Libyans sometimes refer to being arrested and taken away without warning as being “taken behind the sun.” This interview series celebrates — through conversations with currently and formerly incarcerated artists — the ways in which an artistic, creative life can transmute the impact and redefine the legacy of an experience within the Prison Industrial Complex.

Saidayah Kirk isn’t waiting on her release from a youth prison to launch herself as an artist. First incarcerated in 2018 at the age of sixteen, Saidayah began teaching herself how to draw and paint during the early days of the COVID pandemic. Now, with a number of arts internships, workshops, and even sales already under her belt, she’s looking ahead to the next phase of her creative life.

Saidayah received a day pass to leave the youth prison where she’s currently incarcerated in order to participate in this interview in person. We met in a former artist’s studio on the South Side of Chicago to talk about the symbolism in Saidayah’s work, her techniques for pushing herself to get better, and maintaining ownership over her talent while incarcerated.

Michael Fischer: You began taking art more seriously just a couple years ago, when the COVID outbreak started. At first, you were working mainly with colored pencils. What was your early work like? What kind of things were you drawing back then?

Saidayah Kirk: First starting out, I had little to no confidence behind my artwork, so rarely would I venture outside of my comfort zone. In the beginning, my early work was mostly sunsets and trees, things of that nature.

MF: I imagine part of that was because you’re starting from a place of confinement. The initial imagery that came to you, was it all nature-based?

SK: I had a natural pull towards nature, being that that was one of the main consistent things in my surroundings.

MF: At some point on this journey of teaching yourself how to draw and paint, you turned that talent into a business — exchanging your art for food or whatever else you needed. Were those essentially commissions you were doing for other youth? How much of an exchange business was that for you at the time?

SK: No actually, the clientele for that organization mainly consisted of correctional officers and staff throughout the facility. Although I had the opportunity, I never really worked with kids as far as business opportunities. I think it was more wondering where my art would go. Instead of doing artwork that I knew would be in the cell next to me, I was more comfortable doing artwork that I knew would be in homes, in offices, things like that.

MF: That’s interesting. Knowing that it was going to be out in the world, that was a comfort to you?

SK: Yeah, I think that was it.

MF: There’s something that sounds kind of nice about being able to check in on your work, if it was nearby. If it was someone in the facility, you’d still be able to see it around and say, “I did that.” But that didn’t appeal to you.

SK: Not at the time. I think my focus was more on getting my art out for more people to see, and I figured keeping it within the facility would kind of limit that.

MF: That makes sense. It’s certainly difficult to be self-taught in any circumstance, but to be self-taught while incarcerated as a young person takes a lot of hard work, takes a lot of talent. How have you gone about improving and growing as an artist despite the difficult conditions?

SK: Navigating myself through art, I learned the most effective way to gain new skills and better my pieces was to simply challenge myself and try new ideas. Whenever I came up with something new, I would channel it and just see where that path would lead me.

MF: What does that look like? Without someone leading you and doing it all off the top of your head, how did you know how to challenge yourself or what to do to get better?

SK: For example, when I would draw faces, my go-to would be only one position. So I would try something new, maybe draw from an angle or something like that. It was a lot of hard work, but the more that I would do it, the more it would look better.

MF: So maybe if you’ve only been drawing face-on, you’d do a profile, or maybe angled slightly to the side, and that would help you expand what you were able to do?

SK: Yeah, a lot of trying different things, different angles.

MF: You made a piece for an auction at the National Association of Community and Restorative Justice Conference, and it ended up receiving the highest bid of all the art that was up for auction. What was it like to hear that had happened? You talked about wanting to get your art out into the world, and then it gets out in the world at this conference and people bid it up more than any other piece of artwork there. What was that like to see people show so much tangible interest in your work and really put their money where their mouth is?

SK: I was ecstatic; it moved me tremendously. I was able to attend the event, so seeing crowds of people surround my painting to take pictures with it and admire it left me in awe. Altogether it was just a great experience.

