At the Allerton Park and Retreat Center in Monticello, IL, this year’s Spring 2022 Artists-in-Residence included Nicole Anderson-Cobb and Latrelle Bright, artists whose work fits into the framework, “Rooting a Deeper Connection.” I met the artists at the tail end of their three-week long residency, just before they hosted an invite-only “first draft” presentation of their research. As both artists are active theater makers in Champaign-Urbana, IL, their presentation was part installation, part performance, and part audience engagement event.

Allerton Park and Retreat Center, built in 1900, is a property owned and maintained by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The Monticello park is the former estate of Robert Allerton, who gifted the property to the University in 1946, with the intention of using it “as an education and research center, as a forest and wild-life and plant-life reserve, as an example of landscape gardening, and as a public park.” Allerton, the son of a very wealthy agriculturist, was a patron of the arts as well as an artist himself. In 2020, Allerton Park announced a new artist-in-residence program, which aims to “inspire the community to utilize and value nature, history, and the arts through accessible and sustainable programming, research, and facilities.”

The park is about 27 miles from the U of I campus, but it doesn’t exactly feel like it’s explicitly part of the campus community because it’s not a major site for normal academic activities. Many people in Champaign-Urbana feel further disconnected to the park because its location, Monticello, has a history as a sundown town.

My conversation with Anderson-Cobb and Bright focused on their research. As you’ll discover below, their residency was unusual in the sense that they were in residence to research the history of Allerton Park and the town in which it’s located, Monticello. Illinois was a removal state, meaning all Native Americans were forcibly resettled west of the Mississippi. Prior to the white settlement of Monticello in the early part of the 19th century, the area was occupied by the Kickapoo. Now, Monticello is a town of about 6,000 people. It’s a sundown town, and remains nearly 95% white. This information is critical to understanding what histories, stories, and opportunities have been lost and erased, and is the foundation of Anderson-Cobb’s and Bright’s project.

Lest you think this is an interview about trauma and tragedy — in many ways it is, of course — it’s also a conversation between friends who are genuinely excited about the potential of their project and collaboration, the information they are discovering, and the opportunities to share it with Monticello, the University of Illinois, and wider audiences. The three of us talked for a long time. We laughed, we lamented, and offered many nods and affirmations of concurrence. I hope you’ll find this conversation as riveting and encouraging as I did.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

* * *

Nicole Anderson-Cobb: I am a writer and researcher. I typically look at institutions as a crossroads, and use theater and history as a way of really exploring how the institution is functioning and how people of color are navigating the institution.

For the last decade or so I have found that writing plays has been a really important and well received vehicle for being able to talk about issues of race and cultural conflicts. I have found theater [to be] a vehicle for having those conversations with individuals and groups, and that led me to think about how we consider very local narratives as it relates to Illinois. I typically write about things globally and in big urban areas, but the conversation [Latrelle and I] have been having is about how little we know about the place we live and work everyday.

Latrelle Bright: I’ve been doing theater for a long time. I came to directing rather late, so I usually think of myself as a theater maker, but I [have been] referring to myself more as a storyteller because theater is one of the ways that I like to [tell stories]. I studied directing because I knew I would want to understand all of the elements — the lighting, the sound, the costumes, the props, everything — and parallel to that has been an interest in the environment. But [I wasn’t] finding a place for myself as a Black person in the conversation. The story that I often tell is going to some environmental meetings at Florida State when I was [an undergraduate] and I [was] the only Black person in the room. They don’t know what to do with me and I don’t know what to do with them, so I left. When I graduated, I just started reading. One of the first books I bought was How the Environment Works, ‘cause I was really curious.

I’ve spent probably over a decade reading about the environment, and it wasn’t until grad school that I started creating things about the environment — things that I had learned, things that I was curious about, things that I wanted to explore. There is a series of things I’ve done over the last 15 years around the environment that’s just me using theater to try to help me to understand my relationship to the natural world, my own obstacles to engaging in the natural world, my fears of it, where that comes from, and my reverence for it. What does “dominion over” mean? What does “stewarding” mean? What is my responsibility to the land? The other parallel that puts us in [Allerton] is, what claim do I have to stolen land?

Jessica Hammie: What sorts of questions and opportunities brought you two together on this project?

LB: There’s been this interest in nature that I’ve had and I’ve been witnessing Nicole’s journey [in the] Master Naturalist Program; all of the gardening and videos she did during the pandemic (which were just really beautiful metaphors for life), watching things grow and what things needed, and watching her volunteer out at Sola Gratia [a farm in Urbana, Illinois]. I think her focus is more the land, and mine has mostly been water, but they are not separate from one another, and I don’t think you can talk about this land without talking about that river or the five watersheds [Embarrass, Kaskaskia, Sangamon, Vermillion-Wabash, Wabash River Valley] in this region. So that was the first connection.

