Libyans sometimes refer to being arrested and taken away without warning as being “taken behind the sun.” This interview series celebrates — through conversations with currently and formerly incarcerated artists — the ways in which an artistic, creative life can transmute the impact and redefine the legacy of an experience within the Prison Industrial Complex.

Destine Phillips is a Chicago native, activist, and entrepreneur. First incarcerated at the age of 14, Destine is now co-founder and co-director of the Rising. Elevating. And. Leading. (R.E.A.L.) Youth Initiative, which had its public launch event in August 2022. We sat down to talk about Destine’s six years of involvement with Free Write Arts and Literacy, the role art can play in transforming the conditions that lead to violence, and the most valuable things she’s learned from her creative journey.

Michael Fischer: You’ve talked about how, when you were locked up, one of the things you needed most was a genuine acceptance of your true self. What does that true acceptance look like for you, artistically and otherwise, and how did you achieve it?

Destine Phillips: True acceptance, for me, looks like… for people who don’t know me. It can be hard going into a facility that I never knew existed, with people and rules and different things going on. It’s a whole different world to me. Being in that space and people not knowing me for me, but knowing me for maybe the crime that was committed, or what they’ve seen on TV, or by word of mouth, was a challenge for me.

What that looks like for me is just being myself and allowing people to get a feel for me for themselves — to get to know me and not just judge me or put a label on me because of what they heard. Artistically, that looks like allowing me to express myself in a free space. I achieved that by going to different programs that were set up, writing in my journal every day — well, not every day, but often. Also, I was very fortunate to see my family often. I saw my family four or five times throughout the week. I even made up programs just to see my family, to get through that time.

MF: Speaking of those programs: you took part in Free Write programming while inside, and you ended up working with them after you came home. I imagine the folks who made up Free Write were a significant influence in your life, especially your creative life. When the organization imploded and then dissolved, essentially overnight, you lost not only your job but also a really important creative home. Can you talk about what that experience was like for you?

DP: I joined Free Write when I was 14, so a couple months after I was first there at the facility. It changed my life drastically. When I went there, I was able to express myself in a way that I wanted to. There wasn’t any “no, you can’t do this” or “you can’t write this”; it was free. It was a free space for me to write, to draw, to color, listen to music. That was a big outlet for me.

Also, the people that worked there were understanding and comforting and always asking, “Hey, how can I support this piece?” or “What can we add to this piece?” and encouraging it. Because I would start different projects and not finish them, because of the time limit that they gave us to be in the space. And when I went back the next time, I was like, “I want to work on something else,” and I was always encouraged to finish the piece that I’d started because it was so powerful.

You mentioned me joining after I left; I did join afterwards and it was different. Being from inside and moving to the outside programming, it gave me a lot of responsibility. I say responsibility because I was given a different role. I wasn’t a community navigator coming in; I was given the role of program coordinator. That allowed me to be on team meetings, collect timesheets, to run workshops, to run weekly meetings with the community navigators and things of that such, which also prepared me for the next phase of life that I’m in now, the next chapter.

MF: When I moved to Chicago, I was six months off parole and I remember Free Write was one of the first programs that I found out about — this was like 2016. I remember going to an event and meeting a couple of the people and I was like, “This is so cool!” That was my dream job. I was always tracking them over the years. So I remember when that all happened — when it went from “Free Write exists” and within like a week, Free Write just didn’t exist anymore, I was like “This is crazy!” This thing just evaporated overnight.

As something that you’d really become attached to, since you were 14 years old, what was it like to have it one day — and wake up the next day and nobody’s home all of a sudden?

DP: When I joined I was 14, but when it ended I believe I was 20, so I was there for a while. When it ended it was a shock to me, because I wasn’t informed about everything that was going on, so it was a shock to me too, like “Wow, we were just doing this work and now it’s ending all of a sudden.” It was a big shock to me also, but, like I said, it also prepared me for the chapter of my life that I’m in now. I’m not glad that it dissolved, but it prepared me for where I’m at today.