MF: While you’ve been locked up you’ve also done an internship with SkyART, you’ve participated in Monica Trinidad’s Making Art for the People Workshop, and you were recently part of the inaugural cohort of the Grassroots Collaborative’s Chicago Creatives for Justice Fellowship. What were your favorite parts of those experiences? What were some of the most valuable things you took out of that programming?

SK: One of my favorite parts of it all was simply being in an environment with other artists, even artists with more experience than myself: meeting them, learning about them and their process of art-making. One of the most valuable things that I’ve learned was that a lot of the participating artists worked with digital art, and if I wasn’t the only person in the room then I was one of few who worked with raw materials. There was something about that that really stuck with me.

MF: Can you give an example of someone you learned a lot from and something specific that you were able to take away from what they’d been doing?

SK: There were a lot of artists in the room that would inspire me, just off of the fact that there were so many different techniques and things like that. One woman I remember, I met her a few times, I think she participated in all three of the other organizations. Seeing the many different things that she could do on so many different aspects and levels, that pushed me harder to critique my work in a way.

MF: Seeing someone with that level of versatility and then seeing that so many people were involved in digital media and new media… obviously new media is probably not an option for you at the prison, but is new media and getting into more digital work something that you’re interested in for the future?

SK: Definitely. By seeing everyone else work with digital arts and things like that, it opened a new door for me, a new feel. There are so many things that you can do with digital art that I wasn’t aware of until the programs.

MF: What kind of stuff excites you about it?

SK: I feel as if it gives it more of a clean look, a little bit more professional.

MF: Have you been able to stay in touch with some of the folks that you met in those workshops? Obviously not hanging out with them, but have you been able to stay in touch over email or with letters? Have you made social connections above and beyond the art that you’re going to try to foster when you’re able to spend time with those people directly?

SK: There’ve been a few individuals that I’ve met where we’ve maintained direct contact. But because of my circumstances, we can’t be so close and involved with just anyone. A lot of times my mentors take my business cards to people I come across; they’re like the middle man between us, most of the time.

MF: Who are your influences and inspirations as an artist? These don’t have to be other artists, these can be musicians or whatever helps you get your creative juices flowing.

SK: As much as I wish that I had a bunch of creative people and artists that really motivated me and pushed me, for me it would be my counselor. It was her that played an enormous role with pushing me to get my creative flow really going. She brought different ideas from Instagram artists. She was also big on [designer Virgil Abloh], so she would come in with pictures from [fashion label] Off-White and things like that, and it would just inspire me and give me more ideas to work with.

MF: So she would go and find stuff and bring it in that she thought you would be into?

SK: Yeah. There was this one artist and my counselor used to always purchase coffee mugs with her artwork on it — things like that. I just thought it was really cool. Of course, I envisioned my own artwork on things like that.

MF: You mentioned you don’t really have a lot of family influences in terms of artists, but you said you had maybe a couple people that had been locked up and created work and that was a lead for you.

SK: Within my family I never really had a bunch of artists, but I did have an uncle; he was incarcerated for many years. One thing he would do is create holiday cards and they would really impress me, because I didn’t know our family to be artists or drawers or anything like that. In return I would try to imitate it a little bit and make my own holiday cards. Of course at the time, they were terrible. Other than my uncle, I didn’t have many family members that influenced my art.

