientists. Teenagers in the 1920s, a time in which rocket science and space exploration were confined to science fiction novels, Wernher von Braun in Germany and Jack Parsons in Pasadena, CA were part of their respective rocket clubs. They talked on the phone for hours about their home-grown explosions and rocket fuel tests. One went on to develop the V2 rocket for Hitler and the Saturn V for NASA. The other made groundbreaking contributions to the development of rocket fuel but was also second in command of Aleister Crowley’s occult religion, Ordo Templi Orientis, and was written out of NASA’s history for decades.

In 1932 Wernher von Braun went to work for the German army, which fell under National Socialist rule the following year. Accounts of when he joined the Nazi party vary, but by 1937 he was the technical director of the Army Rocket Center in Peenemünde, a small coastal development in Northern Germany where the V2 rocket (Vengeance Weapon 2) was created and tested. This location has now been turned into an educational facility, cultural events space, and history museum—the Historical Technical Museum, Peenemünde. After the war, when von Braun was brought to the U.S. under the controversial Operation Paperclip, a government initiative to secure and extract German scientists, his talents were called upon by the U.S. military. He settled in Huntsville, AL with members of his original rocket team where they eventually developed the Saturn V and put the first man on the moon.

BD: Jack Parsons was born and raised on Orange Grove Boulevard, also known as Millionaire’s Row, in Pasadena, CA. Although he never attended CalTech, he spearheaded the self-proclaimed “Suicide Squad,” a group of CalTech students who shared Parsons love for rocketry. In 1936, these founders of what would become the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) conducted the first rocket tests in the Arroyo Seco, and were soon after commissioned by the U.S. Army Air Corps to develop “jet-assisted take-off” rockets. In subsequent years Parsons became more and more involved with the Los Angeles chapter of the Ordo Templi Orientis and he opened up his home, the Parsonage, to an eclectic cast of characters. In 1942, Parsons co-founded the rocket and missile manufacturer Aerojet, but by 1944 he was bought out and his affiliations with military and government projects were terminated. Parsons died tragically from fatal injuries after a presumed accidental explosion in his home laboratory.

To weave together a sense of these two complicated stories, I have photographed places of significance, made portraits referencing existing images, and appropriated archival material. For the exhibition at the DANK Haus I focused on Wernher von Braun’s part of the story.

CN: What got you interested in the life of Werner von Braun and his complicated, problematic past? What led you to discover who he was and his past ties to Nazi Germany?

BD: I grew up in Germany; my father was German and my mother is American. She still lives in the house I grew up in, but my dad passed away 13 years ago. All through high school I had wanted to leave the small town I grew up in, so I moved to Seattle (because of Nirvana) after graduating. The more distance I had from this rural area I was raised in, the more I started to appreciate it. Once my father died, I felt a renewed kinship with my German heritage and embarked on my own conflicted journey to reckon with Germany’s past.

My father was a young boy during WWII, so the stories I grew up with were accounts of civilians trying to survive. It was always hard for him to talk about any details regarding the war, and therefore hard for me to know exactly where my family fit into that historical moment. As far as I know, my grandfather and uncle did not actually join the Nazi party but both fought on the German side. My uncle was wounded at the very end of the war and died of his injuries. He had just turned 18.

Wernher von Braun’s story—growing up in Germany during the 1920s as National Socialism was on the rise, then working for the Nazis to develop a missile that bombed civilians, and lastly being celebrated as the architect of the rocket who landed a man on the moon—truly exemplifies the multifaceted, complex narrative I am trying to unpack with The Rocket’s Red Glare.

CN: As you yourself are German-American and grew up in Germany, how did you feel the more you found out about von Braun’s work with the Nazis, as well as his work with NASA in the U.S.? How has this experience shaped or changed the way you view American history or history in general? In learning about Operation Paperclip, do you feel that certain unethical decisions are made, or histories ignored, for the sake of ‘progress’?

