The Chicago Archives + Artists Project (CA+AP) is an initiative that highlights Chicago archives and special collections that give space to voices on the margins of history. Led by Chicago-based writers and artists, the project explores archives across the city via online features, a series of public programs and new commissioned artwork by Chicago artists. For 2018, the Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation has funded a series of pilot projects pairing three artists with three archives around the city: Media Burn + Ivan Lozano, the Leather Archives & Museum + Aay Preston-Myint, and the Newberry Library’s Chicago Protest Collection + H. Melt. This series of articles will profile these featured archives and artists over the course of their collaboration, exploring the vital role of the archive in preserving and interpreting the stories of our city as well as the ways in which they can be a resource for creatives in the community. The CA+AP Festival will take place at Read/Write Library on July 13-14.

For this installment, we sat down with Mel Leverich, the archivist from the Leather Archives and Museum as well as researchers Claire Morton and Zoe Kauder Nalebuff. The LA&M makes kink, BDSM, leather and fetish accessible “through research preservation, education, and community engagement.” The following interview has been edited.

S. Nicole Lane: How did you begin archiving? How did you get involved with the Leather Archives and Museum?

Mel Leverich: My undergrad is in humanities and I was specifically interested in digital cultural history. I went to school for archives. In every other country they are separate degrees, but in the U.S., a lot of archivists go to library schools and specialize. You either go into library studies or you go to archives. You can do both, but it’s like doing two degrees at once.

I did a bunch of random things before I ended up here. This is the kind of job I envisioned when I was a student, with the understanding that I would probably never work in an institution like this. It’s like going into law—a lot of people want to do good in the world, but in real life you end up just doing office management in a very corporatized environment. You basically have to just enjoy the work as what it is. I had kind of given up on this fantasy of working in an important “nonprofit”. I saw this job at a time when I was doing various part-time work—so I had to go for it. It’s a really lucky find. It came at a good time in my life.

SNL: What kind of challenges come with working with artists?

ML: We haven’t ever had a deliberate arts program. We have a guest artist space which is about a third of the main gallery. That space, for a long time, has been rotated twice a year— so, six month shows. It has been very open, so pretty much any artist who fits within our mission and community who wants to show [their work] can do so. We’ve never had a stipend or honoraria. We’ve never sought out specific people, as far as I know. There might have been cases where the previous director asked someone [directly].

I love helping researchers, but it’s especially challenging as well as interesting. They’re coming at it from a creative arts perspective. It’s a specific aesthetic, mood, or structure that fits into their practice. Our archives are not organized by color—they are not organized on the same axis that an Artist might work with— they are not organized by color. Because of this, it becomes much more of an exploratory and organic process. We have had artists come in before who have had to be very self-led.

Claire and Zoe are doing a project right now which is very self-led. We don’t know what the product [will be]. There are two sides of [this process] — showing the arts and supporting exhibitions, and also supporting artists as researchers. They don’t necessarily show [their work], they just come here for their own practice. I really only work on the research and support side. I haven’t had much role with the gallery and exhibitions. I’m hoping that this is something we will start to prioritize and that we will actually develop an arts program while being really proactive.

Jose [Santiago Perez] curated an exhibit called, “Material Kink” last year. It was fantastic. It was one of the biggest opening crowds that we’ve ever had because it was done by a professional artist.

Zoe Kauder Nalebuff: We were introduced to Mel through a project at the last exhibition that was on view at the Graham Foundation by one of their fellows this year, Brendan Fernandes. The exhibition was really related to dance, ballet and mastery of the body. In many ways, it was inspired by the sculptural forms that come out of bodily restraint and control that exists, and has existed, for a really long time in BDSM culture, but not necessarily in dance. The control and the restraint in ballet is not visible to the outside eye. The artist, Brendan Fernandes, had come here to do some research. We ended up putting together a selection from the archive highlighting images from the equipment catalogues. In these catalogues, it’s really about the structures, these pieces of equipment that are being advertised and how they restrain the body. It’s this interesting place where these images aren’t sexual, they are really just for you to buy what you need. In that way, they were exactly what Brendan was thinking about in creating the structures that were in the exhibition. Claire put this catalogue together, which really gets at the heart of what the show was thinking about. To me, this feels really representative of the questions we are continuing to think about in this archive and that Mel has talked to us about. You know, this material in other archives wouldn’t be accessible. It would potentially be restricted. Just because something is considered sexual in content or nature doesn’t mean it necessarily is, or that it’s just that.

ML: It’s about people. It’s about culture.

ZKN: I work at the archive at the Graham, and so it’s really about people and what people are doing. It’s exciting. It’s a different relationship with power and control and what we see everyday as well as in archives. I think the word that we keep coming back to is “tension” because there is the archive as an institution of power, which is dictating what is considered valuable and not valuable. You have that same parallel with the contents of this archive. In so many ways, what Mel is actually doing is really opening up what an archive can be and how archives are generally treated. I think something that has really stuck with me is that the last time we were here, Mel was telling us the concept of restricted files in archives and how in many archives this material would be considered off-limits. But here, if there are restrictions, it’s a judgement call or a personal decision of what is not fit for the public. How can you make that judgement?