But then we get together every now and then and kind of dig deep. I mean, if you know Nicole, there’s nothing shallow there, right? If you’re going down into that soil, she’s going to reach past the roots. That’s something that’s very attractive to me, someone who thinks so deeply about the kinds of questions that we have come up with in conversation about land and about growing things. [We discuss] what Black people don’t do. Why is that? Where did it come from? And why do we believe it? Who is out there writing a new narrative, whether it be Outdoor Afro or all these Black Girl Surf Facebook groups? I think there are questions of what are the myths, why do we believe them, are they true, and what are the new stories? It’s something that I think we keep churning around.

NAC: I think GirlTrek has played a real role. [Latrelle and I] created a local chapter. Getting Black women outdoors, getting Black women moving, getting Black women to experience parks and walking seasonally — we’ve done that together as well.

The other question that we continue to grapple with is taking up space. We’ve been talking a lot about what we have, what we have the right to call our own as Central Illinoisans and as University of Illinois employees — [I’m a] four time alum. [Allerton Park] is an extension of the University of Illinois, and we’ve been thinking a lot about what that means, why there isn’t more synergy, why this place has felt off limits, or why we haven’t taken more advantage of it. If this is an extension of the University of Illinois, what more do we need to do in this space? I’m an historian by training. I’ve had this interest that has come along via theater, which is that of Indigenous-settler contact. I did that work in West Africa — that was what my dissertation was about — but more and more I was like, there is some Indigenous-settler contact that we need to look at and think about [in Illinois]. As the flagship institution of the State of Illinois, frankly, we believe that there has to be more attention to pre-conquest history. The history of Allerton is the history of settler-Native conquest, and those interactions made Allerton possible.

So this journey is about nature, but we meet at this point of intersection around nature and history. Thinking about nature and history lands us in a place where we end up in a geographical location that is stolen. We’ve talked a lot about the layers of history that exist on this very land, in that this was a piece of land that belonged to the Kickapoo. They were displaced by settlers, and it became settled land that Mr. Allerton acquired, and then it became the property of the University of Illinois. That’s a lot to talk about. It’s a lot to think about, particularly as an institution that spends so much time talking about the Chief [former racist mascot at the U of I]! Institutionally, there should be more attention. This [residency] is 25 miles from my house, but it’s a world away. It’s a universe away. That’s some of what we are digging around and thinking about.

JH: What is it like to collaborate and work with each other?

LB: Even though we’ve worked together before, this is the first time we’re creating a new thing together. Is that true?

NAC: I think so. Latrelle directed Lynn Nottage’s Sweat [at the Station Theater in Urbana]. The first weekend [of the residency] we drove in to see the last show — astonishing stage, beautiful performance, intimate and amazing actors. It was interesting to knit that into our experience. We saw Sweat on Saturday and went to the [Piatt County Historical and Genealogical Society] archives on Sunday, and listened to the archivist talk about class and labor. We talked about the relationship between Allerton and the community, and the way that Sweat deals with the factory and its impact on local people. No one could have told me in a zillion years that going to Sweat was going to have us think about what we’re learning about the relationship between Monticello and Allerton. I was going to [the show] to support Latrelle. I tell people to support anything she does because it’s always fantastic, but it really was nourishing creatively for this project as well as just seeing her do astonishing work again.

I think this [project] is the first thing we’ve created together. We’ve never lived together before, much less having lived together for three weeks. We’ve been friends and collaborated on other stuff, and this really has confirmed that we can do this.

LB: Yeah. I’m hoping that this isn’t the last collaboration, and that this has a life that continues. So how has it been to collaborate? It’s almost not been — it’s just kind of what we do. Everything just kind of blends. Even if we’re not on the same page, we’re nearby and so it still works.

NAC: One reason we wrote this proposal is because we knew one another, but also because, as two Black women coming into this context, we were really candid with [the Allerton Park residency search committee] about the fact that we needed [each other] to have each other’s back. [As two Black women in a predominantly white environment], we don’t take personal safety and policing for granted — it’s just the nature of being Black in America. If it wasn’t each other, it was going to be somebody else.

LB: I remember having a hard time wrapping my brain around what I would do for three weeks [working alone] on a piece about water. I think one of us said, “Did you hear about this [residency]?” And then somebody said, “You wanna work together?”

NAC: We were both working on separate proposals.

LB: Yeah, [and] we had to merge our ideas.

NAC: [We’ve] been kind of fusing ideas.

JH: Observing you two, it seems like a really good fit. There’s a long history of nature being connected to beauty, the sublime, and peace as much as there’s a long history of white supremacy connecting BIPOC people to the ugly, violent, and urban. How does this project function as a reclamation and reimagining of those ideas?

