Once upon a time, Central Illinois was underwater. It was an entire shallow sea. This was more than 320 million years ago, so no one remembers; does the earth remember? This past fall, two extraordinary art exhibitions referred directly and indirectly to Illinois’ prehistoric history as a sea, connecting to the contemporary moment. Deke Weaver and Jennifer Allen’s CETACEAN, a five-night-only performance of theatrical proportions, and the Tarble Arts Center at Eastern Illinois University’s group exhibition Who Speaks for the Oceans?, use cetaceans (whales and other aquatic mammals) and the ocean as an invitation to unpack, discover, and make sense of our world as it is now.

For an elder millennial such as myself, whales were front of mind as the ur-example of endangered species. “Save the Whales” was a phrase often repeated throughout my K-12 education, and became, colloquially, in my tween brain, a shortcut for all sorts of environmental conservationist endeavors. My elementary school even ran the Voyage of the Mimi curriculum, building out weeks-long science lessons about the ocean, whales, and marine biology. So it’s perhaps with a bit of nostalgia I felt compelled toward these two projects, and interested in how they could build upon my knowledge and fear of climate change.

I entered both exhibitions with the same questions: What can art offer in times of crisis, when the average person is nearly powerless to inspire meaningful change? More specifically in the case of climate crisis and human-animal relationships, I wondered: What is our responsibility to these creatures? What is our responsibility to this planet? There are the obvious answers—these exhibitions can inspire dialogue, expose people to new ideas and new perspectives—and more elusive ones that are hard to articulate.

Sound, listening, and comprehension or illumination are potent themes through which to look at these two exhibitions. Climate change is necessarily contingent upon looking to the past to understand the present and prepare for the future; it requires a type of “listening” to the historical record, an understanding of what was being communicated, documented, and speculated by scientists, media, and artists. Reflecting upon and acknowledging the past to make sense of the present demands attention, insight, curiosity, and compassion. These traits were evident in both CETACEAN and Who Speaks for the Oceans.

Taking place at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign’s Stock Pavilion, the theatrical performance CETACEAN is an epic tale that weaves together myth, folklore, and true accounts of the known world. The cast of twelve served as dancers and park rangers, sea monster observers and narwhals, among other characters, with Weaver as the principal storyteller, a guide through the myths that ultimately led to the metaphorical bottom of the ocean.

Allen and Weaver used theater, music, dance, and visuals to create a dynamic production with various points of entry into the narrative. Some of the actors—called “rangers”—wore sailor costumes while others wore red knit caps—like the ones in Wes Anderson’s 2004 film The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, which were inspired by French naval officer and oceanographer Jacques Cousteau. The sailors carried canoes; dancers swayed in groups resembling whales’ vertical sleeping pods or underwater plants. Behind the performers were projections sharing data about oceans and cetaceans; specifically, the decibel levels in the oceans. The data revealed shipping and oil companies to be most responsible for physical and noise pollutants. One particularly illustrative sequence incorporated silhouettes of different whale species were projected, and the lengths of whales from smallest to largest were called out by several actors positioned across the massive arena, echoing through the space: “Blue whale, ninety-five feet!” At the same time, another actor would run along the bottom of the projection screen with a rope of that whale’s length, offering a visual analog to the sheer size of the creatures. As a singular human of average height, sitting in the large space of the Stock Pavilion, and imagining a fully grown blue whale—seeing a visual representation of its length, never mind its girth—was a reminder of human fragility and how small one person is when compared to some of the oldest living beings on this planet, like whales and trees.

CETACEAN was structured into two acts. In act one, two moments were particularly powerful with regard to my questions about personal and collective responsibility to this planet. First, the actors repeated the phrase, “We need to change our behavior, because otherwise we might die.” Secondly, at the end of the first act, in a callback to information about underwater ocean noise levels increasing, a caravan of honking cars and people with bullhorns circles the arena, making a truly deafening amount of noise. It was shocking, of course, but it was also an aural kick in the ass reminder that we, humans, have to change our behaviors or we will, in fact, die, and kill all sorts of other life, too. Compared to the delicacy and nuance of the performance, it was heavy handed and, in some ways, obscene, but it was exactly that juxtaposition that made the act-ending caravan incredibly powerful.

