Using a title borrowed from an essay by cultural critic Mark Dery, the Black To The Future Series is a sequence of interviews with artists whose practice has started to define a new generation of work in the realm of afrofuturism and afrosurrealism. Using a pointed series of questions, these interviews have been conducted to spark conversation, to hear various points of view on something that is constantly changing and transforming, and with the hopes of allowing the practitioners to be at the center of determining what these movements are.

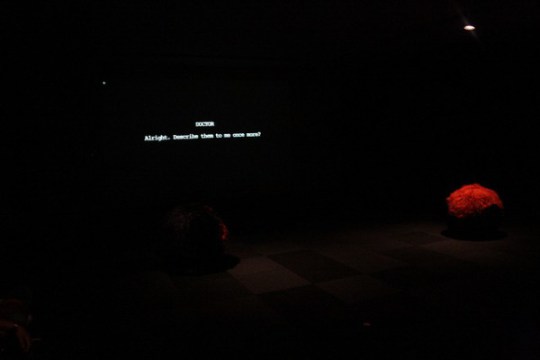

This week we get some insight from artist and filmmaker Cauleen Smith. Cauleen has spent the past two years in Chicago researching and digging through the Alton Abraham Papers at the University of Chicago and music archives at the Experimental Sound Studio to find gems from the life of musician and philosopher Sun Ra, a key figure in the conversation around afrofuturism. The results of her investigation can be seen in A Star Is A Seed, an installation and series of short films at the Museum of Contemporary Art, and also in The Journeyman, an installation that will transform threewalls into a temporary library, a space for music-making and an opportunity to glimpse into her process and the fruits of her labor. In this interview, Cauleen speaks about the artists, filmmakers and writers who have influenced her over the years, language as material, the magic in the science of Harriet Tubman and George Washington Carver and her thoughts on the momentum behind the afrofuturist movement.

Tempestt Hazel: Do you consider yourself an Afrofuturist, an AfroSurrealist or both?

Cauleen Smith: I’ll be honest, I find the modulations in these definitions a bit tedious. I am very engaged with the ideas generated by the afrofuturist discourse and I spell it with a lower case “a” because for me, it is not a moniker of identity or geography but a musical, literary and art historical movement – like creative music, post-modernism, or conceptual art. Afrofuturism, like these movements, offered a lot of room for challenges, variations and growth. Since this was the term that helped me define some aspects of my work, I’m happy to stick to it and learn about afrosurrealism from others who are really invested in new pathways. My investment in history, science, speculation, and cognitive estrangement rather than psychoanalytics, the abandonment of reason and language, the inculcation of the paranormal, etc. make afrosurrealism a less active strategy for my own art and filmmaking even while I learn a lot from these strategies (and love the manifeto!) and quite enjoy the works that seem to fit into this terrain, like Tutuola’s Palm Wine Drinkard (a personal favorite).

Moreover, before I began following and learning from the afrofuturist crowd, I was already a speculative fiction head. One of the more famous quotes from one of the more famous mid-twentieth century sci-fi writers, Arthur C. Clarke, was, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” This is the third of his oft quoted “three laws.” One of my favorite films, Yeleen, (directed by Souleymane Cissé, 1987), tells the mythic travails of a young wizard in ancient Mali, who must summon enough magic to defeat his own father. The most wonderful thing about the film for me, aside from the wonderful mise-en-scene, pace and art direction, is just how procedural all of the magic is. There are set materials combined in specific ways to produce specific results. These results appear to be fantastical, but to me these magicians could be understood as scientists. This is the kind of tech- ancient African tech, that I’m really into: Harriet Tubman’s navigation system, George Washington Carver’s plant empathy. To me this is all afrofuturism.

TH: How do you define Afrofuturism?

CS: Well, black geeks have been collecting, cataloging and just plain dialoging with science-fiction tropes in hi and lo art for as long as I can remember. I first met Greg Tate back in the mid-nineties after the seminal Flyboy in the Buttermilk offered us a primer on how to locate the radical center of black cultural production and one of the first things we talked about was comic books! And I still remember the rush of recognition that I experienced when I first read Mark Dery’s description of a pattern that he gleaned in part from conversations with Tricia Rose, Greg Tate and Kodwo Eshun among others, in the practice of art in music within the African-American cultural lexicon. I’d made this film, Chronicles of a Lying Spirit By Kelly Gabron (1991) and I didn’t really have a concise way of talking about what I was trying to do, both formally and narratively, until I had this framework of afrofuturism.

Put simply, I would describe afrofuturism as the experience of cognitive estrangement as manifested through sound, image, language and form that so often defines or frames the mundane conditions and movements and generative thought in the African Diaspora. And here I must confess that I certainly conflate all manner of analysis from the above mentioned thinkers/artists as well as Erik Davis, Darko Suvin, and Samuel Delaney to name just a few major influences to my way of thinking about making work through this lexicon of afrofuturism.

TH: What do you feel are the biggest misconceptions about Afrofuturism?

