Para leer este artículo en Español, presione aqui.

Last month, I had the chance to talk to Chicago-based artist Hope Wang on building different art economies through the act of sharing resources and sustainable practices. You can tell these are some of the focuses of her career when entering her studio. To the left, you find tools hung on the wall, two long tables suitable to place textiles on, then a bookshelf, a coffee table, a chair, and a round ottoman chair. That’s the side which she designated as her studio. To the right, there are three looms (two floor looms and one Jacquard loom), and a human-sized wooden warp winder. That is LMRM. Within the same space, you have two practices, one personal and one communal, interlocked together in a well-lit room that was simultaneously playing Cambodian psychedelic rock.

Hope is a visual artist who is known for her weavings, though she also works with photography, printmaking, writing, and painting. When I think of her work, the distinct CTA (Chicago Transit Authority) blue pops up in my mind. I remember a past work of hers, a blue paper rubbing from the tiles on the edge of the train platforms. I found the same pattern and texture in her studio this time, but now in the form of a Jacquard-woven piece which she made on the Jacquard loom she recently acquired. Her textiles picture scenes from the everyday in Chicago: asphalt floors, brick walls, spray paint. The kind of things you see as you make your way around in your everyday life. Here, the grid of the city is constructed by thousands of threads coded within a meshed grid. But the conceptual connections of weaving don’t just stay in her pieces, Hope is also committed to building networks within the arts community in the city.

“The conceptual connections of weaving don’t just stay in [Hope Wang’s] pieces, Hope is also committed to building networks within the arts community in the city.”

In 2020, she founded LMRM “loom room,” a textile open-studio focused on weaving on floor and Jacquard looms. She co-directs it with Murat Ahmed. Together, they are making accessible tools which are otherwise very difficult to invest in for many early and mid-career artists. They envision LMRM as a “weaving project space” suitable for different artist’s needs. In this endeavor, they are rethinking the ways in which they previously experienced open-studio models and the arts economy.

Hope invited us into her studio for this conversation to learn more about what drives her practice, LMRM’s accomplishments, and some thoughts on weaving.

Carolina Vélez Muñiz: I would like to know how Chicago and the Midwest have affected your work conceptually, visually, or personally. Do you feel like there has been an influence by just being here?

Hope Wang: Yeah, I grew up in Ohio and then came to Chicago at 17 [years old], so I’ve been in the Midwest my whole life. Chicago is where I became an adult and I feel like everything [I make] is informed by the city. SAIC (School of the Art Institute of Chicago) has had a really big presence. The way I hold myself as an artist, and speak and exist in arts spaces is very much informed by the education at SAIC. Also, in response to the education at SAIC; to some of the institutional pitfalls that I noticed in school that extend to the ways people create structures in the city.

This has also been a place where I’ve learned to question all things regularly. For example, we were taught to keep a scarcity mindset. Artists can be so desperate for so little resources, that I see a lot of bending over backwards for scraps. It’s not an equitable exchange. At my school, we were so focused on making good art that we didn’t truly talk about the entrepreneurial side of maintaining a practice. I mean, art materials cost money and self-employment means different tax considerations . The current material conditions to being an artist mean so much of the creative sector is built on self-funded models. So we have to talk about money. We have to talk about fair exchanges and treating people with care. I think Chicago has definitely been a place where people like to say one thing: care and nurture, but then some of the practices don’t always reflect that. I’ve only worked as a professional artist in Chicago, but I’m growing in more conviction that I’d like my art practice to look a bit different.

I’m very committed to the city. I mean, starting LMRM also means that I’m going to be here for a while. I really like what is possible in Chicago, but I’d like to see it in proof.

CVM: As I learned about the history of Chicago and having lived here, I’ve realized that things have a tendency to be driven by efficiency. I think it’s a mentality with the goal of finding the fastest way to produce something and earning as much money as possible. Those values were implemented in (and sometimes forced upon) other parts of the world. So, to me, it has a lot of value to start finding other ways to go about money here. Do you have more thoughts regarding that?

