Learning and Making invites teachers, students, artists, and people who are all three at once to explore the radical possibilities that exist at the intersection of making and learning. Learning is the act of deepening human experience and increasing human agency. Many artists work as educators and consider this work as part of their practice. Arts programs in and out of schools foster intergenerational communities that not only generate critical contemporary art but act as laboratories for radical experiments in power, care, and collaboration.

The Reparations for the Earth Curriculum, created by the Young Cultural Stewards team at the Park District, offers strategies for sowing seeds of creativity and collective power that transcend discipline. Over Zoom, I spoke with the two program stewards, Irina Zadov and Najee Zaid-Searcy, and Teaching Artist, Juliet Montelongo to better understand the foundations of their collective practice. Our conversation touched on returning to art as an experience of personal healing, putting reparations into practice, learning from nature, and the nuances of flocking.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Grace Needlman (they/she): Please introduce yourselves and a bit about your individual practices as artists and educators.

Juliet Montelongo (she/her): I grew up in CPS, in Pilsen and Little Village. I am currently a Young Cultural Stewards (YCS) teaching artist and I work for CPS as a teaching assistant. I didn’t have a profession in art, but I always had art in my heart. I’m lucky to have YCS because it makes me find myself in art the way I’ve always wanted to. I’ve always loved working with youth and young children. When I first stepped into YCS it seemed like a great summer gig. The more I spent time, every season, the more I became a part of the family. It revived me. We became a flock.

Irina Zadov (she/they): I am a community-based artist and educator. I loved what you said Juliet, and I think your experience of coming back to art has really been what this has been for me too. I was privileged enough to have art classes growing up, but I never felt like I could devote myself to artmaking full time or from a place of real freedom because I’ve always had to work and make money. As an immigrant and a child of immigrants, I was always told, “You have to get a job. You can do your little art hobby on the side.” It wasn’t until recently that I was able to make more space for myself as an artist. Young Cultural Stewards and Art Seed have created that space for me.

For me, art-making is rooted in relationships, and it has a lot less to do with creating objects or performances and much more to do with deeply listening to young people, elders, and all of the different community members we engage through our programming. Mutual aid work and being in garden spaces and learning from powerful community organizers feel as much a part of the art-making process as creating a performance or making a painting or sculpture.

Najee Zaid-Searcy (any and all pronouns): My individual practice has evolved over the years. I have always been involved with the arts in some way from when I was a little child. Similarly to Irina, I had a lot of exposure and access because my mom moved me and my sister to Dekalb Illinois, which is a little enclave, a rural oasis. It’s this really interesting university town where there were arts resources and cultural resources available. I didn’t realize how informed by that engagement I was until I moved into the city and started doing makeup artistry. Over the years, I always returned to some kind of art.

Aside from what we’re told as individuals is success, we also have this amazing opportunity to define our lives outside of celebrity, exceptionalism, money, these other pillars that have been defined typically by capitalist systems. We get to choose how to survive and protect each other and love on each other. So as I started to unpack my queerness and started to unpack my Blackness and started to unpack all these various identities I was holding, while being 19 in a large city and going out when I shouldn’t have been going out, I started to see and be inspired by all these people who had bravado and this amazing amount of confidence. My practice evolved from something that was capitalist-based, and maybe even patriarchal success-based, into supporting others through my work and to embracing change.

