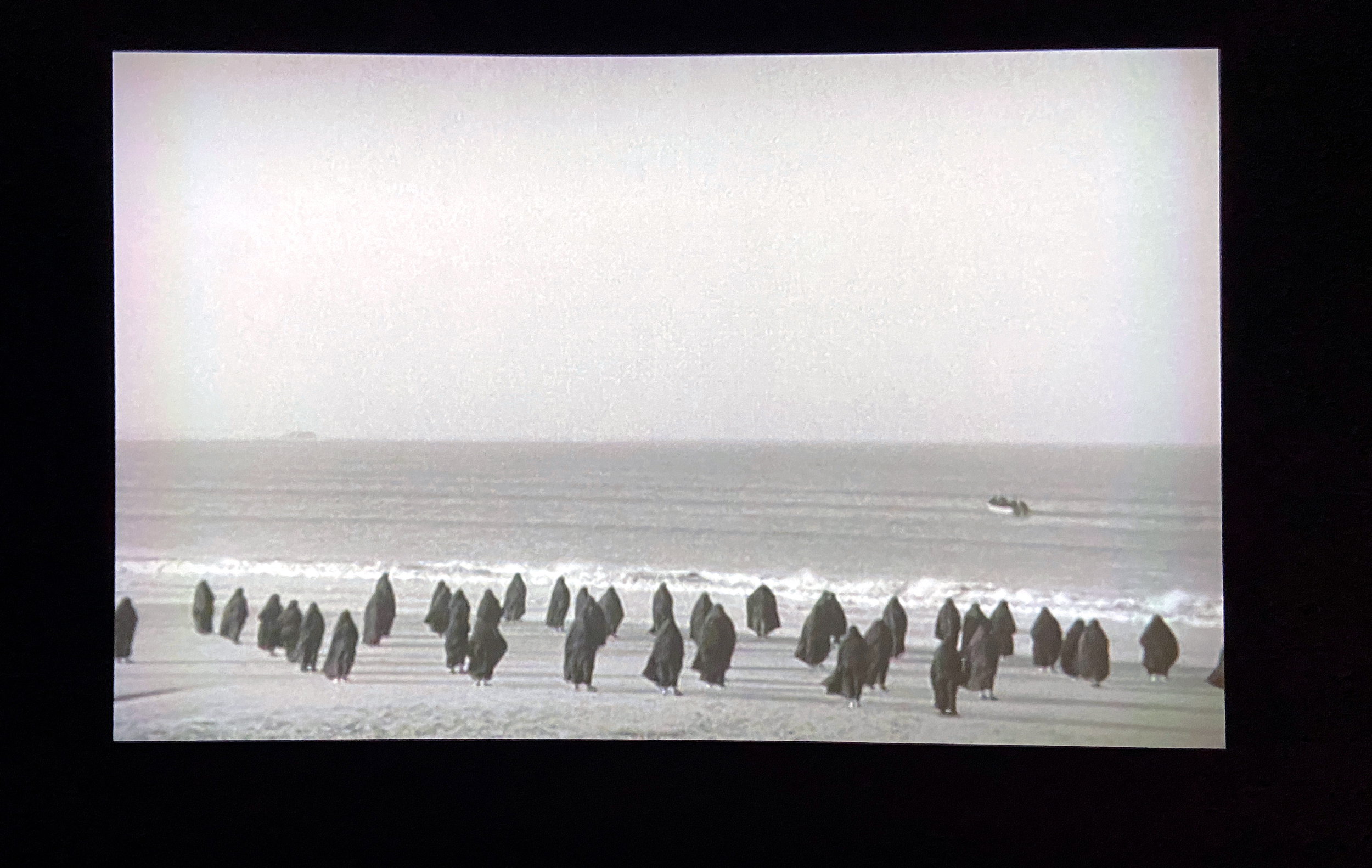

Featured image: Shirin Neshat, Rapture (still), 1999, two-channel video installation, 16mm black and white film transferred to video. A photograph of a video projection on a black wall. A small motorboat holds at least four women, all wearing black chadors. The boat is on sea or a large body of mostly still water. Small waves crash at the shore. Many other women, all wearing black chadors, stand on the beach looking out toward the sea. Photo by Jessica Hammie.

