In 2011, visual artist Tacita Dean opened her exhibition “FILM” at the Tate Modern where she responded to the destruction of celluloid film. She exhibited a silent, 11 minute, 35mm looped film in the London museum. The exhibition set out to provide a physical display for viewers to see the difference between digital and celluloid. The history of the moving image, important to Dean, exhibited the richness in color and the power of the projection. The New York Times writes, “Like the vinyl long-playing record, the Polaroid camera and the manual typewriter, celluloid has attracted a generation of artists who have come of age in a digital world and have developed a nostalgic soft spot for analog.”

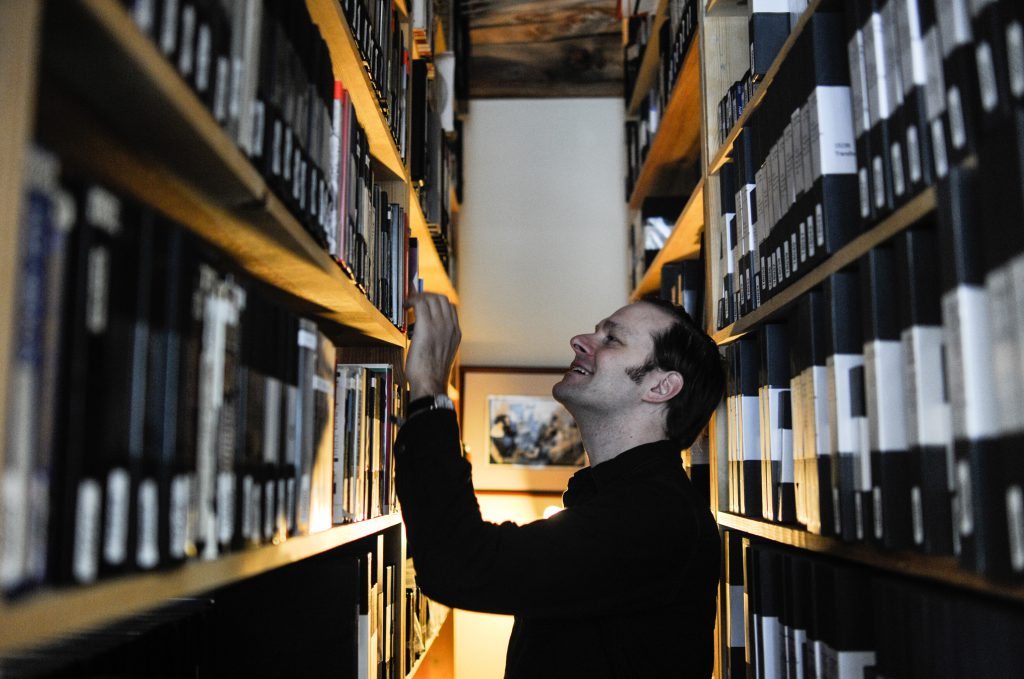

I spoke to Dan Erdman, an archivist at the Media Burn, and Director Nancy Watrous from Chicago Film Archives, about the importance of preserving celluloid and the impact of film on history.

No one ever claimed that film restoration was sexy. It’s granular. It’s a bit mundane. It’s lots of organizing and dusting off grimy surfaces. It’s protective gloves and pulling reels. It’s also an abundance of historical references. It is imperative to Chicago history, and even more so on a larger scale in cinema. It’s no secret that most of the films made before the 1950s were lost due to fires, lack of care, and improper storage. In the United States, 75 percent of the 11,000 silent films were destroyed. The devastation on celluloid is monumental in terms of historical heritage and collapsing knowledge of cinematic vision. In 1951, motion pictures were made of nitrate, which easily decayed or caught fire. Some could even explode. Two notable victims of nitrate are “Singin’ in the Rain” and “Citizen Kane.” After 1951, acetate was introduced as a non-flammable option, but unfortunately, it decayed faster than nitrate film.

Let’s look at the archival process. What goes into it? How is it done?