BD: Yes, absolutely! It is nothing new to approach history, and the way it has been disseminated, as something malleable rather than fixed. We finally consider the voices of minorities and underrepresented communities (current state of this country aside) and are able to have a much richer and more nuanced understanding of historical events. But as we know, for centuries, history has been told by “the victor.” It is scary and intriguing to me, but not surprising, that the U.S. government was willing to, even intent on, sweep von Braun’s past under the rug in order to use him as a poster boy and success story for Operation Paperclip.

CN: Let’s talk about your work in the archive. What was your experience working within archives to learn about von Braun’s life? Did you have any trouble with access?

BD: Historically, the archive as a concept has been viewed as a place that contains facts. Similarly, photography was erroneously considered a medium that captures truth, so it is fitting to bring the two together and question how information is disseminated to the public and, ultimately, how history is written.

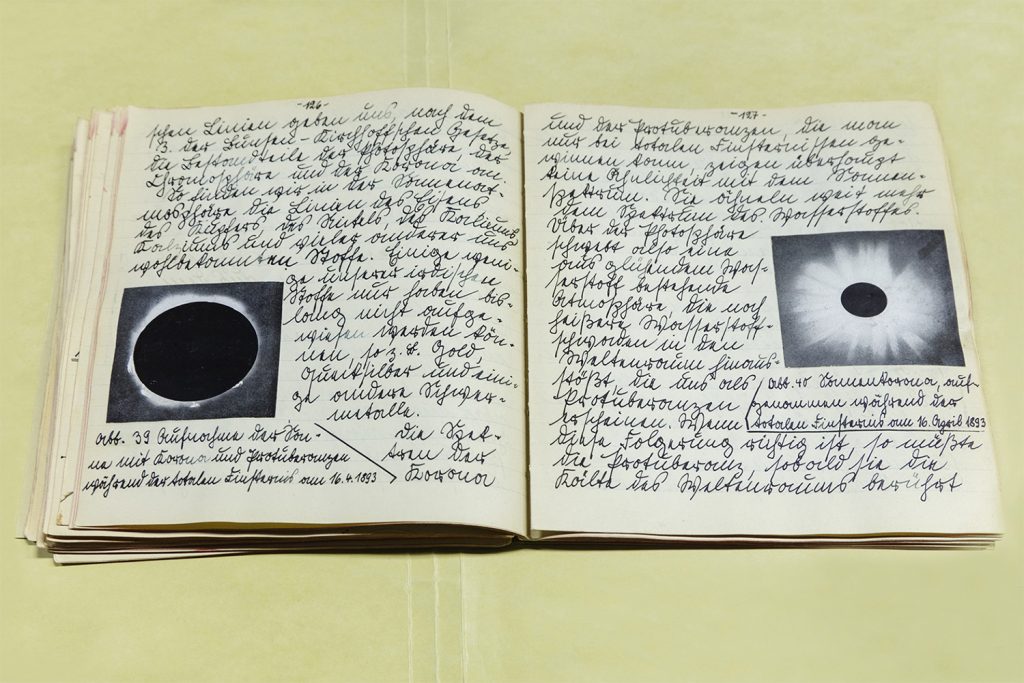

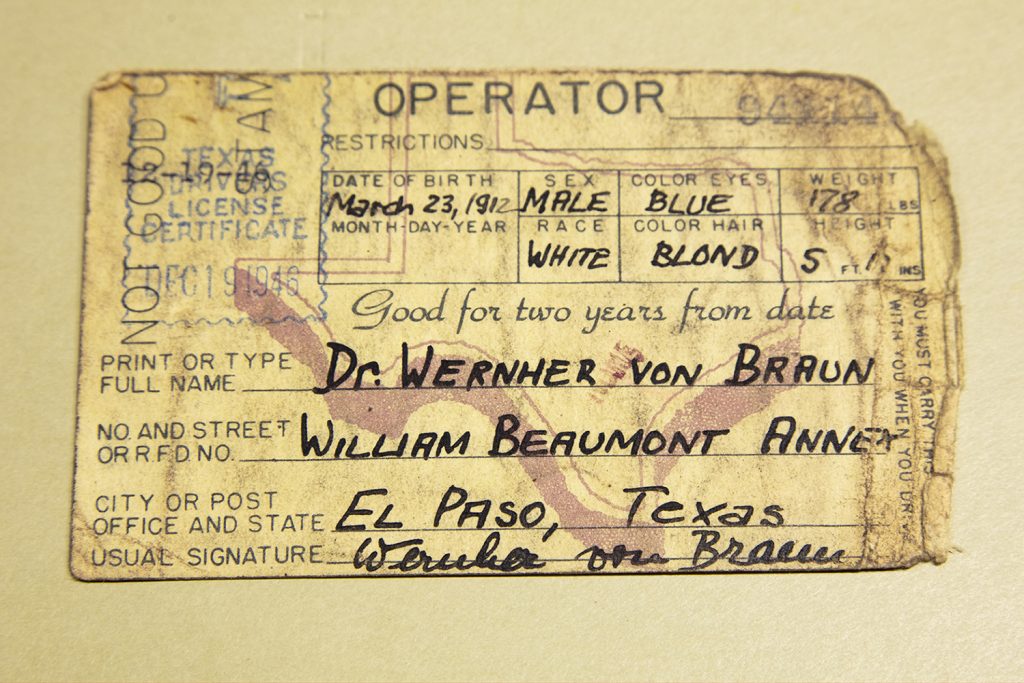

Shortly after the moon landing Wernher von Braun was instrumental in founding the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, AL, an educational facility that still today hosts Space Camp. There, the Wernher von Braun Archive was established, which houses ephemera and historical photographs that von Braun brought over from Germany, including his high school math notebooks, a manuscript for an astronomy book he wrote at age 15, handwritten drafts for speeches, driver’s license etc. In addition to their historical relevance, this ephemera also helped me tell von Braun’s story.

Coming across imagery of swastikas has a nauseating, repulsive effect on me. It is still jarring symbolism for me since swastikas are illegal in Germany. So, when I found the prints that I re-photographed for Funeral for Victims of Air Raid, Peenemünde, Germany and Nazi May Day Celebration, it seemed important and poignant to include them. I was trying to figure out how to address the overt link to Nazism and finding these photographs felt like a way to do that.