HW: I definitely fall into the trap of optimizing. I think I love weaving, print, and art in general because there’s always room for improvement. As an optimizer and a perfectionist, it’s so easy to fall into the temptation of doing this bigger, better, and achieving milestones as fast as possible. It’s really easy to burn out. Recently, in 2023 I self-imposed a sabbatical from my practice to take a step back, retrain my neurological response to opportunities, and rest to find balance [between my personal and work life]. And I’m still figuring that out.

In the art world in the US, people are so concerned with chasing residency after residency, how many pages your CV spans, and achieving certain things under 30. I was like, I don’t think my art will be that good if I do all of that. I do this because it’s important to create things that feel genuine to me.

A lot of people might have experienced a similar thing during 2020, when we received government funds for unemployment. I just made art and wrote sad poetry during the lockdown period. Obviously, I don’t miss a lot about that time, but I miss not thinking about anything besides this is just my life, and I make art as a symptom of living. That [balance] is something that I feel is a life-long battle when we live in a society that really wants you to spin your wheels faster. Everyday you have to actively choose to slow down.

CVM: Are there people within the cultural realm that have inspired you to do the kind of work you do? Maybe visually, or in terms of a business model.

HW: I think a lot of my values as an artist are informed by performance artists, because they don’t always produce objects they can sell. When it comes to a sustainable practice, that’s an extra big concern for them. Sometimes I think I have no marketable skills, *laughs* besides selling my stuff, and I don’t even like that. So, I have been in orbit of other artists, often multimedia: performers, bookmakers; people whose work involves a lot of craft and where labor can be so slippery to make affordable. Definitely a lot of ceramic artists who are really wonderful when it comes to talking about the entrepreneurial side: tracking data, time, administrative work, materials, and what it really means to have a sustainable practice. As my tax consultant says, “it’s all feasible when the numbers are on paper.”

I’ve also learned about what makes it extremely difficult to have a sustainable practice or address equity issues in the arts. [For example, there are] artists who are paying for application fees. [It’s] basically paying for a job interview. No other industry does that. Also, many other industries don’t have unpaid internships. There’s just so many practices where [I feel like] this just doesn’t work for many of us. People who agree with that are the ones I’ve learned a lot and modeled from.

When I graduated from SAIC, the first place I landed [a job] was at Spudnik Press, which is a community printshop. I had a working fellowship, which I thought was a good exchange until I realized there was so much about Spudnik which was exploitative. It taught me a lot as well. Everyone printing there was so amazing: encouraging, open, and not competitive. It made me want to be in a space like that, as long as the leadership and business model work so people aren’t constantly exhausted.

“When we think about how people are connected, we use a lot of textile and weaving language.”

CVM: You are also pushing away from the idea of the artist as someone who works isolated from society, which you do have to do sometimes to make the work. But you talk about “relational making” and I wonder how you describe it for yourself and LMRM?

HW: Textiles have long permeated our language in how we understand things in general. [As they] have been part of human history everywhere in the world. When we think about how people are connected, we use a lot of textile and weaving language. I also think of my own practice and my work as an arts administrator or organizer as weaving.

When I first fell in love with weaving, it was in school in this room full of looms. You could hear the sound of these looms clacking together. You could be in the studio at 3 am and there might be like five other people there, deliriously making. And everyone’s product looked really different. You could just exchange ideas seeing the cloth wind forward as people [wove]. That was the magic of the studio space. If that had been a solo experience, I don’t think I would still want to weave. That’s why, coming out of school, I wanted to conjure that magic again through LMRM.

Relational making to me is also about being attuned to the reality of what it means to make in this contemporary society. Part of the enjoyment of making things is having common interests with other people where we can find ways to expand our practices together. Knowing how hard it can be to access resources the less proximal one already is to them, it felt disingenuous to talk about how difficult it is and then be the only person who benefits once I do get access. Basically, [relational making is] how we can all grow together by being in an interconnected system of exchange and care.

“Part of the enjoyment of making things is having common interests with other people where we can find ways to expand our practices together.”

CVM: I also feel like weaving allowed me to understand that. There’s a side to weaving that is somewhat masochistic, if you think of the amount of work that comes to only building a few inches of cloth. But if you see it differently, you experience how threads connect to each other and how you can make a stable structure by interlacing these very little and unstable parts. I like how you can just translate that to personal or professional relationships.