MF: Along with Denzel Burke, you founded the R.E.A.L Youth Initiative in August 2021. As you’re building R.E.A.L., I imagine there are ideas you’re interested in borrowing from the kind of programming you’ve been involved with in the past — and then I’m sure there are other things you’ve seen in the space that you want to reimagine completely. Can you talk about a couple examples of each: things that you’ve seen in programming that you’ve felt you should try to capture or things that you’ve seen that you think, “We should do something different”?

DP: Some of the things that I really want to capture — I wouldn’t even say capture from other organizations but just working with different organizations — is things that I would completely be like, “Yes, I want to reimagine that in a different way,” because our program is directed only towards youth and led by youth; it’s a little bit different.

The number one thing for me has always been transparency, not only with my team but also with the people who are working with us. Being transparent at all times and allowing people in the space — giving them the capacity in which they want to freely be themselves and express themselves, and holding whatever those issues are or whatever they bring to the table dear, because I understand working with different organizations.

Coming from incarceration, sometimes it’s traumatizing. I have to keep that in mind while also dealing with the people I’m dealing with, and also keeping whatever they say in the space or to me personally confidential, unless it’s interrupting or not safe.

Another thing: I don’t want to be the face of the organization. I want the people who we’ll be working with — the youth, the young people — to represent R.E.A.L. When you go on the website or when someone mentions R.E.A.L., I don’t want someone to be like, “Oh yeah, that’s Destine and Denzel or Tommy.” I want it to fully be “this program helped such and such,” and I want them to explain it in that way, so I never want to be the face of it.

MF: What are some of the most valuable lessons and experiences you’ve had working with young people on their music, art, and poetry? This is something that you’ve been doing in a lot of different contexts for years now.

DP: One of the most valuable lessons I learned, I learned recently. I work with a very talented young lady who does art — and you wouldn’t really know because she’s shy and she downplays it, but she’s really, really good. She told me one time — we were having a workshop and she expressed, “I wish people didn’t look at me and just be like, ‘that’s the girl that does art’ or ‘that’s the girl who draws.’”

It made me look at artists and it made me take a step back, like, “Okay, they might be an artist and they might do poetry or do music, but that doesn’t mean they love it or want to be seen as such.” That’s one valuable lesson I learned: to give people that space. If they’re artists and they’re good at it, it’s hard not to be like, every time you see that person, “Can you do this art, can you do this art piece or can you draw this for me?” So just to be mindful that some people are artists but that don’t mean they love it.

MF: Is there anything you’ve picked up for your own creative life — something you incorporated into your own artistic practice after you saw it in a student?

DP: Yes and no. I’m not a full-time artist, but when I do have the time to do it, I do think about different art pieces that I’ve seen or people that I’ve come across based off the assignment that was given. Because normally it’s an assignment that led to the art pieces that I do. I’m mindful of that, but also thinking about other work that I’ve seen that inspired me or spoke to me in a way, and I just express it — how it fits in my life.

MF: That’s interesting, that you feel comfortable working off of assignments and prompts like that, because sometimes creative people get really cagey about that. They’re like, “No, you’re confining me, I don’t want rules!” So that’s really cool.

You were recently featured in a Teen Vogue article about alternatives to prison and police. You said, “I wish people would ask why violence happens and center their response on transforming the conditions that lead to violence.” What role does artistic and creative capital have to play in transforming those conditions? A lot of the activism you do is around systemic ways that we can change those things, but what role does art have to play in that process?

DP: There’s a big role that art plays in it, because art is not just a picture — it’s life. Everything around you is made up of some form of art. I feel like the environment you’re in is made up of art. So if that environment is tainted, or what you’re used to is not beautiful to you… you can’t heal in the same environment where you got sick; you need a new environment. You need an environment that maybe has different colors and different abstracts and different ways of doing things than what you’re used to doing. An example would be more youth centers around us, accessible to young people when they go out into their communities.

