I want to begin with memory; that seeping, oozing bedfellow––the comfort it wields beneath skin, between teeth––with smiles and cracked joints like damp carpet squished between cold toes. It is the sweaty aspic of sickly kaleidoscope color, eaten only by families of scrubbed blank faces and crinkled pages, but what’s that bite in the back of your throat? Maybe you feel it too, this ambivalent wonder and witness, your very own slice of gelatinous omen (Amen) pearling against a porcelain slick plate’s unearthly glow. Memory as a thing, a state of being, a mode of knowing, a sixth sense about the elephant in the room, the surety that this is not your beautiful house, the bird’s nest crown of your own private Idaho. Don’t get the chlorine in your eyes.

In 1966, historian France A. Yates wrote The Art of Memory, a study of memory’s role within human life. Yates contemplates memory and mnemonic devices through the lenses of history, literature, and philosophy, beginning with the story of Simonides of Ceos, the 5th century (BC) Greek poet. Simonides attends a feast given by a wealthy nobleman and recites a poem in honor of his host. Later Simonides steps away from the banquet for a moment outside. The nobleman’s palace then collapses. There are no survivors, except for Simonides. The guests’ friends soon come to bury the dead, but all are crushed beyond recognition by the building’s debris. Only Simonides recalls the seating arrangements within the palace hall where he recited his poem; he identifies each guest for their mourners. This is the western birth of the “memory palace.”

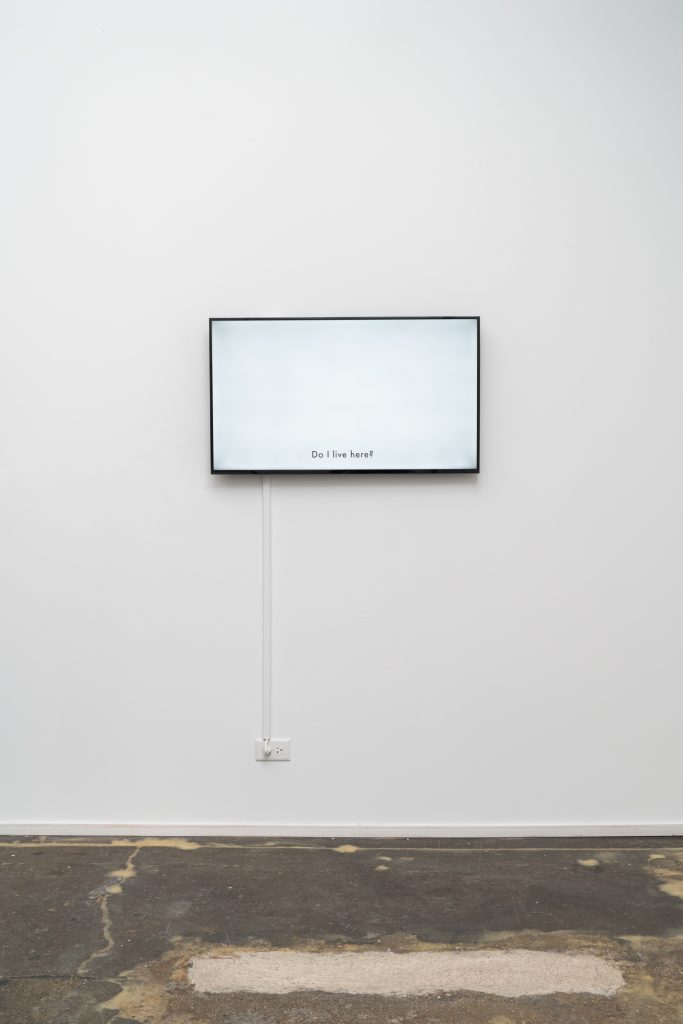

Memory is an architecture, both your home and haunted house. You tiptoe carefully around bombs underneath floorboards, daily practice has made you an artist; squeaks, held breathes, staccato footfalls, and silences sing with pristine, glass-cut sincerity as the body moves in and out of syncopated time. Think Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, the power of everyday performances and what happens when those performances end: boiled potatoes, work, a dropped spoon, sex, death, the spiral of an ending and beginning. It is the weight and release of the mundane inscribed within the whorled hearts of braids, the sculpted lines of collage, the photograph’s frozen moment, the curl of a body burdened, a body in flight. Memory, both of the body and beyond the body, is what we carry, what we live; the gauze covered window where we greet each day.

