Libyans sometimes refer to being arrested and taken away without warning as being “taken behind the sun.” This interview series celebrates—through conversations with formerly-incarcerated artists and their allies—the ways in which an artistic, creative life can transmute the impact and redefine the legacy of an experience within the Prison Industrial Complex.

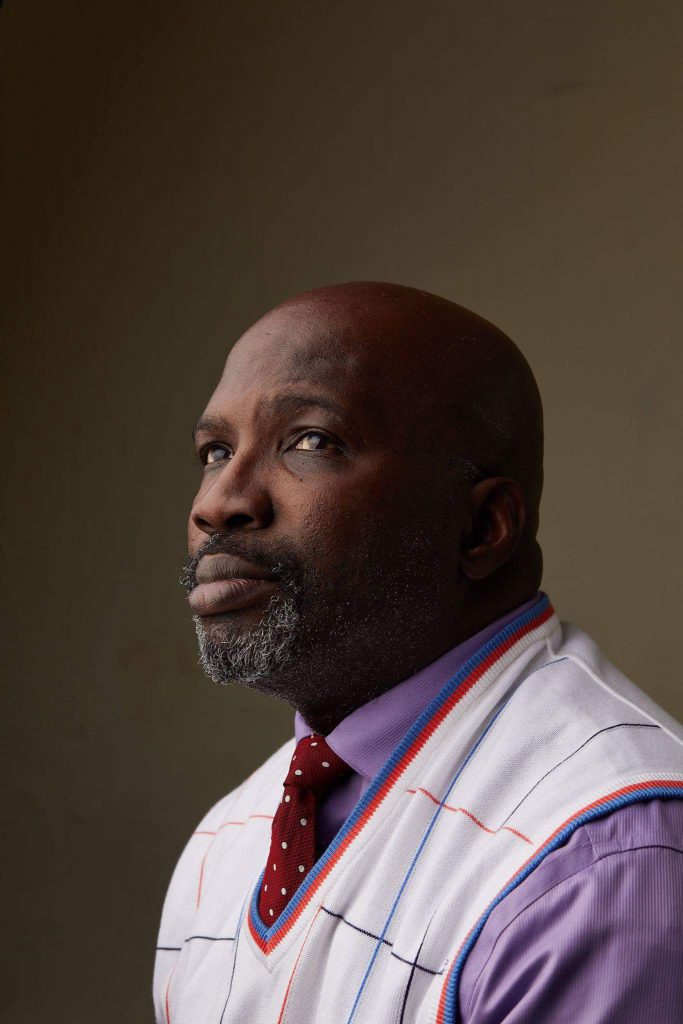

My inaugural installment took me to Kusanya Cafe in Englewood to meet up with award-winning author, poet, actor, and spoken word artist James Gordon. Everyone I met in prison claimed to be writing a book. During his time at FCI Ashland, James actually did—and he hasn’t slowed down since. We sat down for a discussion of how the South Side’s fate is like an episode of The Boondocks, the strain prison places on family ties, and the necessity of keeping an eye on the cops.

Michael Fischer: We met at The Moth StorySlam recently, where we both spoke about being locked up. We managed the first dead-even tie for the top spot that the producers had ever seen. When you saw that we had tied for first, what did that say to you about the place and importance of stories like ours—in the arts, the spoken word community, and the community in general?

James Gordon: Well I didn’t look at us as ex-cons. I looked at it as we had stories that were unique to our own experiences. The stories we told came perfectly up under [the evening’s theme of] Busted.

A lot of us are ashamed to tell our stories, but these things are just like anybody else—like someone falling off a motorcycle. You make mistakes. You make errors, and you go forward. I think that’s more important: the fact that we got on the stage respectively and were able to convey these things and be successful. And create history, because that won’t be replicated. They’ll make sure that there won’t be an actual tie again. I actually thought I had finished second, because that night it wasn’t… I don’t know, sometimes I get in a zone and I can’t hear the audience. So I didn’t know how they took my story, I couldn’t hear. But it went over well so that was real cool.

