It goes without saying that so much of the labor in an artist’s practice goes unseen, ranging from the countless hours of trial and error experimenting with a medium before getting it right, to the often mind-numbing planning and prep work when starting a new piece. However, there is yet another layer below the surface of this complex production that is inherent to the creative process: research. There is a collection of information, images, and archives that happens even before any pen is put to paper, feeding, and informing an artist’s body of work. Works Cited asks artists to uncover this part of their practice with us, sharing research materials such as essays, playlists, online archives, and tips on how to navigate them. In the spirit of open access, this column also serves as a resource in and of itself, as each interview includes access to these materials in the form of either reading lists or sharable links.

In this edition, I spoke with Marzena Abrahamik, who explores the transformative experience of psychedelics in her work, harnessing the capacity this has to connect us to each other and nature. Through her research in brain chemistry, Abrahamik chooses to include objects in her work that affect our serotonin and dopamine, like plants and flowers. Through photography and video, she conjures scenes of mystic and wonder, manifesting an undeniable essence of the feminine power. The presence of fruit in her work draws together a balance of fecundity and female pleasure, and also a nod towards the ‘original sin’ and the femme fatale. Originally interviewed in the throws of deep quarantine, the artist was scheduled to be part of a two-person exhibition titled From a Strange Place at Heaven Gallery, which was postponed due to COVID-19.

Over email, Abrahamik and I discuss the cultural roots of psychedelics, the way she uses certain objects to create a connection with her sitters, and the work that would have been on view as part of From a Strange Place.

Reading List/Resources:

- https://maps.org

- The Psychedelic Salon Podcast

- Sisters of the Extreme: Women Writing on the Drug Experience by Cynthia Palmer

- How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence by Michael Pollan

- The Psychedelic Explorer’s Guide: Safe, Therapeutic, and Sacred Journeys by James Fadiman

- Fantastic Fungi: How Mushrooms Can Heal, Shift Consciousness, and Save the Planet by Paul Stamets

- The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead by Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert, Ralph Metzner, Daniel Pinchbeck

Archive List:

- The Betsy Gordon Psychoactive Research Collection at Purdue University

- The John Hopkins Center for Psychedelic & Consciousness Research

Christina Nafziger: I understand that you were going to be part of a two-person show with Jordan Martins at Heaven Gallery, which was canceled due to COVID-19. Can you tell me about the work that would have been in that show? Is it new work?

Marzena Abrahamik: The work at Heaven Gallery has not been exhibited previously. The video piece I started in 2012 while in grad school sparked by my desire to watch, interview, and document the experience of a person ingesting ayahuasca. I was particularly interested in the disconnect between my visual experience of them and their physical experience of ingesting the root; on the surface it did not look like much was happening, yet the person was undergoing a profound transformation. I wanted to channel that through photography and video. But it was not until Jordan Martins agreed to collaborate on a two-person show, and Heaven Gallery accepted our proposal, that I began to get over the stigmatization [of using psychedelics] and reflect on my past experiences.

CN: Can you tell me about your interest in the cultural history of hallucinogens? How did you become attracted to this topic?

MA: In many ways, this work draws inspiration from years of my own observations and experiences of non-ordinary states of consciousness. Psychedelics speed up the reception of information and its integration into consciousness. I immediately understood the deep insight offered and [the] transformative potential from my first trips. I fixate upon the moments in my life, and other people’s lives, that have the capacity to transfigure. I find a resource of power in this commonality of experience, in the archetypal transcending events that we all share. For example, a 2011 study by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine stated that 94 percent of participants who received psilocybin reported the experience as one of the top five most meaningful experiences of their lives, and 39 percent said it was the single most meaningful experience. I can relate. I feel profoundly connected to the person I first took LSD with. For that interconnectedness/first-love and the bottle of lemonade, I am forever grateful.

Another study that re-enforced my determination to make work around psychedelics was done by Imperial College London’s Centre for Psychedelic Research. In this study, the researchers found that nature relatedness was significantly increased even two years after the psychedelic experience. They also found that the participants felt a stronger sense of “well-being” when their attitudes toward nature increased. Not only do psychedelics re-connect us with nature but that connectedness also makes us feel better. It is this interconnectedness and desire for that connection that drives my work.

CN: There are certain motifs that appear to be a recurring theme in your work: fruit (and food in general), flowers, and many, many plants. These objects are often displayed in a manner that brings to mind Dutch still life paintings or vanitas. Was this intentional? What are your interests in these objects and how do they relate to the themes in your work?