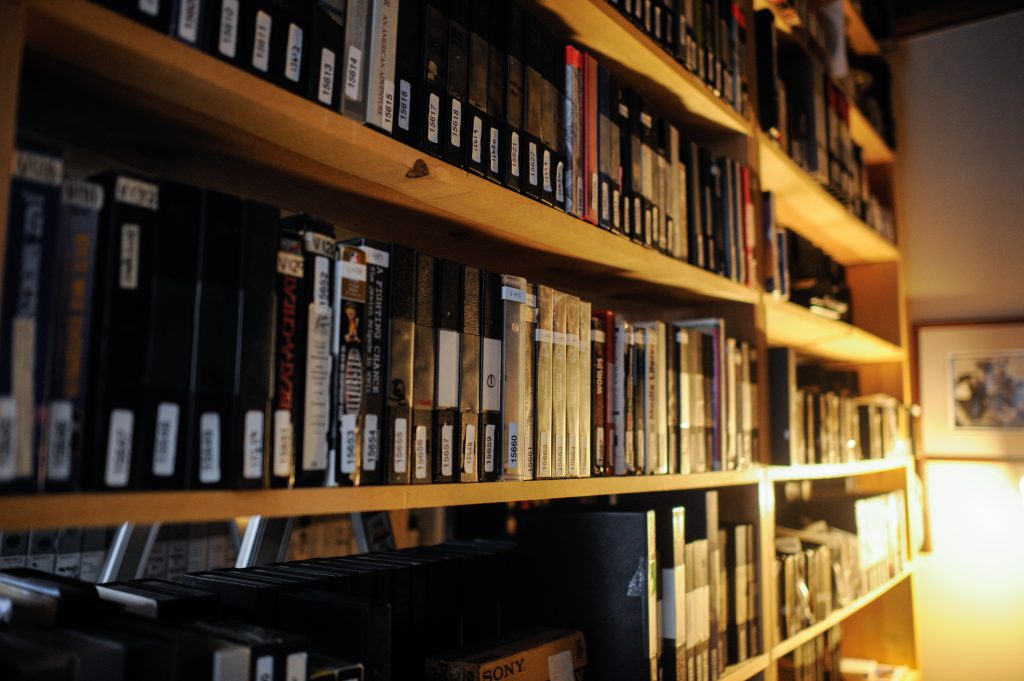

Dan, from Media Burn, explains that, “Storage, direct action on the print, cataloging, publicizing the collection, raising money, advocating for certain material within your institution, etc,” go into the process. It’s not just splicing negatives, inspecting a print, or fixing torn sprockets. It’s making sure that history is kept safe; clean, cherished, and sustained. Media Burn Archive’s mission is to accomplish just that; they restore and collect documentary video and television that were created by artists, activities, and community groups. Tim Weinberg founded Media Burn in 2003 after his 40-year-long career in production with documentaries. The archive includes 7,000 videos of a variety from video makers around the world. “The nice thing about film archiving is that it can be a passive process,” says Dan. “Once a print has been inspected and cataloged, and once it has been established that it’s showing no signs of progressive decay, it can be shelved in a cool, dry, place and left alone for many years—all you have to do is pay the power bill.”

Dan used to have a garage full of about 5,000 16mm prints when he was in his peak as a film collector. He’s been working with film for a little less than ten years. He began as an intern with Chicago Film Archives where he worked for a year. Now, Dan works with video preservation at Media Burn Archive. He says, “Video is a whole other kettle of fish.” In contrast to film, video tape will, “go bad under even optimum storage conditions, and often will do so without warning.” Sadly, he says, “within the next few decades, all video tape everywhere will become unplayable due to decay.” Therefore, digitizing is important. In comparison to the passivity of archiving film, digital information requires “constant management.”

The silver particles or color dyes in film are highly sensitive. Well maintained and appropriate environments are vital for the best preservation of film. According to the Library of Congress, a dry, cool, clean, and stable environment is the best place to store rolls of film. Keeping away from radiators and vents and making sure the film is wound securely is another appropriate procedure. Finally, a protective enclosure, “that physically support the film, block all light, and minimize exposure to dust and airborne (particularly sulfur-containing) atmospheric pollutants,” is a general guideline. For nitrate film, the Library of Congress recommends storing similar to the above guidelines, with a final bullet point stating, “consider digitizing and disposing” because of its highly flammable nature.

In 2003, Chicago Film Archives (CFA) opened it’s doors to foster and care for roughly 5,000 films from the Chicago Public Library. Issues like space and expertise caused the library to no longer care for them. Then there was Nancy Watrous, who heard about the library-film crisis and decided to find a space that would properly take care of these films. No institutions were able to take on the responsible, but fortunately, Nancy was able to create a non-profit and adopt the reels. The acquired objects quickly outgrew the original space on Lasalle–where they broke an elevator due to their weight–and moved into another space in Pilsen in 2004, where they have remained ever since. The organization is building a, “moving composite snapchat of twentieth century Midwest life,” by archiving, collecting, storing, and proudly preserving over 27,000 items.

