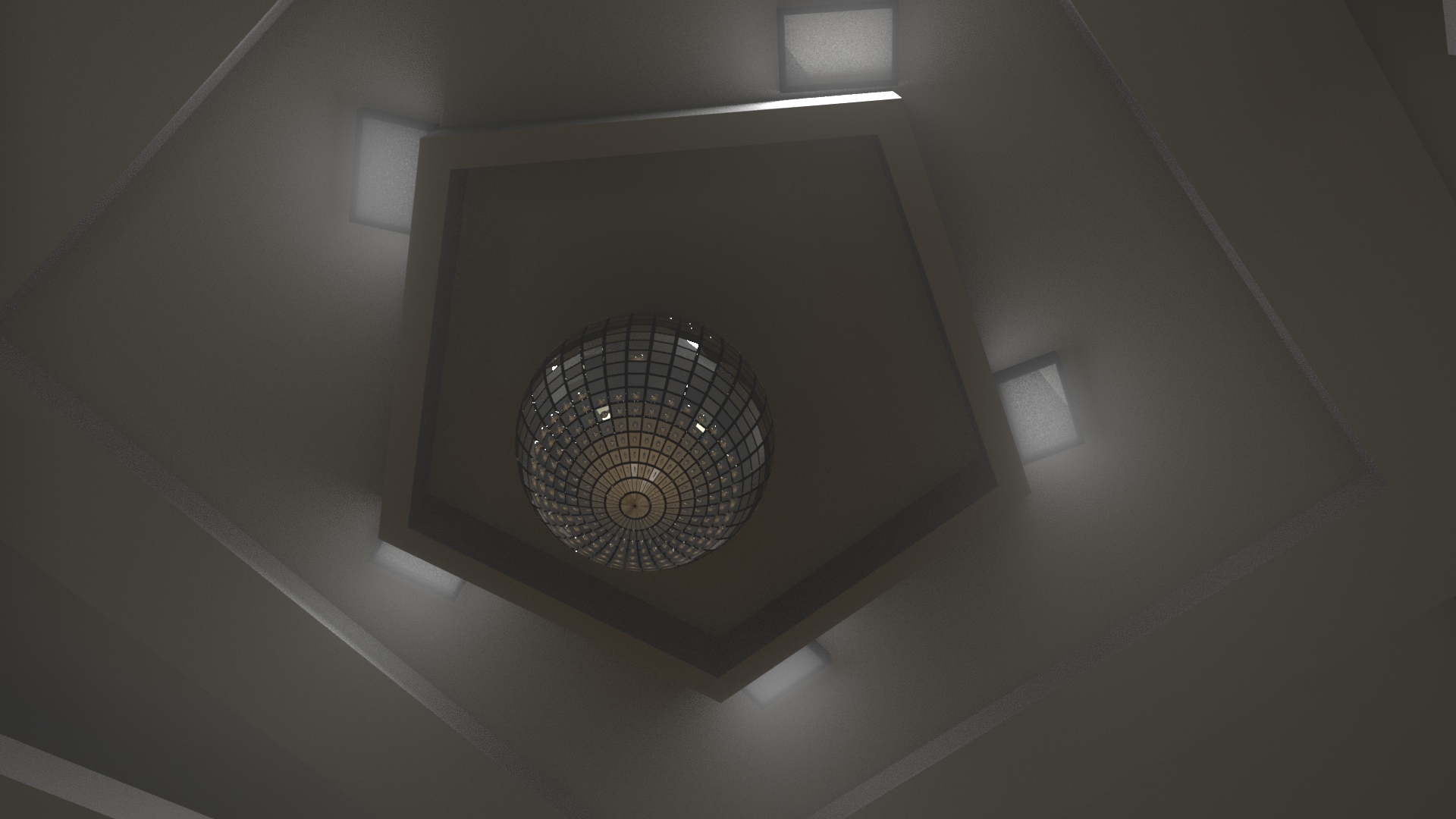

Featured image: Amina Ross, Rendered Image from the film Man’s Country, 2021. A digitally rendered image that has a point of view looking up to a disco ball framed by hexagonal blocky trim on a gray ceiling. Image courtesy of the artist.