HW: Yeah, one single strand of yarn is very malleable, it can look a lot of different ways. But once you connect it or weave it into a structure, it’s much more stable. It becomes very strong. Similarly, there’s a lot one can do on their own, but eventually you hit a ceiling when it’s just you. I think about that as this past year was when Murat and I decided to become business partners. When you put more threads together and you weave them in meaningful ways, it’s going to do something that one strand of yarn wasn’t going to do. You have to build relationships that are stable and committed in order to create expanded things.

CVM: You mentioned Murat and I’m wondering how the collaboration between you two works? How did it happen?

HW: Murat and I met in 2019. We were at a joint benefit auction between Spudnik and Latitude. From there, we just started talking about my experiences with Spudnik and his experiences with Latitude and how we both really believe in community maker spaces. Spaces where the programs, materials, and tools are supported by an infrastructure of staff, where you’re not self-funding every single piece of equipment that you want access to. We really believe in these kinds of low-stakes spaces as being important for artist growth. Murat and I met each other before I started LMRM and we have been honing each other’s ideas and values over the years as LMRM grew.

“I think about that as this past year was when Murat and I decided to become business partners. When you put more threads together and you weave them in meaningful ways, it’s going to do something that one strand of yarn wasn’t going to do. You have to build relationships that are stable and committed in order to create expanded things.”

When I told him about the scarcity of the TC2 loom, as well as the growing demand amongst contemporary weavers, he encouraged me to pursue this idea. Through those conversations of figuring out the financials and the economic model of the space we envisioned LMRM becoming, I invited him to join me as co-director. I recognized I couldn’t and didn’t want to run LMRM alone, even if I acquired a digital loom.

I think we’ve seen so many projects that are built on scarcity, competition, exclusivity, and if that’s the only business model that “works,” it doesn’t really seem like it’s working.

Right now, there’s a lot of overlap in the work we oversee for LMRM because we’re still building initial processes. However, I’m more focused on programming and events that bring the weaving community together at LMRM, whereas Murat focuses more on the technical side of studio operations and how to encourage more experimentation at the loom.

CVM: Going into a bit of a technical side, we’ve mentioned here at LMRM you have a couple of different looms and one of them is the TC2 that you just talked about. Can you tell us what is it and go into the specifics of the particular one that you have here?

