Featured Image: Installation view. A brown couch sits in a white-walled living room, on the back wall hangs three framed photographs. Image courtesy of 6018North.

If you read A Raisin in the Sun in high school and were asked what the play is about, you would likely reply “the experience of a Black family moving into a white neighborhood.” While Lorraine Hansberry’s play specifically depicts the Youngers, a Black family in Chicago, RAISIN, currently on view at 6018North, uses the play’s broader themes as the basis for an ambitious exhibition featuring more than 30 local and international artists working in a wide range of media.

In a conversation about the show curator Asha Iman Veal explained that several years ago she came across archival images of productions of the play in Eastern and Central Europe from the 1960s, which led to further research. She found that soon after its Broadway debut in 1959, A Raisin in the Sun was adapted to other local contexts worldwide—by the 1960s it had been translated into 30 languages. The idea for the exhibition came from her research process. She says her approach to RAISIN mirrors what happened with the stage play—the geographic and racial scope traveled far and quickly. Her decision to present an inclusive group of artists and artworks reflects “the legacy of what the play is itself, it’s a very specific story that’s universal in uniting people.”

6018North is a house in a residential neighborhood, making its setting for an exhibition centered on the concept of home quite fitting. In my conversation with Veal she describes wanting visitors to move freely throughout the space, wandering around the home as if it were the Younger’s but “reimagining different countries, contexts, and dialogs.”

Veal organized each floor of 6018North around a specific theme. The third floor consists of installations that consider homes as sites of identity-based violence. The second floor looks at home as a place of nostalgia and fond memories. The first floor, which is the most cohesive thematically, considers home in ways that directly reference the play.

Veal makes good use of the entirety of the house, including the front yard, porch, and unique interior rooms. The front-facing fence features Gloria Talamantes’s Erasure 1 and 2, 2021, colorful murals that include the buff-brown paint the City of Chicago uses to erase graffiti. In her artist statement Talamantes notes: “This project engages ideas of perception, and what is little known other than by public artists and graffiti artists themselves about double standards of urban expressions in Chicago and around the world.” To her point, this North Side graffiti has not been targeted by the City.

Talamantes’s 93 ‘Til Series, 2021, is displayed on the second-floor landing and staircase coming up from the first floor. Her collages of photographs of buildings on a blue background further demonstrate the way brown buffed walls are manifestations of community disinvestment and segregation on the South and West Sides. In addition to the photographs, Talamantes includes chips of brown paint collected from walls across the city, illustrating how the graffiti blasters program is erasing artistic expression in majority-BIPOC neighborhoods.

Moving up the front steps, visitors are confronted with Kyle Bellucci Johanson’s untitled (“radical” hospitality and its constant gardeners) 2021, a grid-like installation of 69 doormats, each with “WELCOME” printed in black ink. The mats also have other phrases (“HARD WORKING AND HONEST,” “YOU GOTTA ADMIT,” “THOSE PEOPLE,” “THANK YOU BUT NO THANK YOU,” “I NEVER INTENDED THAT,” “I DON’T HAVE TO TELL YOU”) spelled out in grass seed.

While these sentiments have ambiguous meanings, many are taken directly from the one white character in A Raisin in the Sun who lets the Youngers know that they are not welcome in the neighborhood. Text from the play is supplemented with other micro-aggressive words and phrases often used by art institutions. Bellucci Johanson’s artist statement says the words reveal “the obscured language, rituals of hospitality, and passive-aggressive behaviors that historically and today remain as the constant gardeners of white supremacy, and as the veiled gatekeepers to resources and equity.” A metaphor for the way outsiders are politely discouraged from moving into new neighborhoods, visitors are cautioned not to step on the growing grass and must navigate an awkward path to access the home.

Entering the living room at 6018North, which is intended to reference the play’s setting in that space, visitors encounter photographs and an audio piece by Brett Swinney. These works parallel the commentary on the opportunities homeownership brings seen in A Raisin in the Sun. Bessie & Tessie, 2021, are photographs of Swinney’s grandmother and cousin, respectively. In 1965, Walt and Bessie Theus purchased a home at 342 W. 100th St. The house, shown in a photograph situated between the two women, is still owned by the Theus family. Keep the Land in the Family, 2021, is a poignant audio recording of a conversation between Caroline Theus Swinney and Walt Theus Jr., the eldest children who grew up in the home. Their reflections on their childhood and their understanding as adults about how homeownership shaped their families are reminders that such opportunities should be more widely available.