Underground: (1) situated beneath the surface, (2) a movement of resistance, (3) an exploration by a group of people to live an alternative lifestyle or form an artistic expression. Man’s Country, curated by John Neff and Rebecca Walls at Iceberg Projects, reflects upon the many facets of what it means to be underground. These spaces can be mysterious, intriguing, hidden, protected, and comforting to be in. They can be a way of gathering in a community that feels like a place of communal strength. At the same time, convening in these spaces can create vulnerability. In the exhibition, artist Amina Ross combines elements of the underground to convey a point that is two-fold: there is the physical underground space that can run the risk of collapsing infrastructure, and also the societal vulnerability of the unprotected, the dismissed, the marginalized. Ross crafts an exhibition in response to this duplexity of underground spaces.

Founded in 2010 by HIV/AIDS researcher Dr. Daniel Berger and a small board—including Man’s Country co-curator John Neff—Iceberg is a collaboratively programed exhibition space providing emerging artists, artists of color, and queer artists with opportunities to develop experimental projects. Originally a historic carriage house, Iceberg Projects was renovated by the architect Robert MacNeill into a small gallery space. Artists such as David Wojnarowicz, Gregg Bordowitz, Steffani Jemison, Abigail DeVille and Oli Rodriguez have exhibited at Iceberg—an exhibition record of promoting historically marginalized communities that Ross speaks to in their consideration of the ‘underground.’ In order to enter the gallery, visitors wander from the street to a gate behind the home of Dr. Berger, follow a trail of sheet rock steps through the garden, then arrive at a small brick building: Iceberg Projects.

