Cynthia Oliver is a choreographer, dancer, performer, scholar, and professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She imagines, builds, and orchestrates beautifully intricate dance performances that take the audience through the breadth of the human experience. She is a Guggenheim Fellow, a Bessie Award-winner, and the recipient of a Doris Duke Award—all of which is to say, she’s highly accomplished and highly decorated.

Oliver embodies the grace and self possession of someone who has spent decades thinking about the body in space. Raised in St. Croix in the US Virgin Islands, Oliver studied dance at Adelphi University. After graduating, she danced with several different internationally-traveling companies before earning a doctorate in Performance Studies from New York University. During her time in graduate school she continued to dance, develop her own choreographic portfolio, and even spent a year as the company manager for Urban Bush Women. It’s clear that all of these experiences have informed not only her world view, but also her approach to work and play.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

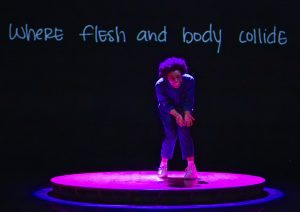

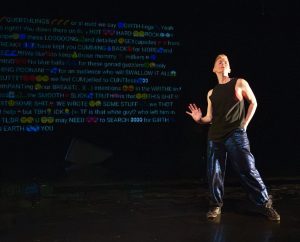

Jessica Hammie: I think the very first performance of yours that I ever saw in person was Virago-Man Dem (2017). Looking at your previous work, I’ve noticed that all your performances are completely enveloping. They are so sensorial—the sound, the colors, the music, the spoken word. I’m curious: what planted that seed in your practice, and how do you go about achieving such multifaceted pieces?

Cynthia Oliver: Whooo! Well, first of all, thank you for recognizing that, ‘cause that’s really important to me.

Growing up in the Virgin Islands, I was exposed to a lot of performance from around the world because of my mentor, Atti van den Berg. She was a Dutch performer who used to dance with Kurt Jooss, the German choreographer most notably known for his choreography of The Green Table, a political dance. That was one of my root experiences, dancing with someone who always thought about all of the environment, not just what you’re dancing, but what’s happening in the rest of the room: what are the sounds, what’s the music that’s going to what you’re dancing, what’s happening outside, who’s passing by, who’s talking in one ear while she’s looking at something else? All of that made an early impression. All the artists Atti brought to the island impacted me.

Once I came stateside, a sister-like figure, E. Tamu Bess, took me to see Urban Bush Women in collaboration with Laurie Carlos and Craig Harris at The Kitchen in New York and it blew me away. It was the first time I saw Black women’s stories held up as valuable for an audience to entertain, to contemplate, to ponder. It wasn’t all about pain and suffering; it was the complexity of Black life, and that sparked something. Tamu, unfortunately, was killed in a drive-by jacking in Los Angeles at the wrap of a film. At her memorial, I danced. I had, apparently, according to my journals [from the time], retired from dancing. Laurie Carlos said to me, “I think you retired too soon.” Not long after that, she pulled me in to do her work. And her work was very much [encompassing]. There was smell because she would cook, there was the sound, there were all these elements.

I think I’ve always been around people who have valued the entire environment, not just the one element. I want an audience to experience that. I want people to be completely engrossed in what’s happening in the space, because that’s what I want when I go to have a theatrical experience. I don’t think any one medium can do all the things that I want folks to experience. I want you to reflect on something. I want the music to propel you forward, as well as the dancers. I want the movement to say its own thing, and the language to say something that layers on top of that. I want it to be a multilayered experience. I work really hard to try to make that happen, and I do it over time.

JH: It’s definitely a multilayered experience. There’s this tension because I’m frustrated [that] I can’t take it all in. There’s no way to actually process all those things at once, but that’s what’s most exciting about it, too. Because it’s ephemeral, as an audience member, you’ll never have full access to all of that and that’s what makes it so exciting and also frustrating, in a good way.

CO: I’ve also had folks tell me it’s frustrating in a not-so-good way, because they want to be able to take all that in, and it is impossible. I like the impossibility of that. I think there are many things that are impossible that we just have to accept as what they are. For example, in Virago-Man Dem—even the structure of it, the making of it, the tools of it—I worked with impossibility. I asked the performers to think about every image of a Black man that they had ever witnessed or experienced, and that was supposed to be fodder for their improvisation. You will never come to an end. You will never resolve that, you will never get to a place where you say, “Okay yeah, I got it, I did it.” And that is really exciting to me. Even moving sections around. I built that piece in a modular sort of fashion.

