Champaign-Urbana is home to a multitude of artists and creative people. The visual arts community in C-U is one that can, broadly speaking, be divided into three groups: local artists with no institutional affiliation; faculty, staff, and students at Parkland College; and faculty, staff, and students at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. As a whole, they generate a vibrant intellectual and creative energy not often found in other similarly sized cities.

The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s School of Art + Design has nationally and internationally recognized faculty working in all media, but there aren’t very many opportunities to spend time with faculty artwork here in C-U. As faculty at a research-focused institution, they regularly have successes at the national and international levels. The combination of only a handful of exhibition spaces in C-U, and the university’s encouragement for non-local exhibitions and lectures, makes it common to know someone fairly well but have a very hazy sense of their creative work and research.

I first met multimedia artist and UIUC Teaching Assistant Professor Guen Montgomery when she moved here about six years ago. In that time we’ve had short conversations about her creative research practice, and despite her impressive and rigorous exhibition history, I’ve only experienced her work locally through the annual School of Art + Design Faculty Exhibition at the Krannert Art Museum. Montgomery makes art in all different media, and no matter the material, I find her work to be very compelling. There’s a detailed attention to craftsmanship and elegance to the aesthetic of each object or video. Everything seems to be intentional, but never overworked. Even in her performances, I am drawn in by the visual—there’s something beautiful, familiar, and approachable—but upon closer examination I realize something isn’t quite right. There’s a wry darkness and humor there, but it’s never gimmicky or sardonic.

Montgomery has a background in printmaking, and her studio is in the same building as the School of Art + Design’s Noble Ink Lab, the print shop that serves the school’s students and faculty. After visiting her studio, we sat down and talked about her practice and specifically about the topics of gender performance, collecting things, violence, and death. We kept returning to two bodies of work: a series of collagraphs (prints made from material objects) featuring women’s undergarments, and a set of antique irons etched with drawings of small, dead animals.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Jessica Hammie: Let’s start with a short overview of your practice. How would you describe it to someone who doesn’t know anything about it?

Guen Montgomery: I have a history and background in theatre and I can’t seem to get away from it even though I switched into printmaking and art. I feel like I am always thinking about character, and scene, and costume, and even affect. Those are things that are interesting to me and I have found ways, whether consciously or inadvertently, that they’ve snuck back in to my work over the years. I switched from theatre into printmaking because I love process. I really love the act of making. There’s something about the transformation of putting an image through a press that feels like a kind of alchemy; there’s a magic there that I have always really loved. I like things that have steps—I just enjoy step-based and process-based making—but it’s also the evidence: The fact that printmaking is a remnant or a residue of something that has happened—it’s a record. I’m a big fan of procedurals and true crime…I just love the idea of a trace left behind, and printmaking is very much that. There’s kind of a drama in printmaking, in this moment of reveal. My work right now is pretty interdisciplinary. Printmaking is definitely a core part of it, performance is a part of it, and then there are these other interests that I keep pulling back in, like fiber, and sculpture, ceramics. It ends up being that my work is conceptually grounded around a few themes and then I determine what medium or material I’m going to work with based on what I feel is most appropriate or what expresses it the best. Sometimes that means a thing has to be embodied, so sometimes it means performance and sometimes it means two-dimensional work. More and more though, it’s objects, and object-based making. I think that my work will continue to grow towards sculptural direction, whether that be ceramics or fibers, or using sculptural things in printmaking.

JH: You mentioned the themes that you see across media. What are the themes that you think unify your work?

GM: I think that there are some really obvious ones, which is gender, and the performance of gender is a huge part of that. Thinking about gender as a performance, but not a performance in that it’s a facsimile, but that it’s something that we truly believe, that we are invested in that feels right or true to us, in whatever we choose to perform, or as a performance that hasn’t been examined in some cases. Natural lineage and heredity were really important to my early work. I was really interested in family genealogy and how the differences between my mother, who grew up with one pair of shoes for the entire year and eating squirrel, and myself, who is an only child and by the time I was 12 I had been to Africa and Thailand and we lived in Hawaii…just the privilege there and the gap between our experiences. I’m an only child and she came from a family of 9 children in Appalachian poverty. And yet we look so much alike, our behaviors are so much alike and there is so much that feels like I’m looking through a future mirror when I look at my mom. So that has really fascinated me for a long time and watching her perform femininity and then realizing that I am imitating those performances of femininity as I age. Age is something I have really been interested in: aging female bodies, and how we age, what society expects from us as we age, and how we grapple with time. I think a lot about our bodies as impermanent in relation to objects, which are permanent. I try to think about how to depict time, bodies, and objects. I am fascinated by possessions and our relationship to possessions, and it comes back to the idea that they are outliving us and that they also can be a kind of a portrait of us, that they depict us.