MF: You know how when you go into a lot of prisons and jails and they’ve let someone paint an eagle on the wall or something? When you’re talking about how you can’t get better in the same place you got sick, I’m curious: when you see stuff like that — and I imagine they have a lot of that in the youth facilities — do you feel like that kind of thing is valuable, or do you feel like in those environments it’s like putting lipstick on a pig?

DP: I feel like, in a way it’s almost like, “Hey, you’re in this environment that’s going to torture you, but at least you got a pink wall or at least you got colors to look at while you’re in this environment.” For most people it can help, for some days. When people are dealing with depression and they just don’t want to be bothered, I guess looking at colors sometimes can make you happier or think about other things, instead of just looking at a black wall or one solid color, especially if it’s a dark color. But yeah, definitely.

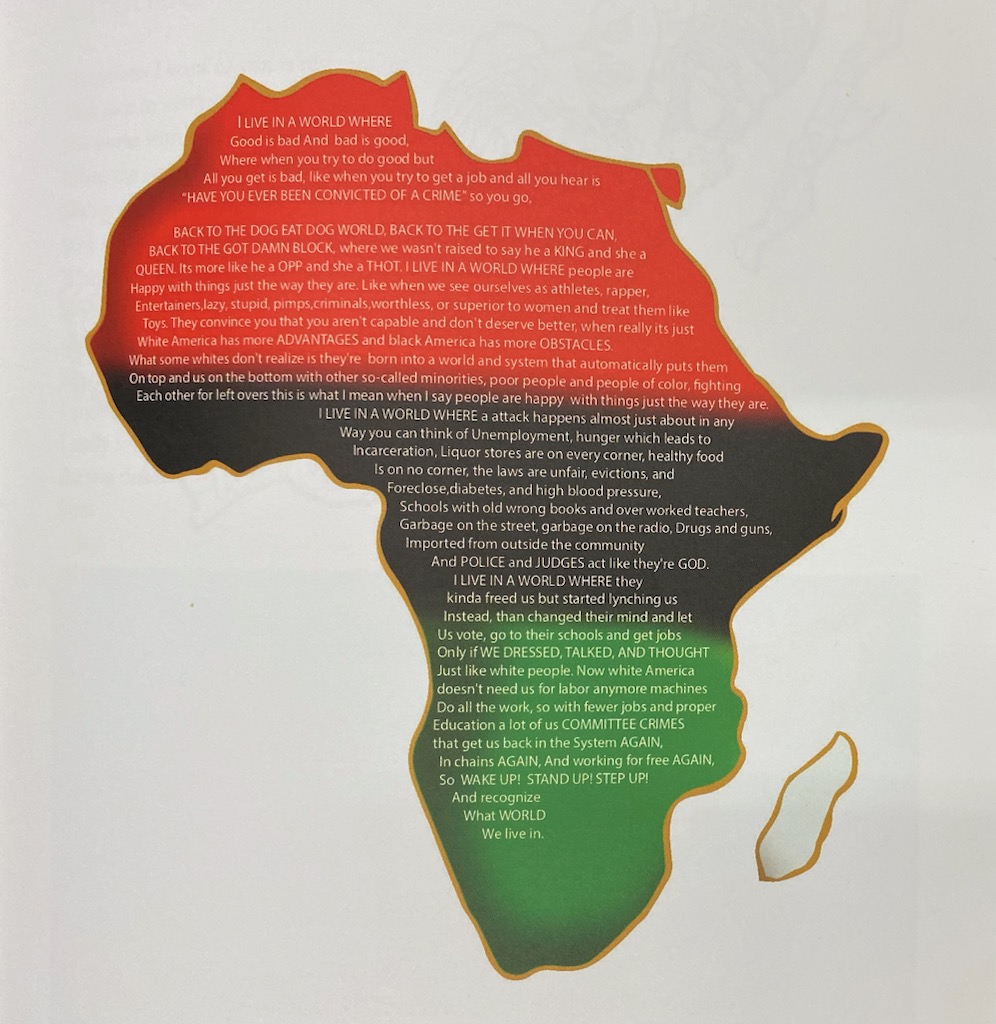

MF: In 2016, your work was part of an anthology of creative writing and artwork. Can you talk about the experience of putting all that work together and what it was like to see your work in print, out in the world?