I think the other thing about this is: what you see isn’t just layered research and interest, it’s a product of a really loooonnnnnggggg time in process. Even before I get to working with other people, the amount of time that I’m investigating something, thinking about it, doing the research, looking at it reflectively, reading about it, putting myself in the environment, that’s part of what then comes together so that I can make the thing as deep and rich an experience as possible.

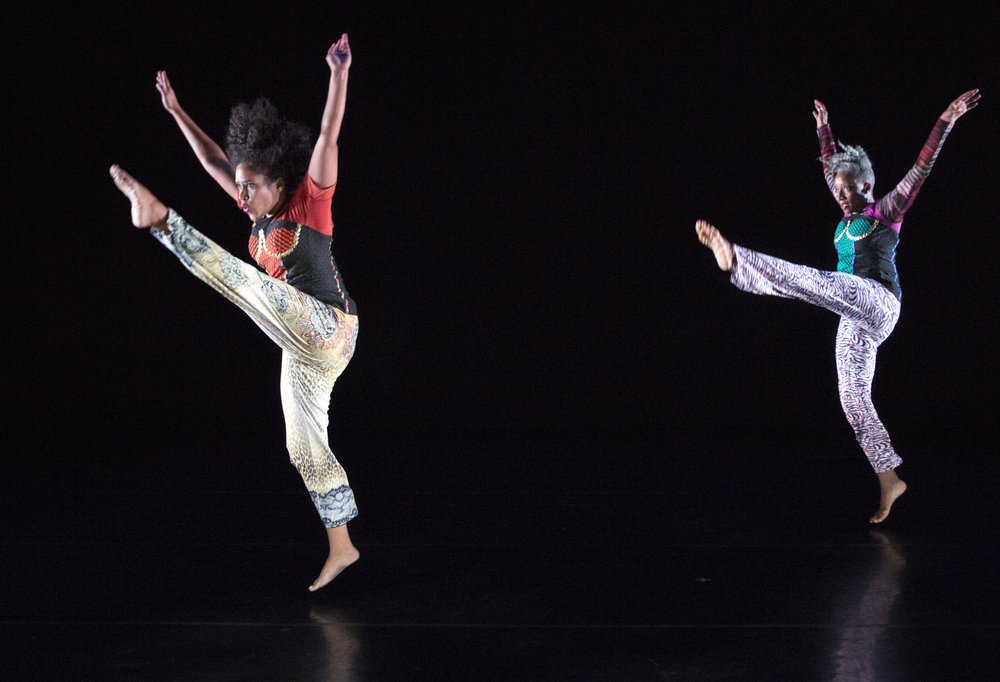

BOOM! started as a short thing where I was dealing with a certain kind of revelation about life and my philosophy about it. It was 16 minutes [and a duet with Leslie Cuyjet]. It went over like a house on fire. We were invited to make it an evening length performance, and how I decided to adapt it was different from how I might have done something choreographically at another time. I decided I didn’t want to do something we call stuffing, which is to open it up in various sections and fill it with other things, or explore more in that particular area. I thought to myself, “this kernel is perfect as it is.” I’m not saying it was perfect for the rest of the world—but it was perfect for me. It said what I wanted it to say in the time that I had. What if I left it intact and then went on? What would be necessary to say next? What would the journey look like? And because we were these two Black women who had a certain set of experiences [and] because we were also at different stages of our [lives], what are the other experiences and stages of life that we might need to… I was going to say: “commiserate [laughs] with our audience”? What did we need to communicate with our audience? That’s how I went about deciding the path of that particular work, which is very different from anything else I did. Virago is very different. Each [work] is very, very different because I choose a topic to address, and the topic then dictates the method.

JH: It seems very clear that each piece is very different; it’s not just rewriting your own work. There are clear conceptual connections between all of your work. Your work is always subverting ideas of mastery, perfection, control, and expectation through the subject matter, the visuals and the content. That is super exciting, and of course there are all the gender ties through a lot of the work, too.