JH: When I think about your work I think about collections, I think about storytelling, especially in the Appalachian tradition of storytelling and the way that can be done through objects and material goods. So, these stories that people are telling themselves in what they’re collecting, and the stories that people close to them tell about them through the collections, and the detritus…it’s more residue, and I think about that in terms of your print practice.

GH: Exactly. The things left behind. I find that really interesting. Collections are a way to freeze time, to preserve something in a way that we can’t. There is something really desperate about it. I’m really into that and saddened by it also, because it’s compulsive! I mean it’s a family compulsion to hoard and collect things. My grandmother collected these specific porcelain dolls where the ceramic was made from lace dipped in slip. And my mom collected these glass vases that are all teal and she collects teal things of all kinds, basically. She collects cat figurines, for a while she was collecting dolphins.

JH: Dolphin figurines?

GM: Yeah, not real dolphins, but if she would if she could. My aunt is basically an all out hoarder. There is an interesting fine line between hoarding and collecting and I heard once it’s curation. And my mom definitely curates these things so it’s all on display. My uncle collects these—he’s sort of an Anglophile in a problematic way, and collects these beautiful blue Wedgwood-looking ceramic ware, plates and dishes, very feminine looking things for a proud NRA-supporting Appalachian man. So, I like that part of it, revealing part of something of him that we wouldn’t otherwise see.

JH: And might only you see if you’re in his home; in an intimate way like sharing a meal.

GM: He collects things from—like beer steins—from Germany. And his obsession with Germany comes from being over there as a young man. He went and served in Germany for a while. He remembers his youth through his service in the military and so a lot of the things he collects are ways of preserving who he remembers himself to be, like a moment in his life that was better than the other moments.

JH: Or so he thinks. I’m always a little freaked out by nostalgia. We see now it played out on a national scale in our politics, like, so explicitly. So I wonder, too, how you think about nostalgia and collections.

GM: Yeah nostalgia is really dangerous. This is actually a good line of questioning. Just like collections where it’s like I want to keep all these things my mom collects after she passes away, all of her teal vases, I’m not going to be able to throw that away, but the burden of having that is terrifying. The desire to look back and re-imagine things as more perfect, and more unsullied…

JH: Hindsight is 20/20, kind of rosy?

GM: Yeah, yeah. It’s creepy, I agree. I also think we can’t seem to help ourselves from doing that. Memory is really funny that way; it really shaves off the hard edges. And we miss things that we think we remember, you know? I personally have a pretty dreadful memory and I know that I have a desire for things that I am not sure whether they were that way or not, so I feel like it’s time manipulating me emotionally. I also am really fascinated by that need to anchor yourself to a past and the desire to be somewhere that feels like it was real for you once.

JH: Even if it wasn’t.

GM: Right, yeah. There are anecdotal stories about people who’ve remembered trauma that doesn’t exist. Our memories are so impressionable that you can falsely remember things. The first-person witness studies show that it’s flawed and nostalgia is really disturbing to me in that way because it seems like, especially in our current political climate, we are craving modernist structuralism. You know, the modernist project is something that I’m glad we moved past theoretically, but in practice it doesn’t feel like we have. And the more we romanticize it the more it comes back, this specter, sort of hangs over it. I really think a lot about the specter of modernism and how that nostalgia, even things that are kind of harmless, or that I enjoy—like Mad Men—I mean it criticized that time period and it was kind of hard hitting in ways, but it still reifies and glamorizes. I mean it’s trying to be critical, but I also see a spike in people loving midcentury modern furniture, and we surround ourselves with these objects that actually are not neutral, that have an ideology behind them that I think is a little problematic. And so when I think about the collagraphs and the work I’ve done around aging women, they are trapped in a nostalgia-mire for particularly that time period where gender was a structure that was more real, or believed to be more immutable. There are a lot of people who crave a return to that. So yeah it’s frightening, it’s also really interesting, there is something about the modernist femininity. As somebody who is a femme gay person, I really enjoy performing in those clothes. I also crave some of the fashion from then. So there is a tension there where I am aware of some of the subtext and as a woman, since I’m not doing it in drag, I’m not sure if it’s subverting these things or is it just encouraging them? I remember I wore a vintage dress to a family reunion and my uncle, the same one with the beer steins was like, “You’re my favorite niece, you always dress so feminine.” I was like, “Well! That was not the message I realized I was sending.” I try to be aware of that stuff and try to think about it through my work.

