It goes without saying that so much of the labor in an artist’s practice goes unseen, ranging from the countless hours of trial and error experimenting with a medium before getting it right, to the often mind-numbing planning and prep work when starting a new piece. However, there is yet another layer below the surface of this complex production that is inherent to the creative process: research. There is a collection of information, images, and archives that happens even before any pen is put to paper, feeding and informing an artist’s body of work. Works Cited asks artists to uncover this part of their practice with us, sharing research materials such as essays, playlists, online archives, and tips on how to navigate them. In the spirit of open access, this column also serves as a resource in and of itself, as each interview includes access to these materials in the form of either reading lists or sharable links.

In this edition, I spoke with Selva Aparicio, whose interdisciplinary work examines life, death, and mourning through the use of ethically sourced dead and/or decaying materials. Selva delicately and mindfully strings together elements of the natural world (sometimes quite literally, like in the case of her piece Velo de Luto (Mourning Veil), where she sews together wings of cicadas with women’s hair) to bring our attention to a subject that deeply impacts us all, but one that is taboo and often ignored: the cycle of life and death.

Originally from Barcelona, Spain, she is currently artist-in-residence at the International Museum of Surgical Science in Chicago, where she has been working within their archives conducting research and reflecting on her own experiences involving death. We discuss her early memories that have drawn her to this subject matter, how she finds her materials, and how research and memory often meld together to internally and subconsciously inform an artist’s practice and process.

Reading List:

- “The Performative Corpse” by Bethany Tabor

- Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

- Video: Mourning the Afternoon of 17 August 2017 by Selva Aparicio

- Song: “Anga Pah” by Varua

- The Time of the Doves by Mercè Rodoreda

- On Grief & Grieving by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, M.D & David Kessler

- The Oval Portrait by Edgar Allan Poe

Christina Nafziger: Let’s begin with a general overview of your practice, which often centers on the lifecycle and death of living things as well as rituals of mourning. How did you become interested in this subject and when did it manifest itself in the form of art making?

Selva Apiricio: I grew up in a boat shaped house in the middle of the Serra de Collserola Natural Park, Spain. I had a transient childhood that mirrored my home’s design; I was raised by proto hippies, who named me Selva (Jungle). Like my namesake, I was immersed in the natural world where hand-made objects and animals filled my day-to-day life. I transferred schools seven times and travelers faded in and out of my childhood. There was a group of Rapa Nui [people indigenous to Easter Island] who were a musical group called Varua that stayed with us for a while. One of the musicians, Tito Hotu, was also a sculptor and taught me how to stone carve for the first time. They released an album after their stay and dedicated a song to us: Anga Pahi.

Amidst the often-tumultuous nature of my household, I absorbed a deep sense of calm from my natural environment and began to craft my own sense of liberation through my artwork. The resourcefulness and process of gathering resources that I found around me as a child would carry through as an integral element of my artwork as an adult.

During my pre-teens, my best friend drowned on the Ebro River, it took several days for the body to be found. It was a really tragic death—he was only 15 years old. I was out of town at that time and it wasn’t until after his burial that I was able to return. Those who had seen him told me about what had become of his body after days in the river. Images of his decomposed body were permanently etched in my memories; I kept seeing his empty eyes eaten by the fish. From this point on the concept of “mourning” became key in the making of my work and working directly with dead human donors was an immediate necessity to the understanding of absence and the intricacies of death.

CN: What brought you to Chicago? Did you study sculpture at the School of the Art Institute or at Yale?

SA: I take my commitments seriously. During my last years in Spain, I promised my dog that I wouldn’t leave her side until after she died. When she passed away in 2011, I left Spain and moved to Vancouver, Canada where I worked as a stone carver and learned English. While I was there, I made a close friend that encouraged me to transfer to an American school. I applied and accepted an offer from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, who awarded me a portfolio scholarship. In my last semester at SAIC, I was hit by a pickup truck while crossing a main street in downtown Chicago—Michigan Avenue. It was a stressful time. I was applying to grad school, had two jobs at school, and was finishing my last credits. I had to get hip surgery back in Spain and later came back [to the U.S.] to start my graduate program in Sculpture at Yale University, where I completed my MFA.

