Movement Matters investigates work at the intersection of dance, performance, politics, policy and issues related to the body as the locus of these and related socio-cultural dialogues on race, gender, ability and more. For this installment, we sit down with movement artist, curator, poet and Queer Blq Futur narratologist J’Sun Howard to discuss the influences of geography, the role of joy in combating disillusionment and the importance of placekeeping and other practices in the life and work of Chicago’s black and brown artists.

Michael Workman: You don’t hail originally from Chicago, correct?

J’Sun Howard: No, I’m originally from Chattanooga, TN. I came here in 2001 to go to school at Columbia College. Here, I started out on the West Side. Then to Lakeview, which was fun, crazy, and full of self-discovery. Uptown was chill and where I began to feel more grounded. I went back to Lakeview after that, and by twenty-three I was done with the bar/club scene. South West Side in the ‘hood, around the Homan Square area was next, I would carry a small blade in my mouth in case I had to defend myself. It wasn’t the safest place I’ve lived. I got Humboldt Park but I didn’t feel like home after my two closest friends, Margaret Morris and Angela Gronroos, left. Now that I’m in Pilsen, I wish I’d lived here all along. I don’t think I would’ve struggled so much with how much rent is here. But I feel like I need a break from Chicago and to spend a couple of years elsewhere. I’ve been thinking about cities like Oakland, Portland, New York City, Philadelphia, Berlin, Lyon, Kobe, or Tokyo. Maybe I’ll do graduate studies in one of these places after I finish my undergraduate degree at the School of the Art Institute.

MW: Where does the interest in dance come from for you?

JH: Well, growing up I was never like, “I want to be a ballet dancer,” or anything like that. I was one of the kids who would record and watch the ’90s Hip Hop and R&B videos to learn the choreography in them, like Janet Jackson, Michael Jackson, Missy Elliott, Aaliyah … I knew there were people who do choreography but didn’t think or research it as a viable career. At the time, I was interested in being a biochemist or an accountant. I know, strange options, but I think those things still are active in my creative work somehow. My senior year in high school is when I decided to abandon the normative, cyclical 9-5 system and actually follow a dream to be an artist, i.e. a poet. I was more comfortable with words than with this idea of my body having words then. When our high school, City High, switched to a magnet arts one, Center for the Creative Arts, I chose Creative Writing as my focus although I did participate in the dance/step team. I wouldn’t say I was afraid of being in the dance program; I didn’t know where to begin. I guess I could’ve asked but it all seemed a little too late. During an award ceremony my senior year of high school, just after I received the last of three, this one for creative writing, I chose dance. The decision was abrupt and it was right.

MW: Who would you say were the biggest influences or mentors in terms of the work you make now?

JH: The only Hip Hop choreographer I say inspired me was Fatima Robinson—highly underrated. Many of the ’90s Hip Hop and R&B videos were choreographed by her. Her playful yet sensual nuances, idiosyncratic rhythmic choices, and the embodiment of narrative in her work were able to guide me in dreamscapes with these music videos. In that regard, I try to make dreamscapes with my choreographic work too. In order to get somewhere, you have to dream. Otherwise, what’s the point? I didn’t have a mentor in high school or the three two and a half years I was at Columbia College. I do wonder how my journey would’ve changed if I had. To see a black male be a poet or choreographer and learn from them would’ve been an asset and miraculous to my artistic growth. Bill T. Jones was an inspiration, but by the time I met him or went to take one of the intensives, I had already decided to not dance in a company. I knew I wasn’t that kind of dancer. When Jones’s company visited the Dance Center in 2003, I asked him about mentoring me but he disclosed an unfortunate experience he had mentoring someone and decided that he wouldn’t do it anymore. In the dance department at Columbia, I’d say Krenly Guzman was the dance teacher I gravitated towards the most. I took his class every semester. The quality, sophistication, poeticism, and lushness of his movement style captivated me. My goal was to transmute all of that in/onto my body. Of course, I’m still working at it. Spirals seem to get away from me. During this time, I didn’t know the kinds of work I wanted to make. They were experiments to uncover what’s in my voice. I’m a quiet person and also wanted to see what waited/waits behind that. For Student Performance Night at the Dance Center, one piece I did called “transmigration: a suffusing coalescing flight.” I think it was the only successful choreographic project I did during my time at Columbia because it felt like I was finally opening. And flight is a theme I continue to go back to, exploit, subvert, and re-imagine. Today, he probably doesn’t agree with me, but Darrell Jones is my mentor. I don’t know how to attest to how much depth, rigor, and sublimity has permeated my work from our movement research and collaborations.

