Chicago’s theater scene has many faces. Perhaps most iconic are several historic downtown theaters, now operated by Broadway in Chicago, with vintage interior architecture and marquees that illuminate entire blocks. Their old-school glamour contrasts with the sleek modernity of venues such as Chicago Shakespeare Theater, which boasts spectacular views of the skyline from its perch on Navy Pier. But beyond these downtown staples, it’s the storefront theaters scattered across Chicago’s neighborhoods that complete the picture of what this art form, in this city, can accomplish. As the name implies, storefronts are typically modest venues, often converted from retail outlets, that house resident and itinerant theater companies ranging from small to midsize. Firmly rooted in the ensemble ethos, digging deep for truthful performances, and drawing magic out of shoestring budgets, storefront theater-makers have gifted me many moving experiences over the years.

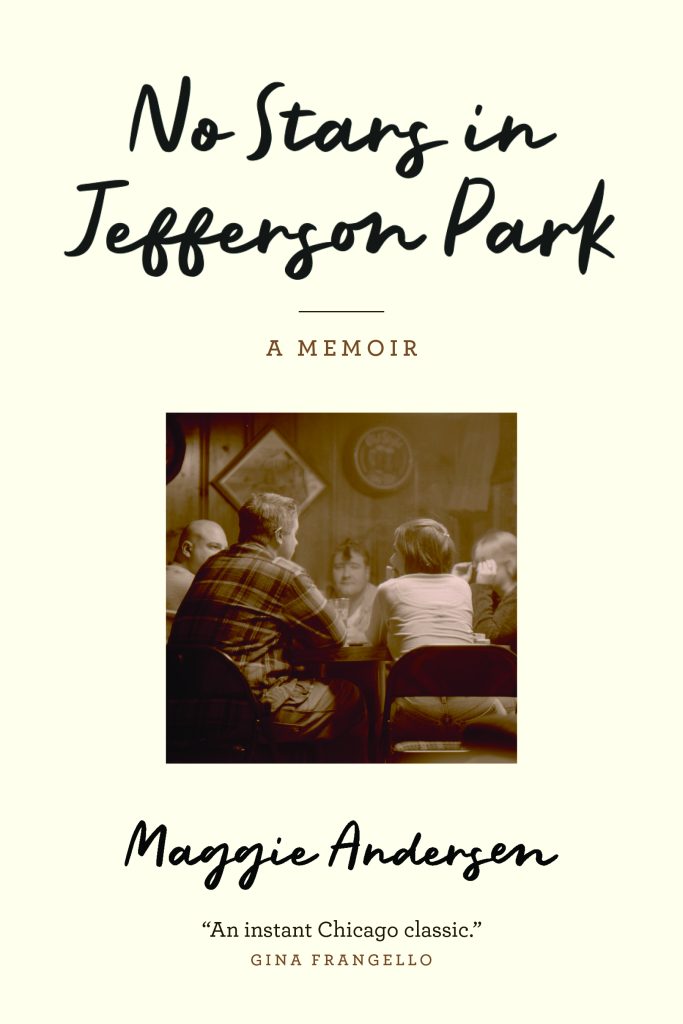

Maggie Andersen, author of the new memoir No Stars in Jefferson Park, co-founded one such company in the early 2000s: the Gift Theatre. Andersen recounts the thrill of creating art with like-minded young people, including her then-boyfriend and the Gift’s founding co-artistic director, Michael Patrick Thornton. Sadly, only two years into this venture, Thornton suffered a series of paralyzing spinal strokes, and, at the age of 25, Andersen found herself torn between her own dreams and her new role as a caretaker, experiences she revisits in her memoir.

Eventually, Andersen left the relationship to chart her own creative path as a writer and English professor. Thornton continued to lead the Gift Theatre for two decades, while his acting career progressed in theater, TV, and film. (This fall, he appears alongside Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter in Jamie Lloyd’s Broadway production of Waiting for Godot.) A tender story of love, loss, and resilience, No Stars in Jefferson Park weaves together memories of Andersen’s relationship with Thornton, their joint artistic endeavors, and her journey toward independence.