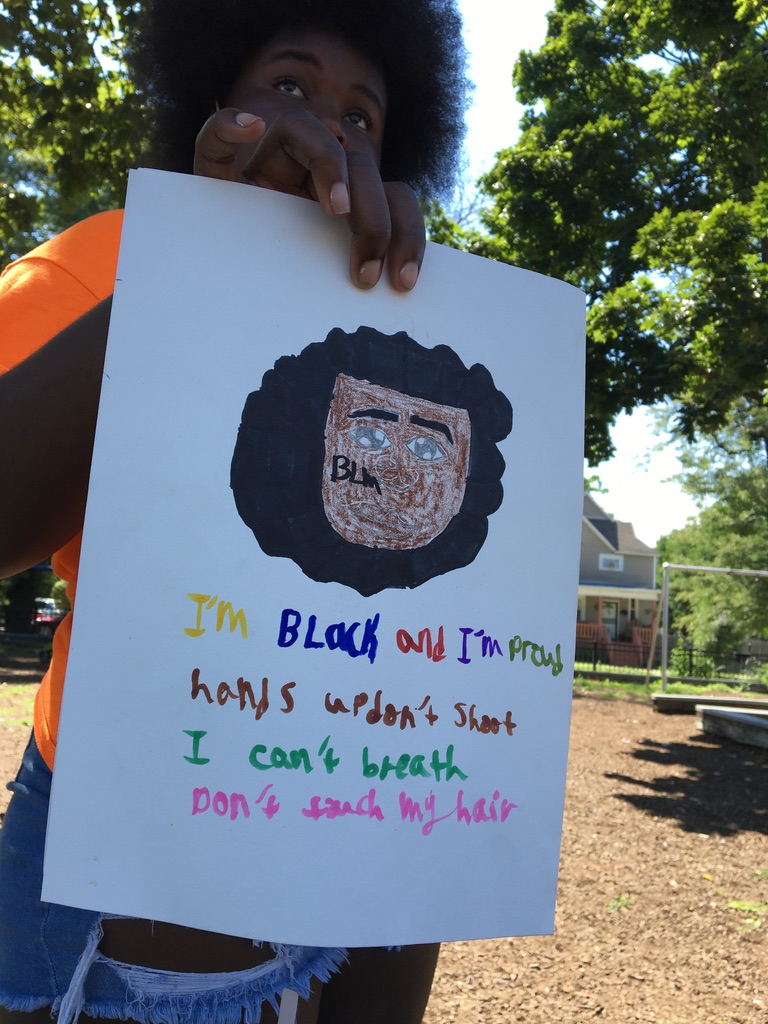

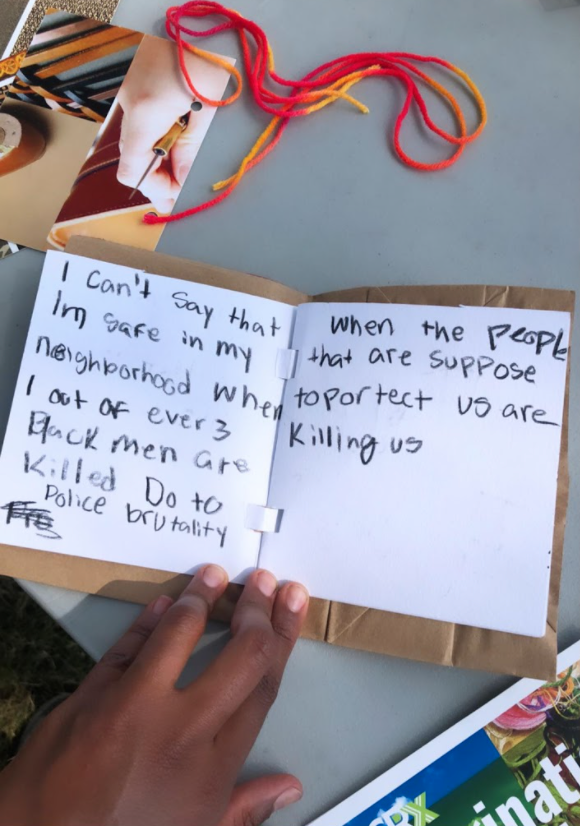

A couple years into being in Chicago, we experienced the wave of the slaying of Michael Brown, and I started to dive into activism. I always felt really insecure about my activism—you know, “Am I enough, am I doing enough, do I know enough? Am I bringing enough to the table for Chicago, for Black people, for queer people?” I started to get in touch with artists who were thinking in similar ways, and that’s when I started doing youth work.