JH: There is a different audience too, when you are doing it for capital A, Art, versus doing this for your personal pleasure and to go out and do whatever. The audience is going to read it differently.

GM: Right. I mean, drag culture is really powerful and I’m cis-gendered, I’m comfortable being female, but I’m sad in my soul that I was not born a man that could be a drag queen. And I know bio drag is a thing, and I could get into that scene. So surprisingly I think a lot about drag, lately. With these ceramic wigs, I’ve been thinking about them somewhere in between a wig for an aging woman and wig for a drag queen, or maybe, something that can be shared between the two. Because sometimes I see age as a kind of drag. There is just more to think about there that I’m interested in, but I like the way drag deals with nostalgia. I think it’s really effective. I do think a lot about how to make work that can be critical and borrow the imagery of these things, without just reifying or repeating the problem.

JH: This is kind of a shift, but I find there is a thread of violence in your work that is either explicit violence, harm done to a body, whether that’s human or land, or an identity or an idea, or little bit more passive. So I think about the No Dumping project, which is this terrible violence done to this land and also the most banal type of violence. And then I think about the iron etchings, the animal etchings on the irons and the evidence of this violence. But also about the violence of performing femininity and the ways in which you use humor to poke at that too. I don’t know if you also find these threads in the work.

GM: I thought about the body being present or absent, especially with the collagraph work and the wigs, these things that suggest bodies, and the irons, which are literally creatures’ bodies. It’s really interesting, the violence thing though, because it isn’t as much something that I am doing deliberately where some of the other themes that I’ve talked about I am really thinking about it consciously. But it’s nice to hear that you’re picking up on darker themes because those things are definitely there. The etched irons, I mean a lot of it is about death, one way or the other: eventually or the immediate. The etched irons are definitely and perhaps in a quite literal way about death, and how death creates objects, and how those things are then more possessions that I am struggling to throw away.

JH: Like the actual bodies of the creatures?

GM: Yeah, yeah.

JH: What else are you going to do with them?

GM: Well recently, we have a student who does taxidermy and she’s really changed my life because now I can save them in my freezer and give them to her.

JH: She’s going to do taxidermy to these dead animals?

GM: She has, yeah.

JH: And now you have your own collection, like we talked about, of dead things.

GM: Yeah, she’s currently using them in her own work, but I would like to commission her to just taxidermy them for me. Mostly it’s just a collection of shrews right now, which I like because there’s this gender undercurrent, the etymology. But yeah, I think violence is definitely there in those pieces. When I was finding those and recording each one that I found, it would be decapitation or something that was distasteful. It was also fascinating to me, making that series, how impassive my cat is about those things; it’s just such a part of his daily existence. I think we live in this aesthetic, cut off and sanitized environment, so seeing death pulls me back into remembering that I am an animal, which is something that’s always in the back of my head, but it’s bizarre to me that we spend so much time in environments that are meant to make us forget about our animal-ness, about the fact that we have bodies.

JH: We are just as gross as the cat.

GM: Yeah. It really feels like that sometimes. Encounters with death are a way to remember what’s actually happening, in terms of having a squishy body.

JH: An actual reality check.

GM: And aging to me is kind of violence on the body, too.

JH: Yeah, I wanted to get to that. Especially in the way we perform gender as a society and women in particular, the way society tells us we can and cannot age, and the way it’s kind of been challenged recently, but also in this way that is still kind of gross, and prescriptive.

GM: I want to be very age positive, I want to be very much like you can wear this with grace and beauty, but on the other hand, why do I have to wear it with grace? What if I want to age into a disgusting old crone? That’s also my right.

JH: That’s right! [laughter]

GM: More what I think about, I’m thinking about myself, so there is a narcissism element to it probably, but mostly this is from watching my mother. My mom had me when she was 40, so she is older than most moms and she has also had a little bit of harder life in some ways. I’m watching her age and it’s happening fast, and the violence that I’m seeing is not even the aesthetic element so much as it is how your body just stops cooperating.