DP: I’ll go back to when I mentioned doing those workshops. I was always directed to finish a piece before I went to the next piece, and that was probably because of the end goal. I had numerous pieces, and I didn’t know the anthology was going to be a thing until they had all my artwork and they were like, “Which are your top favorite?” And I was like, “Uh, it’s kinda hard.”

In the beginning, in doing the different pieces, I didn’t know it was going to be published, until like a month or two beforehand. It took some time to get published, because of different rules and different stipulations the facility had on what can be published and what can’t.

MF: Do you think that helped? Do you think not knowing, as you were creating, that it was going to be published — did that help you just do it for you?

DP: Yeah, just freely do it. I feel like that was a big thing as well. I liked the fact that they had us working towards something. They probably didn’t know it was going to be an anthology or that they were going to publish it either, but they had a lot of great pieces and it was an idea, so why not?

Working towards it, when I found out, I was like, “Okay, can I change this? Can I make this this color?” I was really excited about it, but I also was glad that they didn’t tell us in the beginning, because I probably would have been like, “Okay, who’s gonna be looking at this?”

MF: What’s it been like to share with folks on the outside — family and friends — now that it’s in print?

DP: It feels good actually, but it also… when I read over it now, I can see the change in my artwork and in my mindset. It’s a huge change. Just by reading it or looking at it, you can tell — well, I don’t know if you can or not, but I can tell I was in a different space than where I’m at now.

Now I’m free; I’m relaxed. I’m thinking about other stuff that’s not related to me being depressed or wanting to go home. Because when you’re in that type of environment, that’s all you want to write about is going home, or you want to write about memories.

MF: So you feel it’s a wider lens you’re using now, since you’re not so fixated on “home, home, home”? Now that you are home, you can see more widely? That makes sense.