MF: You were South Side born and raised.

JG: South Side all day.

MF: You’ve said that a lot of the problems Chicago has right now are part of a well-organized force that wants to push people of color out of the South Side—to free up some of the last prime, undeveloped real estate left in the city. What do you think the future holds for the South Side, and how do you feel about that future?

JG: The South Side—if there’s no pushback by people of color or people who live on the South Side and like it the way it is—the South Side will be Andersonville or Wicker Park. And a lot of people of color will be pushed out to the less affluent suburbs, like Harvey and Dolton.

If you look at some of the things going on: they’re building I think it’s a $94 million extension of the Dan Ryan. You don’t do that in an area that’s crime-ridden, you don’t do that unless you have an agenda. You don’t do certain things unless there’s an agenda to it, and there has to be. People just don’t want to admit it. This is straight out of a Boondocks episode.

When did it become nouveau or a trend to speak about how many people are shot every day? About how many people are killed every weekend? It’s like a spotlight, it’s almost up there with Sportscenter stats. It’s like wait a minute, I don’t remember that. I’m a lifelong Chicagoan and I don’t remember them doing that. I mean yeah you always had news, but I don’t remember that.

It’s a fear factor. They want you to be afraid, they want people to say, “Oh, I need to leave Chicago. I need to get up out of here.” And then people come right on in and they raise everything up. First they lower the property values, only to have people come in who can raise it back up.

MF: When you see a person of color pulled over by the cops, you pull over also and take out your cell phone. When I learned that, it reminded me of how the Panthers out in Oakland and elsewhere used to trail police cars, to let the community know there were people out there bearing witness for them and not just against them. Talk me through your thought process in doing that. Do you see what you’re doing as a part of that larger tradition?

JG: I never thought that far into it. My brother told me about how when he was in Kentucky—Louisville, specifically—they do that. When a car is pulled over, two or three cars pull over. That’s just anybody. So with the rash of people of melanin being murdered by the police—murdered, not accident, not shot, but murdered—a traffic stop can turn into something else.

The worst thing you can do is look away from something or not say anything and not do anything. That’s the worst thing in the world you can do. So if you see something, you say, “Okay, let me pull over here in a safe spot so I can take a look.” And hopefully it’s nothing. Hopefully it’s like, “Oh, okay, they let him go.” But if it’s something, I’m right here. And if I can’t for some reason intercede physically I can at least say, “Hey, I got this footage right here, this is what happened.” I can forward it, any number of things can happen.

You got to do something. That’s the way bullying works, when people don’t stand up—and cops are bullies. I’m not ashamed to say that: cops are bullies. And we got to stop being bullied.

MF: I know you feel that your outspokenness and honesty about the racial turmoil in our country and our city has cost you some bookings and hurt your career. Along with being a poet and a storyteller, you’re also an author and actor—with your eyes on commercial success. How do you balance the moral imperative to speak your mind with the practical reality that doing so could damage your professional life?

JG: You got to fight evil, man. And I know that may sound funny because I’ve committed crimes. I’ve stolen, I have no issues with saying that. But you’ve got to combat evil, you have to. You’ve got to speak out. Everything is going to be alright, you know? My house is going to be over my head, bills are going to get paid, everything’s going to be fine. But you’ve got to speak out.

I got into it with a guy who was once a figurehead in storytelling and it cost me. They didn’t book me on shows or let me be a part of certain things, and that still continues to this day. But you know, you just keep going. Because right has got to be right. There’s a saying: “If you are conscious and a person of color in the United States, more than likely you’re angry.” So that’s all this is an expression of, and you’ve got to express that anger. I’m not an angry dude, I’m not volatile or nothing like that, but I see what’s going on and I know what it is so yeah, that’s very true. But I don’t care. It’s going to be alright, I don’t care. You’ve got to speak out.

