As the raspy voices of Erykah Badu and Outkast reverberated inside the white walls of the Gene Siskel Film Center, the opening reception for Hot Seven: The Chicago Breakdown unabashedly filled the gallery space with Black culture. This is the second exhibition in the Hot Seven series by curator Sadie Woods, who is currently a resident artist at MANA Contemporary and was recently resident curator for the Chicago Artist Coalition’s HATCH projects.

On view until September 25th, Woods highlights 7 emerging artists of color from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, who innovatively manipulate the medium of film and video to resist dominant modes of representation in American visual culture. The gallery space’s narrow hallway of video screens and photographs are successful at collectively exploring the new narratives being spearheaded by artists of color in the Black diaspora today.

The video works of Amanda Gutierrez and Roberto Martinez shed light on the intergenerational disconnect felt between parents who have immigrated to America, and their children born in the United States. The split screens of Martinez’s work make a visual statement about the cultural clashes that can occur between family members born on different soil. It convincingly captures the viewpoint of a parent, evoking the internal turmoil that immigrant parents experience when struggling to assimilate, while they still attempt to hold onto their heritage.

Gutierrez’s piece, in particular, relies on sound and static urban spaces to communicate intergenerational sacrifice. The viewer hears sounds of trains, sledgehammers on a train tracks, yet sees empty post-industrial landscapes. Images of barren spaces communicate the idea that something is lost when migrating and settling between different spaces that one aims to call their home.

Darryl Terrell’s photographs introduce a fresh conception of masculinity in the American context, boldly redefining its boundaries. Recently featured in Afropunk, Darryl Terrell’s captivating photography greets the viewer with portraiture of African-American male faces, seeped in chiaroscuro shadows of Black and brown. Vibrant plant forms delicately frame his subject’s faces in areas where the viewer would least expect vegetation to appear: tucked away in facial hair, afros, and fedoras. Their countenances, however, are full of sensuality and joy.

Joe, for example, features white luscious petals emerging from sections of the face where hairy beards normally grow. It uses the male form to instead present the viewer with tenderness and emotion, as opposed to aggression. Terrell demonstrates that masculinity can be vulnerable, emotive, and gentle. His overt engagement with aestheticizing male vulnerability, a quality rarely explored in Black mainstream pop culture until artists such as Frank Ocean, puts an image to a new expression of Black masculinity. Queer, Femme, and Black all have a voice in Woods’ Hot Seven.

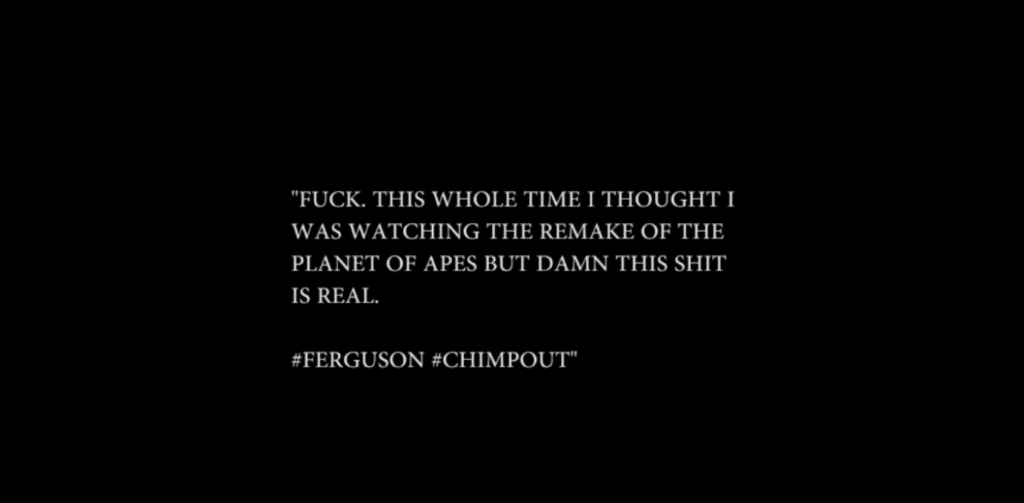

The artworks most explicitly dealing with the medium of the digital, however, are most successful in the show’s mission to “re-examine social responsibility.” The video work of Darius Thomas, for instance, engages with the complexities of being saturated in a virtual world of social media, rampant with endless hashtags and the looping video footage of Snapchat and Facebook live. It represents the way in which artists of color cannot escape their racially-infused social media feeds, even if they had the choice. The video stills that begin Thomas’ video work No More Hashtags present the viewer with the frankness of unfiltered social media posts and hashtags that can oftentimes be triggering for millennials of color in our era.

By witnessing and hearing words like “ape,” “tribalistic,” “Chimpout,” “#Icantbreathe, and “#Make American Great Again, “ Thomas recreates the experience of a person of color scrolling through their a Facebook feed during socially tense moments with protest and social injustice. The spoken word poem being recited in the background of the video work problematizes the phenomena of creating a social media hashtag when individuals like Mike Brown, Trayvon Martin, and Sandra Bland were brutally executed by the police. The work evaluates the worth of a hashtag in relation to the lives that are lost through senseless police brutality. No More Hashtags asks:

“[Was it] worth the 38 seconds Eric Garner was held in an illegal chokehold?

How about the 83 years Trayvon Martin had left to live?

That had to be worth something”

While the footage in the video work feels disjointed from the audio of the video itself, the anecdotes expressed throughout the poetry successfully note that Black lives matter only once they become a viral hashtag on social media.

The different works within Hot Seven: The Chicago Breakdown bring a satisfying balance of the audacity and subtlety required to reestablish new narratives for the experiences of communities of color in 2016. It uses the bold cultural agency of the artists to represent an America that will only be great by fully including the diverse voices already present within it.

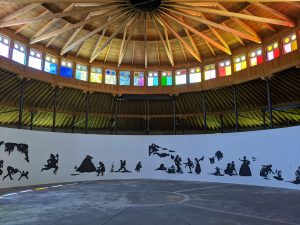

Featured Image: Hot Seven exhibition installation view. (Image by Sadie Woods.)

Sabrina Greig is an art critic in Chicago, originally hailing from New York City. She received her MA in Art History from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago with a focus on representations of the Black diaspora in pop culture, fine art, and gentrified urban spaces. Sabrina is a current curatorial fellow at ACRE projects located in Pilsen and has curated shows at the Haitian American Museum of Chicago as well as the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her literary work has been published in Fnewsmagazine and Bad at Sports.

Sabrina Greig is an art critic in Chicago, originally hailing from New York City. She received her MA in Art History from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago with a focus on representations of the Black diaspora in pop culture, fine art, and gentrified urban spaces. Sabrina is a current curatorial fellow at ACRE projects located in Pilsen and has curated shows at the Haitian American Museum of Chicago as well as the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her literary work has been published in Fnewsmagazine and Bad at Sports.