The ‘Body As Image’ exhibition featuring the work of Kioto Aoki, Colleen Keihm, and Darryl DeAngelo Terrell creates a space in which black identity and body politics are simultaneously explored within a historical context through the literal lens of photography, while also repositioning itself outside of these narratives by using alternative modes of image-making such as cyanotypes and photograms. This exhibition, presented by Chicago Artist Coalition, features HATCH Project artists-in-residence and was curated by Chicago-based Sabrina Greig, who is the current curator-in-residence. The exhibition is on view from April 27th – May 17th.

Walking into the Body as Image exhibition at Chicago Artist Coalition’s gallery, I immediately noticed that each piece, as well as the gallery itself, is completely absent of color. However, that is not to say it is lacking variance in tone. The stark white of the walls of the gallery provide a dramatic contrast that allowed me to take notice of the subtle variations in tone in the many shades of blacks and browns present within the work. Not only do the darker tones in the exhibition become more pronounced through this coherence, but also the shades of white become brighter, harsher. Even the light coming in through the window during the time that I arrived during midday began to wash out details of the space in which it passed, glaring in a severe diagonal across one of the walls. The light from this window slanted across a wall where three photographs hung in a reversed diagonal line: “The Stance” by Kioto Aoki, “Weight and Measure” by Colleen Keihm, and “After Uematsu Keiji” by Kioto Aoki.

When I asked curator Sabrina Greig about the non-traditional placement of these three pieces, she explained:

“Since this was an all photographic show, I wanted to be conscious of the ways the 2-D works were installed – I didn’t want the exhibition to appear too flat or sparse, given the nature of the medium. So because of this, I made an effort to install the pieces in a way that highlighted their dimensionality. On the first wall that features “The Stance,” “Weight and Measure,” “After Uematsu Keiji,” I wanted to vary the height of the works in space – especially since Keihm’s work deals with challenging the horizon line in traditional art historical thought. This is why I chose to place Aoki’s pieces both above and beneath Keihm’s photograph on the front wall, in an effort to encourage viewers to think about how they receive information based on the orientation of the work in space.”

Coincidence or not, the gelatin silver print “The Stance” became consumed by the triangular patch of light coming from the nearby window, which perfectly reflected and inverted the image itself; a pair of feet consumed by shadow, with a small, square patch of light illuminating the toes.

These details immediately brought to mind Glenn Ligon’s “Untitled: Four Etchings,” (1992) which shows the words: “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background,” in black, which is in fact set against a sharp, white background. This relationship of subject and white space is surely not a coincidence, as many of the works posses a similar dichotomy, exploring this relationship of black and white space within the frame of each individual piece and also in the interaction between the works within the walls of the space itself.

This spatial investigation can be seen clearly in Kioto Aoki’s piece “Findings,” created on 16mm black and white film. The piece’s medium creates a stunning effect, producing a hazy, atmospheric view of an interior seen from a first-person perspective. While watching, the viewer is led through an interior until we reach a patch of light coming in through a window. The brightness of the white is somewhat jarring, the light appearing almost unearthly. Aoki states that this is an “environment of exploration of space via bodies of light.” These bodies of light become living, dancing bodies in her other film being shown across the room, “Duet in C(amera).” Here, two women dance with and around each other, but their bodies become abstracted by the cropped frame, cutting them off at the waist so that the viewer can only see legs wearing black leggings moving amongst a white background.

When the camera eventually pans up and the viewer is able to see the full image of the dancers, we are not just presented with the two bodies, but the body of the person filming, all through a mirror. I am suddenly jolted into the frame, into the piece, becoming both viewer and participant with my hand stretched out before me towards the dancers. Aoki cleverly muddles our role as spectator and bystander by placing us within the film among its subjects. This piece was projected onto a wall next to Colleen Keihm’s photograph “Partial View,” which shows an eerie, black and white interior space that is unfilled and unspecific. Like several of Keihm’s other photograms in the exhibition, her images deliver harsh contrasts in black and white that do not appear unlike the space I stood in; if void of artwork, merely a white cube.

