“We are excruciatingly conscious of what it means to have a historically constituted body.” – Donna Haraway

In the early 20th century, women artists worldwide such as Suzanne Valadon, Paula Modersohn-Becker, and Romaine Brooks began to work extensively with the feminine body as subject. They averted the gaze away from hetero-masculine fantasies and fetishes to their realities: their bodies and their experiences in those bodies, often set in spaces with other women.

Valadon eschewed the critical judgment reserved for her upper-class women contemporaries because of her working-class status and reputation as a sexually available artist model. She painted nude portraits that showcased other working-class women and emphasized the context and action over nakedness itself. Yet most recall Degas’ baigneuses, not Valadon’s; even more forget Valadon altogether.

In some of the most “progressive” Western art movements years later, take Surrealism, many women artists were forced, still, to enter artistic circles as models or muses first and/or by way of male romantic partners and then to wrestle with the shadow cast over them and their work by those men throughout their careers.

Around the same time period, women were becoming a coveted target demographic. Fashion and cosmetic advertising campaigns projected a glamorous image of the elite “New Woman” to the masses and, along with it, empty promises of wealth and luxury that profited a select few, namely the men already controlling the means of production.

This February, I could barely get out of bed. My job was taking and taking from me. I was struggling to write. (And it was the dead of February in Chicago.) So I turned to photos. I took a documentary media class with O. Kristina Pedersen at Lillstreet Art Center and attained punctum once again, that element, that pinhole that collapses time and transforms art into an immediate emotional connection. I felt it in Pedersen’s images and those produced by my classmates and started to see it around me, this disruption of the daily slog of media, a glimmer in the fog of the grind. That’s when I first encountered Glamour Girl.

In 2015, Glamour Girl (GG) magazine started as a reaction. Against financial barriers in the art world. Against the push for supreme digital rule. Against glamour. The idea was conceived on a Chicago summer day and arose like heat from a stockpile of disposable cameras discovered at the Salvation Army by Giselle Gatsby (also, I suspect by no coincidence, GG). Gatsby is editor-in-chief and artistic director and her lead interview and copy-editing partner is Ines Kovacevic Gill, who is based in London.

Gatsby sought to “showcase the unedited, raw imperfect realities of what it is to be a woman artist, in their voices.” She mailed cameras to the women artists she knew with instructions to document their realities. Since then, there have been countless connections made between women artists in Chicago and around the world, documented in six editions of the independent publication.

“I don’t think I would have been so compelled to do this project if I didn’t feel like women as artists, and just as existences, weren’t underrepresented,” Gatsby says. “There are platforms, but a lot of them require monetary things for submissions and grants and it’s kind of criminal: you spend all this money on education, trying to access these parts, but then you still have to apply to a bunch of grants, spend money, and hopefully you get seen or are seen.”

Each issue of Glamour Girl replicates the DNA of the first. There is a vision, a theme. Then, Gatsby and Kovacevic Gill reach out to artists they admire and hear from some secret admirers to assign in-depth interviews, photo essays, profiles, and experimental pieces. Photo shoots are orchestrated, some with ample prep time, others rigged together and finished right before a flight departure. There is the design work on the computer, then every page is printed and laid out for Gatsby to scrutinize, walk through, and accept as complete. “It’s never finished,” she says, “I know the sixth book is out, it’s done, but I feel like it’s still unfinished, the pursuit.”

Glamour was derived from Scottish English in the 1700s to mean magic, enchantment, or witchcraft, the latter of which has seen a reclamation in more recent years. Some contemporary feminist activists still look to the witch, a femme persecuted for defying patriarchal authority through the ages, as a protector.

Before this Scottish permutation, during the Medieval period, glamour shared a similar definition with grammar. The Latin grammatica encompassed all learning and knowledge – period placement, scholarship, necromancy, Faust. In a Europe starkly divided by class, the rich and educated, literally speaking their own language, were not to be trusted.

In the more recent past (the 19th century), glamour came to be perceived the way we think of it today – attractiveness, sex appeal, illusion, Grace Kelly, soft focus, Fergie.

