The following article is part of Unreasoned Scores, a series of six articles edited by Fabiola Tosi, Juelle Daley, and Stephanie Koch, the 2019-2020 HATCH Curatorial Residents with Chicago Artist’s Coalition (CAC). When social distancing posed a challenge to building community between the artist residents of the program, Daley, Koch, and Tosi created a structure for artists’ interviews which asked: How can we be isolated together?

Through a series of exercises, curators encouraged artists—paired together based on artistic practice, experience, and personalities—to connect through a series of interviews with one another. The goal was to foster a human-scale connection between artists, beyond the hyper-mediated space of online meetings.

With this experimental editorial project, the curators seek to investigate “How does one archive ephemeral works which may not fit the formats of a traditional archival record?”

Read part 2 of Unreasoned Scores featuring artists Ellen Holtzblatt and Salim Moore.

Katie Chung and José Santiago Pérez, edited by Fabiola Tosi

When meeting someone for the first time, maybe even after a few conversations, you would get to know a person through the lens of how they describe themselves. We introduce ourselves by tailoring an image of our identity, using storytelling from us about us. We present to others using an inward-looking perspective, based on our own experience of the world. But what would it mean to build a picture of yourself through the voice of someone else?

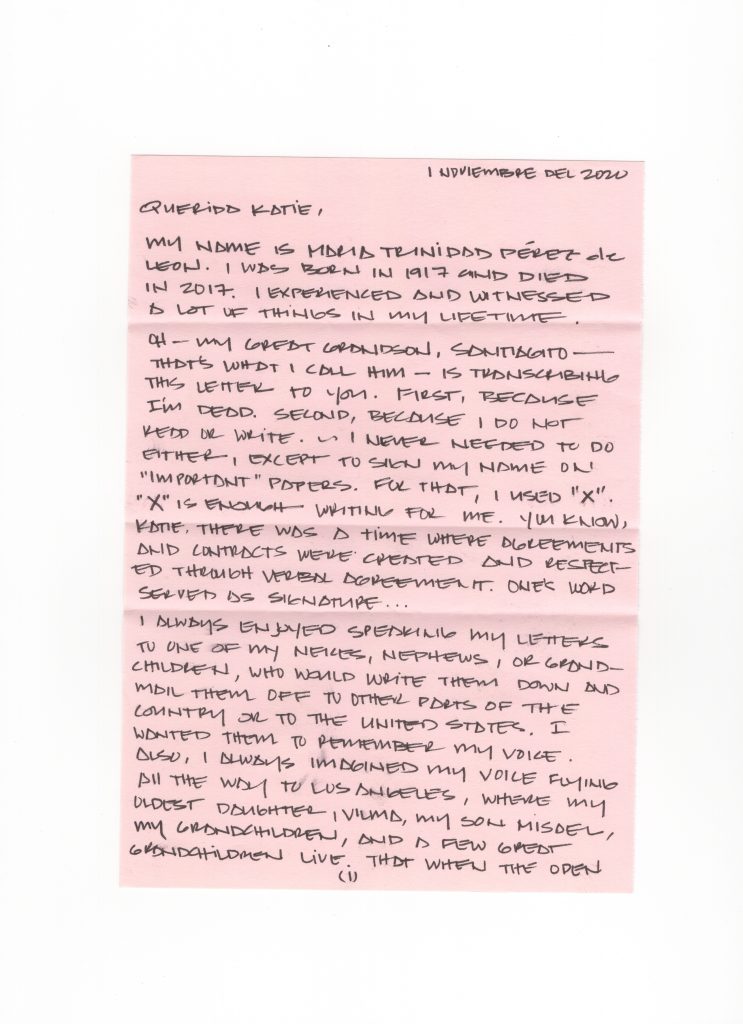

Through letter exchange, artists Katie Chung and José Santiago Pérez attempted to present their identity and history by shifting the narrating voice of their recounts from the self to an otherness. At the beginning of their process, they asked “How do you tell a story about yourself through the history and experience of the ones who came before you? How can you show implicit and explicit influences that your ancestors left imprinted on your identity?” Chung and Pérez each wanted to record the ephemeral relationship with their ancestors by telling their individual stories through the voices of their grandmother and great-grandmother.