ML: When you’ve already created an institution to preserve a material that the public considers not fit for consumption, how do you make [those judgements] and how is it valid to make distinctions within that? What is okay and what is not okay? What should be restricted and what should not be restricted? At that point, you’re just applying more and more specific applications of value. That’s why I’m against institutional restrictions. This is supposed to be a radically open and accepting place.

Claire Morton: I think a lot of that was really apparent in Brendan’s project. He brought in this whole parallel between ballet and BDSM, or leather practices, in the sense that the relationship between master and student, or ballet master and dancer, is one of supposed consensual challenge. There is this power dynamic there. That is an art form, or a craft, that is highly valued by society in this way that doesn’t question what the relationship is on a surface level. This project was adjacent to the exhibition; it wasn’t necessarily a part of it. It was something that we talked with Brendan about. We came here originally to find books that we thought would be good for the bibliography. Then we realized, for him, after seeing this visual material, there were a lot of parallels between the two practices. For us, it’s really interesting to think about it on so many different dimensions of a power dynamic—there are so many different parallels. They are so qualitatively different, but they are interconnected in all of these different ways, and we become uncomfortable thinking about them once those connections are laid bare. I think it’s really potent.

ZKN: Yeah, I think so much of working with Mel makes apparent the questions and intentions of all archives and all institutions that hold power.

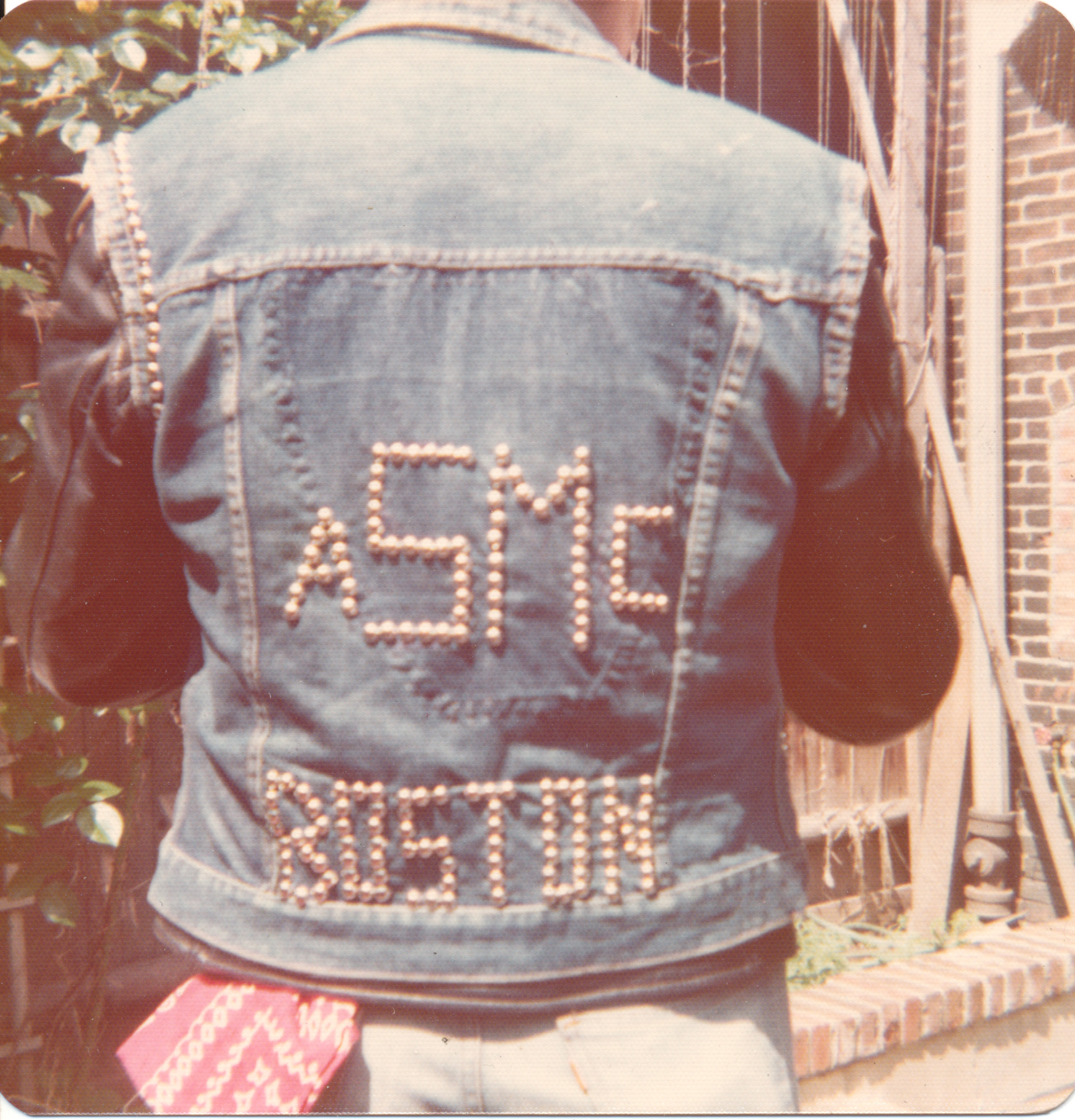

ML: Etienne, the artist [who are auditorium is named after], was also a ballet dancer.