CO: For years, I really just wanted to look at Black women’s worlds. I was only interested in excavating Black women’s worlds because there were so few voices there when I started. I thought it was important for me to add another to it, especially one that came from both an Afro-Caribbean and African American experience. Because they are different, pointing out some of those differences was really potent. That’s what inspired that initial curator to say, “You know I think you might want to do an evening-length work,” because I had done a short piece on a showcase evening and that piece was exactly addressing that tension between the side of me that is African American and the side of me that is Afro-Caribbean.

[I spent] many, many years looking at Black women’s worlds. Just a few years ago—it was a post-Trayvon Martin moment and, as the mother of a young, Black boy, I was just devastated. Of course, we have a long history of violence against Black people and against Black men in particular. And Black women. But there was something really potent about that moment, so I wanted to move in a different direction. It was challenging as a woman to make a piece about men, about masculinity, but I figured out a way, I think.

Failure is something that I am really interested in. What we can and can’t do. What are the limits of who we are, what we try to do as humans, what society allows us to do, and what our own imagined limits are, culturally? I love the slippage between propriety and impropriety. I love the stories that people hold on to, but that somehow slip out in fits and starts, and the stories we make apparent that we don’t even realize we’re making apparent. All that stuff, the messiness of life? I love it. I mean, I can’t say I love it in my own life [laughs]. But I love it as fodder for choreography and for building a world for all of us to live in, for a moment, to say, “Oh shit, everybody has that?” We can laugh at ourselves, or cry together, or be pensive for a moment in the quietness of the difficulty of something. I love that, and I try very hard to find that in movement, text, and sound. Sometimes it’s the right combination of all of those elements that makes that thing happen. There’s a lot of experimentation and talking in the studio, a lot of seeing where’s the common ground. A lot of propositions: I’ll make an observation and ask people to talk about their own experience of something. I love to eavesdrop in the studio. We’ll be working and then I’ll say, “Okay, let’s take a five or ten minute break,” and during that break I might be rolling around with my old ass trying to stretch, but I am also listening to the room. And the room is always rich with really interesting information: what people are saying to each other, what they are arguing about, what they might be listening to, what they might be putting on their bodies. I take note of all of that.

JH: It’s clear to me that you are a keen observer of things, of people’s quirks and idiosyncrasies. I’ve also noticed that there is humor in every piece. There’s always a point where the audience is laughing, but they’re never laughing at the performers. It is often because they see themselves reflected.

CO: As you’re talking, I was thinking about myself and Rhetta Aleong; I enlisted Rhetta to do a piece in 2000. It was the year I was invited [to the University of Illinois], and it was called SHEMAD. I was looking at madness as a vehicle to control or limit female power. We were riffing off of each other. I had this repetitive loop: she and I played gossipy old ladies talking about people in the neighborhood, or we could be mean girls in high school talking about other people in the school. It was this loop that started out with “she mad.” And it was a shhhhhhh [sound], and the “shhhhhhh” indicating, “shut up.” But at the same time, it was a precursor to “she.” “Shhhhhhhhhe mad, she mad, she bad. She mad, she bad, she mean. She mad, she bad, she mean, she clean! She mad, she bad, she mean, she clean, she dipp, she dippp, she dip, she whip. [higher pitched] She mad, she bad, she clean, she mean, she dip, she whip, [gasp] she good. She good.” And we did this ridiculous looping thing about madness, but also all these other things that she could be. We were in the corner commenting about all the people dancing their asses off on stage at the time. It was hilarious. For us, and for the audience.

JH: Even in contemporary dance, where you know that it’s not necessarily going to be a buttoned-up thing, it’s still unexpected. And it’s so humanizing, right? I think that’s something else that your work does, too. It’s about the human experience. I read an interview that you did with Bebe Miller, where you were talking about early in your career being labeled as “identity dancers.”

CO: Mmm-hmm.

JH: Because you’re Black women—you see this across the arts—where the work of Black artists is so explicitly tied to their racial identity. But no one frames the work of white artists through their racial identity. I think about dance being literally embodied. It is all identity-based. Of course that body on the stage represents a thing to everyone who is looking at them, and of course they are going to bring their own experiences of being in that body in the world onto that stage. It’s human, right?