Throughout the two-and-a-half hour performance, one of the main storylines followed a dolphin (played by Weaver) that morphed into a man to impregnate women (an Amazonian myth). He made his way to the British Isles, and ultimately found himself at the bottom of the ocean to converse with Sedna, the Inuit mother of the ocean and all of marine life. Along the way we heard testimonies from early nineteenth century witnesses of the Gloucester, Massachusetts sea monster. We learned that Moby Dick’s real name is Barry in an opera serenaded by Captain Ahab. There was a personal account of visiting a beached whale in the Pacific Northwest. We were told about the ways the whale’s body had to be pierced and punctured, lest it literally explode. We saw images, projected on a large screen at the back of the stage, of families posing for photos in front of the carcass.

Weaver, as the writer of CETACEAN, carefully blends humor and horror to arrive at the intersection where those things mark humanity. We are implicated as audience members—humans who live on this planet and take, take, take. Though he doesn’t offer any prescriptive measures for fixing these problems, I left the experience feeling like my individual actions and value structures were doing something, in some small way, and that all of these tiny, individual actions work in the collective to push toward positive change.

![Image: Jenny Kendler and Andrew Bearnot, [detail] Whale Bells, 2019-ongoing, hand-blown ombré glass, miocene-era fossilized whale ear bones, cotton rope, and felt. Installation in a museum space with a frosted glass paneled wall as a backdrop. From the ceiling hang approximately fourteen ropes at the bottom of which are glass bell shapes. From the bells hang fossilized whale ears. The light is dramatic, and the bells are reflected in the shiny floor. Detailed view is a closely cropped bell, with others receding into the distance. Photo by Jessica Hammie.](https://sixtyinchesfromcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/IMG_6715-727x1024.jpg)

Who Speaks for the Oceans? (WSFTO) was originally curated by Alaina Claire Feldman, Director and Curator of Mishkin Gallery, and David Gruber, Distinguished Professor of Biology and Environmental Sciences at Baruch College, and traveled to the Tarble where it was expanded by Director and Chief Curator, Jennifer Seas. WSFTO is a group exhibition with works of differing media. As in CETACEAN, many of the works in WSFTO urge viewers to consider our (in)abilities to communicate with oceanic life and the effects of all types of human-made pollution.

Upon entering the Tarble Arts Center, viewers encounter Whale Bells, an installed sculptural experience by Jenny Kendler and Andrew Bearnot. The piece is a collection of “bells” made from blown glass and fossilized whale ear bones. They are suspended from the ceiling. The work is hauntingly beautiful; the installation is perfectly suited for the building’s entrance hall, with floor-to-ceiling panel windows acting as a frame and backlight to it. Though viewers are not permitted to ring the bells (yes, I asked), the implication is clear enough. The wall text informs viewers that the work is inspired by humpback whale song, a language humans cannot understand. The use of fossilized whale ears from an ancient whale species related to humpbacks makes a literal connection to the past. Paired with the delicate glass, the bells are inert objects that signify the eerie beauty of, and tenuous reality facing, humpbacks (and other whales) in a world where they are (according to the exhibition’s wall text) threatened by “commercial shipping noise, fossil fuel exploration, and military sonar.”

This work responds to Roger Payne’s Songs of the Humpback Whale (1970), literal recordings of humpback whales in the ocean. Songs of the Humpback Whale is a documentary relic, an artifact that cannot be replaced or remade because the conditions are no longer the same. Within the context of WSFTO, Songs of the Humpback Whale serves as the aural inverse of the silent, inert piece Whale Bells, and the basis from which we can try to measure human contributions to the oceans (mostly negatively) and animal responses to it.

Similarly inspired by Payne’s recordings, and historic attempts at human-ocean connection, Ursula Biemann’s short film Acoustic Ocean (2018) was a compelling narrative about an aquanaut conducting underwater research in an attempt to communicate with sea life. It’s beautifully shot and composed; the use of sound is particularly clever and poetic. As the aquanaut conducts tests and tries to use technology to make legible contact with the underwater world, there is music that grounds viewers to the human world, as well as other sounds that speculate about noise or communication that could come from the depths below. In an interview for the 2018 Taipei Biennial, Biemann spoke about using underwater recordings from the 1970s for this film, noting that “today the sonic pollution of the ocean is so high that you wouldn’t be able to make that sort of recording anymore.”