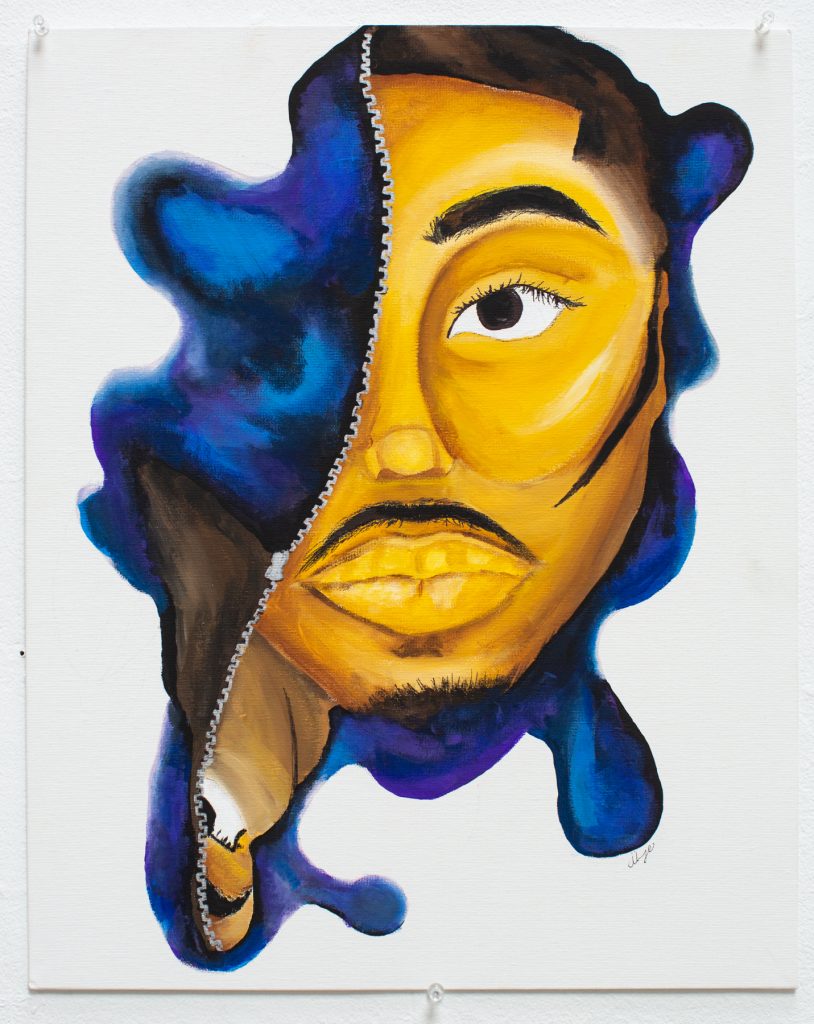

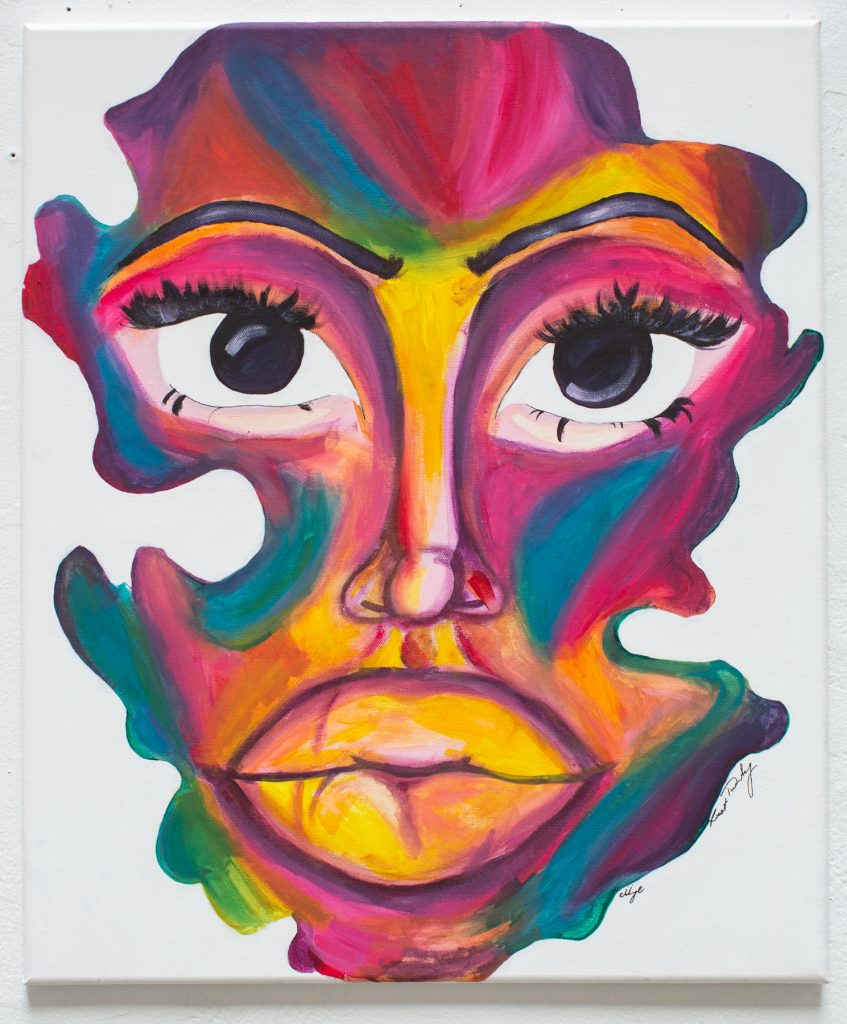

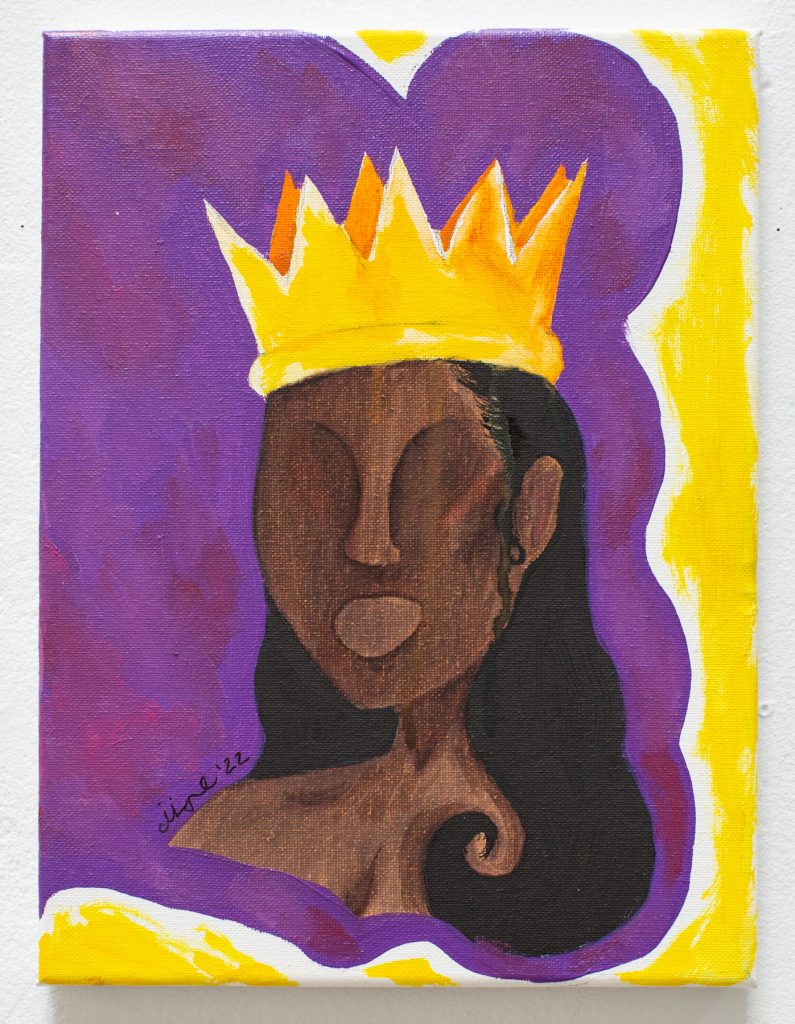

MF: In a number of your pieces that I’ve seen, the eyes a lot of times are either closed or redacted or covered or they’re missing completely. Can you talk about that symbolism and what that’s speaking to, in these eyeless or eyes closed or eyes redacted portraits?