MW: That’s great, it’s true. Dreams are so essential to that process. Where do you think you and your work are today?

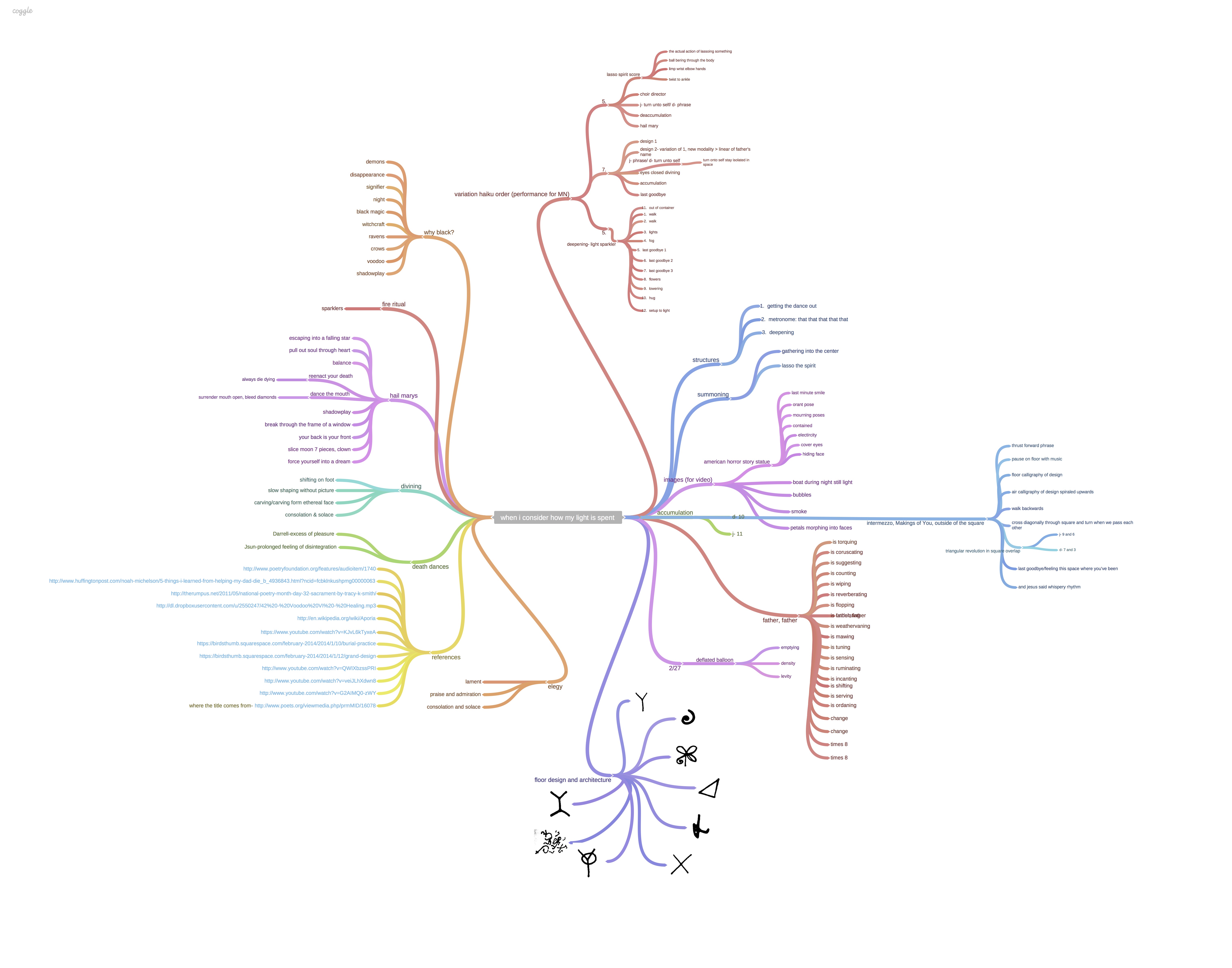

Where am I at today? Hmmm, well, the solo I put on Damon Green and the piece I’m about to make through Links Hall’s SET FREE Residency this year can be compartmentalized in Queer Blq Futur Narratives. But the cartography of everything I’m doing falls under what I call “poetic testimonies.” How I (or we) bear witness to the troubles and brokenness of this dimension. I don’t think I’ll stray from making poetic testimonies. But the challenge will be making them, or iterations of them, that are impactful, touching, and speak to the current times to come. I’m interested the idea of the future because it can reveal what it means to survive and evolve. Even though there are a lot of visual artists now like Nick Cave, Krista Franklin, Hebru Brantley, and Rashid Johnson working in AfroFuturism, I want to see how it can transmute into a choreographic lens specifically from a person of color’s viewpoint. I don’t call myself a visual artist but I drew this self-portrait as an Anime character and have been thinking how being a monster (as the media has portrayed black men to be) is a modality of survival. And why do I always have to be strong? On the flipside of that, I’ve been thinking about joy and how to use it to make dreamscapes that are charismatic and euphoric. (I know, an enigmatic dichotomy). Joy is important to seek out these days, knowing where our country is going. It’s a form of resistance. So why become a wounded bird that’ll land on anything? Moving forward, I want to devise work that creates new paradigms in which queer people of color not only survive but thrive and become magical birds. These landscapes aren’t going to be constructed for us, so seeing them performed can give folks perspective doing it in their real lives.

MW: Is it important then for you to try and move towards innovation in your work, or do you see it as relying on, say, poetic traditions?

JH: I try to not think that I’m innovating, which may be a way to be innovative. I trust that whatever I’m making has the merit to stand on its own. Since I’m a rare black unicorn in the dance community, I try to make things that a rare black unicorn would. I don’t know if this is a game or (again) a survival tactic, but I try to not think like everyone else and push myself to be