16mm Black and White, silent film from the Chicago Film Archives. Home movie of people shoveling a Chicago street, followed by scenes of two young boys playing in the snow. Shot in the Uptown neighborhood of Chicago.

When Chicago Film Archives began in the early 2000s, they used their first grant money to purchase a telecine, a machine that transfers and digitizes home movies. The people at CFA began to collect amateur home movies from people in Chicago and in the surrounding Midwest. As a result, CFA is a part of Home Movie Day where, in the early 2000s, several archivists suggested that home movies are, “interesting films,” and that, “these films should be preserved and considered vital historical documents.” Home Movie Day is an international event where individuals bring in their home movies to watch and screen. CFA screens these films at the Chicago History Museum where owners talk about the films that they chose to screen. Nancy says, “There is probably nothing so moving (and satisfying for us) as providing people access to their past family members or even to themselves as children.”

Of course, an obvious solution is to digitize all of the film. But digital drives only have a lifespan of five or so years while celluloid, in particular, a type called estar, can last for over one hundred years when cared for properly.

Dan says that, “It would be a good thing if film scholars and historians would work with original celluloid materials rather than a digital surrogate—looking at a film print can teach you things that you wouldn’t necessarily pick up on a DVD.”

Since digital methods for storage are typically replaced within the next few years, they become a constant struggle to catch up to the rapid growth in information and storage capabilities. Moreover, digitization is not the same process as preservation. Digitization falls under the umbrella of preservation, along with storage practices and cataloging. Original rolls of film are always stored properly, even if they are digitized, in order to, “either to be shown in it’s original form or to be transferred to a more current format [in the future],” explains Nancy.

Each film in the CFA collection is looked at by hand and entered into a database. “Once the films have been inspected, they are digitized, and then the files are relegated to particular drives and backed up on others. Some of the digital files are loaded up into our website for viewing. The films themselves are shelved in our vault. When resources allow, the films are then described. This data is also entered into the database and is searchable,” explains Nancy.

“Hanging on to celluloid gives us that reference point,” says Dan. “Without the preservation of as many of the original celluloid elements as possible, we will quickly approach a situation like we have with lots of the literature of the ancient world, which comes to us having been hastily copied, translated, and paraphrased, with the originals lost to history, leaving us with something that we hope reasonably resembles the work as it was conceived.”

So, what does the future of celluloid look like for archivists, film collectors, and makers? Cinematographers are pioneering a film resurgence. Kodak is even launching a Super 8 camera which uses new super 8 film and can also be used digitally. Christopher Nolan is one of the few directors who is open to film and is championing the medium in his digital industry. Moreover, Kodak is providing a service for filmmakers, amateurs, and professionals alike, to send in their reels to be processed in the labs.

A blinking leader lady repeated ten times. 16mm print of NOBODY’S VICTIM (1972, Ramsgate Films) – described as “A positive approach to women’s self-protection which gives the latest advice on preparedness and personal responsibility.” The woman has light, wavy hair and is wearing a red blouse with a green, orange, and yellow pattern.

This brings us to the topic of underrepresented filmmakers. Nancy of Chicago Film Archives says that the CFA intends to, “bring rightful acknowledgement to the artists, artistry, and cleverness of Midwest filmmakers who, again, are often overlooked.” Scanning the channels and online catalog of CFA provides a layout of how many artists, creatives, and home-movie buffs provided a landscape of Chicago life and daily routines that would otherwise be forgotten.

All of the archiving is done in house at CFA, but audio and film preservation is outsourced. “What types of films comprise the collection? What is the content of the films and why was this content recorded?” are common questions the CFA asks during archival and preservation. Nancy says, “Somewhere buried in this data is Chicago’s history of filmmaking if you are looking for it.” By beginning with the past, the future of filmmakers is more clearly solidified, especially for those in the Chicago and Midwestern area.

Featured Image: The image shows a film reel with four women surrounding a small child dressed in light clothing. The image is in black and white. Courtesy of Chicago Film Archives’ Glick-Berolzheimer Collection.

S. Nicole Lane is a visual artist and writer based in the South Side. Her work can be found on Playboy, HelloFlo, Rewire News, Vice, and other corners of the internet, where she discusses sexual health, wellness, and the arts. Follow her on Twitter.