SK: When creating, I feel as if giving or including eyes or leaving them intact personalizes the canvas. If I include eyes and leave them clear to vision, I think my audience will feel as if they’re looking at someone. Whereas if I don’t include the eyes or cover them, then I would like to think that my audience could imagine themselves in the portrait and put themselves in it. I believe that creates an effortless emotional connection with my art. That’s what the eyes mean to me.

MF: That’s so interesting, because so many people talk about wanting it to be personal and to be specific, so that’s interesting that that’s not what you’re looking for. It’s like an empty vessel and people can fill it with themselves, identify with it and put themselves in it.

Crowns are another visual symbol that repeat across your recent work. What is it about the imagery of crowns that’s capturing your imagination at the moment?

SK: Being incarcerated as a young person can be unpleasant, and so I use a lot of mantras and inspirational quotes to keep a healthy, positive, and powerful mindset. I felt like crowns would be the best way to represent that — showing that no matter the predicament or even the inevitable, sometimes cruel, routines that prisons have to offer, my value as a person will not and has not been decreased.

MF: So the crown symbolizes the inner worth that remains throughout all of that. Oh, here’s what I was going to also mention about the eyes: when I saw it, it seemed to speak so powerfully to the carceral state in general. There’s so much of that in legal documents — they redact stuff, you see court transcripts and they’ve blacked stuff out. In the pieces I’ve seen where you do the black redaction over the eyes, as people do in court documents, it seemed to speak very powerfully of the system itself. Does that have any resonance for you?

SK: While making the art, it was mainly leaving a blank space for people to fill in. Afterwards, I started to realize things like that. For myself with my case, there were a lot of things that were swept under the rug and not really looked at, so I felt like it was me against the world. Leaving the eyes out takes emotion out of the picture.

MF: I don’t know if you felt this way about your situation, but so often it feels like what’s left out is the most important stuff — the stuff that’s like, “If people only knew that, then they would really get it. But if it’s not there, I’m not going to be able to get anyone to understand what my full experience was. All the things that would make me most human and get people to see me how I would want to be seen are being deliberately left out.”

SK: Exactly. I’ve heard plenty of times that the eyes are the window to the soul, so to block them out and to not include them, all people really see is the shell of that.

MF: You’ve mentioned before that at first you downplayed how good your work was and you didn’t see how great you were as an artist. You played it off as, “Oh, this is just what I’m doing to pass the time.” But these days you’ve said that you’ve come to truly believe that you have a future as an artist — which I think everyone who has seen your art agrees with. What changed for you? What allowed you to really see and accept that you were talented and that you had a future in this?

SK: It’s really hard to say, but I think the biggest part about it was just over time I learned to appreciate my creativity and my ability and the things that I’m able to do. There are people who really admire my work and things like that. Definitely also the programs and opportunities that were brought to me while being incarcerated, that’s a lot itself.

MF: You’ve spoken about the way that a lot of times, as a talented young person in a facility, people want credit for that. They want to be identified with that, like, “We taught her everything she knows.” How do you imagine pushing back against that? What does that look like for you, to take ownership of your own work and your own talent, and not let people slide in and take credit for what you’re doing?

SK: Sometimes it can be difficult. In the past, a lot of my opportunities and art things like that came from the facility itself; they would find them for me. Now with my mentors and things like that, we look for my own opportunities and they advocate for me and I advocate for myself, so that before the facility even knows about the opportunity that I want to get involved in, I’ve already put my foot in the door and told them first-person about me and how I came about.

MF: So not waiting for the things to come to you but being proactive, you go find them yourself and that puts you in the driver’s seat in that way. I also wanted to ask you: I’ve seen a couple of your pieces that use mixed media. I think it’s the hair I’m thinking of, where the hair will be made of — I don’t know if it’s yarn or what it is. Can you talk about bringing in not just colored pencils and paint but bringing in things that make the piece three-dimensional, and how you got started doing that?