MF: You did your time in the federal system, which meant being transferred as far from Chicago as the Federal Bureau of Prisons felt like sending you—in your case, Kentucky. I was in the state system, but I was nowhere near home either. There’s something truly sinister about the prison system—especially the Feds—going out of its way to scatter people across the country, to places family can’t easily reach. Talk about that deliberate, systematic fracturing of community, especially black community, as you’ve seen it play out.

JG: That’s a great question. I had a co-defendant who was a witness against me, so he went in first and cut a deal. They feared for his safety, and because he went in first they gave him a choice of where to go. So he was closer to Illinois, and they didn’t want us to intersect. But yeah there was a lot of that, there were a number of us from Illinois: from Chicago, Peoria. They had different codes for where you were from, and 424 was the Chicago code. But yeah it’s funny how they did that, and I had a white-collar crime so it wasn’t a violent crime.

I went to a camp first, but I got caught with a cell phone so I got moved over to low-security. It’s wild, it makes it more difficult. Not that being incarcerated isn’t already difficult, but it’s extremely difficult on the mind. People don’t understand that. People don’t empathize. Yeah you did something to get there, but the mindfuck is—man. The repetition, it’s day after day, and unless you do something… I worked in the library. I learned to type faster, I enhanced by computer skills, I wrote my book inside, I wrote poems for other guys, I worked out. I did everything I could to break up my day, so that there was always something I was doing. I left early in the morning and by the time I came back at night I wasn’t in the bunk too long. I mean sometimes I took a nap, sure, but I kept it different, I kept it varied so my mind wouldn’t get into this lull.

I had three visits, I think. I think I had three visits. Yeah, something like that. Two or three—over 16 months. Then I was moved to a halfway house, and the halfway house was in Janesville, Wisconsin. I’m from Chicago; there’s a halfway house right downtown. Matter of fact, there was one operating not two blocks from my house. Once again I’m a nonviolent offender, but they sent me wherever they wanted. So that was a different experience too, I was still like three hours away. It’s something to cope with. I think some of it may be along their guidelines and some of it may be intentional, just to fuck with you a little bit.

MF: Given how prolific you are, relatively little of your work deals directly with your incarceration. You have a very strong social and political consciousness, so I’m surprised by that. To what degree do you feel your experience with the Prison Industrial Complex influences your work?

JG: Another great question. One of the reasons I don’t speak about it that much… When I first came out, I did. It was a part of everything. But I’m a romantic. I believe in love, sensuality, stuff like that, keeping a smile on my face. One of the things I did behind the fence was I kept a smile on my face, man—as much as I could. So I like to write like that.

I’d rather speak and do stuff. I help out at the Safer Foundation, I’ve taught GED, I’ve helped other ex-offenders get jobs. I do that stuff, on the low. I write, pen pal and stuff like that. So I’d rather do that then put it into the work and the poetry. I’m a product of Cyrano de Bergerac I believe, so it’s always been romance for me.

If I hadn’t been behind the fence, I would never be this person I am now. Before I went in I was an extreme womanizer, I was a drunk. I drank a lot. I was a partier—oh my god. I believe in God, and I won’t get too preachy but I do believe that was his way of saying, “I need to curb you from this. Because if I don’t curb you from this, you’ll keep thinking that it’s alright. So you need to know this isn’t alright.” And as you know, being incarcerated, if you’ve got family it’s a burden on them too. It messes with them too, especially if you’re tight knit like my family is. So it’s like, “Oh my god.” It makes you think about things.

This person I am now is because of that: focused, aggressive, ambitious. I have to give everything my best, I have to do certain things. I owe people. I owe my mom, who didn’t like to write letters but she sent clips about Chicago because I love my city. I owe my brother, who when he had a little money would put money on my books and write to me, took my calls. I owe Elwood Pegram, my friend who got out before me and was murdered. He said, “Man, make sure you write. Make sure you write your book, make sure you get out here and do this. Make sure. Promise me.” I owe them. So I got to go.