Curated by Stephanie Koch, Chicago Artists Coalition’s Repository and Repertoire presents new works by HATCH residents Jazmine Harris and José Santiago Pérez. Created within the last ten months, Harris and Pérez’s works present the bodily intimacy of memory and making: what we touch, what touches us, and how we tell these stories of ache, permeability, and porousness during crisis. You, me, we: seven letters, seven rooms, seven poses, seven points of view, within and against seven and more and more and more, infinite breaks, intersections, and returns. Harris and Pérez’s practices are situated as guideposts within this composition, kin to the titular repository and repertoire, the performance of narratives and the body.

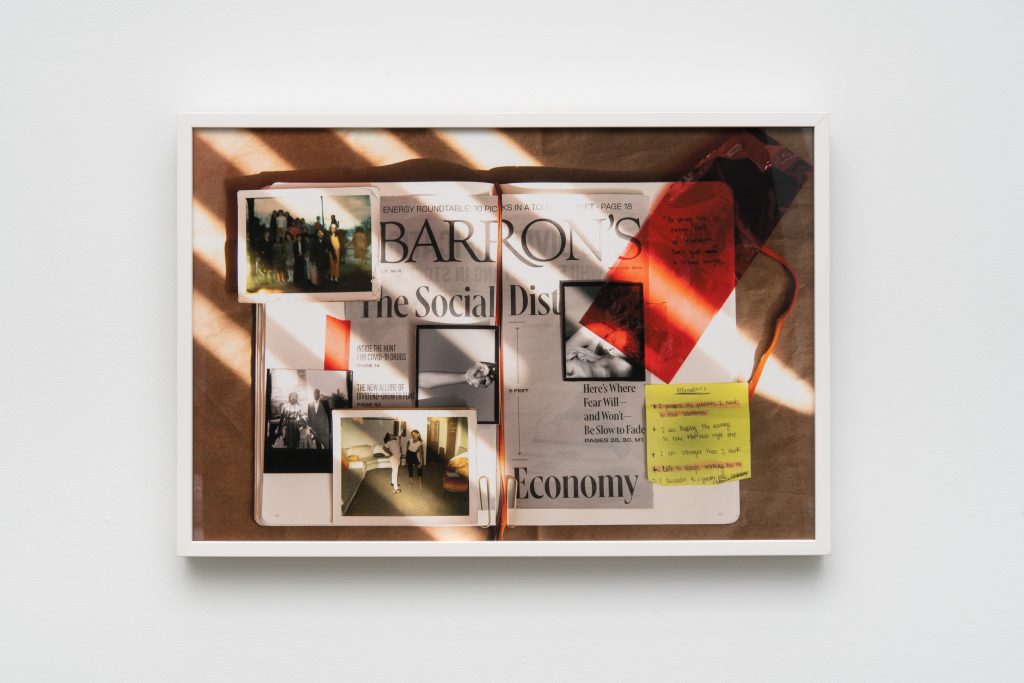

Harris’ work centers the artist’s personal archive against and within the matrix of large-scale political forces that have shaped the last year. She asks and answers: how can a person live, the simple, the mundane, the familiar, during ongoing emergency? Family photographs and Harris’ personal writings are simultaneously transformed and reaffirmed through collage and the intimate techniques of scrapbooking. It is the feeling of contentment, fingers smoothing pages while gently inhaling the room where the self is born, as white supremacy and capitalism fog our mirrors and window panes. In the virtual discussion Revision, a component of the exhibition’s public programming, Harris and Koch were joined in conversation with artists Sasha Phyars-Burgess and Cameron A. Granger. Here, Harris speaks of Breonna Taylor’s murder by the Louisville police department and the impact Taylor’s story has had on her as a Black woman moving through the world. Harris’ specifically focuses on Taylor’s love of scrapbooking: the importance of recording one’s narrative, the power of authorship, and the significance of young Black women as keepers of memories, of everyday stories of softness and quiet. Consider now Harris’ self-portrait, Untitled; the artist is center frame, her gaze above and to the viewer’s left. She sits at home in her grandparent’s chair while she has her hair done. In her hand is a remote shutter release cable. The seemingly candid image has been meticulously planned, lit, and posed; it is what you know and what you can never know.

In The Giverny Document (2019), filmmaker Ja’Tovia Gary asks Black women she interviews, “do you feel safe in your body?” Harris does not explicitly ask the same (though the anxiety of navigating misogynoir, unsafe spaces is present within Harris’ work), but rather she thinks through the questions of how one is to be in the world: who are you, who were you, what happens next? These ideas of knowing, making, and remaking through memory––illuminating and rearticulating midnight glossed pinpricks of the self––come to the forefront in Harris and Koch’s talk, Articulating Worlds: Interviews as Third Space, given as part of the University of Chicago Department of Art History’s Speaking of Art Roundtable Series. In Articulating Worlds, the very concept of the interview is considered: its boundaries, parameters, and the potential of its dialogue. What you say, what I say, what we say, what’s never said, comes together to build a room where the self is made and remade, again and again; if you don’t know, now you know.

