This article is presented in conjunction with Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art that seeks to expand narratives of American art with an emphasis on the city’s diverse and vibrant creative cultures and the stories they tell.

The growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts.

—George Eliot, Middlemarch (1871)

Certain intersections in Chicago remind me that every city is made and unmade. I realize this again while standing at Polk and Halsted on the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) campus, where out of place amid the brutalist buildings is a two-story red-brick house. More than a century ago, the then-abandoned house was rented by social reformers Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr. They were soon joined by more residents, mostly others from the first wave of college-educated white women, while their immigrant neighbors from Europe passed through the rooms for childcare, classes, and space.

At the time, the Near West Side neighborhood was feeding the maw of industry in Chicago—the fastest-growing city in the world. Hundreds of thousands of workers risked dangerous conditions in plants and factories to afford the suffocating “bad air” and “dark rooms” of tenement housing or the chicken-wire “walls” of cheap cage hotel rooms. Meanwhile, the rest of the world ogled their products, the steel and breakfast sausage which bore no trace of their hands.

When the doors of the Hull-House settlement opened in 1889, it was unlike any other place in the city and, beyond that, the country. There was a power imbalance between the well-off and the working class, but together they would advocate for a municipal social safety net, which until then, was nothing more than a few loose threads. Hull-House became a radical third space, a place outside work and home where people could socialize, organize, create—and, for many, feel like they belonged.

Today the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum attempts to maintain a third space through exhibitions, educational programs, and community use of its space. The museum occupies two of the settlement’s 13 buildings, the rest demolished to make way for Mayor Richard J. Daley’s visions of “urban renewal”: the UIC campus and Dan Ryan Expressway. Daley and Co.’s attempt to remake the city in 1963 drew a physical boundary between already segregated neighborhoods, destroyed hundreds of residences, and left thousands of longtime neighbors, after much protest, mourning the loss of their home.

Inside the museum, I can’t shake the feeling that I’m a ghost in someone’s home. It doesn’t help that I’m here on a slow day, wandering most of the rooms alone. Upstairs, in Addams’ bedroom, I float between her inherited grandfather clock, big-sleeved dress, and journals. On an old loom, an artist has picked up the thread of an abandoned textile. In the central room, I admire a large Alice Kellogg Tyler portrait of a woman and her baby, featured prominently above the fireplace. I move from the house to the adjoining dining hall, where residents shared meals. Maybe what I’m feeling is the hold a house has on my imagination.

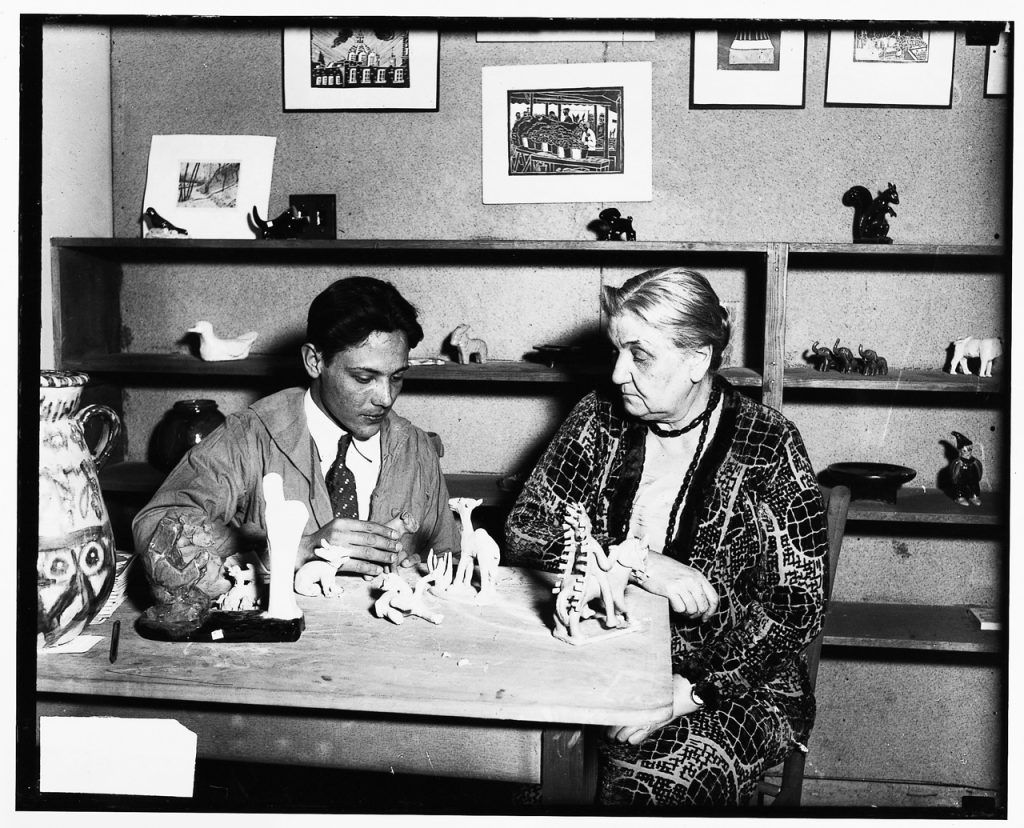

The exhibition Radical Craft: Arts Education at Hull-House, 1889-1935, draws attention to the tension between housing and home, between the public and domestic. The curatorial team has foregrounded a selection of the fiber, textile, and ceramic work made by the artisans who emigrated from Europe and Mexico and migrated from the American South. Names of these artisans wind along the staircase wall, now visible from the entryway. Upstairs, a wall of blankets, rugs, and doilies remain anonymous—not by any fault of the museum staff but by the silencing hand of the archive. Some names were never recorded.