NAC: We’ve been talking about that particular issue, the extent to which nature and the natural world is always de-populated. I’m in a fellowship on the East Coast and it’s always interesting to me that because we inhabit predominantly white spaces. The conversation’s always about stewardship, about care for nature, about planting a thousand tulip bulbs or whatever. It’s rare to have a conversation about the fact that you’re not the first stewards. You’re not the first people to appreciate the land you’re sitting on. You’re not the first people to have built and survived and sustained this land, but there is a profound blind spot in terms of white appreciation of nature, but not of the human beings that existed on the land before they got there.

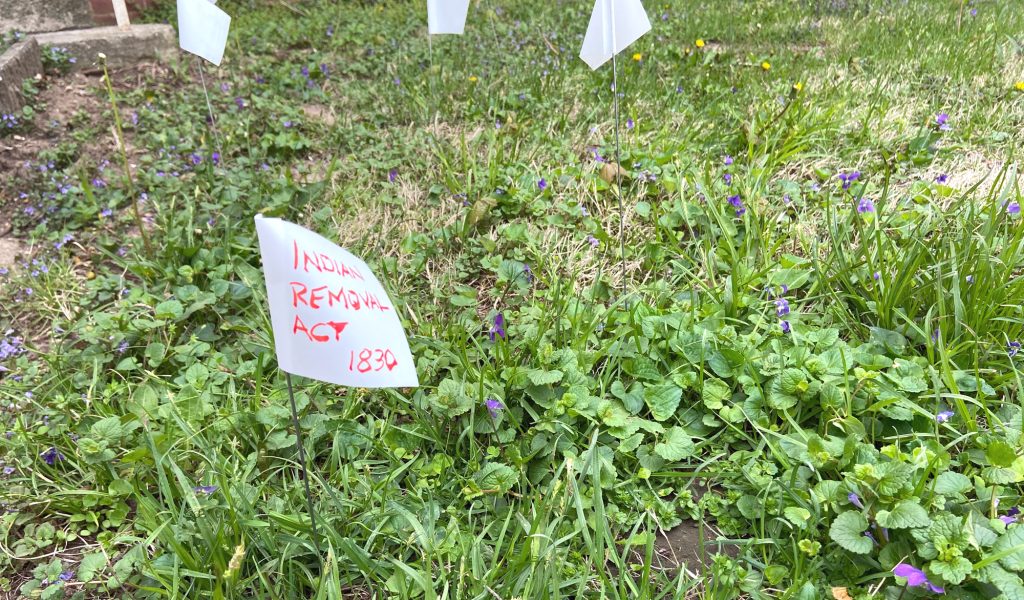

We don’t talk about the violence that was done against Native people, Native communities, the Native built environment in order for you to get your nature! In order for you to have this beautiful space of reflection and introspection, people had to be violently removed. We are sitting in a place where the Trail of Death passed through this very community. Native people were moved from Indiana, through Illinois, through Missouri, and into Kansas. So we’re very selective about the kind of violence we want to discuss.

We have a situation where it’s easy for us to pinpoint Black and Brown urban violence, but we’re not willing to talk about the historic violence that has existed in urban spaces and exurban and rural spaces, continually against people of color.

LB: Right. That’s one of the obstacles, one of the hindrances to being in nature — not only the most horrific lynching. You can’t write a poem about a tree without thinking about that history. But then there is also the free labor under duress of the actual land itself, the violence inflicted to reap all of this that is still being sown.

JH: I’ve been thinking a lot about the history of violence that is erased or obfuscated with land acknowledgements, and how they are important ways to acknowledge a portion of the history without acknowledging the violence of the acquisition, and the dispossession and the displaced. I’ve been thinking about that and the erasure of people from this area, specifically in relation to the conversations about the Chief, and this land having been occupied before white settler colonialism. So we’re always talking around Native people when talking about the Chief. This is a very long way of saying, now this land, Allerton Park, is literally named after a white man. The land is now, “Allerton,” right? Figuratively, it’s become the white man… does that make sense?

NAC: Vital observations, absolutely.

JH: [There is an] irony and lack of awareness among some people in using all these Native words and not having any relation to [the history]. There’s a violence in that type of language, right?

LB: There’s a video game called City Skylines; it’s a world building game, and I like to play it. One of the first things I recognized in it was [that] of course all of the little people are white. You build a city, the neighborhoods, and the business districts and all this other stuff. There are asset creators that created different populations of people so that I [could] have Black people [in the game]. I called one of the first cities I started making Ocala — I’m from Ocala, Florida. I was renaming streets. I had my Martin Luther King Boulevard, I had Harriet Tubman Way. You can name the people who live in the houses, so I would change the names from Ashley Davis to, you know, Cookie from around the corner. [laughs] When I built a farm, I named it after my mother, Anita Farms. I don’t think I’ve ever been anywhere where all of the businesses are named after people I know, or who look like me. So what is it to exist in a place where everything looks like you? And what is it to exist in a place where nothing does? I think that is why it’s my guilty pleasure, to be able to try and create these spaces where just the names of things makes me feel like I belong. So I offer that.