The time I got to spend in the Wernher von Braun Archive was absolutely exceptional. Even though there have been many books written about von Braun and Operation Paperclip, this specific archive felt like an untapped resource. Some of the photographs I encountered there were just too extraordinary to keep stored away in a box.

CN: What inspired you to make the decision to document and photograph the physical materials of the archives itself and incorporate it into your series? Can you speak a bit to these photos, such as your image of von Braun’s journal, or the image of stacks within an archive?

BD: My interest in the archive is two-fold—in the information it holds and in the place and materials themselves. Several books have been written about Operation Paperclip, von Braun, the Space Race, etc., so it was never my goal to merely discover or uncover facts. I wanted to photograph the archive as a physical space and von Braun’s personal ephemera as objects.

Re-photographing some of these archival materials from his teenage years, especially the astronomy manuscript which he wrote at age 15, adds a layer to his story that, given his ties to the Nazi party, might seem difficult to acknowledge—at his core was a boy who wanted to go to space.

At this point it should be said that von Braun’s V2 rockets, which were used to bomb London, were built by slave labor in the Dora-Mittelbau concentration camp. There is no way he did not know this.

CN: Much of the photographs in The Rocket’s Red Glare were taken at different sites, many of them around Huntsville, Alabama. Where did you travel and why? Were you able to travel to your subject’s home or meet any of his family? If so, how did they feel about von Braun’s past?

BD: Since Huntsville became such a crucial site for von Braun and his rocketeers, most of my photographs pertaining to that part of the project were made there.