JH: Like a betrayal.

GM: It is like a betrayal; it’s all these little deaths along the way. That is one thing that I didn’t understand when I was younger, the gradual process of aging means you are letting go of something every few years. It’s not that at the end of your life you let go of it all, it is by the time you get to the end of your life you’ve been letting go of things, you had to give up your attachment of being able to see, you had to give up your attachment of being able to hear. In a way, all those little deaths are more terrifying to me, or at least equally. And seeing it happen to my mom which once again is like watching my future mirror self go through this and seeing what she does to fight these things and the inevitably and futility of that. My mom is a steel magnolia; in many ways she is doing just great, but it’s hard not to notice how time is wounding all heals as they say, and it’s hard to watch a little bit.

JH: This makes me think about healing. I’m coming back to the series of irons again, because they’re objects that meet at the intersection of these themes I see in your work. Instead of choosing an object that is related to the task of removing a dead carcass, you pick this object that is in some ways a “healing object.” It smoothes out wrinkles and makes things better, more presentable, what have you. So, I wonder—even thinking about the prints of clothing—healing—and I don’t mean in an art therapy way—but grieving and healing is something I also see across your bodies of work.

GM: Definitely with those collagraph pieces, I mean the first ones were made to depict a specific person who had passed away. Part of the process of coming to grips with that and understanding what that meant was clearing out that person’s closet, and removing their possessions like it is for anyone when someone is gone, and you’re left to deal with their possessions. Remembering and memorializing to some degree, through those things that were left behind—I think that is the purpose of a memorial, to heal. The irons, there’s almost something tomb-like about the shape; it has kind of a memorial feel. I’m really interested in the idea of smoothing things out, ironing as an act of healing or undoing something that’s wrong. That’s really beautiful. I was also just thinking about these objects that are also so aesthetically seductive to me that no longer have a purpose. I mean they still work and some people still iron, but not with those particular irons, and thinking about material culture and our being surrounded by these things that are now insignificant or outdated and need to be disposed of but I am unwilling to dispose of. Again, it goes back to the preservation, of an unnecessary thing, and a gendered object, obviously.

JH: Some of them are so old that it’s pointing back to this specific moment in feminine performance too. This call back to modernism, the 1950s housewife who is pressing her husband’s underwear or suits or whatever they did.

GM: I like that paired with the violence of the animals on them. In the same way with the dresses—I’m clearly alluding to specific time periods and specific performance—but with the body being gone, it makes you think ghosts and it makes you think of absence.

JH: Exactly. As much as those things are there and represented, the lack of body is equally as represented in its absence.

GM: And it makes you think about loss. Memorial is also about a moment of making things more real. I think it’s hard for us to conceptualize the realness, because time is this weird waterfall constantly flowing over an edge, or whatever Eckhart Tolle said. I feel like it is a thing, a challenge, to ever be in a moment and realize a thing has happened or is happening to you. And when something like death punctuates a moment, things become slightly more real, or at least I experience the world this way.

JH: The ritual of it. This other performance or object that we can engage with to make it real.

GM: Something to point to in the continuum of time, like this happened. Which is the same thing with collectables and souvenirs. You’re saying, “I got this spoon at Niagara Falls.” I was an actual human here. I think it makes sense to think about the time span of objects, which is really just new materialism. Thinking about how objects outlive us over and over again, like hyper-objects, like Styrofoam, that will be there forever. At what point is the thing as or more important than the human narrators that are creating this story? That’s really interesting to me and it’s interesting also that we divide the built world and the natural world and the human world into these categories—I guess to understand them—when it’s such a continuum. I have a lot of possessions that I feel I can’t get rid of, because they feel to me imbued with a lived experience from someone else and from some other time. I have this sort of hippie dippie witchy hope or belief that I can understand or get a glimpse into those moments or those people by retaining possession of them. It’s all about not trying to lose things.

JH: I wanted to ask you how you think your practice has changed or evolved or transitioned since moving to the Midwest, because previously you were in Tennessee.