The things we name, the names that get used are often white, are often male, and often monied. I think these names are kind of a reflection of what we value. As much as Samuel Allerton cornered the market on hogs, and Isaac, Jr. had a tobacco plantation in Virginia, it feels like that’s what we revere, because that might be what we want for ourselves. There’s something in our culture (more-more-more, bigger-bigger-bigger) that lands us in this place of acceptance of, “Let’s call it Allerton.” What was it called before? I’m really curious about that. I have not found that. We might never know. Names are important. And if we don’t know the meaning behind them…

JH: There’s power in naming.

LB: What’s in a name? That’s how I’m going to tell the history of Allerton, Mayflower, to today. What’s in a name? [whispers] Allerton, Allerton, Allerton.

There’s power. When I think of how much they extracted and played games and maneuvered to build the wealth that they had? For him to give his seven year old son, what, 250 acres of land as a gift? What were the people in Monticello doing? They weren’t living high on the hog, I imagine.

NAC: Well, this brings us to some of the work that we’ve been doing. And this is about the archives. We have been in the Piatt County archives this week, and it is a revelation, [especially related to the] question of naming, but also around the question of understanding the project of Native removal and settler silence equal[ing] Allerton. ‘Cause there are settlers here.

We’ve been looking really closely at the 1800 to 1850 Piatt County records. There are settlers who established Monticello in 1837, and the Trail of Death happens in 1838. Monticello’s existence, the Trail of Death, and the growth of this city all happened before Allerton ever shows up. Piatt becomes the name of the county, but Allerton’s wealth displaces the first settlers. He’s monied and he’s from Chicago, by way of coming [from the] east. No offense to my East Coast sisters, but these are folks that came over on the Mayflower, so there’s a primacy around being from the East. There’s an erasure of settler history in putting Allerton’s history in place of their own history.

And our conversation with the archivist — shout out to the Piatt County Archives for the generosity, for the openness, for really opening up this community to us intellectually. Look[ing] at the history of Monticello you realize that their own history has been ignored in exchange for the history of Allerton. So part of this project for us — 25 miles from where we live — is about shining some light and giving some air to local narratives. And they’re not easy to deal with. There’s some challenges in perspectives and perceptions, but there is a local history that is rich, that is vibrant, and that predates Allerton. That needs to be acknowledged in this moment [when] we are nationally contesting histories all over the place, we are fussin’ and fightin’ about how to tell history, how to tell the stories of our past. The fact that two Black women can come to Monticello and develop an appreciation for both the settlers that built this community [and] the damage that’s done historically in that building, is where we can get beyond these really narrow conversations about Critical Race Theory and some of the really cavalier ways in which we’re trying to control our history.

How do you connect kids from Monticello with their history? The history has been made so exciting for us, that we want to both figure out how to connect local children to their own history, but also to go back to Champaign with that same kind of fire. We got kids who need to understand the history of Central Illinois, and so part of the work that we’re doing is trying to make the history of Central Illinois multi-vocal. It’s bigger than the University of Illinois. It’s bigger than Allerton. It’s badder, it’s braver, it is more complicated, and it is the history of communities that remain.

LB: I’m really interested in illuminating this pattern of exploitation. [I was] talking to a local person who can trace his history back to the settlers [who] settled this land, [and his family] had hundreds of acres but now only have 40 acres. The same system that displaced the Indigenous folks and gave them that land to build and build industry and “make America great” is the exact same system that’s been nibbling and taking pieces and turning them into corporate farms. That is also part of their history. In talking to this one particular person, they understand this side of it, but I’m not sure they’re looking at that side of it. How did your family get this land in the first place? It’s that system that’s doing this to you.

NAC: Just hearing her articulate that piece, the fact that that same system is now grinding folks under, it reinforces the need for critical examination of change over time. ‘Cause you can’t see it. Most stuff you can’t see when you’re in it, but in an environment where class is so profound? The project of making the white working class has allegiances to white wealth over the solidarity of people of your same class across race…

LB: Mmm-hmmm.

NAC: That’s the homework. For centuries!

LB: Yep. In lots of industries.

JH: I think that it’s true that a lot of these systems [and] patterns of exploitation come from the grand organizing principles of white supremacy and capitalism, but there’s a disconnect [from] those intellectual and academic ideas and the practical effects and implications of those practices and how those things are implemented. Working class white people who vote Republican are almost always voting against their own interests. But it becomes a matter of the things that usurp those interests, and I mean, look at Trump. It’s racism, right?

NAC: Wow, wow, wow.