Author, professor, and astute observer of society Roxane Gay recently tweeted “Sometimes, when I return to the places I’ve lived/worked I truly wonder how I got through.” She sent this tweet the day before she arrived in Champaign-Urbana, ahead of two events that were part of the University of Illinois Humanities Research Institute and Creative Writing Program’s Festival of Writers. Gay taught at Eastern Illinois University (EIU) in Charleston, just an hour south of C-U from 2010 to 2014. As a transplant to Champaign-Urbana, I read her tweet as a sentiment speaking to the way that Central Illinois—rural Illinois—can be geographically, culturally, and socially isolating, especially for people whose identities intersect with marginalization, like Gay’s.

EIU is a small school, with just under 5,000 students in a small town of about 20,000 people. Politically speaking, it’s a tiny light blue dot in a sea of deep, dark red. It’s a university town, but it’s not exactly robust in opportunities for cultural engagement, save for the Tarble Arts Center at EIU. The Tarble is a gem due to the incredible work of curator Jennifer Seas and the curatorial team who are punching above their weight in the quality of exhibitions on view. Force Majeure, which closed December 4th, was an exhibition of video work by six women artists: Hannah Black, micha cárdenas, Shirin Neshat, Pipilotti Rist, Janaina Tschäpe, and Carrie Mae Weems. According to the exhibition statement, the show “traces the history of video and technology as media that amplified the voices of feminist discourse from second- to third- and fourth-wave aesthetics and strategies.” The work spans about 30 years, beginning with Rist’s late-1980s and early-1990s, to cádenas’ 2018 augmented reality “video game” sin sol / no sun. Aesthetically, the exhibition ranged from gritty to cinematic, showing off the possibilities of the medium.

Women and historically excluded people have always been on the cusp of new media and new technologies in art. What else is one to do when (white) men have the audacity to declare entire modes of making and material dead, ignoring the gaping absences of those not represented? One thing that was so compelling about Force Majeure is that because the works date back to the late 1980s, you can see the development of the technology in addition to the evolution of thinking about feminism(s). A unifying theme of the exhibition is absurdity in the face of extreme inequity, distress, and mistreatment. It’s the type of absurdity that begets laughter, because what else can you do when faced with such heavy, mortally important issues over which you have little control?

Pipilotti Rist’s works from the late 1980s and early 1990s now look almost nostalgic. In (Enlastungen) Pipilottis Fehler (Absolutions) Pipilotti’s Mistakes, the heavy tracking and cut-and-paste editing of the film creates a vibrant-yet-grainy aesthetic; pair that with punchy music, and it’s a whole vibe that recalls 90s TV sitcom opening credits. In works like Als der Bruder meiner Mutter geboren wurde, dufte es nach wilden Birnenblüten vor dem braungebrannten Sims [When my mother’s brother was born, there was a smell of wild pear blossoms in front of the suntanned ledge] (1992), Rist utilizes the material to underscore the subject, using the cutting and slicing of tape to mirror the cutting and slicing of childbirth. The work of birthing creative projects and human beings is made to look violent yet easy, and also incredibly labored and corporeal. In both videos, there are connections made to femininity, womanhood, and nature. After watching, I was thinking about the ease with which the body can be altered—not unlike the earth—and the ease with which they can both be destroyed. What does it mean to be ruined, and who does the ruining? These feel like outdated questions in the year 2021, but our society still asks them and holds women responsible for their own “destruction(s).”

My college semesters of German are long behind me, so I couldn’t follow the language in Rist’s videos. Nevertheless, the imagery communicated what I needed to know, to feel. It’s cliché and a bit romantic, but that is exactly the power of visual culture. It transcends spoken language to tap into the way specificity can be universal.