ZKN: I realize we didn’t really give you context about [Brendan Fernandes’ exhibition at the Graham Foundation]. [laughter] It included a series of sculptural devices and contraptions that a number of dancers from the Joffrey Ballet activate at various points throughout the exhibition. The sculptures essentially ask the body to enact these perfect versions of traditional ballet postures. They force the body to hold itself to attempt to achieve these postures towards mastery of the body. When the dancers are present, using [the devices], you see how difficult and complicated structural demands are. When the dancers aren’t there, you know that there is a body in some way that is supposed to interact with [the devices], but you don’t necessarily know how. There is an interesting void and absence of the body. However, you do know that there is supposed to be somebody there in some form.

ML: It makes visible the power and control of the dancer even when the dancer isn’t there.

SNL: Can anyone come and look at the archives? Obviously they have to go through you [Mel], but who comes in here?

ML: Yes, anyone can come. The vast majority of the collection is non-restricted. Ideally, every single restriction has a time limit on it, so it will becomes accessible after a certain amount of time. For the most part, it is community members who want to know—sometimes out of curiosity—information about their region or their community. They want to know stuff we have on their clubs, and often artists and community journalists who want to do research. We have more academically focused cultural historians come in as well. We have a visiting scholar program where we give an honorarium to somebody—we pay for travel costs, and then they have a year to use that funding and come whenever they want. That’s been pretty successful. Those are the major categories—academia, arts and community. Students also come in to do research, which I would categorize as academic.

SNL: Is the archive digitized?

ML: Portions. They started [the archive] in 1991, and there has been an archivist for five and a half years. So only about 40 percent of the collection is what I would describe as processed. Getting it processed so people can access it is a priority. We have had a couple of digitization projects; two of them were grant funded, which are photograph collections. Right now I’m transitioning this through a collections management system, which will be [on] a public website. Right now there is no catalogue online. You can’t look online and access our collections at all— there is hardly anything. The best part of moving is that I am digitizing a lot, but it’s in bits and pieces. I want at least one image for every collection, mostly so that the website has visual content. But it’s patchy. Before this we didn’t really have a secure server to store digital files. Now we have a new server—it’s a work in progress.

SNL: I can imagine. In terms of searchability, or how you organize things, how is everything situated in here?

ML: Archival collections are organized by person. For example, you have, Fakir Musafar’s [collection], which is all of his artifacts and papers. However, we have a lot of artifact donations that are not associated with a specific person. A poster from an event isn’t necessarily a personal record, so those are organized by format. So we have a poster collection, a leather collection—that is mostly how I [organize] things.

SNL: How do you envision the archive acting as a tool and/or resource for people in Chicago or elsewhere? What can be learned from interacting with these materials?

ML: So much! It really depends on what you want to get out of them. For our creative side and our arts side, and for artists who are working with sexuality and gender, contemporarily there is plenty of material to work with. But if you’re working with something that is more historical, like the 80s and representation of sexuality, then you really have to get into private material.

There are not a lot of places to go for LGBT archives and, even more specifically, sexually explicit material and material relating to kink or fetish. A lot of that didn’t really make it into LGBT archives. For example, Etienne painted these big, beautiful murals and has a massive art collection here. They couldn’t find anywhere to take it as a collection, as it was sexually explicit due to content. For people who are working with those themes, there isn’t a lot of places to go to get that material where it’s been preserved and accessible. Even in more bigger institutional museums, sexually explicit material is censored or restricted. Sometimes it’s by the family’s request and sometimes by the institution, whereas we don’t apply any institutional restrictions like that.

The Chicago Archives + Artists Project (CA+AP) is part of Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art exploring Chicago’s art and design legacy, with presenting partner The Richard H. Driehaus Foundation. The project is funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art and The Richard H. Driehaus Foundation.

Featured Image: Image courtesy of the LA&M, Mistress Syd Creighton Scrapbooks, 1993. The image show a group of people walking in the streets outside. They are wearing leather gear, hats, vests and jackets. Four central figures have one arm up in the air and are walking towards the camera.

S. Nicole Lane is a visual artist and writer based in the South Side. Her work can be found on Playboy, Broadly, Rewire, Healthline, and other corners of the internet, where she discusses sexual health, wellness, and the arts. Follow her on Twitter.

Photo by Devon Lowman.