When I had gotten into arts education, initially I did get into that hamster wheel of proving myself, knowing the most, being the MVP in the room, but then I was like, no, I can sit with community, invite a few people into my studio—at the time I was an artist in residence—test out a couple of ideas, have fun, and make a meaningful impact. That led me to working with the parks. Since I’ve been in this role, I’ve really been able to step into the brilliance of others. It’s been so relaxing and soothing to be an administrator. Arts admin to me is not designing everything yourself. It’s co-leadership, it’s about maintaining certain resources available, being in conversation, allowing others to guide you, and using your pen and your creativity to make dreams come true for your community. The more I stepped into that, the less tension I had in the workplace, the less tension I had with myself and the more confident I felt in my role in the city in the world.

GN: Can you speak to the idea of reparations? What is the responsibility of artists and educators to lead the work of restoring, repairing, rebuilding, and transforming harm?

NZS: Every day is so much more than the last in these times. I honestly can’t even grasp the impact of reparations right now. Let’s go back to some of our pedagogy and values of emergent strategy and flocking. If artists and educators are part of a flock, there are times where yes, we are going to lead the way and we are going to help to make, uncover, that which has been hidden, that which lies within the harm, in a way that is socially and emotionally informed, that’s trauma informed but is also a low pressure environment. It’s not about being a therapist and pressuring people into releasing those vulnerabilities, and more about accepting how communities are actually digesting, processing, and exchanging their emotional space, their spiritual, physical space, how they’re navigating. From what I see, I can’t speak for all educators or all artists, we have a unique way of synthesizing information and being an intermediary between folks who are responsible for changing the larger picture, whether that’s activists, politicians, ambassadors, parents, schools, so we work as an intermediary between different bodies/entities to help process and exchange information.

I also think a way we lead is taking valuable gifts of resources and redistributing resources because the leadership comes from within those same communities.

JM: Speaking of leadership, I feel like us as teaching artists have been instilled with leadership, but I realize leadership is not to say I should try to put the light on myself but uplift everyone around me.

IZ: The only thing that I’ll add is to uplift some of our community partners. In addition to working with phenomenal teaching artists who are so brilliant and so talented and have such deep relationships; part of our work has really been to connect with folks that are the grassroots organizers, the builders and the connectors; and have years and generations of trust within their own communities, and that has really informed how we think about reparations.

Everything we do, we do in partnership and the idea for Reparations for the Earth came from multiple years of exploring these concepts of Emergent Strategy and building on the wisdom of adrienne maree brown and working with folks like Tonika Johnson who are uplifting and making visible structural racism and segregation and then reading folks like Robin Wall Kimmerer and thinking about gratitude and reciprocity and what it means to repair and restore and transform harm that has been impacting this continent for 400 years, if not longer. So the way we arrived at Reparations for the Earth came through many years and many seasons of us working in community and thinking about what is our role when we think about environmental justice, ecological art, and cultural stewardship.

GN: I love the way you all talk about the abundance of resources in our communities. It feels like so much of that is present in Braiding Sweetgrass. Who are the teachers and what kind of knowledge are you weaving together and helping to take center stage in the Reparations for the Earth Curriculum?

IZ: A component from Robin Wall Kimmerer and Braiding Sweetgrass that we’ve used a lot in the work is the Honorable Harvest and that’s really about gratitude and reciprocity.

JM: A lot of the curriculum that really stuck with me and that I learned a lot from is putting nature first especially in our youth’s lives and in our programs. Just being able to say “Hey let’s go for a walk,” [or] “Hey, let’s pick up some sticks and create with that as well. While we’re at this park, how can we beautify it? Do you see garbage. Can you pick it up?”

GN: When I was reading through your activities, I noticed the presence of picking up making supplies from the spaces you’re in as well as meditation. In the meditations you describe there’s this element of imagining yourself as a piece of nature.

JM: I must give credit where it’s due, and that was my collaborator Klevah who is amazing at meditation. They were able to include children by making it as simple as “Let’s use your imagination through meditation,” and keep their creativity going. It was such a fun experience to use meditation in such a simple and [a] very, very fun way with kids plus, at the end, we all felt so much better. We all felt like it did make a difference in all of us.