CO: I remember someone getting really upset about that piece in particular because they thought I was making fun of madness. And I was like, “Wow, you so missed the mark.” Because finding a way to kind of accept our manias and figure out how to live with them and function with them and/or tame them, if that’s what we want to do, will help us progress in our daily lives. What was really important for me in that piece was the community, and how the women took care of each other over time. Yes, we had the mean girl thing for a moment—and it was a moment—but there was a kind of hypocrisy in it because those two people switched and became very much a part of the group and supported each other. There was this back and forth and back and forth, this flipping the script of the kind of roles that we have to play all the time. My character had this whole solo possession moment where a notion of madness then transcends the physical and moves toward the spiritual. Is it really mad, or is it divine speaking that’s happening at the same time? How do you negotiate being that channel and making sense for other people? Can that spiritual channel then inform all the other stuff that’s happening in the space, like the woman who keeps making circles and falls down, but gets up and does her practice, her routine, her engagement with other people, her singing, her whatever, again, and again? All of that was going on. And that music was bangin’.

JH: The music in your shows is always so good.

CO: Thank you. That’s Jason Finkelman— my composer, musician, husband, and collaborator—and a few other people. That year it was Jason, Geoff Gersh, and Charles Cohen, and they won a Bessie [New York Dance and Performance Award] for that show. It was awesome music.

JH: That leads me to my question about collaboration. When I look at your body of work, there are a handful of people with whom you collaborate regularly, decades-long relationships, and I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about that because it seems pretty special.

CO: I am loyal. If we do good work together, I’ma holla at you next time around. It might take me a while, and with performers—that’s the element that has changed from piece to piece. There are only a few performers who have done multiple pieces with me. But generally, on the production side, I have been loyal to the people that understand where I’m coming from, who bring their own brilliance and ideas, ‘cause I count on them for that. I am not arrogant enough to think that all of this beauty could just come from me and my ideas. I know people who are really good at what they do, who are willing collaborators, and contribute to a bigger vision, And I love that. I love sitting at the table and saying, “Okay this is what I’m thinking about,” and watching them all take notes and hear them riff on their own ideas about what could be. [high-pitched sing-song voice] It’s the most exciting thing of all!

So, Susan Becker and her costumes, oh my goodness! I love working with her because she’s willing to think out of the box and experiment. I don’t always have a whole lot of money to work with for costumes, so her creativity around that and willingness to experiment is helpful.

Jason and I have been working together from the beginning, pretty much from when we first started seeing each other. I usually start making work in silence, making the dance in silence—and he comes in and ends up saying “I don’t think you need music for this at all.” That is really important.

And then there is Amanda Ringger. We call her Mandy. Mandy is my lighting designer. I’ve worked with her since 2006. We met during one of my gigs at Aaron Davis Hall. She was their resident lighting designer. We discovered that she was also from St. Croix. It was like, “what!?” I knew she would know exactly what I meant when I would talk about twin cities [Christiansted and Frederiksted], what kind of colors I was talking about when I say I want the green flash that happens in Frederiksted at sundown. I want the color blue that’s out by Buck Island at midday on a clear day. She knows what I’m talking about.

Then there are the people who I have fallen in love with along the way and want to be a part of that process, who are also really intelligent in terms of composition and production. Val Oliveiro. She’s our stage manager and a brilliant artist. When we’re talking about the production, she will drop some knowledge on me. I like an environment where, yes, I might have to be boss lady for various things, but it’s really a collective effort and everybody’s invested and everybody wants to make this shit good. We want it to smoke.

JH: It sounds like you all complement each other in the ways that are most important and meaningful.

CO: That is cultivated over years and years and years and years. It doesn’t mean that we don’t fight or disagree. Generally we don’t really fall out. In terms of who I work with, I keep my eyes open. I go see a lot. Dancer-wise, I’ll stand by the stage door until somebody comes out, and I say, “Would you be willing to dance with me in my next project?”

JH: Well, you’re scouting, right?

CO: Always. And I’ll say, “I don’t know when it will be, it might be a few years before I call you, but I’m going to call you.”

JH: Has your approach to collaboration changed over the course of your career?

CO: I think it has blossomed into itself. In the early days, because I didn’t have that many resources, it was very limited. But as those resources grew, I could really do and be the kind of collaborative artist that I find most productive for the work.

I am not a prolific artist. I’m not one of those people who makes a new piece every year. I admire the hell out of those people. I don’t know how they do it. I don’t have that. Having an academic position is great because I can percolate for a couple of years. I can slowly think about this next thing, and then come out with it, as opposed to feeling compelled to do it because, if I don’t, I won’t have the opportunity to write the grant that will keep the institution that I’ve created alive and afloat.

