“Sleep is by turn ominous, alluring, and reassuring; it mimics death yet offers rejuvenation; it promises flights of fancy and total nothingness. A naturally occurring psychedelic, sleep is the most organic, and economical, narcotic known to humankind.”

Phillip Sherburne, “The History of Sleep Music: Songs in the Key of Zzz”

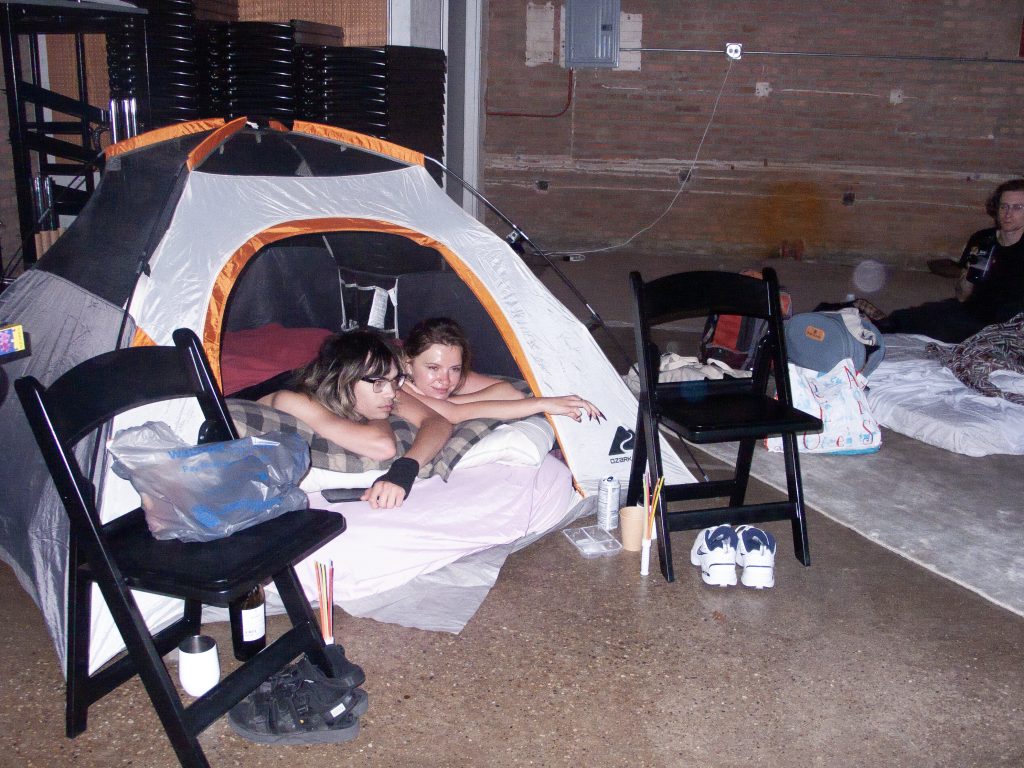

I’m not ashamed to admit that I have a hard time staying awake during concerts. It’s not because the music is bad, rather I feel so relaxed that I’d love to zonk out while listening. As writer Tom Johnson once wrote in defense of his zzz’s, “Despite the pleasant atmosphere, or perhaps because of it, I dozed off after a while.”1 Even when I slept over at my partner’s DIY venue, I never made it past midnight—I still don’t. During shows, I would often climb into bed to the sound of metal guitar riffs, drones, and people trying to have a conversation by yelling over the music at the top of their lungs, and actually slept great in that context. So, when I browsed the trenches of Chicago’s music events online and learned about StretchMetal’s Drone Sleepovers, where sleep is not only welcome but encouraged, I was enthusiastic, to say the least.

Think of Drone Sleepovers as a music campout. Opposite to raves, where people perform for others to stay up past dawn, at Drone Sleepovers, an ambient or drone musician performs for an entire night for people to sleep. StretchMetal, an experimental music event collective, has been hosting these events since 2019.