CS: I think one concern I have about the way in which afrofuturism is so gleefully applied to any and every article of black cultural production that blithely references “space” or “technology” is that it really obfuscates wonderful opportunities implicit in this practice, like the challenge to generate actual forms that reveal the experience of cognitive estrangement and applications of technology and speculations on the future-past as images – as sounds – as spaces – as forms. The bebop artists of the fifties, just like Sun Ra, gleefully joined in the American exuberance of the Cold War space race. However, Sun Ra moved past the mere titling of songs as space-objects into an actual research and philosophical practice invested in the liberation of the mind through sound, technology, language and history. I realize that’s a bit didactic. Greg Tate gives me bountiful mess about my fascist attitudes all the time, but at heart I’m a formalist. So for me it always boils down to the application of ideas as they relate to materials.

TH: Do you remember when you first became aware of Sun-Ra?

CS: Not really. I’ve been a devoted jazz fan since I was a wee teen. But the real revelation for me came at 2006 or so when I learned that he formed his speculative identity in Chicago – that he had a long incubation period (about 14 years) in which he research, practiced, labored, and became Sun Ra. The ephemera and private recordings that were rescued by John Corbett from Alton Abraham’s (Ra’s business manager) basement after his death has been so instructive to me regarding Sun Ra’s DIY creative and business practices. I so enjoy the way in which he stitches together a future-techno-African imaginary with mundane objects. The real and the myth are constantly destabilizing each other in the same way that – to me – Sun Ra melodies are most often spiral structures.

TH: What is it about his philosophy that resonates with you?

CS: Where to begin?! I hadn’t realized the extent of Sun Ra’s historical and even linguistic research until I got into the U of C archives. As a lover of the way in which words can enable us to precisely articulate our interiority, Sun Ra’s play with words really intrigues me. Just as many artist try to use forms to revise or repair historical and social blind spots, Sun Ra thought of language as a material with form and did not distinguish it from sound, or color or performance for that matter. All senses intertwine as one through his writing. Another thing that I have enjoyed trying to tease out of the archives is his deep interest in young people. He write a lot about his concerns over the youth and there are some great recordings in the Experimental Sound Studio Sun Ra Archive of Sun Ra patiently and humorously talking with students.

When he does this, he never panders or dumbs down his cosmological philosophies. Rather he obscures in such a way, I suspect, to generate a kind of unsettling curiosity in his young listeners. I like anything that provokes curiosity!

TH: The career and influence of early 20th century artists and later Sun Ra prove that the principles of these movements were relevant decades ago. But what do you think it is about this moment that creates an environment which is conducive to a magnified resurgence of these philosophies as well as the receiving, uplifting and celebrating of these ideas on so many levels by artists, institutions and scholarship alike?

CS: I don’t really know other than perhaps it has something to do with the fact that the people who initiated this conversation almost two decades ago are all pretty much now, career artists and scholars in a position to share (publish/distribute/press) our ideas and research with new generations in this way that has a pretty solid form. Fifteen years ago the afrofuturist conversation was threads and strands interconnected like a lace of spiderweb. Now the ideas have hardened more into something that can withstand more play and pushback. Afrofuturism as a movement is a great vessel for imagining the alternatives to contemporary life that we so desperately need to combat the continued cultural hegemony offered by mass-distributed pop culture.

TH: What are the current questions and explorations in Afrofuturism adding to the dialogue that has already happened around these concepts and ideas?

CS: I can only speak for myself when I say that I feel very grateful to have stumbled upon the afrofuturist concept as a creative device that could be fused with any number of philosophical or material questions that I might have as an artist. And I look forward to the ways in which its application goes viral and becomes a fundamental and therefore less fashionable component of creative discourse. As a tool it is a wonderful thing. As a trend, it can be a little more worrisome. That’s when I pull Samuel Delaney off the shelf and remind myself of what can be at stake in these ideas.

TH: What is different about these movements today that perhaps don’t align with the historic concepts of the past that have served as an influence and foundation for it?

CS: I am very happy about the way that the influence of women like Tricia Rose, Nalo Hopkinson, and Alondra Nelson has not been shunted aside in favor of the usual male-liberation theology that overtook (and undermined) the political and creative movements of the past. Afrofuturism owes as much of a debt to feminism as it does to technology. This is why it has remained such a useful component of my praxis. Also afrofuturism is the first, I’m sad to say, black creative movement that wholly embraces queerness. For how can we speculate about the self, the body, otherness, and resistance without looking at, listening to and learning from the accumulated wisdom and alterity of queer history and culture?

Moreover, look at the unstable gender performances and aggressive feminist assertions that are so prevalent and important in afrofuturism, from LaBelle – the soul- free jazz fusion project of Pattie La Bell, Nona Hendrix and Sarah Dash. Grace Jones’ fearsomely androgynous representations of sexuality and the body politic. Even Mary Lou Williams, mentor to Monk, Miles and Bird (to name a few) applied an astrological structure to her wonderful Zodiac Suite. I could even take it back to Zora Neale Hurston’s amazing anti-ethnographic films that she shot on a newly portable 16mm format (hi-tech in its day!) in South Florida for Boaz. She created images that now exist as a call and echo for the future-past of black life both rural and urban. So for me the biggest difference is that women and queers are central to this movement. As it should be.

A Star is a Seed will be showing on the MCA Screen through September 16, 2012 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. The Journeyman opens September 7th at threewalls and runs through October 20, 2012, with two musical performances at threewalls on October 3 and October 17.