MA: Vanitas still lifes were conceived as meditations on our fragility. They are characteristic in their melancholic mood, often pointing towards one’s wealth (ex: lemons), ephemerality of learning (ex: hourglass, skull, and books), and death (ex: flowers that have a short life span). In a similar way, I use pot leaves, moths, wine, pastries, bongs, hummingbirds, oysters, and shells as pictorial typologies that infuse my work with the sensual pleasures of rebellion in mass culture. The pictures’ subject matter has to do with [the] transformation [of] a feminine domestic life—single, with roommates, partners, and now with dependents. Initially, I included pot as an antagonist; I felt the work was more aggressive, irrational, and resistant with cannabis in it.

The combination of elements is important. Fruit is associated with female curiosity, especially in varying art historical canons. I am interested in employing this iconography to further implicate an idea of original sin where “woman” is linked to fruit and dangerous allure. I hope to offer an alternative, where ritualized consumption and an elevated goddess-consciousness converge. One artist I keep going back to is Rachel Ruysch. She is forever a reminder that a great understanding of one’s medium (subject, composition, use of color, detail) and the techniques of earlier traditions can allow work to become, rather than be labored into being.

[My series] Girl Play was at the beginning of thinking about how I can complicate preconceived notions of the non-nurturing feminine; pivoting from [the] Virgin Mary and Athena to the Sirens of the Odyssey, Medusa, Salome, and Kali. The series was a procedural articulation of a feminine that is rebelling, engaging in vices, mysterious and unapologetic, yet forever tied to the fundamentally human: birth and death, pain and pleasure.

When I photograph in people’s homes I bring flowers because I read that brain chemicals such as oxytocin, dopamine, and serotonin are released by a positive reaction to flowers. These brain chemicals trigger feelings of bonding, excitement, and happiness. Carbs and alcohol do that too, so I bring wine and pastries. I create an environment where we (me and my sitter) can connect and relate by sharing stories, experiences, and ideas.

CN: Do you use sourced imagery as references in your work? Where do you find them and how does this process feed into your practice?

MA: I wish that there were more representations of women in relationship to cannabis and psychedelics. Most of my photographs are a re-make—a staging of a personal experience, mine or someone else’s. I am interested in how experiences are made recognizable and translated into a photograph/film/sculpture. My photographs investigate how these experiences are redesigned and held within our memory, and how, once captured in our past-experience, they relate to semiotics, sensibility, and overall appearance. I am also interested in how experiences impact our identity and form individual myths. For example, Odysseus’ journey home is his entire identity. Psychedelic experiences are referenced as “trips.” This semantic bridge fascinates me: one psychedelic experience, through its distorted perceived duration, has the potential to change us and redefine our identity. The psychedelic trip awakens awe, a different kind of awareness.

CN: How has your research influenced, inspired, or changed the path of your work?

MA: My research bolsters my drive to represent an ordinary feminine drug experience. I became obsessed with researching psychedelics when I joined the Psychedelics And The Future Of Psychiatry group. Dr. Matt Brown recommended a few books and connected me with Dr. Fernando Espi Forcen with whom I instantly connected with. Then, I had the opportunity to visit Purdue University’s unique archive on psychoactive substances research. Stephanie Schmitz, the Betsy Gordon Archivist for Psychoactive Substances Research, was helpful in navigating this massive archive. For the most part, I concentrated on the inventory of the Stanslav Grof papers, circa 1955 to2012, and The David E. Nichols papers.

This collection contains writings that document the career and research interests of psychiatrist and author Stanislav Grof. It consists primarily of published research articles and clippings discussing the therapeutic effects of psychoactive substances as well as some first-hand accounts of transcendental experiences. Grof links the hopelessness of a bad trip with the process of being born. During a personal LSD session Grof experienced a sense of pressure on his jaws and head, he felt trapped and made the realization that he was reliving his own birth and the trauma from it: the trauma of coming out of a cosmic union, being crushed by the mother’s body, then into the world with a new beginning.

One of the reasons why I chose to birth with the Midwives at West Suburban Hospital is because they offer laughing gas anesthetic as an alternative to the epidural. My birth took a complicated turn and ultimately I had an epidural. It was a scary delivery. When the doctor finally ripped the baby out of my body, placed the baby on my chest—and while still connected through the umbilical cord—the baby picked up his head and locked eyes with me. It was all there: the singular vision, confidence in my body’s survival, transcendence of time and space, overwhelming feelings, and insight.

CN: I’m curious about the cultural history of psychotropic substances—does this history involve the use of these substances for religious/spiritual purposes?

MA: There are threads within the historical that articulate a system of transference, a methodical extension of consciousness, conducted and achieved by women through psychedelics. I draw extensively from figures such as Maria Sabina of the Mazatec, who used psilocybin mushrooms in rituals, and the priestesses that conducted the Eleusinian Mysteries in Greece for two thousand years.