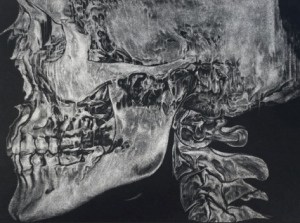

In José Santiago Pérez’s work––specifically his choreographies––a psychology of the glitch is made material, expanded, and metamorphosed through the body burdened, the body in rest, the body’s history. It is the knowledge of senses so deeply ingrained that the gestures, the movement, that much-rehearsed ever-practiced performance of a day, begins to make and remake you. In Glitch Feminism (2020), writer Legacy Russell theorizes the potential of disruption, nodes of departure and return where bodies of color, queerness, and time do not behave as white supremacy and capitalism dictate. For Russell, the possibility of discovery and making is centered in the concept of the glitch; the moment, the place, the state of being where the system does not act as programmed and something is created in its stead.

Pérez’s Unburdenings, performed in conversation with artists Kim Chayeb, Zachary Nicol, and Kai Shariq over a series of four live-streamed weekly rehearsals, tells the story of the body. Pérez asks: what does the body remember, how does it remember, what does it need in the face of harm? Unburdenings is a work in flux as it was conceived in response to an ever-changing pandemic. The performance sessions seek to exorcise the toll that neocolonial brutality, racial violence, death, and illness imprints upon the psyche. The performance rehearsals are arranged to encourage the viewer to leave and return to the stream, actions that attend to the force of the psychological material Pérez holds during each performance. Every day is different, a single cell where beginnings and ends no longer easily touch. Touch what pains you. Find the touch that comforts, that bears fruit. Throughout the exhibition space, pieces from Pérez’s sculpture series Un/Burden present points of meaning and making where change is possible, tongue and teeth scrape against every word.

The body is an archive: a hard drive, memorial, escape pod, Netflix queue, a bound of Gordian knots surrounding soft rooms. It is a study in pain, endurance, loneliness, a map to absolution anointed by yeast and neurochemical receptors perfumed with fresh cardboard and red dye number forty, the tinnitus buzz of a holy ghost in a sleep-numbed arm wrapped around your beloved. Each piece in Un/Burden is crafted in dialogue with the concept of burden baskets, our prayer boxes, sin eaters, receptacles for the collective good. Ceremonial and utilitarian, you drip into holes; shut the lid, lock the door. Pérez’s sculptures are woven with the same plastic––mylar––as NASA mylar emergency blankets, the trauma blankets of immigrant children “assigned” to American overflow facilities. It is the indeterminate made manifest under imperialism’s logic, what the system’s glitch can do. The thin line that separates crisis and comfort is not so much a line but rather a gesture: the tight coil of each sculpture’s rim, a curve of the body, a wave, a flutter, a bend. The story of the body is the most human of tales.

Time tastes different; temporalities feather, flatten, and expand. You brush your fingers against the narrative, your story held firm by scrapbook edges and the body’s coiled curves. Meaning is amplified, reconfigured, bloomed bright and full. This is a reflection, a gesture, a moment that forces us to consider what we know and how it’s known. Where do power, promise, and hope live? Where might you call home? In conversation with Koch’s curatorial work and programming, Harris and Pérez’s practices present the possibility of memory as performance, the body as archive, knowledge that excavates the self again and again. Perhaps these words might also fashion themselves into a collage, a performance, a house, a home.

Repository and Repertoire is up at Chicago Artists Coalition until March 11th, 2021. Please see CAC’s website more information on current hours and social distance protocols. This exhibition was partially supported by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency.

– – –

Featured image: Installation view of Chicago Artists Coalition’s Repository and Repertoire. José Santiago Pérez’s sculptural pieces Un/Burden (so you may release), 2020, and Un/Burden (so you may restore), 2020, sit in the foreground on a white exhibition plinth. The piece on the left is composed of light-pink coiled emergency blankets and plastic lacing. The piece on the right is composed of silver and purple emergency blankets and plastic lacing. In the background Jazmine Harris’ self-portrait Untitled is exhibited on the wall. To the left of Harris’ piece, is Perez’s, Un/Burden (so you may continue), 2020: two rimmed sculptural light pink and aqua-marine sculptural forms composed of the same materials. Photo courtesy of the artist and curator.

Annette LePique is an arts educator and writer. Her research interests include cinema, race, illness, and the body. She has written for Spectator Film Journal, Fashion x Film, Cleo Film Journal, Another Gaze Feminist Film Journal, and Dilettante Army. She is an active performance artist with a background in dance and music.