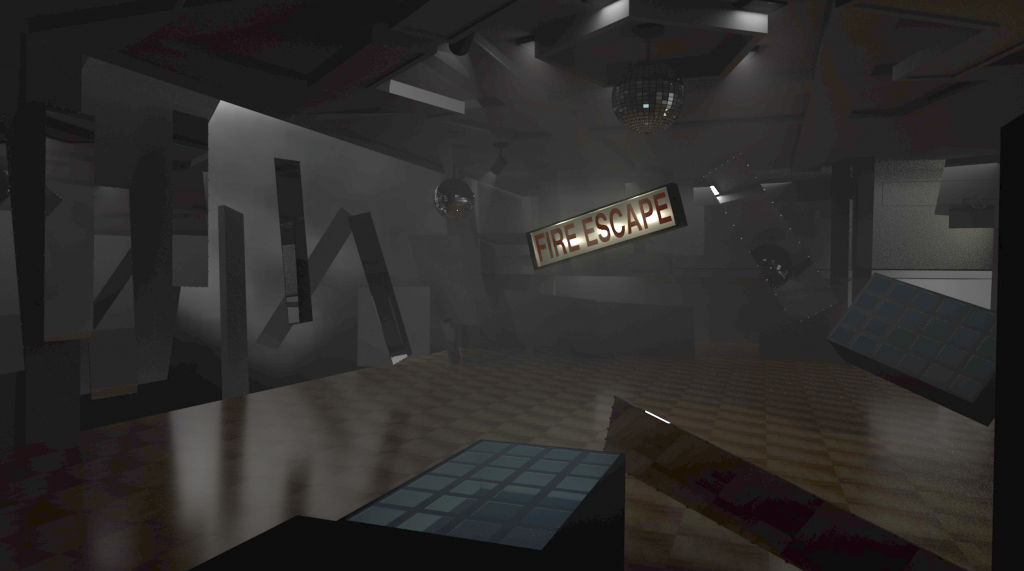

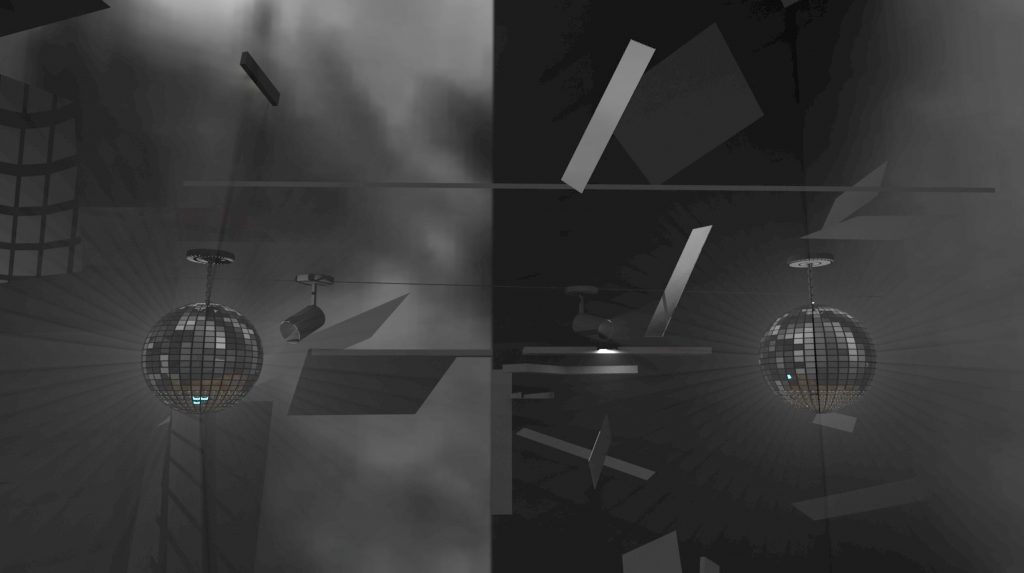

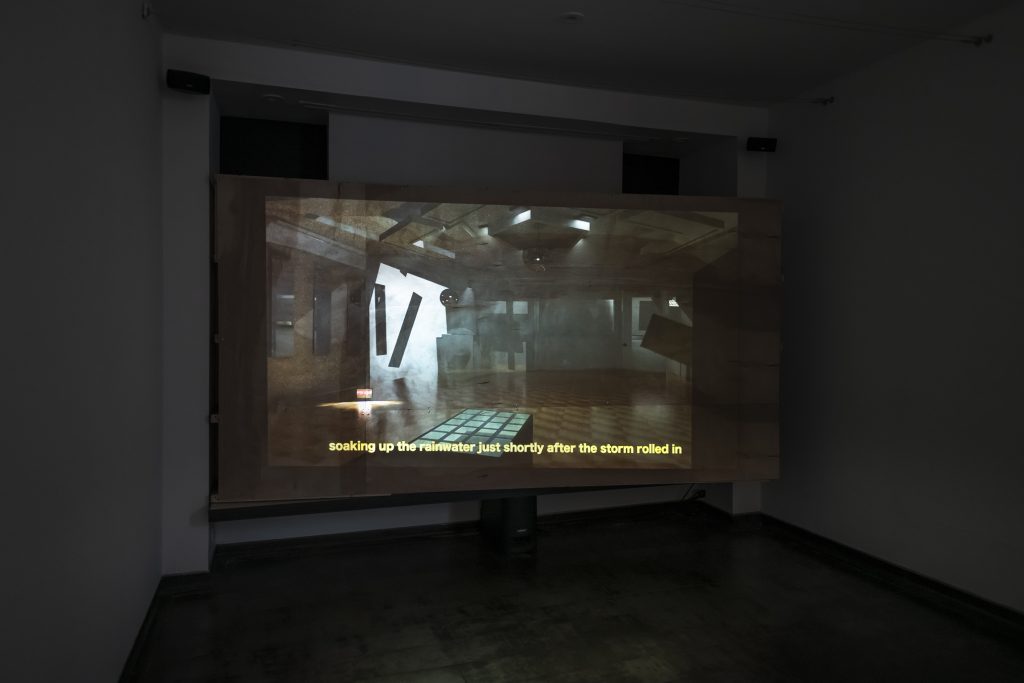

Upon entering Man’s Country, I encounter what appears to be a site under construction; flanked by plywood from opposite directions, the wood brings attention to the architecture of the room and, because of the disposable nature of the materials, evokes a sense of temporality, process, change. The plywood is used for two installations that sit parallel to each other from opposite ends of the gallery space. On the left side, a digitally rendered animation is projected onto the wood grain surface. The animation is titled Man’s Country, taking its name from a former bathhouse in Chicago that opened in 1973. Man’s Country was one of the only spaces for leathermen to congregate in Chicago and built a strong community that lasted decades. Ross’s Man’s Country recreates the bathhouse based on images that they were able to locate online. Never having entered the bathhouse but living just down the block from where it used to be located, Ross explores what used to occupy the bathhouse: the mystery of the space and the desire to exercise fluid embodiment and intimacy. Rather than simply recreate the locker room, disco hall, and tiled floors of Man’s Country as a project of nostalgia or to gain entry into a boy’s club, Ross instead aims to trigger the imagination of the viewer. The animation projected on the plywood guides the viewer through the architecture like a first person video game. The bathhouse is empty, darkly lit with a few spotlights and two disco balls with small cracks. Drums, bells, synth by Ross, and a musical saw—courtesy of Ralph Loza—play intermittently in the background to amplify an enigmatic ambiance. As a viewer, my orientation slowly becomes distorted by gazing into the reflection of the disco balls and mirrors. Eventually, the building’s parts are dismantled and the cluster of architectural bits fade from perspective into a black and white haze, like a memory or a stormy dream.