GM: Oh my gosh, the Midwest. I was in Appalachia making work about Appalachia and now I’m in the Midwest still thinking about Appalachia. But it has changed a lot. I’m influenced by my job—I teach at the University of Illinois—and the styles and professional practices of the professors around me definitely impact my work. I see myself becoming more sculptural. Moving away from, not being so close in proximity to my family, has been helpful for giving me a little perspective I guess. The work can be about these people and can be about generations without being literally depictions of those people. So, it’s been helpful for me to get both figurative and literal distance. But the Midwest is an interesting place; it is very culturally different. Tennessee is very conservative, obviously, in many ways. However, I deeply love Knoxville, and Chattanooga is another amazing city. There’s a sort of wearing your freakiness outside your clothes kind of thing, propping your weirdest family member on the porch and just letting people deal with it as they may. In the Midwest things are kept a little closer to the chest. It’s been interesting to figure out how to navigate that cultural shift just with living here. This is as much about the experience of being here as it is about my work. It’s interesting because people in the Midwest and Illinois are incredibly friendly, but they’re friendly in a different way. They keep the secrets secret. There is a bizarre unnecessary openness sometimes that I see, and that’s not true everywhere in Tennessee or in the South, and I don’t want to generalize, but at least for the culture that I was moving in when I was there, so I miss that a little bit.

JH: The openness?

GM: Yeah. I think from the standpoint of my work, though, it’s been beneficial to have a little more perspective on what that place is. It’s hard to see something when you’re inside it. So, I can see it a little bit more clearly now, I appreciate it in a different way. I have access to all of these different things, and being in the Midwest has not served to narrow my focus. I’m still trying to be a fiber artist, and a ceramicist, and all of these other things at the same time as being a printmaker and a performance artist.

JH: How do you engage with the Midwest art world? From Champaign-Urbana, how do you engage with Chicago or Indy, if you do, and do you find that to be a productive endeavor?

GM: Yeah, I think it’s productive when it happens. I, so far, don’t think I’ve done as much as I need to to get in. I go to a lot of shows in Chicago, but I’m not working to show in Chicago as much as I think I should. And some of that is just not being there; it doesn’t seem like 3 hours should be much of a thing, but it kind of is. I was talking to a curator with a small gallery in Chicago and they were like, “Yeah we’d like to see your work, but could you bring it to Chicago?” That is a little bit of a problem. It’s more I feel like I am casting the net really wide right now… I have a collaborator, she and I are shopping out some shows, and I’m not focusing on any one place, as much as wanting to get as much out there. Because I am the kind of person that could just make work and put it in a drawer, so I really have to make myself exhibit. I’m really good about residencies and I’m good about other aspects of it, but the showing part for me is something that I always have to be like, “Other people need to see this.” It’s something I am going to be doing either way just to get along with myself, so getting myself to show in more metropolitan areas is a thing. I have shown in a few places around Illinois, but it’s important to be a little bit more ambitious than I think I have been so far. Part of that is taking oneself seriously as a maker.

JH: What is coming down the pike for you, in terms of shows or projects?

GM: Upcoming things include my month-long Vermont Studio Center Residency, and I’m exhibiting as part of “Multiple Ones: Contemporary Perspectives in Print Media” at Lutheran College in Thousand Oaks, California from August 22 to October 23. That’s curated by Sheila Goloborotko, and will go to a different venue in 2020. My collaborator Eleanor Aldrich and I are looking towards a two-person show in Nashville in 2020, and I’ll be participating in the 2019 Terrain Biennial in Springfield.

I’m also getting excited about the possibility of curating. We have what is essentially unused gallery space in our house and my partner, fellow UIUC printmaking professor Emmy Lingscheit, and I are playing with the idea of rotating exhibitions in our house. I want to give regional artists more alternative opportunities to show, and was impressed with the work Katie Fizdale and Bert Stabler did with their Outhaus space here in Urbana before they moved. I’ve been feeling the lack of a funky local exhibition space like Outhaus and am seriously considering taking up the mantle, though theirs will be tough shoes to fill. I’m thinking about calling the space Split-level or Sidesplit… something like that.