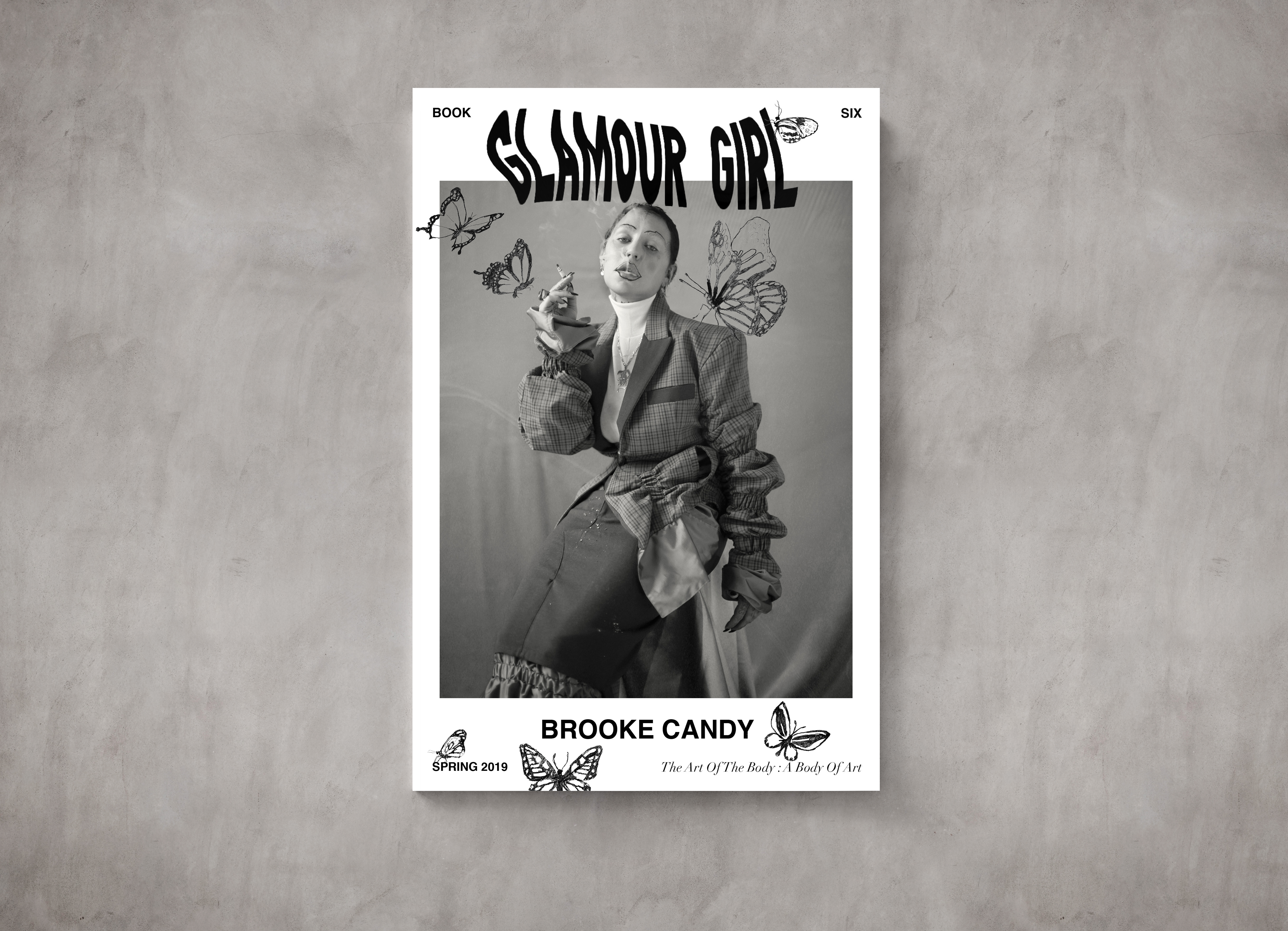

The sixth iteration of Glamour Girl, The Art of the Body: A Body of Art, released April 2019, enchants the beholder. On the rack, the book could be mistaken for a high-fashion magazine that’s been doodled upon with butterflies, which is part of its charm. Open it to witness skin become canvas, dance channel spirits, stone eternalize youth.