Man’s Country begins and ends with a blank projection with the exception of small subtitles that emphasize the collection of recorded voices being heard throughout the video. Because of the small nature of the space, sound easily bounces around the gallery; voices sound as if they are coming from someone physically nearby though no physical body is present. The voices—contributions of actors Nairobi Tribble, Rashida Khan Bey Miller, Eli Harris, Yel Rennalls—are reciting poetic verses or phrases that are then broken down into smaller scenes that vary from monologue to dialogue to singing. The first scene, “a wail” as Ross titles it, conveys a process of unearthing, using water as a metaphor for change. “I’ve started to clear out the basement. The room contains a flood…I’ve been trying to house a…a river…To uphold a room around a …a storm. A storm that really just wants to breathe, I guess, you know? To expand itself along the…the air, wide. Something is changing.”1 The voices seem direct as if they are leading me somewhere, similar to the guided visual through the video, but as time continues the voices unravel, leaving me with a chanting hymn: “When the feeling arrives. When the feeling arrives again. When the weather rises. When the weather rises up.”2 These phrases repeat like an echo in dark projection.

On the right side of the exhibition is a large plywood scaffold where a stapled collage of black and white flyers are Risograph printed, wrinkled from water exposure, with repeated and overlapping phrases: “Is a technology. Is not a machine.” “I’m sweating. Is not drained.” “It is gone. It is not over.” The phrases on the flyers, designed with the assistance of Avery Youngblood, derive from Ross’s independent research project “Queer/Bath/House Research Project” that took place during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020—a time that allowed Ross to reflect on community spaces for queer togetherness and intimacy. As Ross explains, their research process is influenced by “intuition, stream of consciousness, and association combined with a cross-disciplinary background research pulling from databases.”3 With research assistant Bao Nguyen, Ross cultivated a collection of images, distilled core questions, reflections, and exercises about bathhouses as a queer space for gathering into a website and forthcoming publications.

The thought exercises on the website present false dichotomies: “The bathhouse is a technology. The bathhouse is not a machine.” “The bathhouse is immersive. The bathhouse is not without a body.” “The bathhouse is sweating. The bathhouse is not drained.” These phrases are then shortened when presented as posters in the exhibition space. Some of these phrases such as “Is safe. Is not secure,” and “To be watched. Not to be seen,” refers back to the notion of the underground as a place of protection and safety for the queer community while at the same time being a place of vulnerability. Like the voices in the video, Ross’s ambition isn’t to convey a linear story with these phrases, or that these underground spaces are either safe or secure, but instead, to use them as a meditation or as points of departure for imagining a space that is yet-to-exist.

Man’s Country recalls a duplexity of past and existing underground space—metaphorically and at times quite literally underground. Simultaneously, it asks us to imagine, in Ross’s words, a new “elsewhere” inspired by these underground spaces for queer togetherness.

* * *

Works Cited:

1Amina Ross. Man’s Country (2021)

2Amina Ross. Man’s Country (2021)

3Interview between Livy Snyder and Amina Ross on November 10, 2021.

Amina Ross: Man’s Country is on view at Iceberg Projects from October 16 – November 28, 2021. It was curated by John Neff and Rebecca Walz. Project contributors included a digitally rendered animation, sound by Amina Ross, musical saw by Ralph Loza, sound engineering and mixing by Alex Inglizian and Experimental Sound Studio, and remote recording provided by the following actors: Nairobi Tribble, Rashida KhanBey Miller, Eli Harris, and Yel Rennalls.

Livy Onalee Snyder is based in Chicago. She recently graduated from the University of Chicago with a Masters in Humanities. She has published in Denver Art Review: Inquiry and Analysis (DARIA), made contributions to Supernova Digital Animation Festival and interviewed artists for Black Cube Nomadic Museum. Currently, she holds a position at punctum books and advocates for Open Access.