I never thought I’d be on TV or nothing like that, man. Forget the incarceration, I never thought I’d be on TV and here I am: movies. Here I am: books and winning awards. I never thought that. So I owe them. Everything in life shapes us, but that right there? That span of time made me come out and go get it. I have to go get it every day.

MF: You mentioned how the cops are bullies. You’ve spoken about your experience being bullied as a kid and you spent years as a middle school teacher, so you’ve seen the issue of bullying play out from both sides. What are your thoughts on bullying, in all the forms it takes in modern life?

JG: One of the things that people don’t understand about bullying is there are more of us who are bullied than there are bullies. People have to realize that and say, “Hey, this is one guy.” Like the one guy who bullied me was this guy Eric. Well once I beat Eric up, then people realized he wasn’t this monster anymore. He was just a person, he was a boy—a rotten boy. Bullies work on fear, so you’ve got to combat the fear.

People never believe me when I tell them I was bullied. They look at me now: my stature, my demeanor. I say, “Well, that was decades ago. I wasn’t this guy decades ago, I was a whole different guy.” I just wanted to go to class and write girls and drink chocolate milk. But it’s important because bullying will exist as long as fear exists.

They’ve got to stop telling kids this nonsense about, “Oh, tell the teacher.” The teacher isn’t going to do anything. Don’t tell them to tell the teacher, you’ve got to deal with the bully. Most bullies, once you confront them, stand against them, they’re going to back off. It’s the only way to combat that. That’s the way it worked for me. You’ve got to start using different tactics and you’ve got to believe students when they say, “Hey, I’ve got a problem.” You’ve got to address that problem. You’ve got to believe your children, as parents. “I’m being bullied, I’m dealing with this.” Don’t just say, “Oh well, do the best you can.” No, the hell with that. Go do something. Whatever you think you need to do to make sure your child feels safe, reassure them. Do something. Otherwise it’ll continue. Because nobody likes to be afraid, that’s no good.

MF: Is there anything else you want to touch on or put out there as we wrap up, anything else you want to say?

JG: I love my city. It’s the greatest city in the world. I’ve been other places, but this is the greatest city in the world.

I love people. I grew up Lutheran, so I knew people who weren’t black when I was growing up—unlike most people, who get shellshocked. Before I went to college, before I even went to high school I knew people who weren’t black. So I don’t want anybody to ever think that I’m anti. I’m anti-evil. I’m anti-wrong. I’m for people of melanin, I’m a melanin superhero. I’m just going to give you the best I got. Stay positive and stay safe out there. That’s all.

James hosts Poetry’s Love Letter—an open mic poetry, storytelling, comedy, and music event—at Let Them Eat Chocolate (5306 N. Damen) every second Friday of the month at 7pm.

Featured Image: James Gordon. Image courtesy of the artist.

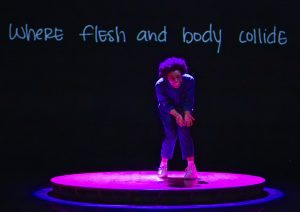

Michael Fischer was released from prison in 2015. He’s a Moth Chicago StorySlam winner, a Luminarts Cultural Foundation Fellow, and a mentor for incarcerated authors through the Pen City Writers program. His work appears in Salon, The Sun, Orion, Guernica, The Rumpus, and elsewhere, and his audio essays have been broadcast on CBC Radio’s Love Me and The New York Times’s Modern Love: The Podcast.

Michael Fischer was released from prison in 2015. He’s a Moth Chicago StorySlam winner, a Luminarts Cultural Foundation Fellow, and a mentor for incarcerated authors through the Pen City Writers program. His work appears in Salon, The Sun, Orion, Guernica, The Rumpus, and elsewhere, and his audio essays have been broadcast on CBC Radio’s Love Me and The New York Times’s Modern Love: The Podcast.