In Anne Carson’s essay “The Gender of Sound” she writes “every sound we make is a bit of autobiography. It has a totally private interior yet its trajectory is public. A piece of inside projected to the outside.” Carson builds upon these thoughts to create a framework that examines the cultural considerations and consequences of our sounds: what do we listen to, what do we censor? In a sense, Carson’s schema develops an account of value–what sounds do we listen to, what sounds do we remember, what sounds form a life? Viewing artist Jose Santiago Perez’s show PASSIVITIES, currently up at the Humboldt Park based Ignition Project Space, brought Carson’s ideas of aural intimacy to mind by virtue of the work’s inextricable entanglement with memory and the performance of memory. Though Carson is not explicitly engaged with in the exhibition, Santiago Perez’s use of craft and repetition render each piece a memory palace; every work endowed with the ghostly remnants of what was said and never said. Santiago Perez is an artist invested in understanding how we censor and listen and what impact these utterances have within the body.

Derived from Santiago Perez’s past performance work, the pieces exhibited in PASSITIVIES all share a common lineage: they are borne from a bodily, time-based, durational practice. Through weaving and craftwork, each piece is formed by recurrences, echoes, and rhythm. The multiple knots that shape each of Santiago Perez’s objects are memories, ghostly imprints of the artist’s fingertips, corporeality. The artist’s body and memories are positioned at the forefront of the show through the names of his pieces. The titles of Santiago Perez’s works play with language and speech in an attempt to rename and reclaim past censorships. These ideas are partially connected to the artist’s own experiences. Santiago Perez is Salvadoran and grew up in Los Angeles during the Carter and Reagan administrations. This particular historical moment, the specter of colonialism alive and well through American-backed coups in the global south, presented the artist with a childhood that demanded the navigation of the nuances, difficulties, dualities, and discontinuities of living within diaspora under white supremacy.

However, the artist does not confine these conceptions, these acts, of reclamation and naming to moments from his own autobiography. Rather, Santiago Perez utilizes specific memories as points of departure. These breaks, these moments of disruption, occur in order to build a system that both centers and reframes passivity. As Santiago Perez writes in the exhibition materials, passivity is what informs the “choreography of knotting, coiling, and wrapping used in the work, connecting the temporality of touch and the material labor of repetition.” Passivity is thus what is unseen and disregarded but also source of strength, the foundation of the work. In order for this piece to embody that system, to celebrate passivity and intimacy within form, the following section is composed of questions: who, what, where, when, why, and how? Both the artist and the writer have responded to these questions with the intent of weaving together both of our voices. This act of weaving is an attempt to compose our own body, a new type of understanding, a rebuilding of collaboration and dynamic connection. These questions are also not only an attempt to embody the philosophies of Santiago Perez’s work but to reconsider the possibilities of how one can write on, about, and of an exhibition (the artist’s responses are in bold, the writer’s italics):

Who?