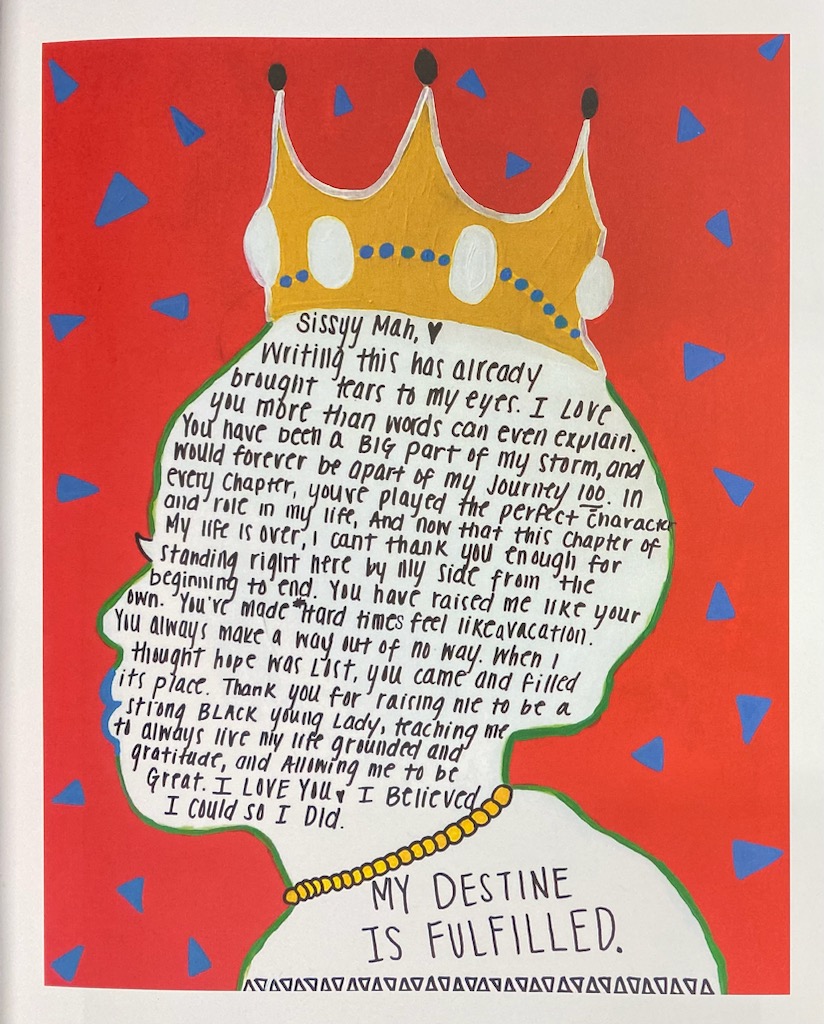

Before we started recording you were showing me the silhouette piece, and now that we’re on tape I was hoping you could retell that story about how that piece came about.

DP: The silhouette I created is a silhouette of myself from my shoulders above. I created that piece in 2018; it was about six months before I was being transferred to IDJJ [Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice]. I created the piece just to represent myself and how I felt. It’s a silhouette of me and I got beads around my neck with a crown on my head, and then beads around the crown. And then the background of course is in a bright color, and then triangles.

I didn’t think I was gonna give it away, because so many people was asking for it, but I did end up giving it to someone who I loved dearly while being at that facility. When I gave it to her, I was also writing letters to people who I would miss. And she asked if I can write my letter on the silhouette, instead of writing it on paper. When you all see that piece, the writing on the inside is actually to someone who actually worked there.

MF: Can you say more about what issues and themes you’ve been exploring in your creative work up to this point, and what you see as the next evolution? When you think about your creative life looking forward, what new challenges, new perspectives do you imagine taking?

DP: I’ve also worked on big art pieces. I worked on a mural when I got out, up north; that was around women’s justice and advocating for women. I also am now working on a project with Illinois Prison Project. It’s not directed towards just art, but we do have an eight-month series where we rotate in-person and virtual means. We have to choose from different resources and by the end of the eight-month series, we should have a 15-minute or 30-minute presentation, talking about and informing people on our own advocacy or philosophy around… basically dealing with how we see ourselves now and how the carceral system had an impact on us.

MF: When you think about that prompt, how are you answering that question for yourself?

DP: Based on the resources they’ve given us, it’s basically people that have done this in the past, we’re using their 15 or 30 minute things as resources to contribute to our own. I haven’t read anyone’s yet, but I’m thinking about the most valuable people to me, different events that took place that changed me — not changed me, but evolved me — into who I am today, different events or things I went through to get to where I’m at now.

MF: Is there anything else that you wanted to talk about that we didn’t get to, anything you want to plug in terms of what’s next for R.E.A.L. or anything else that you’re doing?

DP: I want to announce we did just have our public launch for the program a couple of weeks ago. If you are about building revolutionary consciousness, working with the youth, and being involved in a movement, please feel free to reach out to us via our website and please follow us on all social media platforms. We’ll respond back. And shoutout to my team; I love them.

Learn more about R.E.A.L. at realyouthinitiative.com. Follow them on Instagram @realyouthinitiative and on Twitter @weareREALyouth.

About the Author: Michael Fischer was released from prison in 2015 and is currently a humanities instructor in the Odyssey Project, a free college credit program for income-eligible adults. He’s an Illinois Humanities Envisioning Justice commissioned humanist, Luminarts Cultural Foundation fellow, Illinois Arts Council grantee, and a finalist for the PEN America Writing for Justice Fellowship. His nonfiction appears in The New York Times, Salon, The Sun, Lit Hub, Guernica, The Rumpus, and elsewhere, and he’s been featured on the Outside Magazine Podcast, The New York Times‘s Modern Love: The Podcast, and The Moth Radio Hour.

About the Photographer: Kristie Kahns is a photographer and art educator based in Chicago. Remaining close to her first passion of dance, she has spent over a decade as part of the Chicago dance community through her camera. She is also a dedicated teaching artist, creating analog photography programs for teens. She is currently a graduate student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, studying art education and administration.