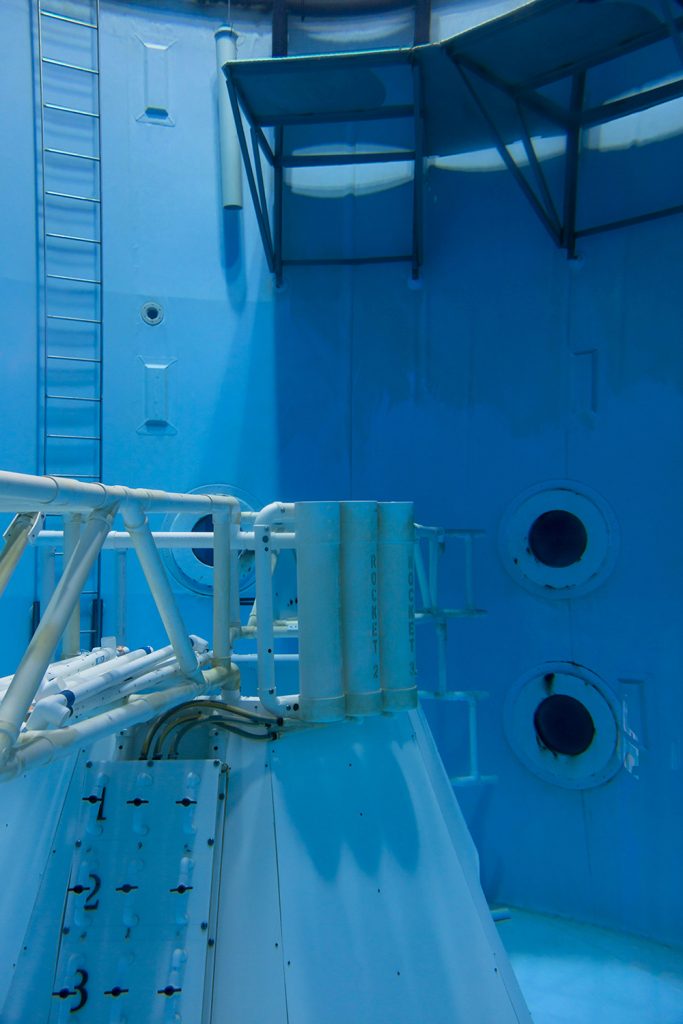

I traveled to Pasadena to explore the neighborhood Jack Parsons grew up in, visited the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and photographed in the Arroyo Seco, the site of Parson’s first official rocket fuel tests in 1936.

Von Braun’s family no longer lives in Huntsville but I was able to meet up with children of some of the other scientists and engineers who worked with von Braun in Peenemünde and later in Huntsville. Their stories are all fascinating and to simplify and sum them up a little for the purpose of this interview, they experienced variations of the following: A young scientist, with a wife and small children, is sent to the Eastern Front and wounded. Upon his return home, the entire family is sent to Peenemünde, so the husband can work with von Braun. I got the sense that they felt as though their families’ stories had not been given the same attention as Wernher von Braun. Their fathers’ names are lesser known even though their knowledge was crucial in many regards.

One major part of this project is, however, still missing: I absolutely have to travel to and photograph in Peenemünde, spend time in the archive there, and absorb the atmosphere. I imagine it is quite eerie and bucolic at the same time. As soon as there is a COVID-19 vaccine, I will be on an airplane to Germany!

CN: I understand that you were still in the process of creating work for this project when COVID-19 became a national crisis. How did this affect your practice? Since much of the work involved traveling to certain historical sites, how was your work forced to pivot to accommodate the quarantine and travel bans?

BD: I was supposed to travel to Peenemünde in April of this year to photograph there and conduct research in the archives. Of course, I had to cancel that trip. In early March it still seemed possible to travel within the States, so I wanted to instead spend a few additional days in Huntsville, AL at the U.S. Space and Rocket Center. Unfortunately, this latter trip was not possible either.

The trip to Peenemünde was going to yield additional work to include in the exhibition at the DANK Haus but, since I could not go in person, I took hundreds of screenshots of the live webcam that is pointed at the Historical Technical Museum in Peenemünde. From those I created a large collage consisting of 480 small prints of these screenshots, measuring 90 by 80 inches. Sourcing images online and working in collage have both been new elements to my practice that I would like to employ further moving forward.

My exhibition at the DANK Haus also includes a sculptural element, which again is new to my practice, but something I very much enjoyed and would like to continue. I hand-sewed 48 sandbags: plastic sandbags filled with sand and covered in black latex. They were inspired by the repeated imagery I came across in the archive, depicting sandbags used in rocket fuel tests, black latex gloves used in chemical experiments, and black leather prevalent in Nazi uniforms.

