What follows is an attempt to capture the sensation of Sif Itona Westerberg’s “Twin Flame, Double Ruin”, up at the Driehaus Museum. Soulmates, Twin Flames, are meant to mirror one another, to perform for one another. Each reflects the other’s lack, the other’s failures, the other’s virtues. To have someone look upon you with knowledge and desire, to see yourself in them, is frightening. For what am I, if you’ve made your home within me? Buried under sinew, breathing softly beneath the blood. Yet it is this porousness, the alignment of body and breath, this secret language, that has always been and will forever be deeply, darkly, desperately wanted.

The below fragments should be read as fairy tales. Like Westerberg’s ruins they’re remains and incantations, remnants of a past language between you and I. Decipher this Rosetta Stone. This is a performance just for you.

Smoke curls, curtains part, and stage lights glimmer.

Let’s begin.

Once upon a time there were two lovers cursed.

In Dante’s “Inferno” the second circle of hell is reserved for those who were overtaken by passion in life, ruled by lust. Minos of Crete, the judge of hell, will know you. You are Francesca, you are Guinevere. It began as a kiss, only a kiss, but your surrender was swift, imminent. Paolo, the one you thought was yours, no longer meets your gaze. The ground is not still here. Hot and dry, it’s hard to see, hard to forget. The planes of his face live under the lace of your eyes. Ravenna was cool in the summer. You don’t miss it. You regret nothing.

Once upon a time you held a dagger that cried silver tears.

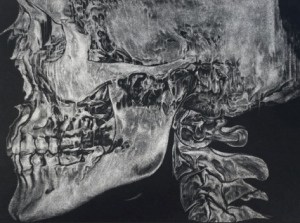

In Ascendance (2023) a polished bronze figure shines like gold. She reclines with one arm resting on her pelvis, fingers curled in the hollow where the thigh meets the body. The other arm raises her torso as Fermacell melts into a single curved line. Her hair licks the air like a compact flame, while one the left leg blooms into ecstatic curls. Rising, becoming, is marked by the loss of boundaries. Fingers and toes meet the sky like Medusa’s snakes, something more and less than human. Westerberg’s figure belongs to the lineage of Archaic kore, with her ambivalent smile and naturalistic features. Ruins are commonplace in Westerberg’s language, both because of her interest in ancient statutory and myth, but also the ruin that can be the outcome of love. The secrets shared just between two, the memories and language that take on a life of their own, ancient rites and mysteries that remain vibrating in place.

Once upon a time a little gold key began to bleed.

In 1945 poet Elizabeth Smart wrote By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept, a memoir in prose that told the story of her eighteen year affair with the poet George Barker. Smart first encountered Barker’s poetry at a bookseller’s on Charing Cross Road in London. This is when she fell in love: through his words she knew him, through his words she saw him, loved him. The couple had four children while Barker remained married to another person. During a rendezvous in the American southwest, the couple was stopped by the FBI at a border between California and Arizona. Due to wartime fears of spying, the FBI cracked down on travelers’ papers. While Barker’s were in order, Smart was arrested at that time and charged with the intent to commit fornication. He left her, but she always stayed; a dynamic that would define the contours of their affair till its very end.

Once upon a time you drowned in a rain of rose petals.

A gasp smells saline, something wet and rotten around its edges. A gasp is a monument, like a wave, for a moment there is nothing between the body and that wet needle shoved through the throat like a rocket. Gasps are borne of shock, surprise, pleasure, disgust; a visceral reaction that cannot be controlled. Gasps happen. A true gasp cannot be rehearsed, cannot be pantomimed. Desire and the gasp share an architecture, a wildness, an empty space where anything could happen next.

Nymphs Gasping (2021) rests on the floor as the faces of the two nymphs arch upward, their mouths open, their throats filled, a sharp intake of air. Can you hear the soft sound of breath? Their hair streams behind them in the undulating lines of Westerberg’s concrete. A wave crests between the two figures, its foam caressing the sliver of space between their faces, it almost touches their open lips. Nymphs, Nereids, were children of the Aegean, the beauty of the water. The titular gasp, that spontaneous wonder, then is borne of beauty, of belonging, of coming face to face with yourself in another form, of seeing the vastness, depth, and unknown reflected back to you.

Westerberg coaxes such delicacy from stone; her lines soft, form changeable. A gasp never happens twice.

Once upon a time a mechanical woman began to dance.

In 1972, Angela Carter’s The Infernal Desire Machines of Dr. Hoffman was released as The War of Dreams in the United States.