Also foregrounded is Starr’s legacy. While Starr’s name and biography have been preserved, Addams is the one enshrined in cultural memory, sealed in the museum’s name. There are many reasons why some people are remembered and others forgotten over time, but in Starr’s case what may carry the most weight, smartly identified by historian Annie V.F. Storr, is her focus on arts education. Addams’ purview of the settlement’s sociological research located her and her work in the public sphere, the masculine-coded sphere, where the actors of mainstream history live. Starr was also an active, agitating figure in political life, but unsurprisingly, her proud identification as a socialist didn’t secure her a seat at the table of American icons.

What set Starr apart from her contemporary mainstream educators and reformers, which Addams had praised, was “her fierce insistence that artistic experience is transformational at the core of human personhood,” Starr writes, “that ‘labor without art is brutality’; that human dignity, self-discovery, and creative expression are crucial for individuals to situate themselves as citizens; that exposure to art is necessary to every child and every adult, so that deprivation is itself social injustice.”

As part of Radical Craft, the museum has been offering art classes by groups that follow a similar philosophy. Two organizations in particular, Firebird Community Arts and Red Line Service, continue to braid with this radical thread, remaking space in the city through art education.

* * *

It’s no spoiler that Daley’s revised cityscape in the sixties reinforced the unequal investment between the city’s North Side and West and South Sides. Since 1990, Firebird Community Arts (formerly ArtReach) has worked to increase access to art resources in these neighborhoods. The organization began as the nonprofit arm of a community art center on the North Side. When Karen Benita Reyes stepped in as executive director in 2012, however, she brought a lifetime of experience living on all sides of the city and a more radical approach to arts education.

“I quickly realized that access is great, it’s an important precursor,” Reyes says, “but we need to not just sit at the table but flip it and burn it and build something new.”

Thus Firebird was reborn on the Near West Side. Reyes partnered with glass artist Pearl Dick to shift their mediums to fire-based craft forms and their mission to use “art as a tool for healing.” In this spirit, they pair workshops with employment training and mentoring, trauma-informed support groups, case management, and medical treatment.

While previously working toward her doctorate in urban educational policy studies at UIC, Reyes became interested in these protective spaces, where, she explains, “people were able to connect with support and protection that kept them out of contact with the criminal legal system.” Her research and personal background as a “family-trained” or “matrilineally-trained” textile and fiber artist drew her to the history of Hull-House. Addams and Starr began to answer her questions about what white people or anyone with relative privilege could do to resist segregation, racism, and xenophobia.

Firebird will soon be moving into a new building on Homan and Lake, where they’ll be a hundred yards from other similarly motivated organizations that offer job training and services in construction, food, and art. Together they’ll form a district of third, protective space for the people who need it most, including those who are formerly incarcerated, dealing with mental illness, who are or have been homeless.

Firebird’s core instructors almost exclusively come from the South and West Sides and share experiences with their students. Some had been students themselves. As a teenager living on the South Side, instructor N’kosi Barber repeatedly switched high schools until he found glassblowing, which he says gave him purpose. Barber started as a mentor teacher in the pilot of Firebird’s glassblowing and trauma recovery program for young people injured by gun violence and is now a manager of the program and board member.

Firebird primarily serves people who have been affected by trauma, but they provide classes and training to anyone, in some cases reversing power relations that are assumed nearly everywhere else. “Some of our young artists are the teachers, and therefore, the experts, and a high-paid surgeon who drove in his Porsche is the brand-new beginner,” Reyes explains. “I’ve seen from both sides of any divide people reminded of their own and each other’s humanity and shortcomings and strengths.”

While instructors represent the people they serve, Reyes acknowledges that leadership doesn’t yet, adding, “Yes, I’m a Chicagoan, I grew up in some of the same neighborhoods, I have witnessed violence and things like that growing up, but I’m a white woman. That alone is a very distinct difference.” She’s asking questions of herself and Firebird that don’t have easy answers, questions that were never fully answered by Addams and Starr. “Where does [our] role begin and end? How do we stay in community, across differences, even as people who work together?”

* * *

Chicago ranks among the worst Midwest cities for affordable housing. For people who can’t afford housing, options are scarce. Homelessness has been on the rise throughout the country, but the number of people experiencing homelessness in the city at least tripled last year. Shelters are short on beds and usually segregated by age and gender, separating some couples and families, all of which leads many to shelter outside. Unhoused Chicagoans have unfolded tent cities in public spaces as temporary patchwork to fill the need.