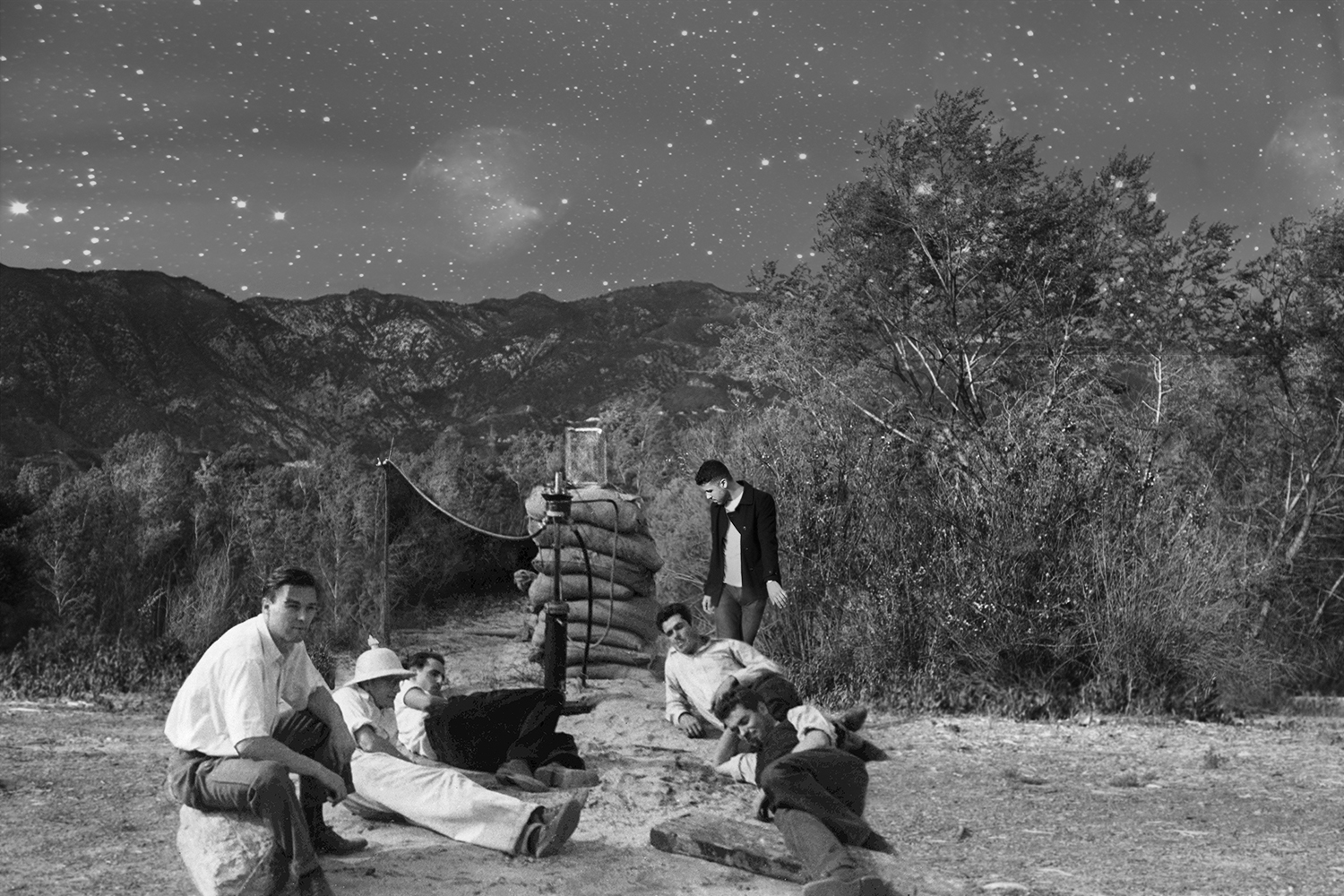

CN: In this series, you bring together the past and the present in an incredible way by photographing archival material and present-day historical sites and replicas. In some instances, you literally fuse together points in time by combining a historical photograph with your own contemporary photography, such as your piece “Suicide Squad,” Arroyo Seco, Pasadena, CA, 1936/2019. How did you create these images?