Your name is Desiderio. You are the hero of the Great War because you are special: illusion does not touch you. Illusion is the enemy, it causes chaos. You are a son of order. Heritage is a saving grace: for you the walls do not shift, the shadows remain in their place. The air though is always fetid, thick with the dreams that come to you at night. She always comes when the last light is snuffed. Black swan gliding closer, creeping on glass. She is the enemy’s daughter, his prized mirror. Is she real? Fantasy can never be trusted, for who is its author? Is it her? Is it you? Who do you become in the glittering sphere of her eyes? Transformation was always painful, you were not meant to bend. People have lost their minds for less. You seem to disappear each time she leaves. Remember, “I desire therefore I exist”. Yet, it was desire that drove the world mad. Why couldn’t you trust the fantasy? You could have been happy. Did you have to kill her? Medals always weigh heavy on the chest. You regret everything. Even now.

Once upon a time your brother became a nightingale.

The story of the Heliades begins with the story of their father the Sun, Helios. The Heliades were the seven daughters of Helios and an ocean nymph. Each day Helios drove his chariot through the sky. Light follows fathers in this world. Their brother, Phaethon, wanted that light more than anything. To feel the heat, the authority of fathers. To be listened to, to be seen. Sisters see. Myth has it that the Heliades readied their father’s chariot so their brother, just once, could lead the light. He fell a long way, the outlines of the father are not easy to wear. The sisters saw him fall and wept. Their tears flowed on the banks of a river, their limbs curved and hardened into the branches of poplar trees.

Westerberg allows negative space to play against the weight of her aerated concrete in The Heliades Turned into Poplar Trees (2021). Two figures grasp in pain, breasts bared, leaves jut from their temples like constellations of the damned. These poplar crowns expand beyond the confine of the scene, their movement makes you ache like a snap of bone; transformation is never painless, skin breaks and bruises, you remember how delicate the body can be. Each holds the other. Material allows for Westerberg to play with form and referent: the shards of story bring to mind columns and amphitheaters, the frescos of long ago temples.

Once upon a time you looked into a pool of velvet and saw another face return your gaze.

There is an image in The Harlem Book of the Dead of a young woman nestled in clouds of white satin, embroidered with buds and verdant like spring. The year is 1926. A line of posies adorns her brow like a May Day diadem. She is young, too young to be so still, the lace of her gloves unmoving. The girl’s funeral was the inspiration for Toni Morrison’s Jazz, the story of another missing girl, the beautiful and free Dorcas, the object of love and obsession for her middle aged lover and murderer. This is a story of crime and a grand love, both formed by a girl-shaped hole at their very center. For the majority of the book we hear from the affair’s survivors: Dorcas’ friends, the murderer, and his wife. We learn why the murderer pulled his trigger. That reality and fantasy could never align for him, that Dorcas would remain free. She would not be the one in his house, in his kitchen, in his bed. There was a quality of Dorcas that was yet to be written. He wanted to be her author.

This is not how the story goes.

Morrison ensures it is Dorcas who ends her story, that she is and has the final word. Dorcas tells of how she felt the first time she was with her lover, how she was transformed by love’s gaze. It was light and warm, like violet petals caught aloft. In the book’s final lines Dorcas asks her lover, and the reader:

“Look where your hands are. Now.”

Once upon a time the moon began to speak and love hung heavy in your mouth.