The Tarble’s gallery space is cavernous, with beautiful glossy concrete floors. For this exhibition, the lights were low, and each artist had their own dedicated space. Collectively, the videos were played on a loop, creating an hour or so long playlist. A couple of videos played simultaneously, so if I wanted to see everything (I did), I needed to wait until they looped around again. The practicality of this required me to spend more time in the space with the work. That time created an opportunity to reflect on the work, fortunately, the low lights and plentiful seating provided rest areas for contemplation. That time for reflection allowed me to connect the things I saw and heard with my thoughts. For me, that type of processing is unique to video; the way I think about and engage with static objects is much different.

Shirin Neshat’s space featured the only two-channel installation, with the projections across from one another. Turbulent (1998) and Rapture (1999) both visualize the recurring theme of duality. She chooses to echo the binary and duality of our lived experiences with the two-channel projections both in the black and white video, with one projection showing men and their movements and one video showing women and their movements. Together the works question the inevitability of two natures that are not wholly dissimilar. The binary is underscored time and again in the material and the content. Turbulent and Rapture are about watching and being watched, evident in both the subjects of the videos and the audience’s engagement with the videos.

In Turbulent, one projection shows a man in an auditorium singing, with his back to an audience of men. The auditorium is not full; the men wear white shirts and are seated toward the front. The camera zooms in on the performer’s face, creating a close crop and shallow background behind him. While he is performing, the second channel shows the silhouette of a woman similarly closely cropped, from the waist up. Once the man has completed his performance, he is received with applause, and then his video becomes quiet. Across the gallery space, the woman then gives her performance to an empty auditorium, and unlike the video of the man’s performance, the camera moves around her, creating loops and circles, intensifying her performance. Despite the lack of audience, her performance is more dynamic, engaging, and haunting than the man’s.

Neshat is a master of marrying image and sound to create an engrossing narrative. In her second projection, Rapture, chanting and drumming crescendo with the movement of the groups of men and the women through their respective spaces. Men move through architecture, and women move through the landscape. This rhythm is repeated in the use of the grayscale on the screen, with men in white, women in black, and the landscape in various shades of gray. By drawing upon Islamic traditions in her native Iran and the fallout from the Islamic Revolution in 1979, Neshat’s videos underscore the social manufacturing of behavior and gender norms and dynamics. Both these videos consider that specific history, but they also beg the question: What is sacred space, and how does that shift for audience and participant?

Toward the end of Rapture, a handful of women board a small motorboat and take off into the sea. I’ve seen this video many times, but this time felt different. I’m not sure why, perhaps it’s age or wisdom—or most likely fatigue—but this time when I watched that moment play out on screen I was jealous of their escape. This world, our societies, are universally misogynistic and sexist. Patriarchal, white supremacist systems continue to oppress globally. I’m tired of it all, and watching those women escape into the horizon I thought, “Good for them.” What woman hasn’t fantasized about boarding a boat and getting the fuck out?

So much of the work in this exhibition addresses the absurdity and exasperation of being a woman in this world. From Janaina Tschäpe’s woman spinning out of control until collapse, or Rist’s woman falling to the ground in intervals, or Hannah Black’s audio supercut of songs by women singing the words “my body,” this collection of videos speaks to the universality of womanhood through the specificity of each artist’s personal, cultural, racial, geographic, and ethnic experiences.

Carrie Mae Weems’ piece, I Look At Women (2017), is an illustrated spoken word poem that honors women—specifically Black women. In it, Weems says:

“I look at women. I look at them carefully. I look at them and I construct visual stories about our lives as women, as artists. I look at women in troubled spaces, in the troubled space of desire, their unrequited love, their identity shattered and whole. I listen and I see the sounds made. I imagine the visual elements. It’s an open territory, one with many doors, some leading to paths that dissipate to women here and there, who on the journey lost their way home, or who became exhausted by the effort, or who fail to understand the true price of the ticket and the related consequences, or who mismeasured themselves, others, and the situation at hand, or have been refused and denied or mistreated, or who have been driven if not out, certainly mad. Together, we look into a past that binds us into a history composed of memories, acts, and deeds, a history often written by others, a history that has left little room for the likes of her. And so she invents. She carves a space for herself in a world dominated by men…”