JH: It is this obsession with American exceptionalism and the American dream as a white, wealth builder. Going back to what [Nicole] said about East Coast people — there is that Mayflower framework, where you have this obsession with WASPy, white wealth on the East Coast. The obsession with wealth building and having ties to the “original” Mayflower settler thing gives clout. And there’s a way to continue to tie — you see this now with Trumpism and these people who are in these militias who think they come from American Revolutionaries, or the ability to trace one’s history as far back as “true America,” whatever that means.

NAC: It is interesting, the issue of genealogy. Because where we’ve been spending time is the Piatt County Historical and Genealogical Society. And what [the Piatt County Historical & Genealogical Society] shared with us—

LB: —yes!

NAC: —is that people are not interested in settler-Native history, they’re interested in genealogical history. And that is where [the Piatt County Historical and Genealogical Society] gets the largest amount of visitors, people trying to track their origin story. In a moment where Ancestry.com is swabbing your jaw, where there is primacy around origin, in our commercial landscape, it’s got folks hustling in there. During the pandemic, when people were hunkered down, [a lot of] people started coming to the Historical Society to work, to volunteer, to serve. So this issue of where we’re from, and who we are really, it has something to do with clout, absolutely. How your family came to be here is of interest, but what’s not so much of interest is who y’all met when y’all got here.

We’re having an event next week where we’re going to share a bit of this project, but we’ve also invited local folks to come out to share their spoken word, their poetry, their writing. We’re really interested in understanding what [the community members] say about themselves, how they represent themselves, and understand their own history.

LB: One thing that came up in this conversation was [the Allerton Mansion as a] party palace. That’s what it was, the party palace.

NAC: And that’s how they reference it.

LB: What [the archivist] also alluded to was that people from the community worked at the mansion, worked in these houses, and had some stories to tell about what they saw. And if this is a really conservative area and [a] wealthy [and] somewhat openly gay man [is] flying people in and all of the things that were happening in this space? Somebody saw something, somebody heard something, and somebody went back and said, “You know what I saw? You know what I heard?” There’s not this automatic, “Oh! Allerton!” I think I was expecting that. And that’s not really what I’ve been getting from the few people that I’ve been talking to. [They are] just, like, “Yeah, Allerton.”

JH: He’s an outsider who doesn’t share their values. This is a sundown town, isn’t it? There’s that tension between erasing the history of what was before the people who got here and now this outsider coming in who is not representing their community in a way that maybe they would like.

LB: When we were trying to figure out who the African American people were in this region, [the people at the Piatt County Archives] said that they didn’t do that here, the sundown thing. So I asked them, “Is there a siren?” And he said, “Yeah, but the siren was used for all kinds of things, there’s a tornado coming, blah blah blah.” So we have two people who I’ve talked to who said that this was not technically a sundown town and that the sirens were not necessarily erected in these cities for that purpose, but they were used for that purpose in many cities. I don’t know if that’s true. But if someone is saying that and thinks it’s true, then that becomes part of the story of this place.

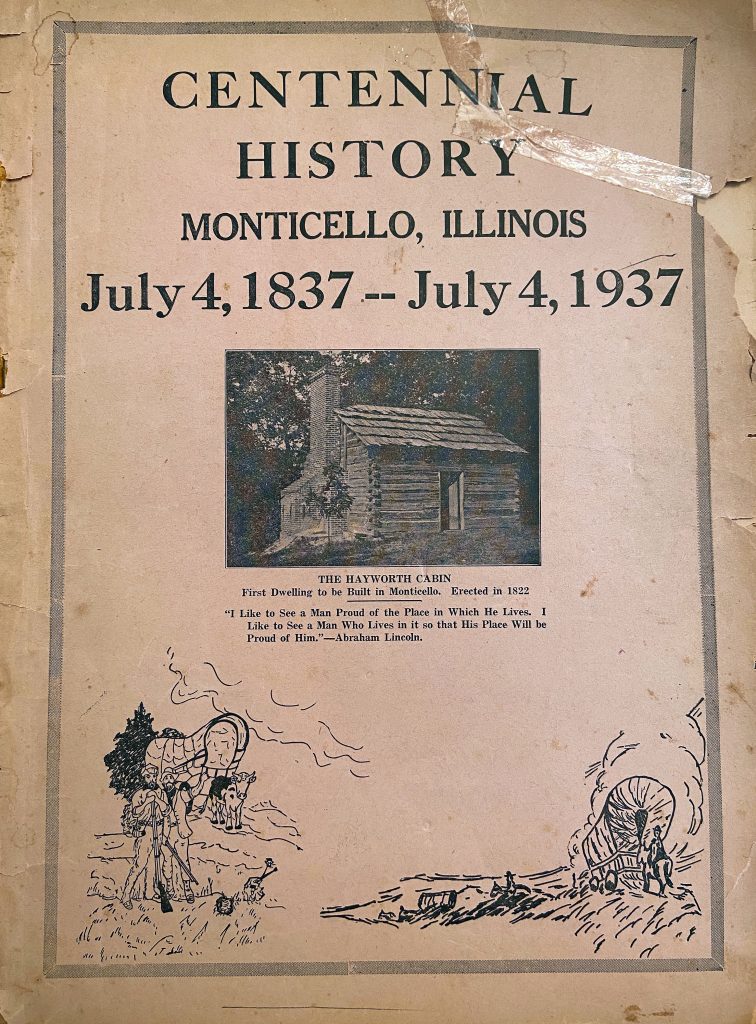

NAC: We also looked at one of the centennial documents that existed.