GN: That reminds me of what you were saying earlier, Najee, about how it’s not like therapy, it doesn’t have to be hard. You go from this question of the honorable harvest and recognizing nature as a teacher and recognizing our own gifts, and that experience doesn’t have to be weighty, it can be really nourishing too.

NZS: Being in conversation, time to me, at least, is not linear, so it feels like we are in conversation with all aspects of life in transition and there’s the cumulative work of our elders and our ancestors, and then there’s also the expansion of that concept that it’s not human centric. One thing that we continually learn from our folks at the American Indian Center and Chi Nations Youth Council is the plant and elemental ancestries that exist and being in conversation with them as teachers and learning and that it’s not an instant exchange. Not everything is harvestable for you specifically but you can also celebrate the harvest of others. In us celebrating the harvest of nature and the harvest of others, it helps us to celebrate our own and be a midwife to that process. Feeling excited about when the time is ours to bring those harvests back to the community and whether that’s human, nature, elemental, and also thinking about the future.

GN: I would love to hear from you all about how you’ve built a flock together in your collaboration. That element of flocking, of stepping up, making space, celebrating one anothers’ harvest, how does that manifest for you all?

JM: I did have a youth with a crisis type of home situation. I was so lucky that Irina was holding my hand throughout the whole process of helping this youth out. It became more than a work environment. It became just relying on her and Najee’s support. Their love, their strength helped me realize, “Woah this was intense.” What I did at that park every day for that youth took away from the realness of [what] was going on. I gave them that escape, and that was amazing. My flock was always there. I was experiencing something for the first time. I didn’t know if I was doing enough. Was I doing it right? I was always made to feel like, “Yeah, you are. You are doing exactly what you need to do.”

IZ: I do think the gratitude and reciprocity in how we treat one another really shows. It’s a felt difference from these systems that we’re in that can be very punitive and very militaristic and hierarchical. As I’m sure you know, we have protocols. We have to call the police, we have to call DCFS. There are so many very harmful practices that are baked into youth work, and I think part of our approach is to offer alternatives. What Najee was referencing before about restorative or transformative justice; holding peace circles, practicing vulnerability, creating brave space agreements, thinking about our more-than-human ancestors as guides and as teachers, are all part of offering an alternative.

We always do land acknowledgements and we’ve also started to bring in our more-than-human ancestors and really learning about our Indigenous ancestors on these lands as part of our shared learning. I feel like all of these pieces are interconnected with how we are as a flock and how we think about curriculum and just the ways we constantly shift. Just speaking about being in this moment of teaching virtually, every single workshop we’re reimagining the curriculum because we get instant feedback from the youth and it’s like “Ok we’ve got to shift, we’ve got to flock.” There’s never just one leader. We’re always following each other and learning from each other.

GN: A curriculum is a beautiful tool. It’s also just a snapshot of this much larger connection and ongoing process. This isn’t just a series of activities, but the ongoing relationships, the growth of each of you over those years. Do you have particular stories from the summer, moments where you saw this work in action, moments where there was a surprise or a shift or something that came out of the world and struck you?

JM: I so miss the youth. I’m just speaking on my first summer there. My aha moment was with another youth. This youth had tried to be in the regular camps previous years. Such a character, a strong character. This kid got kicked out of camp a lot. With me, he made it through the whole program. The time and space that myself and my co-artist provided—a little bit of love here and there because this kid went through a lot. I got to know the backstory, which was a story. We gave him the space if he ever needed the space, but also let him grow from mistakes, explained to him a lot, which a lot of adults sometimes don’t have time to do. At the very end of the program was a big hug from him and a “thank you for believing in me.” That was my moment.