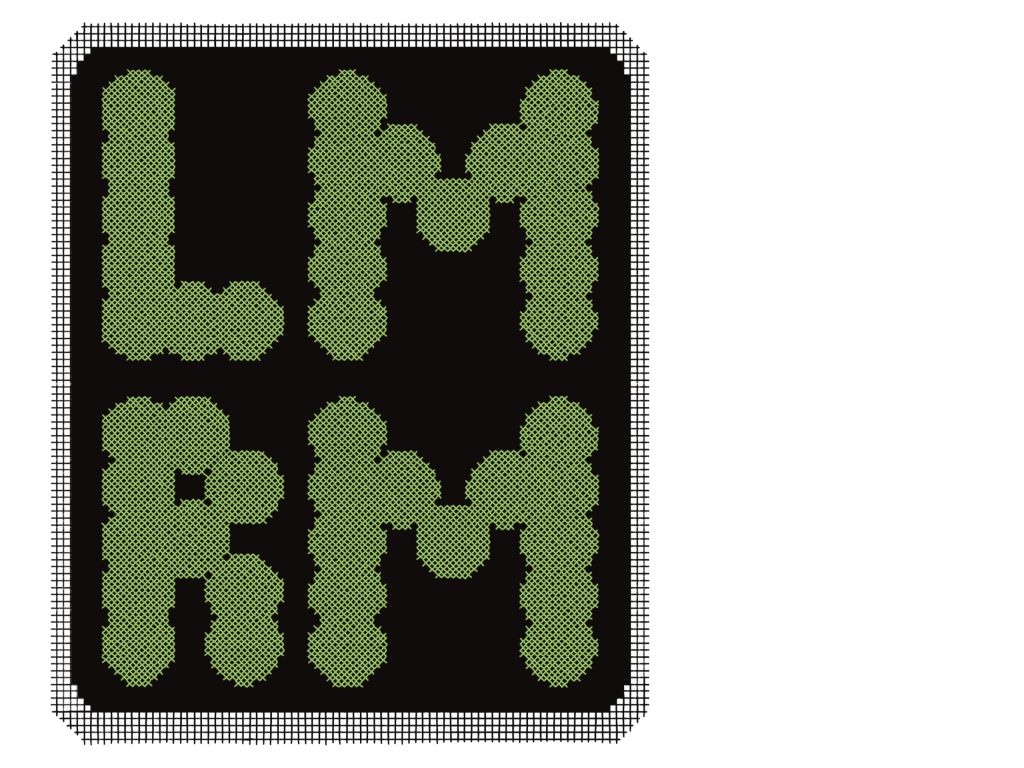

HW: TC stands for Thread Controller. It is a digital loom designed by a company in Norway. From what I understand, the parent company also makes production-mill looms. This particular branch of the company wanted to design a prototyping loom that is a hand-loom, so people could create complicated designs without stopping the power looms. That’s the context of this particular loom.

[The computer is helpful] to prototype, but also to achieve certain things which would be really difficult if you worked on any other hand loom. That became a really exciting moment for artists; being able to design digital images mapping each pixel in a Photoshop file to each thread on the loom. With a lot of other looms, you’re controlling combinations of threads, where with this one you’re controlling every single thread on its own. There’s a higher mode of complexity and customization that is possible on this loom.

Our loom in particular has a weaving width of about 56 to 58 inches. It is the widest one they offer. We have 60 ends per inch, which means 3520 threads in total. We have a double beam, so the cloth can have two separate warps at the same time. So, you’re able to do multi-cloth, multi-color weavings by separating the ends as you’re weaving. We picked this wide loom with multiple warp beams specifically to emphasize working more experimentally in smaller time commitments versus a longer-form residency.

The other side of it is realizing that because it is so wide and has so many ends it requires a lot of work just to put yardage on it. This is not the job for one person. From this, we started to come up with this idea of “Time Warps.” This is Murat’s clever name for our time-banking weaving credit exchange which we want to start out testing this year.

“We’re the second place in the country offering public access [to the TC2]”

CVM: That means that the ideal person coming into LMRM is someone who already has knowledge of the looms and the materials. I wonder if you have leads in Chicago for people who are interested in textiles or weaving but don’t have much experience?

HW: The Chicago Weaving School is an excellent resource for learning weaving and they have wonderful teachers who are super knowledgeable. They’d be a great place to warm up your weaving skills. We also do workshops but they’re one-off and our focus on them is not necessarily education, but more exposure. Eventually we hope to have a network of people who are willing to do private lessons or who can rent time on looms to teach. That’s an option as well, if you want to run a teaching business by renting our looms, by all means do so! Whatever you need equipment for, be it teaching, commissions, hopefully we can be a resource for that.

For us it is really important to stay in a public space where you’re not beholden to the things you have to do in an institution to even learn how to do this. But that’s a slow process, because we’re the second place in the country offering public access [to the TC2]. The learning is very much happening in schools and people are coming out looking for continued access. That’s not the only people we want to be using the tools, so we’re trying to think of ways to have more beginner-friendly workshops, as well as intermediate.

“I think that’s where a lot of people get discouraged or give up on an idea, when they don’t have the resources available to them.”

Part of why we wanted to do an open-studio model is that it can be pretty productive for a broad range of financial (and time) capabilities renters have. For us, if you have $200 this month, then come and weave for a day. And then come back again. [It’s on] how we can make this really incremental, so that it feels like a thing you can continue to do.

CVM: We’ve talked a little bit about what your focus is for the future. To look back a little bit, what have been your favorite moments at LMRM?

HW: Ah! Well, one of my favorites would definitely be [regarding] the first person who rented LMRM’s floor loom. I met my friend Anders Zanichkowsky at Spudnik. We had talked a lot about this idea of a communal weaving studio. Anders is the one who actually pushed me to purchase the first floor loom. Weaving on this loom was the first thing they made after graduating from their Masters program and moving to Chicago. At LMRM, Anders came up with an idea that ended up becoming their business, Burial Blankets. They bought their own loom, and then more looms! And now they’re a full time weaver.