BD: As part of my research I spent a lot of time sifting through historical photographs in both the Wernher von Braun Archive in Huntsville, AL and JPL in Pasadena, CA. Some were just such great photos that I instantly knew I wanted to use them in some way. Incorporating historical images into my project also opened up the conversation of photography’s role in depicting and disseminating the truth and in-turn passing along historical facts.

To create some of the works for The Rocket’s Red Glare, I re-photographed and scanned some of these photos and documents, as well as superimposed archival images found in both archives with my own photographs. With these pieces I am literally merging time and place.

In “Suicide Squad,” Arroyo Seco, Pasadena, CA, 1936/2019 I have composited a photo of the “Suicide Squad” (Rudolph Schott, Arno Smith, Frank Medina, Ed Forman, and Jack Parsons) into an environmental portrait/landscape of an actor that I took in 2019. I found the actor through Craigslist and was specifically looking for someone who has attributes reminiscent of Jack Parsons—dark hair, a certain haircut and build, etc. The original photograph was taken during the first rocket fuel tests in 1936 in the Arroyo Seco and the photograph I made is in the same location. The first year, “1936,” refers to the date in which the historical photo was made and “2019” refers to the year I took my image and created the composite.

BD: The historical photograph used in Holding Missile, Peenemünde, 1940/2019 is one of the images I came across in the Wernher von Braun Archive, in a box labeled Peenemünde, and when I saw it I knew I had to incorporate into my work somehow. I made the landscape in the background near Mount Wilson Observatory in the hills above Pasadena, CA. This was the first composite for The Rocket’s Red Glare and it is not only combining the past and the present but also Germany and California.

CN: How much research would you say went into this project? Is it ongoing?

BD: Since the project is steeped in and guided by historical facts, as malleable as they may be looking back at the past, research was a crucial component to the work. I spent many hours in the archives of both the U.S. Space and Rocket Center and JPL, looking through documents and photos, reading FBI files and books on both subjects and listening to many podcasts.

I won’t consider the project complete until I have had a chance to go to Peenemünde.

CN: What archives/sources have been helpful to you when researching your subjects and/or finding physical source material? Are there any specific texts/essays/books that were really influential for you? What would be a good entry point for someone who is interested in learning more about this topic?

BD: The podcast Conspiracy Theories has a two-part episode on Operation Paperclip, which is a great entry point for Wernher von Braun. I can also highly recommend visiting The U.S. Space and Rocket Center and the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, AL, once the latter allows for visitors again and travel restrictions have been lifted.

A great entry into Jack Parsons’ story is an episode of Unexplained, Season 3, Episode 1, We Are the Witchcraft. I absolutely loved spending time in Pasadena for this project and can’t wait to go back. Fingers crossed it will be possible again some day to visit and tour JPL. It is really awesome!

CN: The Rocket’s Red Glare weaves together points in time and place, visualizing a story and history that is troubling and multi-layered—a narrative that requires multiple points of view. What do you hope is the takeaway from this body of work? What questions and/or answers do you want to suggest to your viewers?

BD: Rather than presenting a complete view of this complex part of German-American history—classified for decades—I am posing questions about the way that history is passed on through generations, and how facts are distorted, embellished or undermined. Especially in the current socio-political climate, I am asking my viewers to question their news and media sources and demand that the voices of minorities, people of color, and the underrepresented are heard.

Featured image: “Suicide Squad,” Arroyo Seco, Pasadena, CA, 1936/2019 by Barbara Diener. The image is a black and white photograph created from a composite of two photographs, one from 1936 and the other from 2019. A group of men sit in a desert landscape in Pasadena, CA.

Christina Nafziger is a writer, editor, and curator based in Chicago. Her research focused on performativity within the image and the effect archiving digital images has on memory and identity. Her recent writing investigates the work of artists with research-based practices as well as the role of the archive and its capacity to alter and edit future histories.