unique and fuel my curiosity to be at the edge of something. When I think about artists who are my contemporaries, I can count them on one hand in Chicago, which is quite problematic. It doesn’t bring me to the forefront either. It’s as if there’s enough room in the garden for a flower to bloom in the shaded area no one really wants to take notice of. When I look beyond this city, artists in NYC like Ni’ja Whitson, niv Acosta, NIC Kay, Rashaad Newsome, Brother(hood) Dance! (Ricarrdo Valentine and Orlando Hunter), Niall Niall, Jonathan Gonzalez, and many more are all fabricating these constellations I see my work in relation.

MW: In terms of what you’ve accomplished in your work so far, what do you see as having been the most successful?

JH: To date, my most successful artistic aspiration was being selected for the Chicago Dancemaker’s Lab Artist Award in 2014. It was affirming, especially as an emerging artist. I applied on a whim. At the time, only my close friends knew I was ready to quit this artistic journey. I was ready to delete my social media accounts, change my phone number, go back to Chattanooga, and start completely over. I was fed up with seeing work that was uninspiring or a complete waste of time/effort, I got rejected from everything I applied for up until then, and any work that I found wasn’t worth the hustle. I don’t know which diviner decided to cast a string of gold my way just enough, but I’m still here. In that sense, what has worked has been forging forward and trusting my creative work will lead me to places I’ve never dreamed of going. Patience is vital. But sometimes patience feels like a con. So I started reaching out to people I wanted to collaborate and/or work with. I asked Thomas DeFrantz if I could do a residency at Duke University, and in 2018 I’m going there to work in the SLIPPAGE laboratories for a couple of weeks. I stopped waiting for rejections (they still invade my inbox though) and discover ways to make it happen on my own and with the help of admirers of my work. I do have goals like becoming a Princeton Fellow, doing a Lannan Residency, winning a Bessie Award for Choreography, a Doris Duke Artists Award, and an Alpert Award, or just being commissioned for the Lyon Opera Ballet to name a few, but I know I’ll get these one day. I often wonder how my artistic career would be different if I had a BFA and MFA, but I can check back in with you when I have them.