That is honestly the best thing, to be able to support a friend in that early stage. I think that’s where a lot of people get discouraged or give up on an idea, when they don’t have the resources available to them. [They think] the hurdles are just too high, which is fine. But if that is the only thing keeping someone from weaving, I want to see that not necessarily be the case. [Maybe] someone will come here and be like “I’m not going to invest in this, but I will keep on hanging out here because it’s fun.” [I think it’s valuable] just to have the opportunity to try something.

This is the spirit of LMRM for us. If LMRM can be a resource for textile artists and expand access to tools that help facilitate exciting work and relationships for more people, Murat and I both feel this would be by far the most meaningful thing we can do as creatives.

CVM: The incremental aspect of LMRM is making me think of how traditional weavers in Mexico usually learn. Since weaving is such a complicated thing to even conceive of, to learn it on your own seems so impossible. Usually this traditional mode of learning will be taught by little kids being submerged in a weaving community and just starting to play out with threads. Little by little, absorbing more complicated skills, if they’re interested enough. I think it’s really valuable to bring some of that spirit to Chicago and to a culture that’s more driven by capitalism; to bring this play, immersive way of learning, and low stakes.

HW: Also because of capitalism and the global market, a lot of textile making has become outsourced. [The process is] so disconnected from our daily lives. People don’t understand how it’s related to the human body, and some people don’t even know what weaving is. That material knowledge has become so distant for so many people. You see fabric and don’t think a person has any connection to it, and it’s all made by machines. You have to realize that a person with a lot of skilled knowledge still has to be part of it, even if a machine is doing a lot of the work. [In the end,] all tools are extensions of a body. I think it’s important for people to see that someone is still weaving by hand at this computer-assisted loom.

I think that repetitive manual labor is so important as a discipline. Somewhere in the optimization of society, we lost sight of this work as valuable. And by devaluing this labor, we devalued the people doing it. It is slow, it is not glamorous, it is suffering *laughs.*

But sometimes you just have to put in the time and attention to detail for anything to be made. You may not like that you have to tie every single knot, but that’s just what it takes. And because we’re limited by our human bodies we have to put in the time to have breaks, ask for help, and not (always) weave for ten days straight.

“All tools are extensions of a body.”

CVM: To close up, I am thinking if you can give us one thing that you like to do to take a break, either for your body or for your mind. Maybe the reader can try it out.

HW: What do I do to take breaks? I’m really not the right person to ask *laughs.* I definitely struggle with that. I watch a lot of TV. I don’t have a good answer.

CVM: That’s really funny.

HW: I’m so used to making. It’s a really big hurdle for me to take breaks. Maybe it just means doing something that is less consequential, [like] rearranging all your furniture. I like cleaning. If I’m in the studio and I need a break, I’ll just get the vacuum out. For me, it’s just shifting your focus to something else… but, breaks… you’ll have to ask me again in five years.

CVM: Okay, I’ll be back. *laughs*

If you want to know more about Hope or LMRM, you can follow @hopeless_hope and @lmrm_chicago on Instagram. There, you can also find links to her art projects, the studio, and more interviews.

About the Author: Carolina Vélez Muñiz (Mexico City, 1997). Multidisciplinary artist researching the connections between body and space through the making of audiovisual electronic circuits, textile manipulation, and body movement practices. She holds a BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago with a focus on floor-loom weaving and painting.

Her writing practice is dedicated to highlighting projects within visual, sonorous, and performative arts anchored in the idea of “community.” She has published interviews and essays in the Experimental Sound Studio Chicago blog and has written scripts for shows in Radio Cósmica Libre and Radio Nopal in Mexico City. She sometimes writes poetry.

About the Illustrator: I’m Summer. A printmaker, illustrator, and graphic designer from Chicago. My work is inspired by the art nouveau movement, religious/spiritual imagery and concepts, music, and various types of literature. For me, the enjoyment of creation is the patience and trust it requires me to practice.