The work in From a Strange Place emulates a potency in static capturing. This tenuous space was inspired while I was considering imagery from the Paleolithic era. Some believe that the mythical creatures, such as the “Mythic Beast” (a double horned unicorn) from the Lascaux cave, have ritual and magical significance. Also, the paintings found in other caves, of figures with combined human and animal characteristics, represent ancient shamans. This excites me—this permeating ritual significance that communicates from the ancient, as captured in these images.

Ever since I was a little child, I have craved transcendental experiences. I wanted to be out of my body; dreamt of tranquility and infinity. Rites of passage such as my first love, my mother’s death, marriage, and my son’s birth have all transformed and redefined who I am, more or less similarly to the way psychedelic experiences have. Something is left behind and a new way of being takes over.

Medical communities’ embracing of hallucinogens as therapeutic treatment was stilted when LSD and psilocybin were added to the 1970 Controlled Substance Act as Schedule I substances. They were deemed to have no medicinal value and federal funding for research is still unavailable.

Today, there are a few other research groups in process on the uses of psychedelic drugs: recreational, medical, personal, and therapeutic. There are many positive results from using these drugs in treating cluster headaches, alcoholism, depression and anxiety, end of life issues, and PTSD. Effects are said to include an increased openness to new experiences and belief structures. I also heard Tim Scully, chemist and maker of Orange Sunshine on the MAPS podcast, say that, even though psilocybin has distinct effects on social cognition by enhancing emotional empathy, psilocybin and LSD are not a cure for being an asshole.

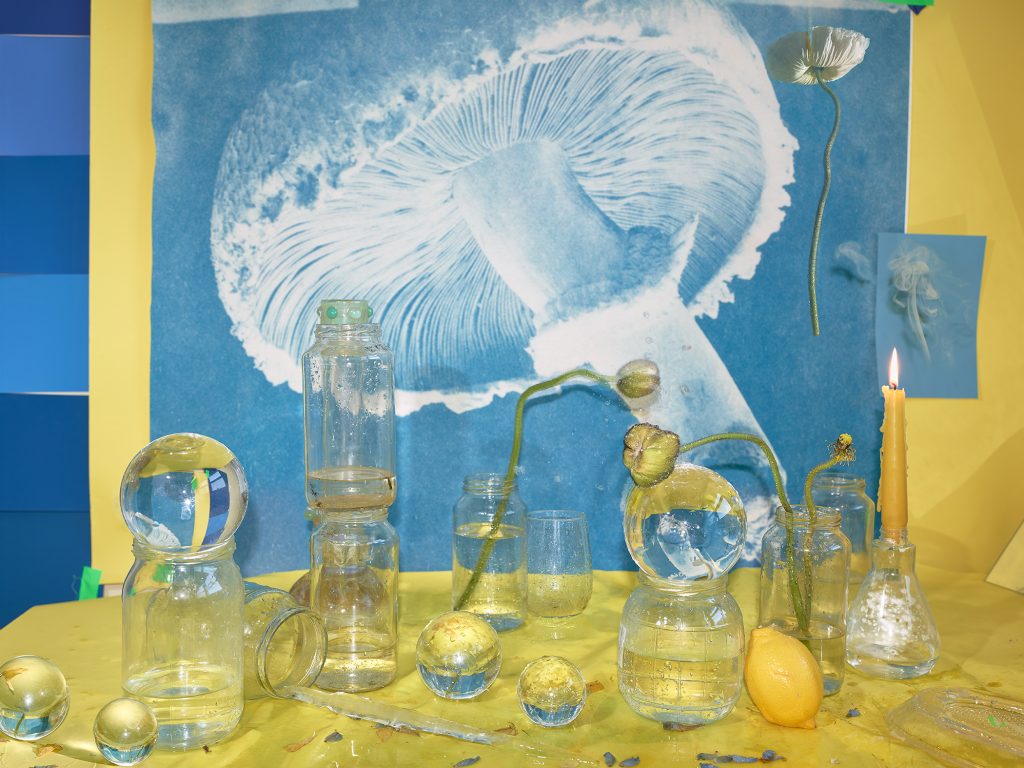

Featured image: The Six, 2020 by Marzena Abrahamik. A photograph of a still life of an orange and red bouquet of flowers on an orange-yellow table. On the table also sits oranges and various plant parts. The background is also orange-yellow. Image courtesy of the artist.

Christina Nafziger is a writer, editor, and curator based in Chicago. Her research focused on performativity within the image and the effect archiving digital images has on memory and identity. Her recent writing investigates the work of artists with research-based practices as well as the role of the archive and its capacity to alter and edit future histories.