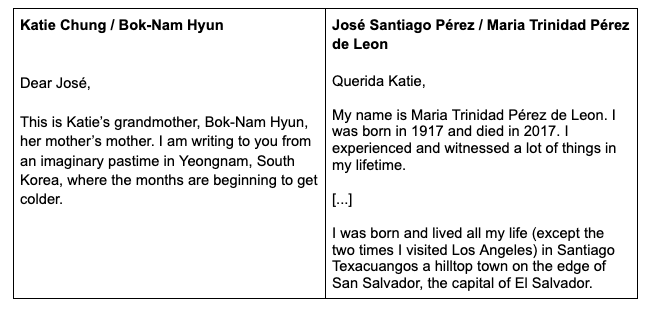

The artists decided to subvert the subject of the interview and turned to their ancestors in search of a speaking subject that could act as an external and internal narrator at the same time. They wrote letters to each other as if they were dictated by their late family members. Chung assumed the voice of her grandmother, Bok-Nam Hyun born and raised in Yeongman, South Korea. Pérez wrote words inspired by his great-grandmother Maria Trinidad Pérez de Leon, who lived her entire life in Santiago Texacuangos, a municipality of San Salvador, capital of El Salvador.

With two handwritten letters, Chung and Pérez created a unique and complex network of relationships, some of which are imagined, idealized, desired, others meant to be cultivated into their everyday reality; some prescind from temporal designations, others will become a framework for the present and future. The two artists salvage these relationships from their inherent ephemerality, by inking them down on paper.

The first question the artists try to resolve is: “Who are Katie/Bok-Nam and José/Maria Trinidad?” The two letters provide some insights on the origins of the two speakers.

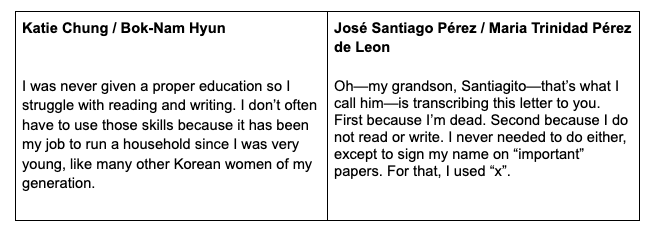

We get to know Katie/Bok-Nam and José/Maria Trinidad through their life experiences, some of which reveals deep connections between the two correspondents, thanks to their similarity.