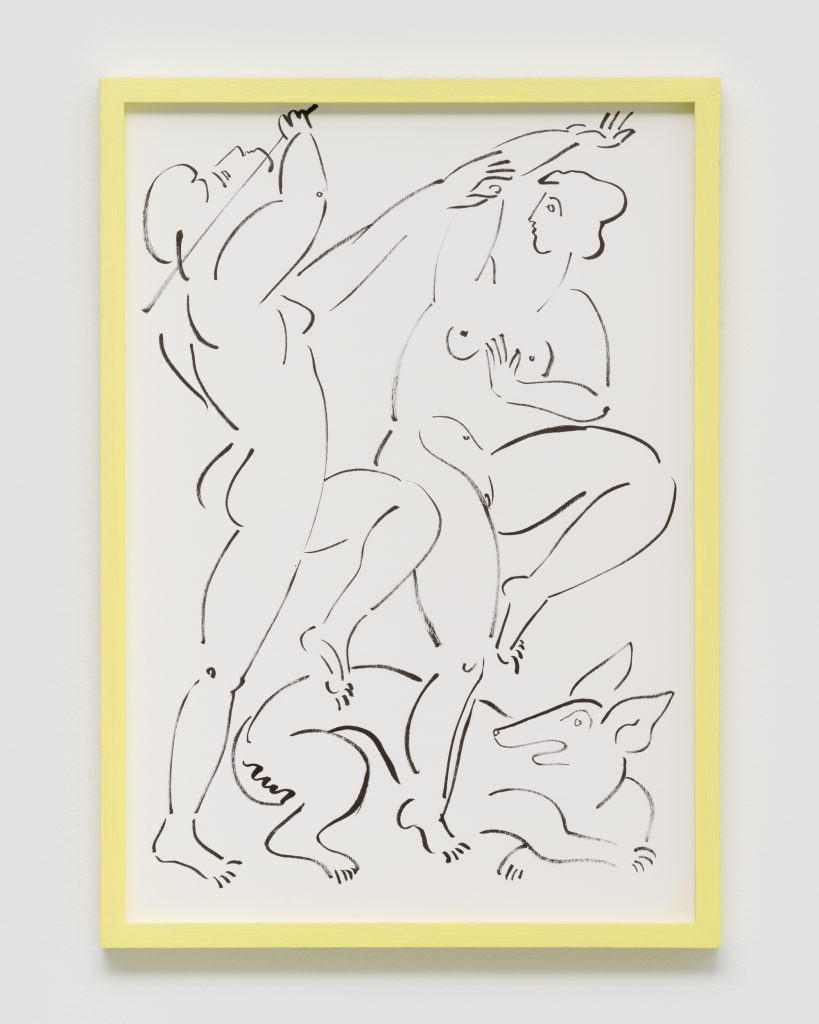

In an untitled series of ink sketches, bodies merge into animals. Ears and horns lengthen, tails whip as teeth are bared. Nude figures dance and leap in lithe lines as creatures, some reminiscent of the centaur or the many-headed Cerberus, weave between these spinning human legs. There is a turn to the uncanny within each of these vignettes, the movement alive in Westerberg’s hand, as we can recognize something in each animal’s face. There’s a humanity, an individuality, to each creature. There’s not much distance, if any, between the human and animal. This closeness, this intimacy, is a quality that the show itself is well aware of: desire connects us, it can turn a saint to a beast. This isn’t a bad thing. If anything, this is a comforting lesson, one kin to that of the Rose from the Little Prince. Yes, we may lose our heads, howl at the moon like never before, and luxuriate in the excesses, but only when that lightning bolt hits. That electricity, straight to heart, the opening that allows us to see clearly for the first time, that’s what connects us.

Once upon a time you became the wolf at the door.

“Let me in”. You scream it every night. You were selfish in life, spoiled and rotten, but he liked your cruelty. The moors of the Brontes’ were a cruel place. You two lay in the heath like it was a bed, blessed and holy. Beholden to the confines of your skin and class, you turned away from his unknown fortunes and future, to a taffy colored cage smelling of silks and closed doors. You tried to explain, once, how you felt; love always seemed inconsequential when faced with the immensity of your feeling. For you and him were one and the same, souls two halves of a whole. Love failed when you looked at him, for you were looking at yourself. Yet, you two were cursed by distance. He heard nothing but love’s insufficiency, its lack. For the rest of your lives you see only pain in one another’s eyes, two wolves perched to devour. You both missed so much. Regret seems insufficient.

Once upon a time love became a blessing, an impossibility, a flash in the pan, a wayward glance, a firework enclosed in your fingertips, molasses on the vine, death behind the eyes, a secret diary, a double life, an honest day’s work, panting breath, the best thing, the worst thing, a message from the future, a scream that broke the day like metal.

Aquatic tendrils bend away from the other in agony, a split begins in the color of their stems. Rendered in concrete, Twin Flame (2024) is intimate in scale, similar in size to the Stations of the Cross in Catholic church or an even older rite, now faded and peeling on a palace wall. The piece could be a plant, a flower, something natural and untamed. There is only this secret, teeming mass. The lines are lithe, the scene quieted by Westerberg’s material. You must look closely to see the hair of a flame, a burning heart wild with heat. Westerberg’s stone heart writhes under the illumination of a single light.

Look closer, what do you see?

Do you recognize it?

Inside this burning heart is a mirror.

Do you feel your absence, your presence, at the center of this story?

I use these stories to write around you, write for you, and keep you locked tight in your crypt. Yet, when I write, you are here, and I am in your bed. Perhaps here is the heart of Westerberg’s show. It’s the dark, soft secret places where you come alive, where the hands that you know better than your own find you once again.

* * *

Sif Itona Westerberg’s “Twin Flame, Double Ruin” is on view at the Driehaus Museum from February 16 to April 14, 2024.

About the Author: Annette LePique’s writing has appeared in ArtReview, Chicago Artist Writers, Chicago Reader, Eaten Magazine, New Art Examiner, NewCity, Ruckus Journal, and many other publications. She received master’s degrees from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the University of Chicago, and is a 2023 recipient of the Rabkin Prize for art journalism.