January 22nd marked the 48th anniversary of the Roe v. Wade decision, but the debate around reproductive rights didn’t end there. Denying Title X family planning dollars to providers like Planned Parenthood and concerns over Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s appointment to the Supreme Court are just a few examples of how the fight continues. Engaging with and broadening the discussion of how fertility is politicized, Reproductive: Health, Fertility, Agency at the Museum of Contemporary Photography (MoCP) provides a comprehensive look at reproductive issues through art.

Kudos to MoCP for tackling the issue broadly, focusing on the spectrum of experiences, not just birth control and abortion. The exhibition includes artworks addressing desire and sexuality, the heteronormative childbirth industry, and menopause. That said, the curatorial narrative is strongest in articulating the ways in which patriarchal systems affect reproductive freedoms.

The largest gallery space is devoted to Laia Abril’s project On Abortion: And the Repercussions of Lack of Access, 2016. Her archive of images and text is based on years of research about the consequences of restricting access to safe and legal abortion. Extensive text panels educate us about histories which are unfamiliar and unpublicized—like the extent to which fanatics harass and target abortion providers, and tales of women whose doctors report them to the police after attempting illegal abortions. Horrific stories from at home and abroad line the walls: methods of ending unwanted pregnancies including poison, knitting needles, falling down stairs, and using a coat hanger—now a symbol of the pro-choice movement.

Abril was trained as a journalist, and while much of the installation takes a documentary approach, she includes out-of-focus portraits to accompany some of the stories. A photo of a young girl is titled Cause of Death: Parental Consent Needed, USA. And there is Michelle, an Irish woman with cancer who was unable to receive an abortion in her home country, despite the recommendations of her doctors so that she could continue her cancer treatments.

The strength and heart of the exhibition are in the individual stories and injustices suffered by so many women. The curators note that it was difficult to find work about reproductive issues in general, but particularly hard to find pieces that also address systemic racism. Betsey’s Flag, 2019, by Doreen Garner, tragically does so. One side of her flag presents what appear to be swaths of black skin serving as stripes. The other side comprises textured reds and pinks, evoking internal organs. Betsey’s Flag pays tribute to Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey—enslaved women who were subjected to horrific medical experiments by Dr. J. Marion Sims, often considered the “father of modern gynecology,” in his pursuit of a treatment for vesicovaginal fistula. The work reminds us that many medical advances, including the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, have been built on Black lives, a dichotomy made clear in the title’s reference to Betsey and Betsy Ross.

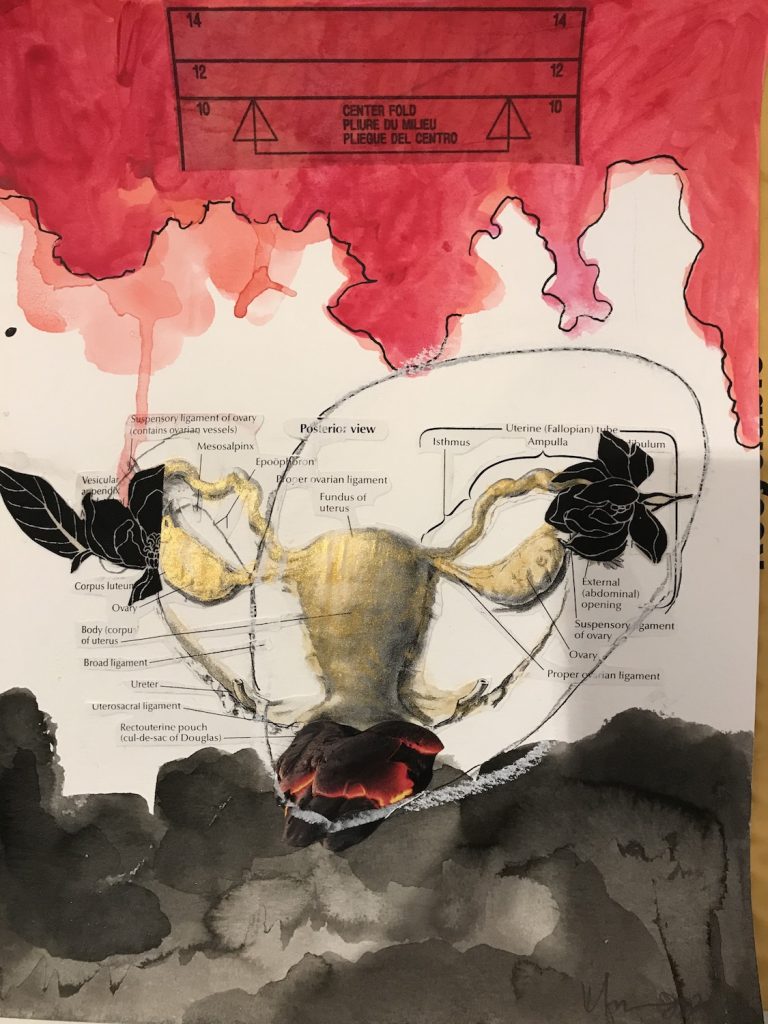

Individual struggle becomes autobiographical in Krista Franklin’s Under the Knife book project, 2018, which uses text, image, documents, and collage to chronicle her battle with uterine fibroids, a condition that can cause infertility (another marker of reproductive health) and disproportionally affects Black women. Franklin suffered strangers asking her if she was pregnant because of her distended abdomen as well as years of dismissive responses from medical professionals. In correspondence with the curators, Franklin describes the book as a “speculative exercise (speculative, speculation, speculum . . . ) about the long-term effects of systemic racism and misogyny on families, and women in particular.”

A more subtle example of implicit bias is found in Joanne Leonard’s Journal of a Miscarriage, 1973. The collages were meant to be a sketchbook documenting her pregnancy; after a miscarriage, she changed focus. Leonard’s collages include images from obstetric textbooks; all solely feature white babies and mothers. While miscarriage is fairly common, women rarely talk about it and often must cope alone.

The didactics and texts which are part of the artworks are often more powerful than the images themselves. As with much conceptual and socially-driven art, craft and aesthetics sometimes suffer in the service of message. With its compelling narratives, the exhibition is an exemplary work of (photo)journalism. During a public talk with the artists, the curators acknowledged the unusual amount of reading involved, citing the artists’ desire to educate us about these fraught issues. This critical observation aside, the exhibition successfully and admirably presents a thorough overview of the challenges and obstacles, large and small, women face in all areas of reproductive health, despite the landmark 1973 decision.

Reproductive: Health, Fertility, Agency is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Photography through May 23, 2021.

Featured Image: Elinor Carucci, Red #3, 2015. Inkjet print. Courtesy of the artist and Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York. The horizontal image features thick strokes of red and abstract forms, which the artist created with her own blood.

Susan J. Musich spent twenty years as an educator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago communicating fresh perspectives to non-specialist audiences. This experience infuses her approach to writing about art. In addition to freelance writing, Musich serves as a consultant to local foundations and manages the tour program at EXPO CHICAGO.