Sonic pollution in the ocean is something we don’t often see or hear in most media as a talking point about the ill effects of climate change—it’s certainly not as easy to visualize as wildfires and super storms—but it’s something that has massive effects on ocean life. When considering these art experiences, I keep returning to the problem of sound pollution, and how profoundly uncomfortable it must be to live in unrelenting noise. That’s a point of these works: for me, a human, to consider and empathize with an animal, something I have been socialized to believe is inferior to me, whose life is less valuable.

I enjoyed the juxtaposition of documentary materials like The Silent World (1956), the film by Jacques Cousteau and Louis Malle that followed Cousteau and his naval crew as they explored (and exploited) the Mediterranean, Persian Gulf, Red Sea, and Indian Ocean, with traditional artworks like Myrlande Constant’s sequined tapestry La Sirene et la Baleine (c. 2000; the siren and the whale). These two works were installed across from each other. It placed the mythical Mami Wata, the female water spirit often associated with fertility and good fortune, depicted here as a half-human, half-fish siren, in conversation with the very real Cousteau, a human man who tried to be like a fish (he invented the first SCUBA apparatus). Both Cousteau and Mami Wata have become signifiers of a specific type of gendered knowledge and action: women converse, men act. Mami Wata, as a religious icon, is a stand-in for mother ocean, a spirit that can offer fortune or death, and a keeper of the knowledge of the ocean. Cousteau, the “father of underwater sea exploration,” has become an icon, too, and if not a keeper then at least an excavator of knowledge of the ocean. These works in dialogue call into question viewers’ relationships to how humans have gained this knowledge, and at what human and material cost.

Much of our media and conversation about climate change is couched in the language of listening: listening to the scientists, listening to climate refugees, listening to keepers of land and sea record and reflect upon how things were and how things are. In both CETACEAN and WSFTO there is yet another plea to listen to the sounds in the ocean, to the animals therein, to the artists and scientists who worked to document the conditions of their times. At the end of CETACEAN, when the dolphin arrives at the bottom of the ocean to ask the mother for her help, the dolphin is subject to a monologue, or maybe a soliloquy, about her circumstances. We, the audience, were made to listen to her, to hear her experiences, observations, worries, and hopes. We learn that the bottom of the ocean is full of all of the garbage humans have thrown into those waters (it’s disgusting, as she notes). Will hearing these realities and seeing evidence in the form of artworks offer some different type of understanding that could lead to actionable change?

Speculative storytelling creates opportunities to imagine differently, and through those imaginings, make space for empathy. Speculation requires a basis from which to respond, and climate change has inspired a wealth of speculative media and artworks; it’s possible to create work that responds both to the current moment and previous speculations on the same topic. For example, both in CETACEAN and WSFTO, there are attempts to visualize the sound or noise or song from the oceans, to make visible that which is harder to quantify, identify, and measure.