nos/otrx

significant others

we others

ante/pasadx

little “i” nearby

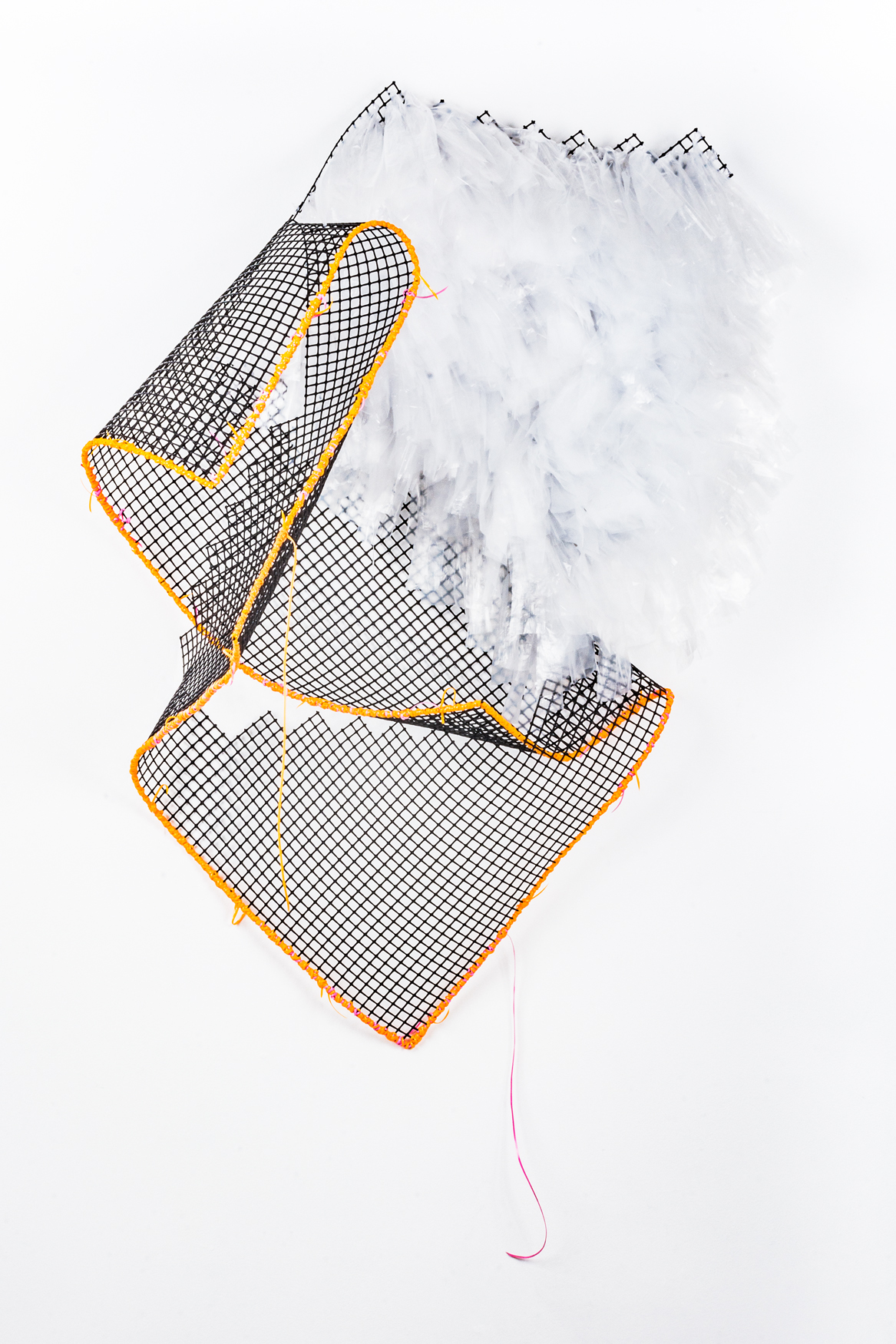

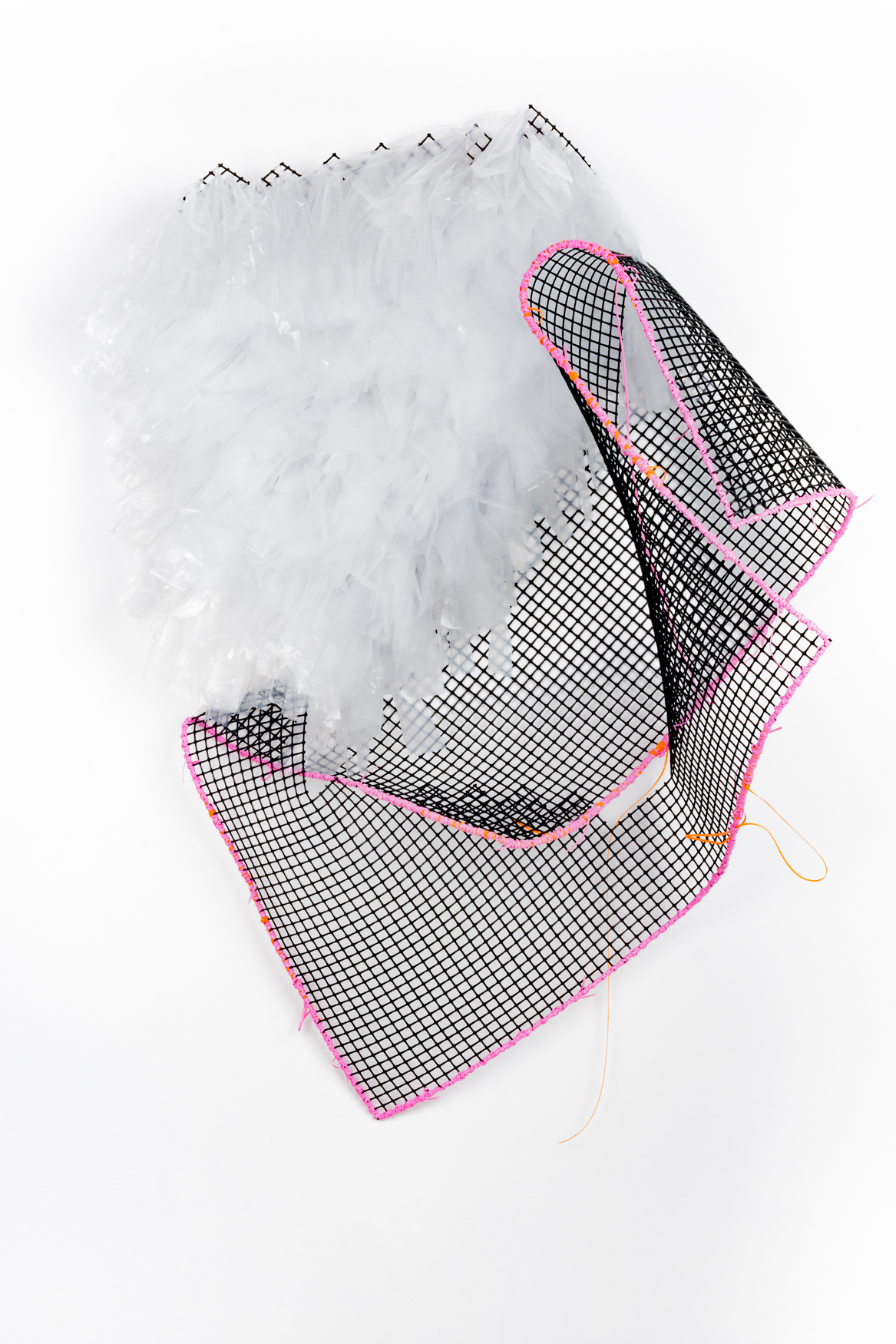

Aytu, Aynotu, and Aysitu speak to one another. They are both accusations and statements, each piece respectively meaning “oh you”, “oh not you”, and “oh yes you.” The objects are built upon fields of black plastic grid work, partially outlined with woven orange and pink plastic cord, with knotted plastic strips softly jutting forward like plumes of feathers. The set, the conversation, represents a dance testing the boundaries of social codes within the vernacular––as told by Santiago Perez it is a verbal game of masculinities. A cruel game based in privilege, one where some men can other and other men are “the Other”. The act of reclaiming can be as simple as holding up a mirror to another’s face.

What?

plastic

plastic baskets – tight; loose

knotted and piled plastic

plastic grids

pink and tangerine plastic

passive cores

compulsory imperatives that shame, isolate, regulate – aaaytuuuú

social scripts that invent pathologies and claim to correct them – S: more like O, Less like E

repetition

mimicry

mockery

refusals to comply, materialized

LessLikeOMoreLikeE undulates and curls outward like a tongue speaking how it wishes rather than what was dictated by codes of whiteness and machismo. Orange and pink cord jut forward, draping, drooping, languidly drooling, delicately posed. Something lovely.

Where?

Before and before

Allí-adentro-aquí

A safe interior

A place that holds

temporarily

An elsewhere

closeby

Sub_strate and Sub_straight are a match, partners. Twins of black plastic gridwork, both shaped into anatomical forms. The interior made exterior. Linear forms jut forward from the body of each work. The movement calls to mind notions of degrees: altitude, temperature, desire. What can we measure?

When?

before and before

when anger and old (inherited) rencores, verguenzas,

humillaciones,

and dolores leave the room (for a while)

when it’s quiet and still

when they’re sensed nearby

when love animates the fingertips

when it’s time

because it’s time

Smile When U Say That is a command, but of what sort? One that leaves the aftertaste of question in an audience’s mind, an unknown interrogative. The generously looping pink cord brings to mind an empty vest, a set of constraints. The ghost of a body in the space marked through the cord, a body brought forth through absence.