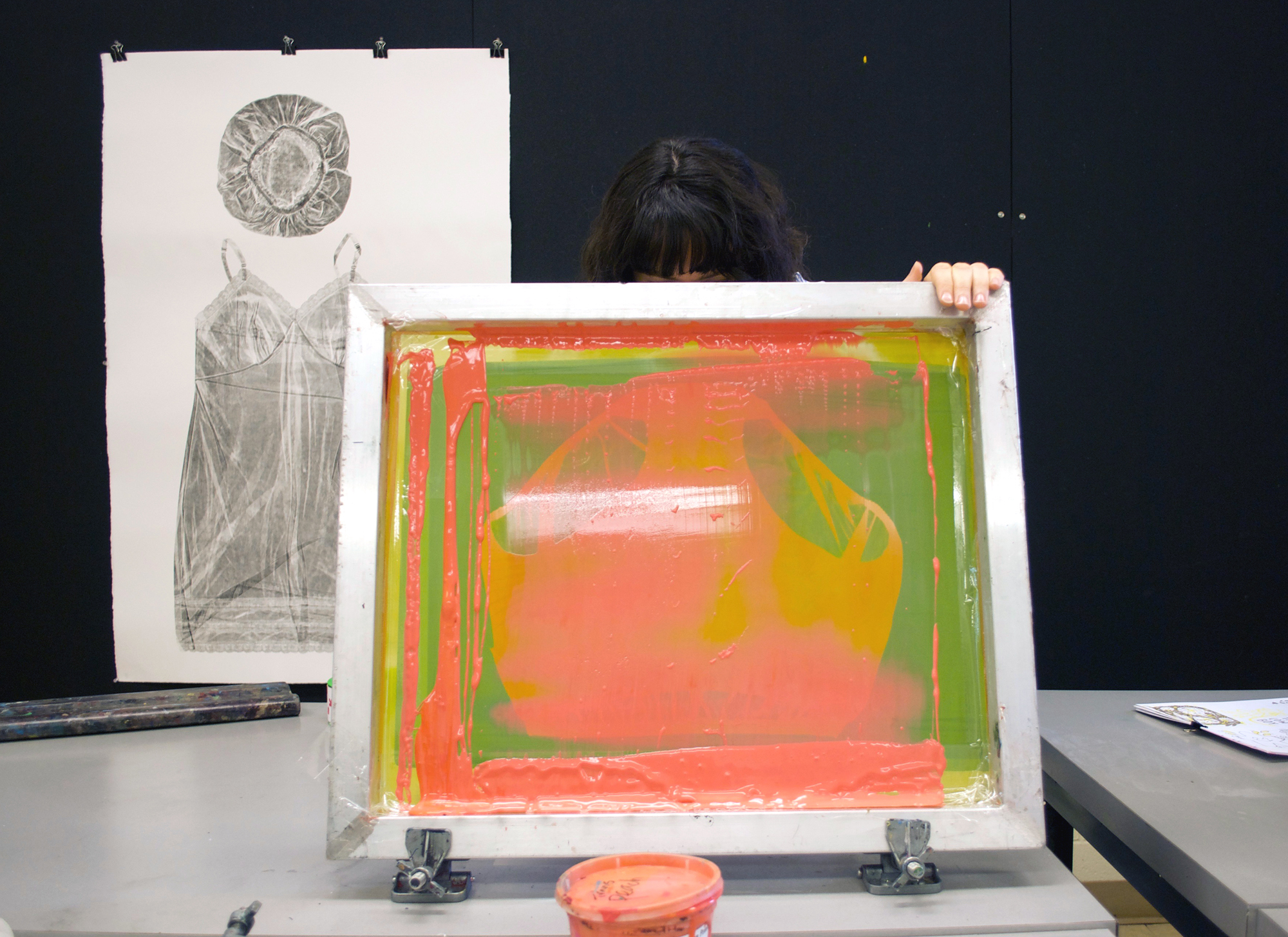

Featured Image: Guen Montgomery looks directly at the camera and smiles. In her right hand she holds a screenprinting squeegee. Pinned behind her on a black corkboard is a gray collagraph print of a woman’s shower cap and nightgown on white paper. Photo by Jessica Hammie.

Jessica Hammie is a writer based in Champaign, Illinois. She earned an MA in Art History from the University of Connecticut, where she studied hip-hop’s influence on contemporary art practices. Jessica writes about how artists visualize identities, and how arts help us understand our interconnected public and private histories. In addition to writing for Sixty, Jessica is Managing Editor and the Food & Drink Editor at Smile Politely, a Champaign-based culture magazine. She looks forward to sharing stories about artists and art communities here in Illinois and elsewhere throughout her travels. In her free time she enjoys cooking, playing tennis, and learning to read tarot.