LB: Oh, yes!

NAC: There’s a passage that talks about some Klan organizing. At this point there’s a strong relationship between this area and Indiana. There was an exchange talking about the power of the Klan in Indiana and one comment was,”It’s just a shame that we don’t have that kind of organizing here.” This is the early 1900s, like 1927. [We were] reading in the literature that there was lament over the fact that they didn’t have a better Klan. Latrelle was like, “Who was here for you to lament that you didn’t have better Klan organizing?”

JH: That’s a really good question.

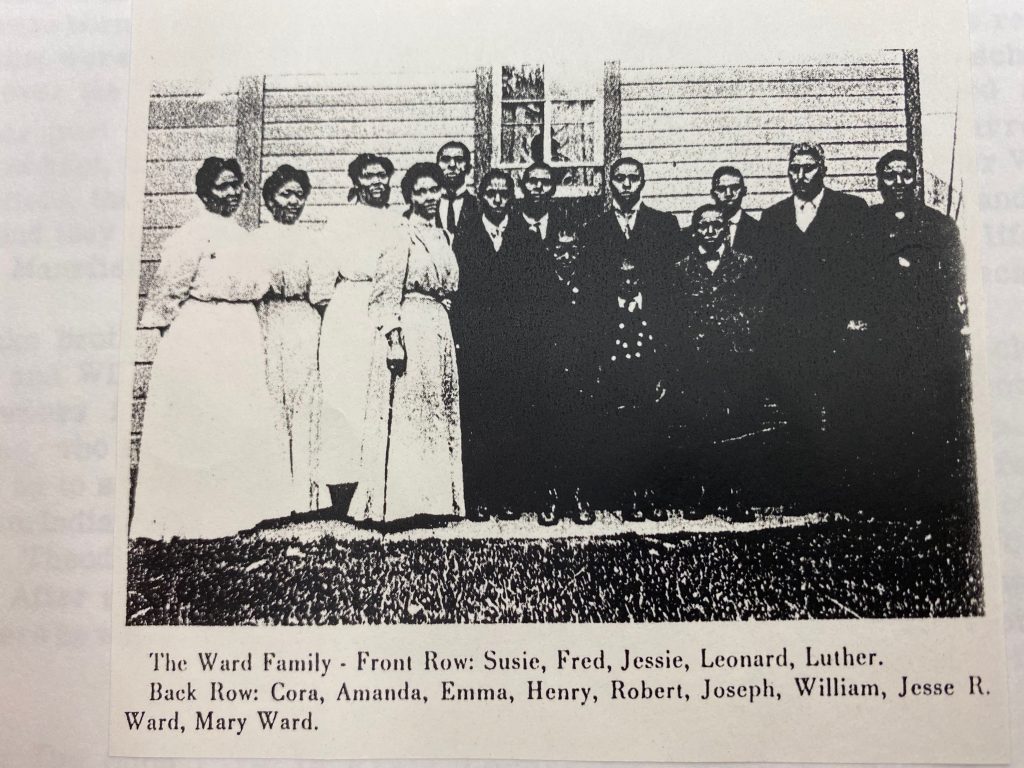

LB: Another leg of the investigation [was] to see who were the Black families around here. The Ward family [was] very well documented in these parts. The way they are talked about is that they were very upstanding. What does that mean? Sometimes that’s code for they didn’t ruffle feathers or rock boats. There’s a beautiful photograph of them.

NAC: Can you tell from the photograph their complexion?

LB: Oh yeah, they’re dark.

NAC: Oh, okay. ‘Cause sometimes “upstanding” is conflated with complexion.

LB: Ah, yes.

NAC: The work of leaving this building, going into town, sitting with folks, has been really vital. There’s been amazing generosity from folks locally. It’s another reminder that the conversation that we’re interested in having is so much broader than Allerton. We came into this open minded and open to what we were going to examine, but it’s been profound. This project obliterates the urban-rural, white-black, us-them divide, cause it’s murky in the middle. It’s extremely murky. But we’re out here in this mud together. I don’t think we expected the reception.

LB: It’s part of our armor, right?