SK: My counselor used to have a box of a bunch of random things. There’d be marbles in there, markers, glitter, things like that. One day I was just in her office and I was trying to come up with different things. She let me take the box back, and while I was in my room I had a canvas I was working on but didn’t really know which direction to go in with it. So it was just sitting for a while. And I started to use yarn and stuff as the hair for texture and things like that, and I remember bringing it to my counselor and showing her that this was something I wanted to get more experience on. She helped me with that a little bit more, but it was really just trial and error.

MF: We’ve talked about your process and how you really haven’t been working that long, and you’ve already grown so much as an artist in such a short period of time. What do you think is the next step in your creative life, what are your goals in your artwork? I know we talked about getting into new media, maybe digital media. What are some other goals, what do you see as your next steps as an artist?

SK: Right now, a lot of my focus has been leaning more towards more publicity and exposure. I’m currently working on a website. It’s going to serve the purpose of an online portfolio. But eventually and potentially I want to have an online store as well. As I mentioned before, I want to sell merchandise with artwork on it and things like that.

MF: Like the cups that your counselor would bring in: shirts, cups, posters?

SK: Yeah.

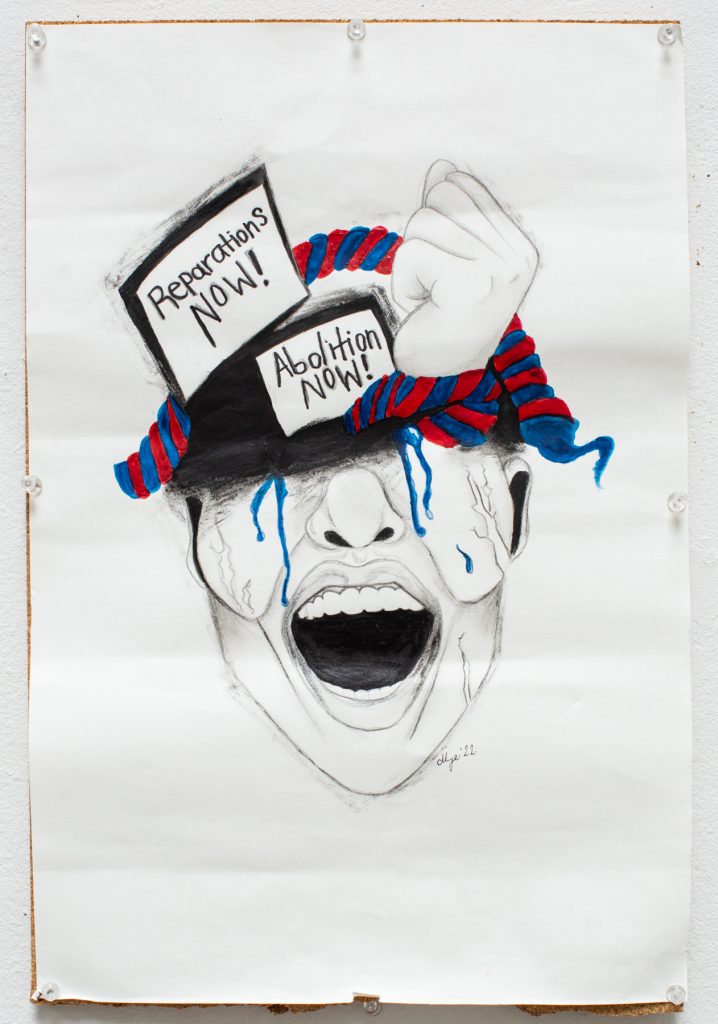

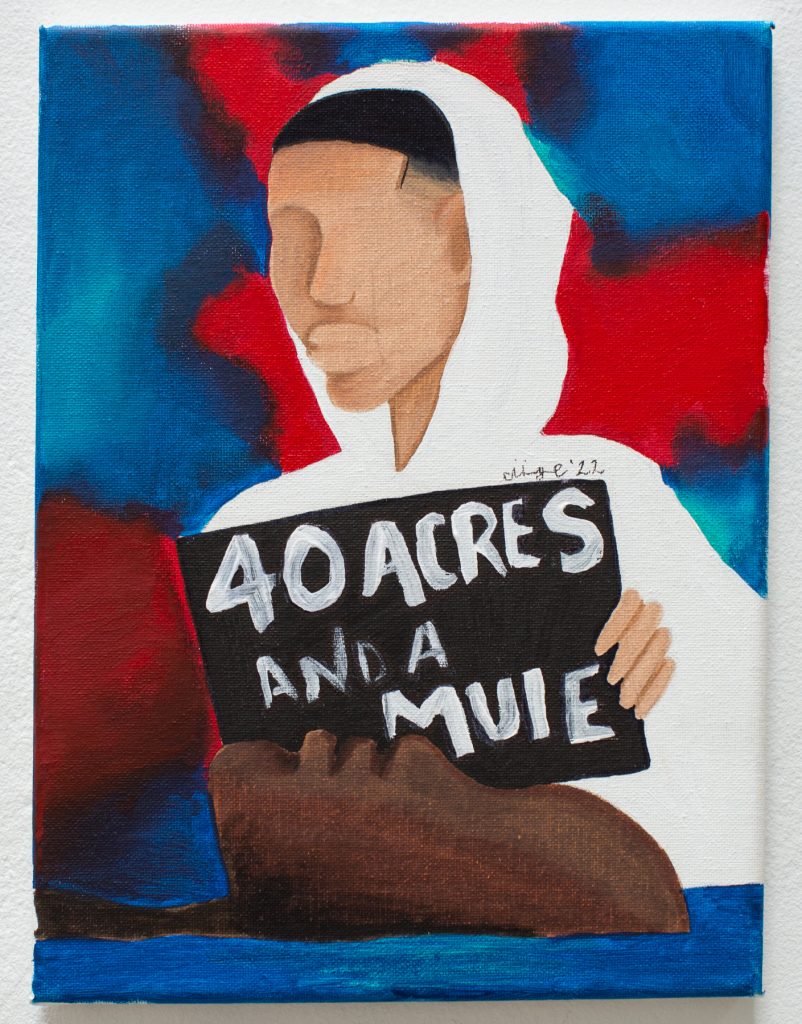

MF: A lot of artists that are incarcerated or formerly incarcerated talk about the intersection of their work with their struggle to get free, and then when they get out they continue to use their art as a platform. I think you’ve been doing a lot of this with the auction and at the conference, using your work in spaces to push for abolition, your own freedom, etc. How are you thinking about that in terms of your art — not just as a commodity that you can sell and promote but also as something that is part of helping dismantle a system and make yourself, and other people, free?