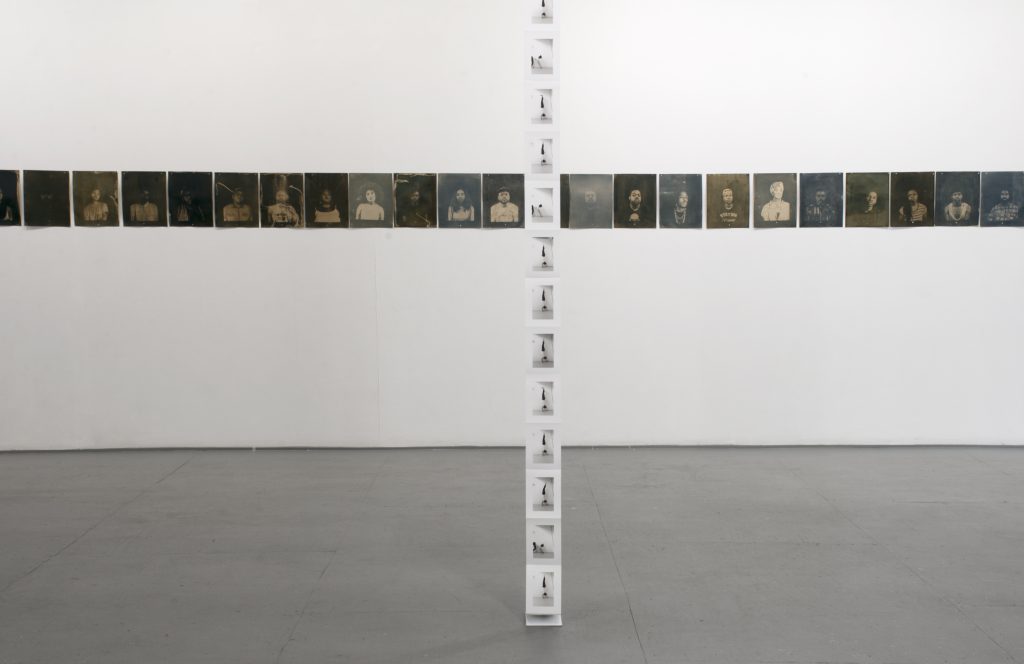

In the center of the gallery space, Kioto Aoki’s piece “After Uematsu Keiji-Column” cascades down from the ceiling, which is displayed such that it seemingly intersects another piece, “#Project20s” by Darryl DeAngelo Terrell. Both pieces contain a series of photographs with the figure as its focus. However, Aoki’s piece, hanging vertically, is dominated by shades of white, while Terrell’s piece, hanging horizontally across a wall, is in shades of blacks and browns. The presentation of these two pieces in an encounter of tones and imagery forces a consideration of the politics of space within the politics of race. Not only because of the creative display methods being used here specifically, but also from the content of Terrell’s work. “#Project20s” is a series of portraits that explores the “displacement of Black and Brown communities by way of gentrification” through the black and Latinx people it affects. Each subject is directly facing the viewer, not combative, but instead strongly stating, affirming, representing their story and their resistance.

Terrell explains, “’Project 20’s’ deals with the resistance and survival of Black and Latinx people between the ages of 20 and 30. It is inspired by my upbringing in Detroit and my love for contemporary Hip-Hop music. ‘Project 20’s’ comes from two specific songs, “We Don’t Care” by Kanye West from his College Dropout album, and “Chapter Six” by Kendrick Lamar from his Section 80 album. Both of these songs speak about the life of minority youth in marginalized communities; struggling to make a living and be happy by any means necessary. This, as a result, leads a large amount of Black and Latinx youth to either end up in jail or worst dead. I found this topic to be more important to me as I found myself making Chicago home and seeing how gentrification and poverty were affecting black and Latinx Youth (i.e putting them in positions that marginalized them even more).”

Terrell’s method brings to mind several art historical references. The portraits are created by cyanotype – a photographic process that creates one unique print, which is then stained with black tea or coffee. This series references back to Louis Agassiz’s “The Slave Daguerreotypes,” whose images were also appropriated for Carrie Mae Weems’ series “From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried,” 1995–1996. My mind immediately connected the process of staining these images in tones made from alternative methods with the work of Kerry James Marshall and his process of mixing his own black skin tone that speaks outside of the white-dominated art historical narrative.

The portraits in “#Project20s” confront notions of identity within race and gender by positioning the viewer in a place where their gaze is being met and confronted. By using an alternative photographic method, the presence of the photographer suddenly emerges in a way that it does not in digital photography. Digital photography sometimes produces infinitely manipulated images that are no longer seen as depicting truth. In a time where people may see a person in an image on their phone or online more often than they see them in real life, our image becomes our body and the space which this image inhabits informs its meaning. By using methods that emphasize more the hand of the photographer, such as Terrell’s cyanotypes, Kioto Aoki’s celluloid film, and Colleen Keihm’s photograms, these images are taken out of mainstream narratives – out of social media and virtual identities – and into a space that can be reclaimed.

The modes of image-making used by these artists create a new narrative, telling the story by means of an alternative material process. Authorship, participation, and identity are called into question. Particularly in relation to Terell’s work, a quote by Roland Barthes came to mind, “In front of the lens, I am at the same time: the one I think I am, the one I want others to think I am, the one the photographer thinks I am, and the one he makes use of to exhibit his art,” (Barthes, Camera Lucida).

It is not just the viewer and the subject present in the gallery; the one who made the photograph is there, as well. What is changed when viewing a person’s photograph on Instagram versus in a gallery as an art piece? Whose voice is coming through the work? What can be gained by changing spatial context? Each of the works in Body as Image challenges these concepts, exploring the image and the body in space, and the subsequent effects on identity and perception.

Featured Image: Installation view of “Body As Image” exhibition at Chicago Artists Coalition. Artwork on view in the photo are “#Project20s” by Darryl DeAngelo Terrell, “Partial View” by Colleen Keihm, “Duet in C(amera)” by Kioto Aoki, and “Vortoscopes” by Colleen Keihm. Photo taken by Colleen Keihm, courtesy of Sabrina Greig.

Christina Nafziger is a freelance arts writer with a background working in curation, arts administration, and community outreach. Earning her M.A. in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths University of London, her area of research focuses on performativity within the image, virtual identity, and cyborg theory.

Christina Nafziger is a freelance arts writer with a background working in curation, arts administration, and community outreach. Earning her M.A. in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths University of London, her area of research focuses on performativity within the image, virtual identity, and cyborg theory.