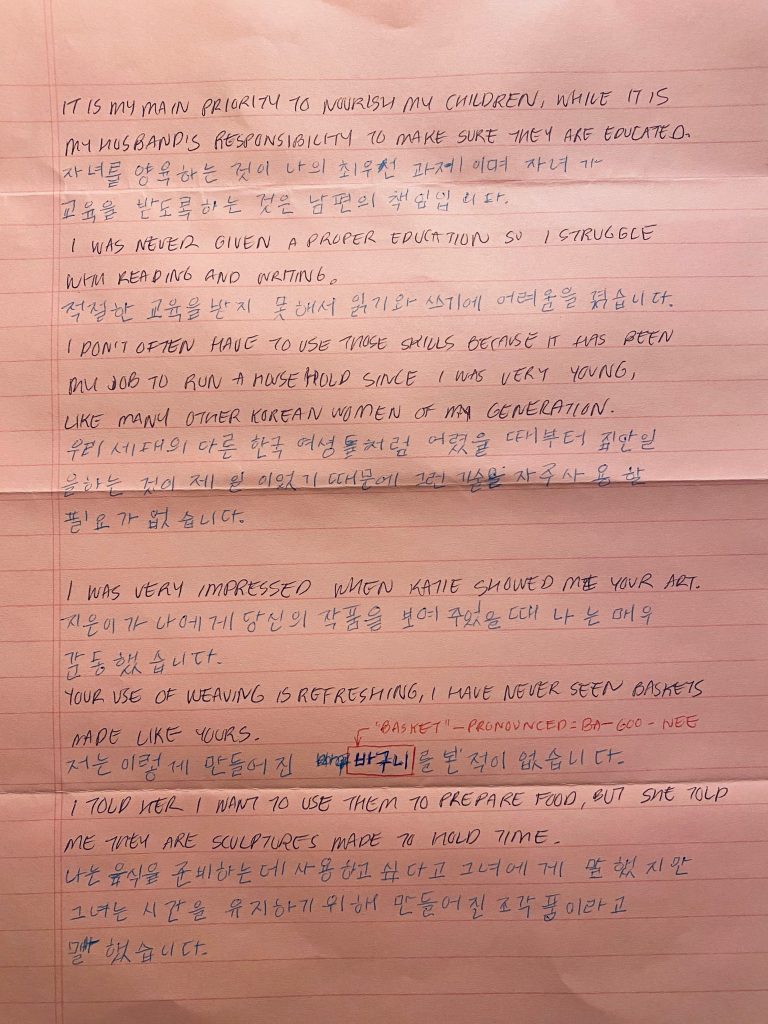

Throughout these letters, we can perceive the different relationships that the two artists had with their ancestors. Similarly, Chung and Pérez surveyed their individual identities by questioning generational differences with their grandmothers, and the influence that these changes and evolutions had on them. Bok-Nam had recently passed away when Chung began to write the letter and she realized soon enough there was a lack in her knowledge of her grandmother’s life details. As part of the process of reclaiming her identity, Chung practiced the writing of Korean characters. In this context, the artist wrote the letter in both English and Korean, letting her grandmother’s identity join and shape her own, as this simple gesture becomes their point of contact. On the other hand, Pérez reports a quite detailed account of his great-grandmother’s life, through which he draws evident connections with his current artistic practice. Maria Trinidad’s husband was a weaver. As she writes “My husband and his three older brothers wove cotton yardage to sell. I did all the business transactions and deliveries.” Though the business died with her husband, Maria Trinidad would “like to think that Santiago would have followed the traditions if he had been born in Santiago Texacuangos.” In a way, Pérez did follow that tradition now that he’s exploring weaving practices through art, his own point of connection with family history.

In this complex network of relationships, there are evident direct connections between Chung and Pérez that begin to form on paper. In her letter, Chung gifts her fellow artist with the Korean characters of 바구니 Basket and 가족 Family, two guiding principles of Pérez’s current practice. Similarly, Pérez provides Chung with guiding questions to explore even further her relationship with Bok-Nam: “What else can I share with you Katie, now that we are in relation? I would ask you about your great-grandmother. Where was she born? Where was her great-grandmother born? What would she say about her life? About you? Who’s [sic] hands do you have? Who transcribes and translates her voice?”