NZS: I have a lot of moments. We were having some challenges with the youth because they split off into a very binary gender-based situation—girls vs boys, he/she. I was like, “If there are any queer kids in this room, let me know, hello, because this is a situation.” After doing some circle practices, I realized that there was so much occurring in their lives. Oftentimes, from the program steward capacity, we don’t interface with young people that often in a typical summer. This was my first year where I was like “Oh my god, these kids.” These specific kids were just from different backgrounds. All kids of color. And they just had this very strong dynamic. After we had our circle and after collaborating with the teaching artists, I started doing one-on-ones with the boys. After doing one-on-ones and talking about sexual harassment and what they were going through, they started opening up and being really vulnerable about what their experiences were. I was just like “Y’all are the future.” People talk all kinds of mess about city kids, Chicago kids, kids of color. That [experience] just completely reinforced what I already knew, which was that these kids are really great and they just need somebody to talk to and to encourage them. It doesn’t make them any less. That’s why we’re here, and the relationships were beginning to be restored. They were beginning to communicate with one another across enemy lines and it was really quite fabulous and elegant.

IZ: Starting at the beginning of the pandemic when all of our programming was shut down, to Najee’s earlier point about liberating resources, we were thinking like how can we support all of this amazing mutual aid work that’s happening in the city. We remembered that we have access to Park District vehicles, so we teamed up with our friends a LVEJO and Getting Grown Collective and started delivering groceries. Najee and I were given a list of homes to deliver to and names of people to call, and one of the homes had 14 grocery boxes, so we’re thinking either this is a big family or this person knows the whole block. That was the first day we met Mekazin Alexander. We drove up to 69th St. and low and behold Mekazin and her husband were out on the front porch and I think one of her grandkids was there to help us bring in the boxes, and Mekazin says, “If you have time, come visit my garden.” Of course, we were so excited.

We walk down the block and here is this gorgeous plot of land. There are fruit trees and there’s collard greens growing as high as my waist and there’s a stage and there’s a fountain and there’s a refrigerator on the side that’s being turned into a cooler. Mekazin starts sharing her vision with us about transforming this vacant lot into a community center and she tells us about the work she does with the teens in the neighborhood, the youth employment work, and job training. She tells us about her reproductive justice work as a doula and that she wants to turn the lot next door into a health and wellness center for people who are pregnant who are giving birth. She tells us about the movie nights she has in the neighborhood and the performances they have on the stage. You just see the power of somebody who is of their community really committed to building power. That day and that interaction really transformed all of our programming for the rest of the year. We started coming out to the garden and volunteering. We started bringing our youth to the garden. It became one of our sites for programming. We’re already planning next summer’s programming. Meakzain is starting a non-profit and she asked me to be on the board.

It’s all of these things, you can see the seeds growing. It’s just so powerful because you can see how everything that the Park District and these big well-funded institutions try to do is happening already in Englewood in these communities that the media portrays as lacking, are actually so abundant and there’s so much love and resourcefulness and agility and creativity. Just think about true reparations, making land available to residents, making water available to residents, having people grow their own food, and create their own programming. Just imagine what would happen if all of these city agencies gave the money and resources back to Black and Brown and Indigenous people and support BIPOC sovereignty, which is due. That story gives me so much hope about what’s possible. I think we all have stories about a time in that garden and so many ideas and relationships and possibilities that were planted there and are still blossoming.

Featured Image: Teaching Artist Abena Motaboli and youth gardening at Mae’s Garden and Earl’s Kitchen, 2020. Photo by Irina Zadov.

Grace Needlman (they/she) is a cultural worker and maker preoccupied with questions about collective imagination and agency. As Manager of Youth and Family Programs at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Grace puts museum resources in the hands of Chicago youth and fosters connections between artists and intergenerational publics. They publish and present on youth agency, collaboration, and queering museums. Grace served as director of Corner Gallery and has worked as a teaching artist at Chicago Children’s Theatre, After School Matters, Urban Gateways, the Smart Museum, Arts + Public Life, and Redmoon. Grace’s puppet designs have appeared in productions at Chicago Children’s Theatre, Links Hall, the Actor’s Gymnasium, Rough House, and Redmoon. Grace graduated with a BA in fine art from Yale University and an MA in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths University of London.