JH: That’s the benefit of this type of artists-in-academia. If they’re at an institution that can support them with time, space, and often, money, or, if not actual financial support, then the prestige that might lend itself toward other financial opportunities.

CO: The space, especially during the summer, is huge. Research funds that are available to help us pay other people? Huge. There are a few places across the nation, but this is one of a few really top-tier institutions that respects the work of dance artists, and we can do really good quality work and not be mired in a lot of unnecessary administrative blah-blah. We all have ours to do, but there are some places that they have to do so much else that their careers end up really being on the back burner. It’s been hard fought, but we have managed to maintain a balance where our professional work is important and integral. This is part of why people want to come and study, because there are so many working artists here.

There’s this beautiful lineage of both alumni and faculty professionals in the dance world from Illinois.

JH: From the academy’s point of view you’re placing these people, or preparing them if you’re not directly placing them, for jobs that they’re able to get with the skills that they have presumably gained while being students here.

CO: Which is not measured in a typical way, but it’s true. If you look at this season, the past five years, the number of people who have graduated from [the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign] who are Bessie-nominated or -awarded artists, or the number of people who have gotten really prestigious grant funding [is a lot]. There’s a serious network.

JH: What initially made you consider academia or the university as a job?

CO: The University of Illinois tapped me on the shoulder and invited me out here. I came—I wouldn’t say reluctantly, but with a question mark, like, can you still have a career and do this? One of my colleagues, who was responsible for the University’s invitation, said, “absolutely.”

But the jury was out. As an independent artist in New York, I didn’t really like teaching. For me, teaching in the city was just a way for me to pay my rent. I didn’t think of it creatively. I was teaching college, but I was also teaching professionals. I would have a stint at a local studio in the city. I would teach when I was on the road as a member of the company and those were fun. But just to teach?

There were a few people who had made that leap who were models for me. David Roussève and Jawole Willa Jo Zollar, Bebe Miller. They made the move into the academy and were still really vital in their practice. I wanted to commit to paying artists. I had been burnt a number of times to the point where I had sworn to myself that I would only make a work if I could pay people. I would never be able to pay them what they’re worth, but I could pay them a decent fee. This provided an opportunity where I wouldn’t have to worry about my own living circumstances, and I could use my fundraising to really fund the art itself and the artists I wanted to employ.

And so that’s what made me think, “Hmmm, let’s try this.” My colleague Renée Wadleigh sent me a video of what the students were doing here, and it was impressive. I thought, “that could be my laboratory.” I could work, I could experiment with stuff with these really highly skilled students and take that into the field.

Independent artists never have enough time to really workshop their material. It’s gotta be successful really quickly, and it’s really difficult. There’s not a lot of space for failure in that world. You do a couple of bad pieces in a row and you could be doomed for a number of years—unless you’re certain people. There are certain people who have that benefit and are given grace: “Oh, well, it was not their best piece but we’ll see what they do next time.” That’s not the case for all of us.

This situation meant that I could possibly take care of my own life needs and make some really solid work. And I had already been validated in New York by getting critical notice [and] a New York Dance and Performance Award for my first evening-length piece. I felt like I have something to say that people want to hear or see, and this could be a good place for me to try ideas out.

So we decided to make that move—that’s me and Jason [Finkelman]. We would stick it out for three years, and if it worked, cool. If it didn’t work, we’d head back to the city. We both were scrappy people, we could make it work again.

JH: You gave yourself three years.What year is it now?

CO: Now it’s year 22.

[laughter]

JH: So it seems to have worked! Or is working, I should say.

CO: It worked! It worked. It is working. I’ve got great colleagues here and a number of additional people have been attracted to this place because of those of us who have been evidence that it can work. That you can have a viable career in the field and also have impact in the academy and in young people’s lives. I grew to love teaching. Go figure!

The students taught me, though. It wasn’t me being ingenious. [laughs]

JH: I’m curious how your experience of your own body has evolved over the course of your career. It feels really weird to be asking people about their bodies, but because dance is physical…

CO: Yeah, it’s all in the body. It’s interesting that you would ask that because as I continue to mine my own past to write this new project. At the moment, I’m seeing it as a monograph; I’m not seeing it as a dance production. I came across some stuff that I wrote a long time ago that I’m like, “Oh my god, I’ve got to perform that!” So there might be something in there.