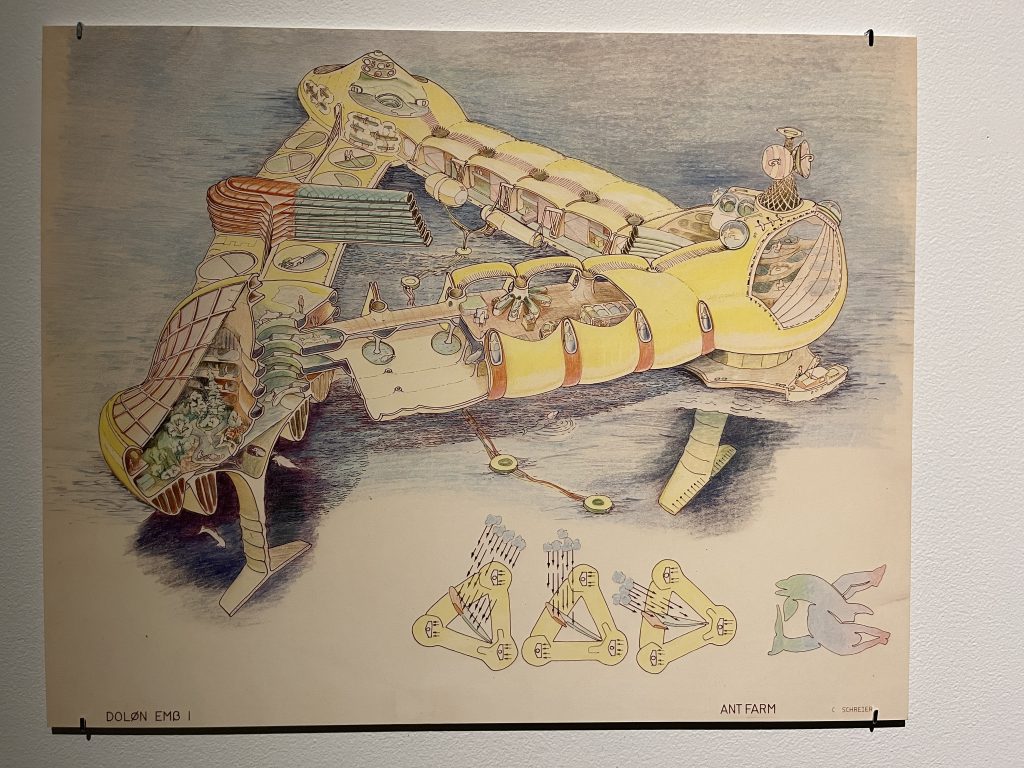

Ant Farm’s Dolphin Embassy (1974-78), the artist collective’s research project to build “democratic relations between cetaceans and humans,” is among the more delightful speculative works in WSFTO. Presented as a series of documents and proposals, with drawings, FAQs, and news articles, Dolphin Embassy attempts to follow through on the desire to form meaningful relationships with sea mammals. In this instance, the work was playful and hopeful, even inviting. It’s unclear if Biemann or Weaver were explicitly influenced by speculative works like Dolphin Embassy, but the echoes of ideas are evident in Acoustic Ocean and CETACEAN. The quirky, hopeful works of the 1970s—including Will E. Jackson Performing Live on the Phyllis Cormack (video, 1976), wherein Jackson plays synthesizer music to try to communicate with whales—would not have been possible without the foundational human-animal-ocean myths of many cultures and traditions. In this sense, the work is cyclical, endlessly reflective and hopeful, with one generation inspiring the next.

Both art experiences looked to the past to understand the present. In CETACEAN, Weaver drew upon myth and folklore to offer an origin story for how we, humans, came to be in this particular relationship with whales and, by extension, the planet. Who Speaks for the Oceans? also looked to the past, in curating fine art and documentary works from the early- and mid-twentieth century, to contextualize artist relationships to the oceanic unknown and scientific discovery aided by new technology. Both ask what we have learned, though neither offers a checklist or guide to making changes for the future, save for CETACEAN’s obvious, “We need to change our behavior, because otherwise we might die.” This is the erroneous conundrum of this moment: collectively we think we don’t know what or how to change, but in fact, we do. Even as people living in the landlocked Midwest, we live in globally connected societies, and know exactly what needs to happen in order to make change, to save the whales and the trees and the oceans and the atmosphere—and the people who live among them—but systems (capitalism, colonialism, white supremacy, patriarchy), and those who hold most of the power within those systems are not interested.

There are threads of hope in both CETACEAN and Who Speaks for the Oceans?, but in 2023, it’s challenging to hold tightly to them. Climate despair is very real, and individuals have little power to make the massive changes needed to stave off calamity. The cacophony of distress around our current climate emergency is a mirror to the noise in the oceans. In works like CETACEAN and those in WSFTO, the artists have tried to call attention to these problems by attempting to visualize them. Art allows us to engage with these difficult topics with the buffer of beauty, humor, spatial and temporal distance, and curation. These artists—Weaver, Allen, the CETACEAN actors, the artists included in WSFTO—and curators have left behind receipts. They have looked to the past, considered the present, and contemplated the future to make work that will undoubtedly be informative to the next generation. If we cannot save the whales, we can leave behind the evidence of our efforts and anguish.

* * *

CETACEAN (The Whale), the 6th performance from The Unreliable Bestiary, took place September 28 – October 2, 2023 at The Stock Pavilion (on the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign campus).

“Who Speaks for the Oceans?” is on view September 22, 2023 – January 27, 2024 at the Tarble Arts Center in Charleston, IL.

About the author: Jessica Hammie is a writer based in Champaign, Illinois. She is interested in the ways in which artists visualize identity, and how we come to understand our histories. In addition to writing for Sixty, Jessica is Editor-in-Chief at Smile Politely, a Champaign-based culture magazine. Drawing by Patrick Earl Hammie.