Why?

To re/turn

To re/place

To re/value

To re/affirm

To re/name

To un/do

To be/long

Some Measured Splender and Yesterday’s Treasures are both orange plastic woven rope cascading with breaks, moments of blockage. The breaks are symbolized by white tissue, emphasized with pink cord. Memory lays the foundation for both pieces; past sweetness, the basis of splendor. What do you remember?

How?

con las manos

con tiempo

con amor

con paciencia

It takes time

![In[t][f]eriorities, 2019, photo by Karolis Usonis](http://sixtyinchesfromcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Intferiorities_2019_photo-by-Karolis_Usonis.jpg)

Featured Image: Photo of Jose Santiago Perez’s exhibition Passivities, up at Ignition Projects. The artist’s works are installed on both walls and his object series In[t[f]eriorities sits on the space’s main, white table, positioned at an angle. Two pieces, abstract forms of black gridding, are installed on the back wall. Three pieces, formed of woven pink and orange plastic cord, hang on the righthand side. Photo taken by Karolis Usonis.

Annette LePique is an arts writer, educator, and archivist based in Chicago. Her research interests include cinema, race, ilness, and the body. She has written for Cleo Film Journal, Another Gaze Feminist Film Journal, and is a frequent contributor to Chicago Artist Writers. Annette received her MA from the School of the Art Institute in Chicago in Art History, Theory, and Criticism and was a 2017-2018 Research Fellow at the Chicago Psychoanalytic Institute. She is an active performance artist with a background in dance and music. She has presented work in Montreal and Los Angeles.

Annette LePique is an arts writer, educator, and archivist based in Chicago. Her research interests include cinema, race, ilness, and the body. She has written for Cleo Film Journal, Another Gaze Feminist Film Journal, and is a frequent contributor to Chicago Artist Writers. Annette received her MA from the School of the Art Institute in Chicago in Art History, Theory, and Criticism and was a 2017-2018 Research Fellow at the Chicago Psychoanalytic Institute. She is an active performance artist with a background in dance and music. She has presented work in Montreal and Los Angeles.