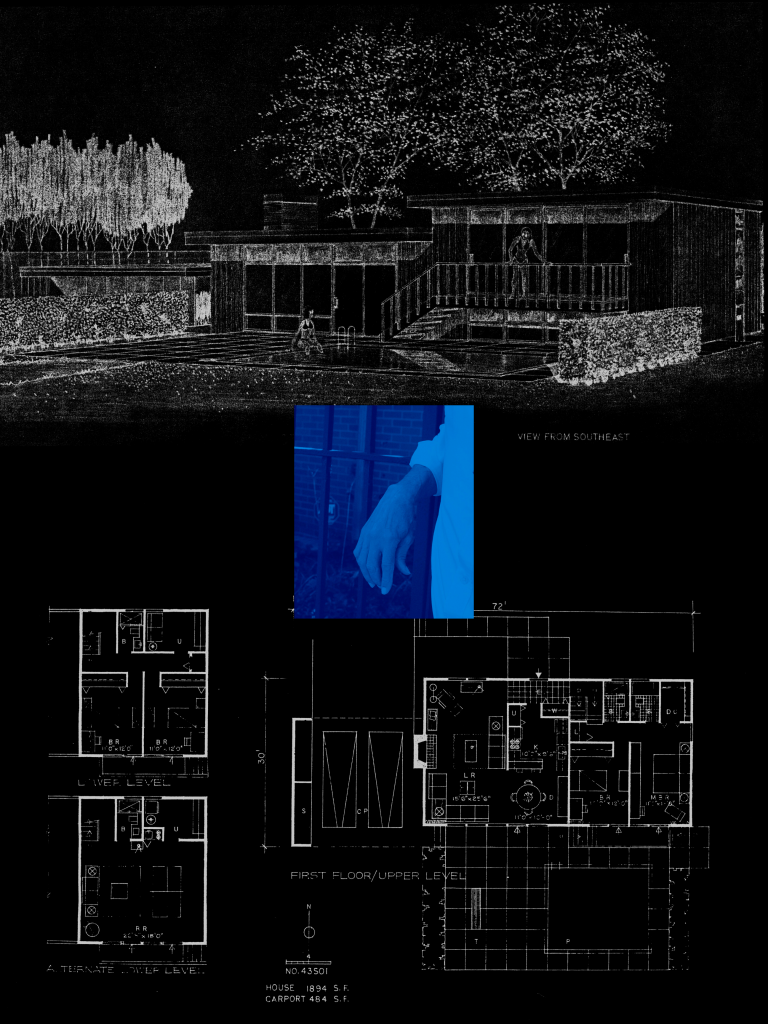

Across the hall in the dining room is zakkiyyah najeebah dumas o’neal‘s to understand what space made for us feels like…, 2021, which she says reflects on Hansberry’s depiction of Black mundane life on the South Side. A work that begins with personal referents—the artist’s adopted parents and paternal grandfather’s biographies—her images reference the Hyde Park and Kenwood neighborhoods. She uses her grandfather’s architectural designs and floor plans, created in the modern style of Mies van der Rohe, as a lens to examine socio-economic status and upward mobility. Plans for the never-built structures are contrasted with photographs of her family’s different homes, among other elements, in order to demonstrate the different classes within the African-American community and her own family.

Although continuing through the house diffuses the tighter themes of the play, overall, the artworks on view are well-crafted and have important stories to tell. The exhibition is accompanied by an ambitious and compelling suite of programs. Additionally, there is a conversation with the curator and the digital catalog which is exceptional and features artists’ statements and videos. In lieu of traditional wall labels, this information is also available through QR codes next to the artwork. Whether or not you are familiar with A Raisin in the Sun, a visit to RAISIN is well worth the effort for its thought-provoking content in an apt context.

RAISIN is on view at 6018North from September 17 – December 18, 2021.

Susan J. Musich spent twenty years as an educator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago communicating fresh perspectives to non-specialist audiences. This experience infuses her approach to writing about art. In addition to freelance writing, Musich serves as a consultant to local foundations and manages the tour program at EXPO CHICAGO.