SK: In the past I’ve made a few pieces that push that motive. I haven’t made any recently, but, of course I have interest to do so. Working with Monica Trinidad, we talked about a lot of movement art, to get a lot of people involved and push them for a cause. That’s definitely something that I’ve been planning to touch more on with more artwork. I’m a person that feels that images speak more than words at times, so just to see an image will stir emotions. Making more artwork to push motives is definitely a part of my plan in the near future.

About the Author: Michael Fischer was released from prison in 2015 and is currently a humanities instructor in the Odyssey Project, a free college credit program for income-eligible adults. He’s an Illinois Humanities Envisioning Justice commissioned humanist, Luminarts Cultural Foundation fellow, Illinois Arts Council grantee, and a finalist for the PEN America Writing for Justice Fellowship. His nonfiction appears in The New York Times, Salon, The Sun, Lit Hub, Guernica, The Rumpus, and elsewhere, and he’s been featured on the Outside Magazine Podcast, The New York Times‘s Modern Love: The Podcast, and The Moth Radio Hour.

About the Photographer: Kristie Kahns is a photographer and art educator based in Chicago. Remaining close to her first passion of dance, she has spent over a decade as part of the Chicago dance community through her camera. She is also a dedicated teaching artist, creating analog photography programs for teens. She is currently a graduate student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, studying art education and administration.