The issue appears to travel across generations, starting with a love letter from performance artist Marie Ségolène to Charlie She, a queer, polysexual, femme, multidisciplinary artist and activist who uses their body, voice, and sex appeal to destroy the patriarchy “one selfie at a time.” It concludes with Hereditary, a photographic epitaph by Vincent Joseph Marcinelli dedicated to the last year of his first-generation Italian-American grandmother’s life. Marcinelli’s images dote on his grandmother’s hands, which he considers descriptions or stories passed down to his mother’s hands and then to his.

Although the GG mission is not to highlight artists who already have large followings and platforms, cover girl Brooke Candy lives the Glamour Girl philosophy and theme of the sixth issue. Candy, covered in hundreds of tattoos, speaks in her interview to the carnal power of the feminine body, of which she has a CV of expertise: a film collaboration with PornHub, career in stripping, and family tradition of work in the porn industry. She also touches on her nostalgia for the Old-Hollywood-style excess of sex symbol Anna Nicole Smith. Candy’s saunter into the media limelight started in the music industry with her cameo in Grimes’ “Genesis” video and she has continued to harness light beyond her own practice from subsequent collabs with pop sensations Sia and Charli XCX. Her feature in the magazine marks a new level of visibility for Glamour Girl.

While some GG6 artists hone in on the feminine physical body as sexy or soft-beautiful, Jasmine Mendoza’s featured work is only achieved when she moves her body to transcend her physical form, however awkward the angle may be. A Chicago-based, Mexican-American movement artist, Mendoza has been practicing Butoh and BodyWeather, Eastern traditions of dance in which the body acts as a vessel to communicate some natural image or expression. “It is an attempt at true freedom for the body and the spirit, an exploration of the infinite that exists inside a millimeter of movement,” writes Chicago artist O. Kristina Pedersen in her rumination on the artform. Chicago photographer Alexa Viscius captures Mendoza’s frenetic movements in black-and-white film. Underneath this story about Mendoza’s practice lies the relationship-building at the heart of Glamour Girl, this time in a local network.

When I meet Gatsby in the flesh, in front of her Wicker Park loft, she is wearing knee-high boots and a long, dark blazer, unbuttoned down from the waist of her cut-off denim shorts. Clear, lucite bracelets (her design) dance around her wrist. (She’ll take them off later when the tempo of her movements escalates.) Before we chat further, we cross the Six Corners for a coffee at the Damen-Blue-Line-stop’s La Colombe. Naturally, we bump into Caitlin, one of her muses. Gatsby tries to recruit Caitlin for the Virgil Abloh collaboration she’ll tell me about later. It makes sense Giselle Gatsby’s initials are identical to Glamour Girl’s: GG cannot be understood without also taking in the entirety of what she has created.

“I’m like a spider,” Gatsby tells me, “in a big web of cool women that I get to be a part of and be able to facilitate projects and help make their dreams possible.”

Glamour Girl is an art book, but, more critically, it’s a global art network. Muses, artists, photographers, and writers from the Canary Islands, France, New York, and next door collaborate for GG projects and will likely continue to connect and work together beyond the pages of the publication. Like Riot Grrrl zines before it, Glamour Girl manifests a feminist ethos to build a borderless community through connections to other femmes’ work, disrupt the status quo, and, ultimately, document a legacy for future femmes to model. And I wonder if that’s the never-ending pursuit.

Featured Image: Issue six of Glamour Girl magazine, The Art of the Body: A Body of Art. Image courtesy of Giselle Gatsby.

Amanda Dee is a Chicago-based multi-media creator with seven years of storytelling experience across art, journalism, nonprofit, and health organizations. She is also the associate producer of the oral history podcast Moral Courage Radio: Ferguson Voices, which documents voices from the Ferguson community in the wake of the 2014 police shooting of Michael Brown. You can find more of her work here.