CN: I’m really interested in your piece Mourning the Afternoon of 17 August 2017 because of its participatory nature. Because death can be seen as taboo and is often a topic people try to avoid, how did the community react to this piece? Do you feel art has a potential to have a healing quality? If so, do you think this potential is different when someone participates in the art making rather than viewing the finished piece?

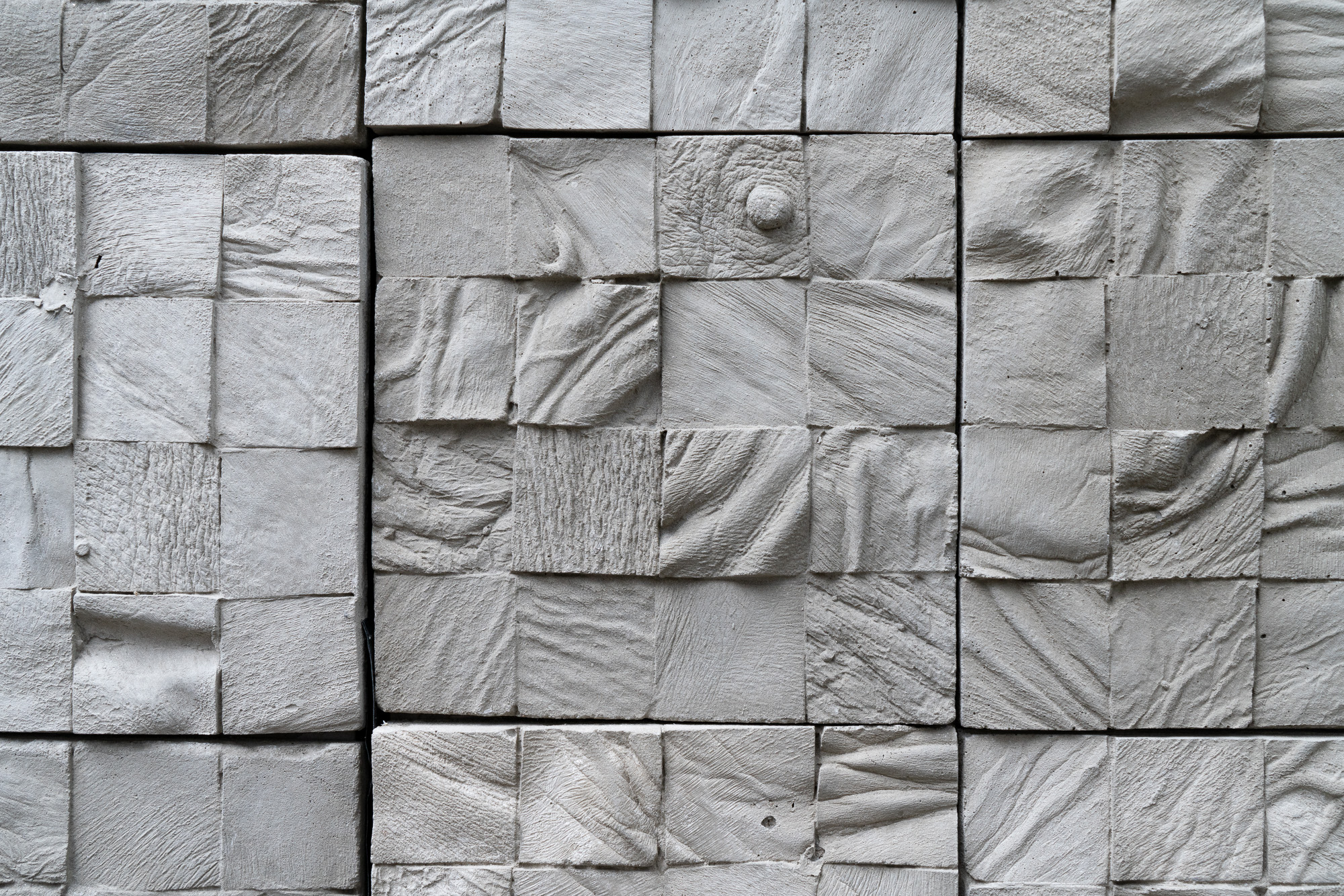

SA: Through the community-focused work Mourning August 17, 2017, I was able to ‘normalize’ death in a moment where a community was struck by death and injury in such a shocking way. The artwork assisted in helping them process and understand their loss. In 2017, a terrorist in a van zigzagged through a pedestrian road in Las Ramblas in Barcelona, killing 17 people and injuring another 130. The morning after, I responded by organizing a massive frottage [the technique of taking a rubbing of a textured surface] of the van’s path to collect the visual history of the horrible moment and initiate the grieving process by focusing the crowd into a collaborative activity. We worked together to create over 1800 A3 sized pages of pencil rubbings that expand 1800ft. You can read more about how we endured the fragility of life as a community here. It was very transformative to be able to make a work that involved so many people and directly impacted their lives. At that moment in time, I felt that art was clearly the only way to cope with the tragedy and loss.

This was the most moving piece I have ever done. Processing death is very difficult because it’s taboo in our society, and processing death through a community can be even harder, but that was exactly what motivated me. Everyone was there, standing and crying, not sure how to mourn the deaths as a community. I started the task myself, trying to find space within the crowd until very quickly people started to incorporate themselves and help me until the end. We were all kneeling and rubbing in silence and with a lot of commitment; unconsciously knowing that we were doing was something special and meaningful. By the time we finished the frotagge five hours later, we ended up hugging and crying together, all tighter and closer than we were hours before. It was a very moving and beautiful moment. There, I felt that the work definitely helped us all. Both participating and observing can be helpful as a viewer but there is something very powerful about having a community work together towards the same goal.

CN: How much research would you say goes into your process before you start working on a new series/piece? Can you walk us through your experience developing a new piece and what is involved in this process?