NAC: We come at this, like, “Text me when you get to the house. Text me at night to let me know you’re okay.” There’s a way in which all of those fears and concerns…

LB: It took my mother a few days to stop texting and calling everyday. [laughter]

NAC: I’ve been to Yemen, West Africa, Europe [and] this experience was, is, and has been as new and foreign as any of those locales. Sending emails ahead to introduce yourself with the picture on the side, so we all know who’s coming, right? It’s been fascinating to do that kind of field work. To do field work in your own state, in your own neighborhood. It’s been a really, really, great experience. We’ve had a lot of things just open up to us, and also fall away from us. Just in a week and a half.

LB: I always think I’m going to talk more about nature. I always think I’m going to talk more about water. I’m still trying to make space for just a piece about the Sangamon river. But even as I say that, I can’t write that piece about the river without thinking about what happened in that river, who lived by that river, who was displaced from that river that fed them.

JH: Maybe this seems obvious, but nature is about people, right? I think sometimes there’s a disconnect when we try to fix nature or address climate change and engage with it as if it is in a vacuum. And that’s just not how it is.

LB: This is the thing that has shifted for me. The very first piece I made about the environment, I was deliberate: it’s not going to be about race, it’s not going to be about going down river, up river. There’s not going to be any of that. And I haven’t returned to that piece since 2014 because it’s not complete. My thinking has been, “Oh how wonderful it is for Walt Whitman to just write a poem about his walk on this path, on this beautiful day.” I think I’ve shifted: maybe what I’m really wanting is for white people to consider the history. And what is it that they can just see a river? Why don’t they see what I see, why don’t they think what I think? Why is what is conjured up for me is not conjured up for them, or they suppress it, or they really just don’t even think about it. What is that?

JH: Privilege?

LB: Privilege.

NAC: When you don’t experience restraint or constraint then you’re free to roam! You are in possession of everything. I think the more marginalized you are, the more time you spend trying to figure out where the boundary is. One of the things [Latrelle and I] did [was] request name tags with an Allerton logo, because I’ve had enough experiences. I had experiences on college campuses as a teaching professor, being followed by police to my office.

We have put the pieces in place for this stay. When you don’t live a life like that, you can think about the river. You ain’t got nothing else to think about! You don’t have to think about all of the consequences for a misstep.

LB: We call those our freedom papers.

[laughter]

LB: I wore mine to the County Market, just in case. I’ve also had moments of fear out here, too. The one that I’ve shared with [Nicole] is [when I was] walking on a trail. It was still light outside, and [I heard] a big F850 truck, vroom, vroom. Just that sound, Jess, just that sound. I had to quicken my steps and get back because I had this whole narrative of what was going to happen. Right now, because the leaves aren’t on the trees, they can see me from the road. They see that I’m Black. They know where I’m headed if they know this trail. I had this whole narrative of the things that could possibly happen. None of it happened, but it almost doesn’t even matter whether or not it happened. The fact that in the year 2022 in Monticello, I hear a vroom, vroom, and I’m alone on a trail in the woods outside? That’s history.

JH: That’s horrifying. Even if it didn’t happen — and thank God it didn’t — the fact that you had to play out those scenarios and physically manage your adrenaline and that stress response is traumatic.

LB: Mmm-hmm.

JH: What do you think about the idea of nature as a site of horror or terror?

NAC: We take a good number of steps to try to be mindful. I think that’s why I don’t have a problem thinking about nature and context, and Latrelle doesn’t either, because we can’t afford to. That’s why my contribution has been to do a [photo] collage [on social media] every now and again, for proof of life. This work is about us getting outside of our comfort zones in many ways. It’s also about making this place possible for other people.

Every day of welcome provides an opportunity for someone else — women, other people of color — to consider applying, consider taking your family somewhere, consider taking up space somewhere. I have [gone] back to [Champaign] a number of times, [and] it’s been interesting having people say, “I really appreciate your posts,” or, “you’re back and forth! What are you doing? You’re supposed to be at Allerton.” People are really paying attention. It is a beautiful thing to have our community walk with us. And we articulate to a lot of different communities. To have the opportunity to not just have our own experience, but to also to make that experience available as artists, as creative women, as educators, and as people, at this halfway point, it’s been quite valuable.

LB: I think I will also add that that’s not my only experience on the trail. I was there earlier this week, and there were a couple of moms with their kids, and their kids were going off the beaten trail. One of the little girls — she must have been six or seven — said, “Hi, person!” And then they all said, “Hi, person!”[laughs] That was just really sweet.

Also, this is one of those towns where you drive by a person and you wave. I haven’t done that since I was in Florida, in Ocala, where you just wave. I’ve always said that I really think I’m a small town person, but I just don’t know if I could ever live in a small town because it’s not diverse enough for me.

JH: How are you sharing your research? How is it going to manifest? I know you have a performance on Sunday, right? How do you present the research?