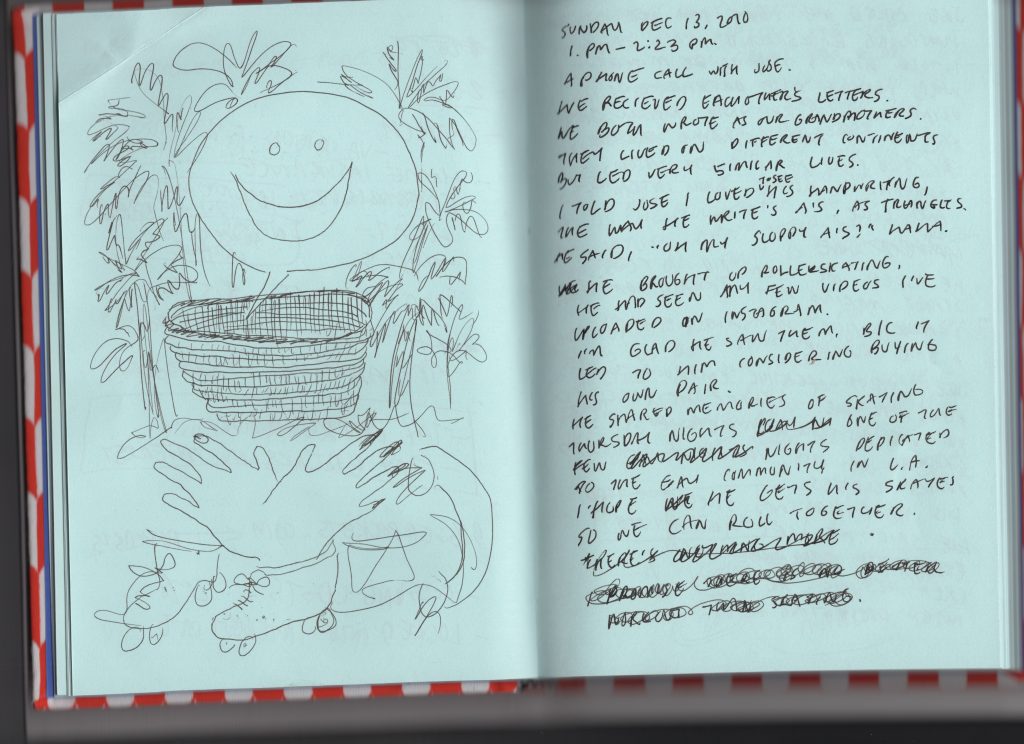

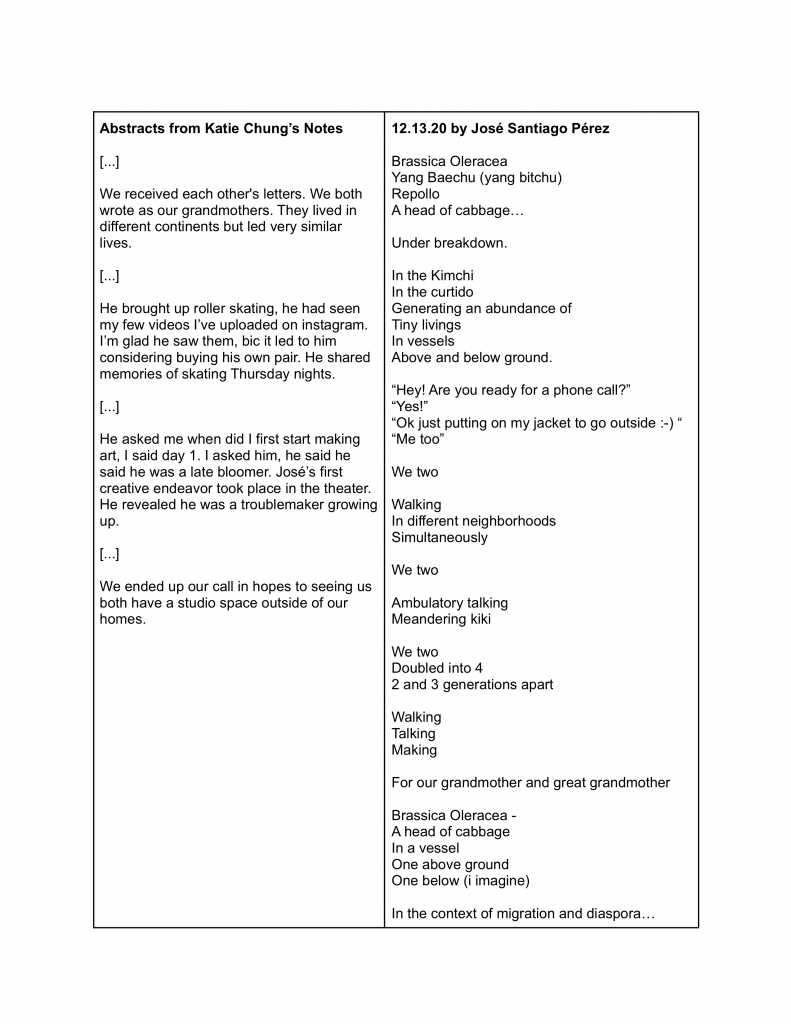

After exchanging letters, Pérez and Chung decided to have a long phone conversation, to share thoughts on their experience with the Unreasoned Scores project and talk about their art practice, hobbies, passions. Chung took detailed notes of their conversation, and Pérez decided to transcribe them into a poem.

Through this experimental approach, Chung and Pérez created unique evidence of a network of interconnected relationships, savaging them from the ephemerality of time and space. Their letters, notes and all other media they were able to produce and collect, stand as evidence of their familial ties, but also of the intersectionalities between their individual experiences.

At the end of this process, the artists rendered each other’s portraits through objects that speak to their individual personalities, histories and identities. Pérez weaved together roller skate laces, those colorful safekeepers of the skater’s balance. He embroidered beads in the thread, honoring Chung’s artistic practice and her use of small and dense stitching. The theme of connection through knots returns in Chung’s rendering of Pérez. Once again incorporating parts of each other’s artistic practice, she used scrap materials to create a timekeeper, folding and waving pieces together with a gesture similar to Pérez’s. Numbers indicate the empty spaces between individual elements, bringing the attention to the invisible that makes connections possible, an act of care toward an ephemerality that has all the qualities of a relationship built through time.

José Santiago Pérez is a Salvadoran-American artist and educator from Los Angeles currently based in Chicago. He weaves plastics into markers of time, materials of intimacy, and spaces of belonging.

He is a 2019-2020 HATCH artist at the Chicago Artists Coalition and a recipient of their SPARK grant.

Katie Chung earned her BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2014. She has exhibited work in Los Angeles, Chicago, and Milan, IT. Chung was a member of Candor Arts, a Chicago-based resource for the design and production of artist books. She has held artist residencies at Jacmel Art Center (Haiti); Lillstreet Art Center; the Center Program at Hyde Park Art Center; and Facebook. Chung is a 2020-2021 HATCH Resident Artist at Chicago Artists Coalition.

Fabiola Tosi is a Chicago-based curator and arts administrator. Originally from Italy, Fabiola is an experienced project manager promoting international cultural exchanges. Her curatorial work aims to unveil cross-cultural practices as a platform for discussion around politically and socially engaged issues. Fabiola is the current Exhibits Project Manager at the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum in Chicago, and formerly Assistant Director of Exhibition and Programs for the US Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2018. In 2017, she received her MA in Arts Administration and Policy from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.