SA: This is a very difficult question to answer because a lot of different pieces might come from the same body of research. For instance, while I was a student at Yale, I spent most of my time at the Yale School of Medicine Anatomy Lab doing hands-on research on death and the body as an object, learning from Dr. William Stewart, PhD, Associate Professor of Surgery (Gross Anatomy), and Section Chief and mortician Phill Lapre. At the same time, I took courses like: Chinese Funerary Art, Spanish Civil War, Movements of Death, Scientific Illustration, Forensic Science and others along the same lines. Art making is a continuous labor of pulling on strands of interests and finding inner connections. Some of the research needs to be academic, but a lot of it is intuitive and sensorial—making and trying new things and finally trusting your inner self and allowing those connections to happen. It requires that you spend a lot of time on research, and all of your memory plays a role in the making.

CN: Congratulations on being the 2020 artist-in-residence at the International Museum of Surgical Science! What has been your experience so far working with their collection? What kinds of objects/materials or archive are you working with during this residency?

SA: Thank you! The International Museum of Surgical Science (IMSS) is a very special place. It has helped me reconnect with my childhood where I was immersed in surgical tools. From a very young age, I was exposed to death. My grandfather was the only obstetrician-gynecologist in his town and the surrounding area in a time when there was a higher mortality rate surrounding childbirth. His house was the hospital, I lived there for a year, sleeping in hospital beds, playing with his old wooden instruments and operating rooms. After his passing I was able to collect many of his tools, which became more meaningful after the birth of my son. We had a lot of childbirth complications that caused both of us to nearly die. Now I am able to look up close at some of the forceps at the IMSS and think slowly about how my exhibition there will take shape, and figure out how the tools speak to me. The title of the exhibition will be “Placenta Abrupta.”

CN: Your work often contains materials such as dead birds, human skin, and insect wings. Do you find these types of specimens on your own in the wild, or are they sources from nature preserves or other collections? Do you personally have a collection of specimens yourself?

SA: All of the materials I use in my work have been and will always be ethically sourced by my own hand – I carefully scan my environments to choose each new project. For one of my latest pieces Velo de Luto (Mourning Veil), I drove from Chicago to Kansas to collect the wings of the cicadas that swarmed in that year, which only happens every 17 years. I waited for them to die. I wait for all of my materials to be discarded or dead before I use them.