Credit: Courtesy of J’Sun Howard.

MW: Where does identity fit into your work for you, if it does, and what’s necessary to push back against a system that often unnecessarily problematizes depictions of the black or brown body in dance?

JH: I kind of get irritated when I have to answer a question like this. I or people who look like me aren’t the problem. I can say how a lot of the times, I feel like I’m a mouse being coaxed with just enough crumbs to be comfortable inside a labyrinth that supposedly has exits. There’s all these panels, symposiums, think pieces, scholarly papers, and social media battles on how to dismantle white supremacy, but white people don’t want to do the work that takes to dismantle it. Talking in circles, circles are labyrinths. So who’s afraid of taking one for our team. Black bodies do it daily. To go against white supremacy, I do rituals that make me feel whole and connected to nature/others. From preparing a delicious home cooked meal, long walks, getting lost, staying up all night thinking about holy things, writing poetry and reading poets like Danez Smith, Jayy Dodd, Morgan Parker, Clint Smith, Paul Tran, Ocean Vuong, Kaveh Akber, Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib, Roger Reeves, listening to podcasts like The Read, 2 Dope Queens, the Friend Zone, PostBourgie, Helga, Ignorant Philosophy, laugh at myself, watching my niece Chloe grow up, traveling, making sure I give hugs and tell people close to me I love them and so on and so on. To go against white supremacy, I have to live how it doesn’t want me to live.

What I think dancemakers of color should start doing is creating institutions for investigation and incubation. Even though Theaster Gates receives criticism for the work he’s doing on the South Side, he’s an example to follow. I’m going to apply for the ArtPlace National Creative Placemaking Fund because it would be significant and crucial for Pilsen to have a space dedicated to movement research, choreographic inquiry and performance alongside the many art galleries here. “Placekeeping” can be a way to combat the gentrification that’s occurring in Pilsen. Plus, this space can be curated in a fashion that can reinvent and change the current model to promote dancemakers of color better than other institutions have. In addition, organizations and non-for-profits around Chicago should analyze data from the past eight to ten years to see if their programming was diverse, equitable. I can tell you from experience that most aren’t. For us, by us is imperative if we want to see change. I hope Damon Green’s dance studio, TextureDance, is successful and becomes influential in Chicago’s dance community.

And then there’s education, and how the economics of it is violence towards people of color. Many people of color decide not to pursue an art degree because there isn’t money in it. And in order to contest the economic violence, you need a salary that will uproot you from the stagnation the system causes. I know some younger folk who don’t want to go to college because they’re afraid of having “good” debt. Most artists making their way through the dance/performance world go through this step by step acquisition of merit from one award/grant/residency to the next. And within this structure, it hardly ever recognizes artists who have not acquired an MFA degree. Yesterday, on Facebook an organization I follow for scholarship opportunities posted Milo Yiannopoulos has a white privilege scholarship for white male undergraduates. I could only laugh, and hope it was a joke. Many dance departments at college and universities should have full rides, fellowships, and emergency funds to ensure their students not only reach their potential but surpass it. Retention of students is a major problem for art schools, but I still don’t see anything being done to remedy it. Returning to SAIC, knowing that admitted students get merit scholarships, would mine increase since I’ve received more merits? People think art is an easy thing to do but it’s only easy when you don’t have to worry about living.

MW: Those are all important insights. Thanks so much for taking the time to have this conversation with me. Any last thoughts before we wrap up?

JH: Promoting and curating queer emerging artists of color is becoming more immediate in my artistic practice because of the lack of programming I see around the city. And it helps equip the generation after me to do better than I did.

MW: Thanks, J’Sun. Very much looking forward to seeing that work!