StretchMetal’s founder and ambient musician, Gray Schiller, shares StretchMetal’s origin story:

“Back in 2017, my friend Eli Smith, an experimental sound artist based in Milwaukee, hosted their own Drone Sleepover. I got to play and ever since [I] had longed to do my own. Years later, via living alone and having open-minded neighbors, I was finally able to take a crack at it. [The first] Drone Sleepover was in my apartment. I and a couple of friends completely transformed the space, clearing everything out of the main hot dog-shaped room and shoving it into the side bedroom. We kept a futon for shared sleep, a rug, and a circle of sleeping bags. We hand-crinkled over 100 sheets of colored paper and plastered it onto the walls. Each window was blacked out with a roll of craft paper. We used my home studio monitors as a makeshift PA and served food on a charcuterie board made of my kitchen table, appearing more like a sculpture than sustenance. The experience was cozy, charming, scrappy, and unlike any Sleepover that came after it.”2

Attending one of StretchMetal’s Drone Sleepovers feels childlike as if going to a sleepover for the first time. Participants are instructed to bring anything they would take on a camping trip such as water bottles, camping pad/yoga mat, pillows, sleeping bags, and blankets.3 People arrive and chat quietly, but around 2 a.m. or so, once everyone settles in and begins to sleep, the performance continues on. It’s thrilling to be in a setting with others who look forward to listening to music while they sleep or those who love the music so much that they’ll endure a sleepless night to hear it. The music guides the mind to a state of relaxation, hypnosis, vacancy, reverie, sleep and maybe even a dream will occur until the rooster set, one of the last sets of the night, which gradually surrenders participants to wakefulness.

Leah, one of the musicians, describes their experience performing the rooster set which started at 5:45 am:

“I started off by playing a few unreleased drone and ambient tracks of mine. A lot of the drone and ambient tracks I’ve been making these days include a lot of sound samples that I’ve taken from my day-to-day, so these tracks were a bit more nuanced and texturized. I then began to blend in the sounds of the washint, a traditional Ethiopian flute-like instrument, with some lofi-house tracks. The vibrato of the washint paired with the soft thumps of the house kicks got everyone up. It was precious to watch people wiggle and stretch and rub their eyes awake. People examined the room, slowly remembering where they were. Some broke their silence and spoke to their peers, others chose to continue their silence and move their body to the music. I felt like I was entrusted to both guide and witness this very human, yet private, moment.”4

As a form, Drone Sleepovers, follow a long history of performances that lasted from dusk to dawn. Some of these include the “Dream Music” of Malaysia’s indigenous Temiar people, chants of Hindu temple ceremonies, and Indonesian gamelan to name a few.5 In the U.S., the early 60’s were a turning point for expanded listening. While the demand to experience music for longer periods of time has almost always existed, electronic innovations helped to make extended listening more widely possible. Early efforts to lengthen performance duration were driven by experimental artists such as John Cage, Le Monte Young, and Marian Zazeela, and the compositions of their performances centered on repetition. Cage, for instance, revived “Vexations” by Erik Satie in 1963.6 The composition—which takes up only a half-page, lasts 80 seconds, and repeats 840 times—was performed by Cage and 11 other pianists. It lasted about 18 hours. The same year, the artists La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela regularly hosted all-night concerts and formed a group with Terry Riley, Tony Conrad, and other musical contributors called the Theatre of Eternal Music. They would produce “dream music” by playing drones and exploring harmonic intervals7 and were early adopters of new audio technology using equipment such as reel-to-reels, drones, and synths, to help stretch out sounds.