I’m reading my cancer journals right now and in those journals I lament the years when I thought I needed something to be better or different. I was too thick, I was too this, my butt was too big, my da-da-da-da-da, it was always something. And I look back at the time, there was one particular entry, on the eve of my mastectomy, where I was mourning the body that I had that was so beautiful that I didn’t recognize, at the time, in the moment. And I swore to myself from this point forward, I am going to recognize the beauty of my body, my body has been so good to me and done so much for me. I don’t know that I’ve always held to that vow. [laughs]

JH: That’s really hard to do in this world.

CO: It’s a very hard vow! I think that I have held pretty much to that. I had a really interesting, complicated relationship with my body as I think all dancers do. I think on one hand, I knew I was bangin’, on the other hand, it was like, “Oh but if this could be a little smaller, then I could do da-da-da-da.” But, you know, I did plenty with that beautiful body.

And then, when it started to change…it wasn’t so much a visual thing, or a superficial thing, or an external thing as much as it was, “Oh wow, this requires a different kind of care.” So Bebe [Miller] and I were laughing and saying, when you’re in your teens and 20s, you can stumble into a studio and start dancing, no warm up necessary, you just hit it. In your thirties, you gotta warm up, you know, half hour, 45 minutes. In your forties, you need a full hour. In your 50s it might be more, like, two hours. After that you just roll around for as long as you possibly can until somebody says “Okay, it’s time to do something.” So, preparation has changed. And care. One of the things that this most recent award has afforded me is dedicated time to spend money to care for my body.

JH: Just to be clear, which award, because there have been several this last year?

CO: [laughs] I’ve been thinking about Doris Duke. So Doris Duke, they require you to do all kinds of things about your own financial health, and I’ve done all those things. I’m grateful for that. It was awesome. I decided that I would spend the time to do the deep, deep physical and energetic, spiritual work. I’ve always been doing spiritual work. When you then pull in the physical and connect those two? Working with your chi and working with what has deposited where in your body, and why a certain area of your body has particular issues? I’ve decided that this would be a time when I would pay attention to that in a really serious way and try to heal it. That’s what this has afforded me.

JH: You’re an athlete. Your tool is your body and you have to care for that. Even just the normal process of aging is a mind fuck. I can’t imagine adding in having a child, surviving cancer, all of that is just a lot.

CO: Yeah, it’s a lot. And you know, BOOM! came out of surviving cancer. But also addressing fundamental existential things about who we are and what we do. When you’ve shifted from having a really, seriously high functioning body to having to deal with an aging body? You know, my right hip does not want to do what it used to do. What am I gonna do about it? There are certain things I can do and other things I just have to modify. I’ve got to modify my energy. I can’t drop it like it’s hot now, unless I’m going to crawl out. There will be no getting back up, not quickly anyway!

[laughter]

JH: It is about care, right? When you’re young you feel like you’re invincible.

CO: And you are! And you are for so long. That’s the other thing about it. You’re young for so long. You think, “This is never gonna end. What’s wrong with those people stumbling around?” And then one day, it’s like, “Oh, it happens fast.” You feel one way inside and you look in the mirror and it’s like, “Ooof! [laughter] Oh, oof! Oh yeah, that’s me. [laughs] Yikes!” [laughs] You try to do what you can, but yeah, it is a major adjustment for a dancer, for an athlete to feel those changes that happen.

COVID happening and deciding, okay, I am going to shift to walking every day. And walking for many miles to keep my sanity. And a lot of that I’ve kept up. Being outdoors, being conscious and intentional about the air that you’re breathing and where you’re going and the limits of the body and what you’re going to do to try to keep it mobile.

[twists in seat]

The twist is huge. The torque. Not twerk, although that is cute, too. [laughs] That is really important to keep. Cause that is something you see go away as people age. Their willingness to…

JH: Look over their shoulder. Yeah. Noted. That’s a hot tip right there.

About the author: Jessica Hammie is a writer based in Champaign, Illinois. She is interested in the ways in which artists visualize identity, and how we come to understand our histories. In addition to writing for Sixty, Jessica is Editor-in-Chief at Smile Politely, a Champaign-based culture magazine. Drawing by Patrick Earl Hammie.