For a different piece that I made out of hundreds of discarded lettuce leaves, I partnered up with Stanley’s Fresh Fruits and Vegetables in Chicago. For many months, I went every morning to pick up all of the leaves that were considered not good for consumption. I dried them and used the dried leaves to construct Remains, a work inspired by the rose window in the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Pi in Barcelona, Spain. The rose window in the church is the pinnacle of religious representation in the space, and has collapsed three times throughout history. Instead of stained-glass, I used natural remains in order to elevate nature to the religious realm that the window itself symbolizes. The tossed-out lettuce from the local market gives the work a sense of humility. The window (84 inches in diameter) invites the viewer to sit in awe of the magnitude of nature’s geometry and individuality. Placing the window at eye level neutralizes the often-patronizing power that the Catholic Church often holds. It features fragility in replace of power, allowing us to embrace our intuitive response. Other than the materials I purposely collect for my work and conceptual depth, I have my own personal “cabinet of curiosities” that keeps my inspiration going, some collected by me, some added by dear friends. In it, you can find things like: a piece of my tongue, the placenta from my son’s birth, cat teeth, many different dried insects and plant parts, a human skull, etc.

CN: Because you often use biodegradable, natural materials, do your pieces decay over time? What happens to the work after this happens?

SA: My pieces are an extension of life in a way. I pick up my materials after they die, often working on them to slow down their process of decomposition. I like to think that I work in a limbo space between life and decomposition – where magic exists. The process is extremely slow; sometimes people might not even notice a change in the work. Other pieces are made of durable materials such concrete, but even when working with this material I like to leave it unsealed so it keeps absorbing the moisture from its surroundings. So in a way, I am keeping it alive.

CN: What archives/sources have been helpful to you when researching your subject and/or finding physical source material? Are there any specific texts/essays/books that were really influential for you? What would be a good entry point for someone who is interested in learning more about this topic?

SA: Every material used has a different source. Because it takes a long time to gather all the materials for each project, I have to constantly do it and be alert. That is why some of my projects take years! As an example, for the piece with cicadas, I had to monitor scientific websites where they had predictions of where and when cicada broods were going to occur. I also used an app called Cicada Safari where people can upload images of cicadas when they see them, and you can get an idea of where to go and when. This was very time sensitive since their lives are so short. I have been also collecting wasp nests for an upcoming installation. Wasps die or inhabit their nest after the first freeze of the year. During the fall, I spot them and write down the addresses where they construct their nests and then wait for them to die to pick them up.

It may sound strange…but the books that were most influential to me are very intimate. Growing up, I was very passionate about Edgar Allan Poe’s stories, Frankenstein by Merry Shelly and Romantic poets like Keats, William Wordsworth, Jacint Verdaguer… and La Plaça del Diamant by Mercè Rodoreda. Recently I found it very helpful to read: “The Performative Corpse” by Bethany Tabor. In it, the author examines the work of Teresa Margolles, the human body as an object, and the specifics on exhibiting human remains. A good entry point is through observation and exposing yourself—to be vulnerable. Look around you. If you see a dead insect, take a closer look at it, draw it, and think about your own death and the ones you love. If someone close is dying, stay by their side, draw them, and spend time with them.

For the past few years I have collected written wills from people that have unconventional death wishes and want me to make them happen. It has been an honor to start this project and have people trusting the very idea with me. This might be an utopian idea, but I believe that my work may help the viewer to think about how we are processing death, especially in these times, and even begin to think about how to deal with one’s own death.

CN: Do you have anything coming up you would like to tell us about? When is your solo exhibition at the International Museum of Surgical Science?

SA: I was recently chosen to be one of the 2020-21 Bolt Residents and will be participating in an exhibition at the MCA in November 2020. The solo exhibition at the International Museum of Surgical Science will open in October 2020. Thanks to the MAKER Grant funds, I will continue my research at the morgue and start a project where I plan to create a monument in honor of donors. I am waiting for responses from a few exciting art-related things I have applied to! Stay tuned.

Featured image: Selva Aparicio, Entre Nosotros (Among Us) Detail, 2020. Concrete tiles cast from human cadavers. The images show a close up of the piece, showing details of a grid of square, concrete blocks. Each block has different folds, and one shows a nipple, all cast from human parts. Photo by Robert Chase Heishman. Image courtesy of the artist.

Christina Nafziger is a writer, editor, and curator based in Chicago. Her research focused on performativity within the image and the effect archiving digital images has on memory and identity. Her recent writing investigates the work of artists with research-based practices as well as the role of the archive and its capacity to alter and edit future histories.