Arts educator Rhoda Rosen and I first met about a block away from one of these cities in Uptown. A decade ago, she and another arts educator, Billy McGuinness, staged dining rooms on both ends of the Red Line train track. Overnight, during the coldest months in Chicago, tables, chairs, and home-cooked meals welcomed anyone who wanted to eat. Guests without housing told Rosen about the free art they would go to and places they wished they could enter and feel welcome. These pop-up dining rooms, or comfort stations, have since traversed other venues, from small galleries to the Art Institute of Chicago, growing into Red Line Service, one of the only arts organizations in the country led by people who have experienced homelessness, or “houselessness.”

Of her language Rosen stresses, “People know how to create home. Systems are responsible for not providing houses.”

Red Line Service’s relationship to space relies on crossing boundaries and transforming what’s already there. The goal is to transform the imagination of people on both sides of institutional and cultural walls. “How do you use institutional spaces, not forgo them and build a different art infrastructure—which sometimes you do have to do because the art world can be unwelcoming?” Rosen asks. “Power’s always porous, so where we can find that porousness and willingness on behalf of the curators and institutional colleagues to expand, that’s our preference.”

In general, Rosen says, institutional colleagues are trying to meet Red Line Service where they are, but there are still snags: “We often have had the situation where we’ve had the most beautiful, beautiful visit and, halfway through, I’ve gotten a phone call from a latecomer [or someone returning] saying, ‘Security won’t let me in.’”

Red Line’s community crosses culture, class, generation, and ability, which brings another set of challenges. Affordable accessible space for people with disabilities is hard to come by and can require more accommodations from partners.

The Hull-House Museum has historically served as a welcoming space to the group. As part of the Radical Craft programming, Firebird has been leading glass workshops for Red Line artists and art enthusiasts in the courtyard. At Hull-House, Red Line artist James created a glass cup for his daughter. “She loved that cup because you can use it,” he says. “That’s something she can have even if I’m gone.”

James has been involved with Red Line for the last few years, after a car crash and related disability ultimately led to him losing his job and then housing. Right away, his charm leads me to guess, correctly, that he’s an entertainer. He’s cooked and played music but never cared much about visual art until joining Red Line Service, where he’s found a sense of peace.

Also an ex-gang member, James tells me, “ I come from a place where you have to watch your back all the time.” When he’s with other Red Line artists making things, he says, “It takes me out of what’s going on two hours ago. It keeps me out of trouble when I want to get in trouble.”

At the start of Ellen Gates Starr’s essay “Art and Labour,” she addresses a chicken-or-egg question of social change. Should reformers first or only target the “ugly,” the issues of poor health, violence, and poverty that result from “the iron law of wages,” before addressing beauty and meaning? Without addressing art? Her answer, like Rosen’s, is emphatically no.

“We want to insist that the arts have a role in ending houselessness,” Rosen says. “It’s not just the advocates. In fact, very often, the arts have led the advocates.”

Red Line artist Shay Jones, a true performer, reminds me too that the movement between art and politics, between the public and domestic, isn’t one-way or one trip. I met with her and other Red Line artists after they attended a lecture, this time at Harold Washington Library, a reliable third space. Jones is wearing one of her delightfully maximalist Lotsa Pockets aprons (which is, as you can imagine, abundant with a rainbow of pockets) when she tells me about her upcoming projects as well as her grassroots organizing with Chicago Coalition to End Homelessness.

Some of the artists, like Tracy Byer, address their experience with houselessness directly in their work. “Sometimes you get lost in the system,” she reflects, “It makes you feel like you’re forgotten.” Byer has been an artist her whole life. Her abstract painting is at once about “finding yourself,” which will mean something different for every viewer. “I see myself. There’s a lot of anger, a lot of hurt. But if you look at it, you might see something different.”

William Robinson has been involved with Red Line Service since its inception. For one of his pieces, he constructed a wooden shelter and placed it in a neighborhood. He then showed someone getting evicted from the shelter, and someone moving in. It was a performance of the unmaking and remaking of neighborhoods across the city.

Remaking can be an act of mending, which Rosen believes is the work—the craft—of Red Line Service. “We’re weaving the social fabric here in this small model,” she tells me. “Without it, you can’t have politically active people. First, you have to have the imagination, you have to have an understanding of yourself as belonging to each other, and more than that, you need to owe each other.”

When I ask Robinson what Red Line Service means to him, he’s quick to say, “It feels like home.”

Radical Craft: Arts Education at Hull-House, 1889-1935, runs through July 2025 at the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum, 800 South Halsted St. Learn more about Firebird Community Arts. Learn more about Red Line Service. Radical Craft: Arts Education at Hull-House, 1889-1935 is presented as part of Art Design Chicago, a citywide collaborative initiative organized by the Terra Foundation for American Art. The exhibition is among more than 35 Art Design Chicago exhibitions that highlight Chicago’s unique artistic heritage and creative communities.

About the author: Amanda Dee is a writer, documenter, and apparition of the Midwest. She’s on staff at the literary journal TriQuarterly and, in a past life, was the editor of an alt weekly. Photo by Momoko Fritz.