Please also feel free to send questions, comments or tips to Michael Workman at michael.workman1@gmail.com. Each Spring and Fall, as a corollary to the Movement Matters columns here at Sixty, we also present a series of symposia and performances at different locations throughout the city based on topics developed out of and indexed from both the columns and live discussions. Upcoming symposia include Invisibilia at Mana Contemporary’s Body + Camera festival on May 21, “convened to examine the topic of immateriality in art-making as a response to traditional power structures in the dance and performance art worlds, and how it arose at a time of the recognition of a pushback in social movements against ‘invisibility’ and erasure in the larger culture.” Body Politic will also be followed that evening by a performance at the Mess House home dance and performance series, with Chicago choreographic collaborative The Coincidentals. Please join the Movement Matters Facebook page for any additional forthcoming dates and times, archives of Facebook Live broadcasts of these discourses, and to join in on future conversations.

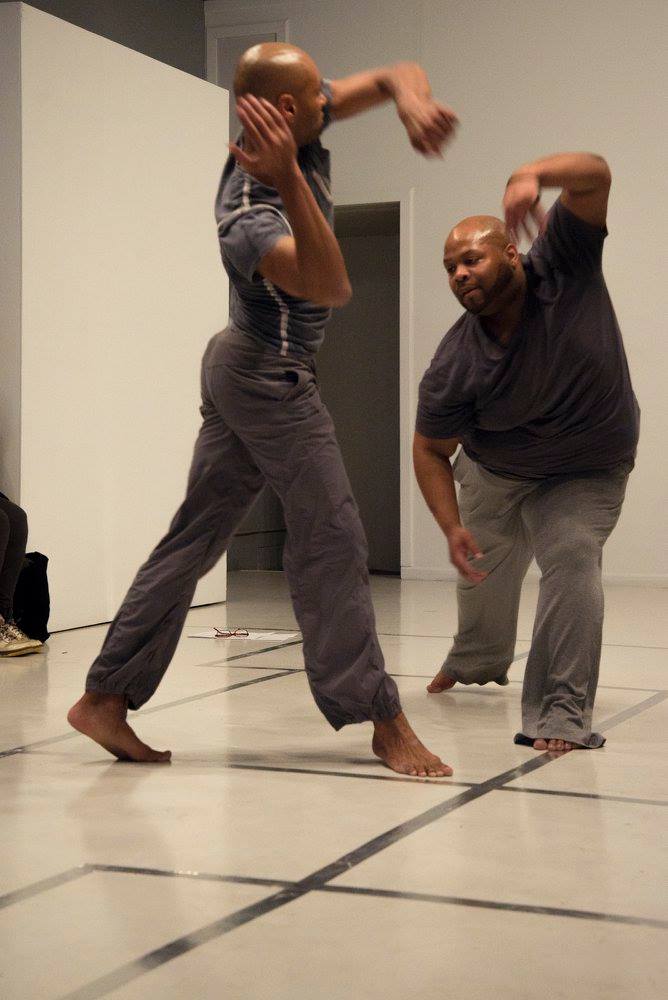

Featured image: 2014 CDF Lab Artist project “When I Consider How My Light Is Spent” Credit: Kiam Marcelo Junio

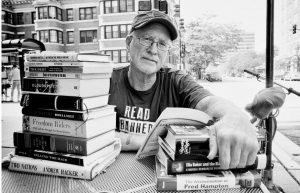

Michael Workman is an artist, writer, dance, performance art and sociocultural critic, theorist, dramaturge, choreographer, reporter, poet, novelist and curator of numerous art, literary and theatrical productions over the years. In addition to his work at The Guardian US, Newcity, Sixty and elsewhere, Workman has also served as a reporter for WBEZ Chicago Public Radio, and as Chicago correspondent for Italian art magazine Flash Art. He is also Director of Bridge, a Chicago-based 501c(3) publishing and programming organization. You can follow his daily antics on Facebook.

Michael Workman is an artist, writer, dance, performance art and sociocultural critic, theorist, dramaturge, choreographer, reporter, poet, novelist and curator of numerous art, literary and theatrical productions over the years. In addition to his work at The Guardian US, Newcity, Sixty and elsewhere, Workman has also served as a reporter for WBEZ Chicago Public Radio, and as Chicago correspondent for Italian art magazine Flash Art. He is also Director of Bridge, a Chicago-based 501c(3) publishing and programming organization. You can follow his daily antics on Facebook.