Around this time, early electronic music was also packaged to the public as sleep-aids. Raymond Scott’s Soothing Sound for Baby in 1962 was the first three-volume set produced in partnership with the Gesell Institute of Human Development in Connecticut in order to help babies and toddlers sleep. Of course, the record had to be flipped so it wouldn’t last all night, but Soothing Sound for Baby could be seen as the first attempt at a music sleep-aid using electronic music. Today, we have moved far away from mothers singing lullabies. We have white noise machines, apps, and Spotify playlists that continue throughout the night with repetitive sounds to help us sleep, but many of these devices are used to listen individually, or in the privacy of the home. I would argue that we should pay more attention to why there exists a demand to listen to ambient sounds in a setting where we sleep communally. As Philip Sherburne, a writer for Pitchfork, asks of “sleep” playlists on Spotify, “What does the resurgence in sleep music say about the way we listen, and the way we live?8

Within the context of recent experimental music history and of experiential events, Drone Sleepover stands out not only because of its quality setlists but even more so because of how the performances guide the participants in an act of simultaneous listening so deep that they’ll sleep and dream together.

Sleeping is a vulnerable, and usually private act—as Leah noted—and to sleep in a big group stands out. I’m reminded of Jules Romains’s description of a “cinematic crowd” in 1911, where participants enter into a similar state: “The group dream now begins. They sleep; their eyes no longer see. They are no longer conscious of their bodies. Instead there are only passing images, gliding and rustling of dreams. They no longer realize they are in a large square chamber, immobile, in parallel rows as in a ploughed [sic] field.”

I laugh when I start to think about how I might describe the appearance of participants during Drone Sleepover, which is certainly not like a plowed field, but rather sprawled out and snoring. What draws me to Romains’s quote is its ability to open up the perspective beyond the content of the movie and asks us to start conceptualizing how the space of the movie theater, and similar spaces where one experiences absorptive art—such as a music venue—shapes the audience’s perceptions.

The scholar Alan Trachtenberg similarly writes about the audience in his description of Weegee’s People, a series of photographs depicting sleepy moviegoers: “The light that discloses is the same light that obscures within a sense of darkness closing in” and darkness is “the medium in which vision occurs.”9 Roland Barthes has also made note of his experience as a spectator in total darkness and obscurity of the movie theater, he writes that the darkness “touches me in a much more intimate way than the clarity of visual space.”10 These quotes capture the importance of darkness in a space because it offers relief of not being watched, allowing other senses, like listening, to become more pronounced.

While Drone Sleepover is a significantly different experience than watching a film, there is a comparable respite in the darkness during an ambient set where our eyes are asked to be closed. As Leah describes from her perspective, “As a sound artist that experiences burnout, I frequently think about the ways in which we can communally tap into something as intimate and necessary as rest. I think StretchMetal did a great job at providing both attendees and performers with that very opportunity.”11

StretchMetal’s upcoming event in Chicago, Dance4Drone, is their yearly fundraiser for StretchMetal’s programming. It will take place on September 15th at Cafe Mustache.

Works Cited

- Sherburne, “The History of Sleep Music: Songs in the Key of Zzz,” Pitchfork. ↩︎

- Interview between author and Gray Schiller. ↩︎

- “About the Drone,” StretchMetal, https://www.stretchmetal.org/aboutthedrone ↩︎

- Interview with the author and Leah Damte. ↩︎

- Sherburne, “The History of Sleep Music: Songs in the Key of Zzz,” Pitchfork. ↩︎

- You can listen to Vexations here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sKKxt4KacRo ↩︎

- Sherburne, “The History of Sleep Music: Songs in the Key of Zzz,” Pitchfork. ↩︎

- All of the recordings from these performances remain in Young’s closed archives with the exception of one bootleg recording of a 1965 performance. It can be listened to here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7_VHBt4Q0d4 ↩︎

- Jean Ma, “Sleeping in the Cinema” October 176, Spring 2021. 30-52. https://doi.org/10.1162/oct_a_00425. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

About the author: Livy Onalee Snyder is currently based in Chicago. She graduated from the University of Chicago with a Masters in Humanities. She has published in Denver Art Review, Inquiry, and Analysis (DARIA), Newcity, Ruckus, TiltWest, and interviewed artists for Black Cube Nomadic Museum’s blog. Currently, she holds a position at punctum books and advocates for Open Access. Read Livy’s writing for Sixty here.