As the video continues to suggest, women are connected to this historical struggle, through a shared psychic and cultural connection. These experiences are passed down through generations and shared among communities. In this work, Black women who are often “refused and denied,” are given space. Weems has carved out the space for herself, these women, and us, the viewers, for honor and reverence, and acknowledgment of these efforts.

micha cárdenas’ sin sol / no sun (2018) is an experience of augmented reality. Using an iPad, players meet Aura, a trans-Latinx artificial intelligence hologram, and Roja, her cute pup. Roja leads players on a journey (from oxygen capsule to oxygen capsule) to hear Aura’s story of loss and environmental collapse through poetry. Through it all, players have an opportunity to engage with the idea of intersectionality too, as the exhibition text notes, discover/commiserate/understand how climate change “disproportionately affects immigrants, trans people, people of color, and disabled people.” The game is also available as an app for your phone ($2.99), so you can play it yourself. sin sol / no sun’s narrative is compelling and tragic, and despite the lack of “action” in the game, it’s a reminder of the power the player has to make some difference in their own lives and the lives of the people they encounter. As the newest work in the exhibition, it poetically ties together the themes present in the rest of the work on view: of femininity and nature, of sexuality and gender expression, of futility and perseverance. Aura is a literal avatar for the idea that womanness is not confined to the body, but is instead a conglomeration of socialized and cultured experiences. Formally, sin sol / no sun just about as far as you can push video and film right now, and it’s a nice bookend to the video playlist.

Force Majeure is worthy of any big city museum’s programming, making it all the more impressive that it was on view in rural Illinois. It’s the epitome of what academic art centers can offer: world-class artwork accessible for teaching and viewing, for engaging in myriad ways. It might very well be the first time some students have encountered art, video art, and/or artwork by internationally renowned women. An exhibition like this has the power to change the way a young person sees the world and themselves in it, potentially inspiring a career as an artist and thinker. It has the power for someone to see their own experiences reflected to them or invoke empathy for those who don’t.

There are quite a few academic art spaces within a couple-hour radius from Champaign. Just this semester, fall 2021, University of Illinois Springfield’s Visual Arts Gallery mounted solo exhibitions from José Guadalupe Garza and Betsy Dollar; Purdue University’s Galleries just closed an exhibition of new work from Delita Martin; Illinois State University’s University Galleries exhibited solo shows by T.J. Dedeaux-Norris and Caroline Kent—these academic art spaces and their curators are doing interesting and meaningful work. The needs and demands of an academic art space are different from commercial galleries or even non-profit art spaces, but the quality of artists and artwork and ideas is just as high, if not sometimes even better. It’s critical to keep funding public universities and the humanities, specifically these types of art spaces.

Presenting an exhibition of videos that explores the intellectual complexity of feminism as a theoretical framework is ambitious. The Tarble has put together a website of resources to further explore the themes in the exhibition. (It’s mostly for students and professors, but still, an excellent resource for the general public; your public library should be able to provide access to many of these titles.) Through the use and curation of video, Seas and the artists ask viewers to listen, spend time, and give attention to the research of these women. On one hand, it’s easy to dismiss the ubiquity of women’s bodies in our visual spaces, but on the other, it’s exactly that ubiquity that begs interrogation. Thoughtful viewers of Force Majeure are engaging with the concepts and development of feminism as an organizing principle to consider who has access and the tools to declare oneself, to take up space, to engage with the development of oneself. Perhaps the most provocative question the exhibition asks is who has the platform to express that voice?

Jessica Hammie is a writer based in Champaign, Illinois. She is interested in the ways in which artists visualize identity, and how we come to understand our histories. In addition to writing for Sixty, Jessica is a Managing Editor at Smile Politely, a Champaign-based culture magazine.