While each of these threads is compelling, I’ll admit to picking up the book primarily for its insights into the local theater scene, and it’s worth reading on this account alone. Although not intended as a comprehensive overview of the Gift’s history, this memoir succeeds in capturing the energy, ambition, and passion that drive grassroots theater-makers.

In an early chapter, Andersen recounts the electric inaugural gathering of the group that would become the Gift’s founding ensemble, who crowded into one member’s walk-up apartment to read through a script in 2001. She captures this poignant moment at the end, “We all clapped, felt a rush of pride together,” she writes. “A reading like that can be more magical than the show itself. The world comes alive with possibility. It’s like love—you can never recreate the first time. It’s like a first kiss—it can never happen again.”

The plucky ensemble rehearsed in a park district facility and put on its first production, Boys’ Life by Howard Korder, in a rented black-box theater at the University of Chicago, selling out the entire three-weekend run. Persevering through their leader’s health crisis two years later, the company held auditions in Thornton’s rehab center for Language of Angels, a 2003 production that he directed from his newly acquired wheelchair. In the following years, the Gift began to win awards and draw critical acclaim from local and national press. Nearly a quarter-century later, it’s still an active member of Chicago’s storefront theater scene and currently performs in the Portage Park neighborhood, just north of Jefferson Park.

The book’s chapters are arranged in non-chronological order, hopping back and forth between the heady optimism of the Gift’s early years and the difficult process of Thornton’s recovery. This juxtaposition heightens the emotional impact and helps the reader understand Andersen’s inner turmoil as she weighs the painful decision of whether or not to stay in her relationship. While this is primarily her story, she also offers glimpses of Thornton’s perspective through direct quotes from his emails and letters.

Andersen brings a sensitive perspective to the Gift’s origin story, not only because of her relationship with Thornton, but also due to her personal background. The daughter of a police officer, she grew up in Ravenswood on Chicago’s north side, which she describes as a “port-of-entry neighborhood” during her adolescence, before the area was gentrified. Though her working-class background often made her feel “inadequate” in the company of other actors, it also helped her relate to the people of Jefferson Park, the northwest-side neighborhood where Thornton grew up and where the Gift established its first permanent venue in 2005.

Historically a destination for first and second-generation European immigrants, today Jefferson Park is home to one of the largest Polish communities in Chicago. When the Gift Theatre opened The Glass Menagerie in its new space, a converted shoe store, neighbors came out to support their first-ever local theater. In a moving tribute to the importance of neighborhood arts venues, Andersen recalls their palpable sense of pride and ownership.

Though it’s a topic beyond the scope of her book, Andersen’s account prompts me to reflect on the uneven distribution of Chicago’s storefront theaters, which are largely clustered on the north side. I live within walking distance of about a half-dozen venues; many communities don’t enjoy this privilege. While long-established and newer companies are doing exciting work on the city’s south and west sides—Definition Theatre in Hyde Park, Perceptions Theatre in South Shore, Aguijón Theater Company and UrbanTheater Company in Humboldt Park, to name a few—the geographic disparity persists.

The idea that theater is for everyone—not only highly educated and wealthy people—is foundational to the Gift’s mission and runs throughout Andersen’s book, which closes with a flash forward to the company’s 20th anniversary celebration. Quoting from a speech she gave at the event, she recalls the first time Thornton told her about his dream of starting a theater company, when they were just teenagers.

“But I mean,” I said, “we can do that? Like, people like us do that?”

“Yes,” he said, drinking a can of 50/50. “People like us do that.”

This sentiment has buoyed Andersen through many twists and turns in her personal and professional life, as she earned a Ph.D., pursued a writing and teaching career, got married, and became a mother. She writes, “Whenever I suffer from imposter syndrome, it’s Mike Thornton in my ear, saying: ‘Yes. People like us do that.’”

. . .

No Stars in Jefferson Park is available now via Northwestern University Press.

About the Author: Emily McClanathan is a freelance arts journalist and critic based in Chicago, primarily covering theater, books, and music. Her work has appeared in the Chicago Tribune, Chicago Reader, American Theatre, Playbill, INTO, and more.