LB: One thing that happens on campus that I’m grappling with, something I’m writing a piece about [and] will perform out there on that front lawn, is this new practice of land acknowledgement before an event, [and] have a personal reflection on it, so that you don’t just recite it. Part of that grappling is what I’m doing with this particular piece, where I looked up the definition of the word settle. [In] the dictionary, [there are] so many layered and varied meanings. That’s what I’m trying to work with, thinking of that word settle, and all of the ways it manifests itself and my relationship to land that was taken.

NAC: There is pretty abundant literature on the Trail of Death. There’s a good amount of information, DVDs, and catalogs of the pilgrimage — there’s a pilgrimage that goes through here every five years, chronicling the Trail of Death. Descendants of the Potawatomi come back through here.

JH: I’ve never heard of that.

NAC: It’s something that we came across when we were working on the proposal, and it was part of what we pitched [to] Allerton in terms of why this project was viable. Every five years, the Potawatomi have a reenactment starting in Indiana along the pilgrimage trail.

LB: Each of the states have [created] official markers of where they stayed the night or of who died there.

NAC: But when you talk to the archivist about the local history [pertaining to the Trail of Death], the position is, “Well, people were already gone. There weren’t Native people here.” And so we wonder a lot about the absences. Paying attention to the absences in terms of what people show you, and what people make available to you, and all of the questions that get raised around what’s missing — what’s missing in terms of material culture and what’s missing in terms of peoples’ stories.

JH: So will that be in a piece?

LB: Eventually. One thing that became clear to us [in] talking to the Allerton folks before the residency, [is that] they want something public-facing, but it doesn’t have to be now. They recognize that, especially for a theater piece, we might need some time, and so there are talks about something more public in the fall, which would give us time to put something together.

NAC: Our attitude is that we want public facing opportunities, and we’ll continue to look for them.

JH: It seems like so much of this residency is about research. In the collective imagination, [for] most residencies you already have the project, and you’re just having the time and space to do the project. This is so rich with opportunity for research and for that critical rereading and understanding of local histories that to make something and present it as the be-all-end-all feels irresponsible. It needs to live. I love the idea that you’re here in this place, doing research about this specific place — Monticello, Allerton Park — are are able to go back to Champaign, even if it’s only 25 miles away, to let it breathe and also reflect on how those tendrils, those roots, extend into nearby communities.

I was thinking about this erroneous narrative of Black Indigenous People of Color in the US being somehow disconnected from place, yet assigned to specific spaces. I’m thinking about how Central Illinois was once a home to Native Americans, and we don’t imagine them in this place anymore because there are no populations, [though] there are individuals. We think the space that Native people in the US now are associated with are reservations, right?

LB: I think, personally, there’s another side to that — [to be] assigned a particular space. I think the assigning of spaces is not just an assigning of spaces, it’s a making of other spaces hostile environments to anything outside of this homogeneous [space]. And so by way of making this this, I am assigned these other spaces that as not that.

JH: It goes back to what we were talking about with the implication of the sundown town not needing the siren.

NAC: I think the very fact that we’re here obliterates the kind of duality of where you’re allowed and where you’re expected. This whole experience just blows that up.

LB: I will say, this feels like my house now. There’s no way I can come out here, having a history of this experience in this house for three weeks and not say, “That’s my house, I belong there.” That trail, almost everyday I walk down to the Sangamon River. Sometimes it’s raining, sometimes it’s too muddy, but that trail, that trail is my trail. I know that trail. And that’s part of what I think [is] taking ownership and taking up space. This is mine, too. This belongs to all of us, including this Black body. And to walk out on it, confidently knowing where I’m going, confidently knowing how long it’s going to take me to get to the river, that coming around the loop it’s going to be muddy as hell on the other side if it’s been raining.

Some people have said, “Oh my God, you’re brave!” Am I? Some people have said, “This is an act of faith.” That, I do believe. [laughs] [Nicole] said the other day [that] we are paving the way for others to feel comfortable here by showing our comfort here.

NAC: For me, our history in this country is about progress and retrenchment. It’s about making some space and then being pushed back. There is value in the path everyday, but there is also value in telling the Ward’s story. Right? There is value in the history of the Wards made visible. The reason why it’s interesting that Allerton has come to us about doing something else in the fall, or the reason why we’re having a photographer come to document what we’re doing [is] because we want inroads. [Inroads] can be breadcrumbs without sustained effort. But as Illinoisans, as Central Illinoisans, as employees, as taxpayers, this is the land that represents many things. It may now be the University of Illinois’, but that also means it’s ours as Illinoisans. So we got dibs. [laughter]

And so we gotta call dibs and keep our foot in the door. That’s why it has to be sustained, that’s why there has to be a record of it. [We are figuring out] how not to be erased.

Jessica Hammie is a writer based in Champaign, Illinois. She is interested in the ways in which artists visualize identity, and how we come to understand our histories. In addition to writing for Sixty, Jessica is a Managing Editor at Smile Politely, a Champaign-based culture magazine.