Out of Time by Cass Davis is an investigation of personal history, collective history, and gendered violence. The work oscillates between soft/tactile, and ghostly/alarming. Rooted in imagery that is (for better or for worse) deeply Midwestern, the work shown is aesthetically punctured by three-parts: textile works that hold faded images of religious revivals, assemblages of childhood objects embedded in earth and flowers, and photographs and moving images with lighting and tones that simultaneously haunt and render hyper-real. They are crisp as a recent memory yet as nebulous as a dream. Together, the works embody a personal and real vision of the American Midwest—and when I say “real,” I don’t just mean the artist’s actual experience of it, which is also undeniably present, but also real in the sense that the images and text incorporated into Davis’s works are directly from historical documents located in their hometown. Davis grew up in Pekin, IL in an evangelical Christian community where speaking in tongues at revivals was commonplace. Much of the imagery uncovered and brought forth here (and sometimes quite literally out of the dirt) are from historical archives as well as from the artist’s own history.

Three pieces lay together in cast soil on wood panels: Hidden Cross, Deadname, and Lilacs. When an object is placed in dirt, pressed into the earth, it may bring to mind one of two things. Is there a burial? Is this object in the soil in order to bury, to hide something they wish to forget? This association evokes death. However, there is a second potential when something is placed in soil—that something is being planted, it is meant to grow. The objects in these three works, such as baby teeth, a cross-necklace, and family album photos—all from Davis’s past—are perhaps summoning both meanings. We are at once our past selves and not our past selves. Identity changes as we come into our own as adults and have freedom and agency to make our own choices. A part of us is gone—has passed—but life is possible when we have space to be who we truly are. The potential of what can grow in freedom is expansive and endless.

In the piece Lilacs, there is a doubling that is repeated throughout the exhibition. A photograph of the artist as a child sits in soil surrounded by dried lilac, and underneath the photo sits another photo almost identical to the first. In the first photo, the artist’s younger self looks at the camera smiling while cooking eggs over a fire. In the second, we see the same scene. However, something is off, details are askew. The lighting is slightly different, an arm has been moved, and the expression on their face appears unsure. This doubling evokes a kind of déjà vu, an uncanny mirroring that points at the false reality that family albums—and all staged photography—capture. Is the child happy? Do the photographs reflect the memory of this moment? This doubling forms a glitch, a rupture between memory and constructed history.

The repetition of images also appears in Davis’s pieces Revival II and Presence. Revival II shows two black and white images of a crowd of people at a revival. The scene is chaotic and blurred with hands in the air. Again, both images are almost identical. Like Revival II, Presence also shows similar images next to one another: a close up of a man’s ear with another person’s mouth right behind him, slightly open as if whispering. These two images also come from a revival scene. Although the two pairs of images are similar, the method in making the pieces leaves room for error, anomaly, and difference. Presence is rendered from hand screen printing the images onto textile and Revival II was created by Jacquard weaving the cloth by hand. Through these methods, it is almost impossible to create two identical images. History, too, is handmade—written, constructed, and pieced together by those in power. What details are missing from these images? What context is lost? By revealing these scenes to the audience, Davis is unearthing events from the archive that many may not know about while uncovering elements of their past.

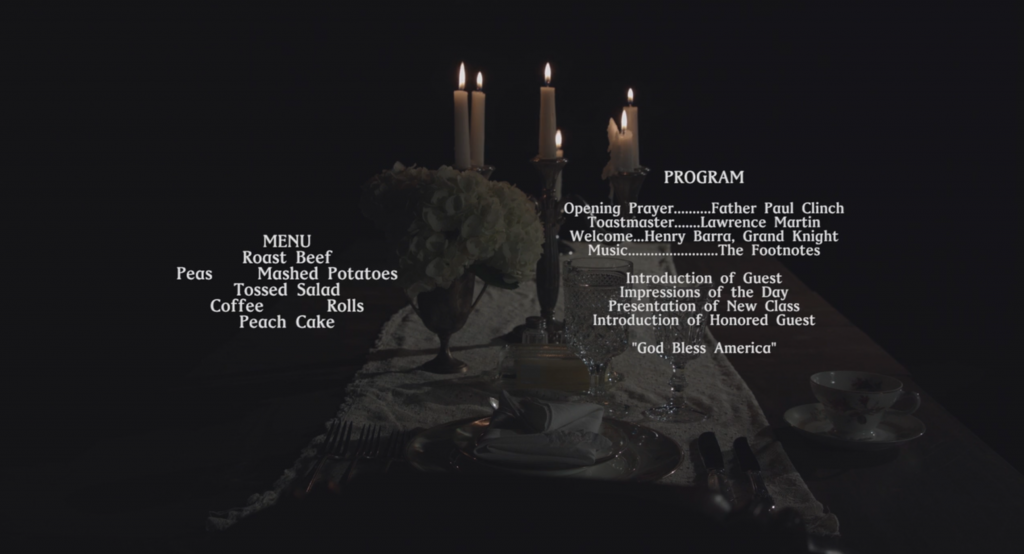

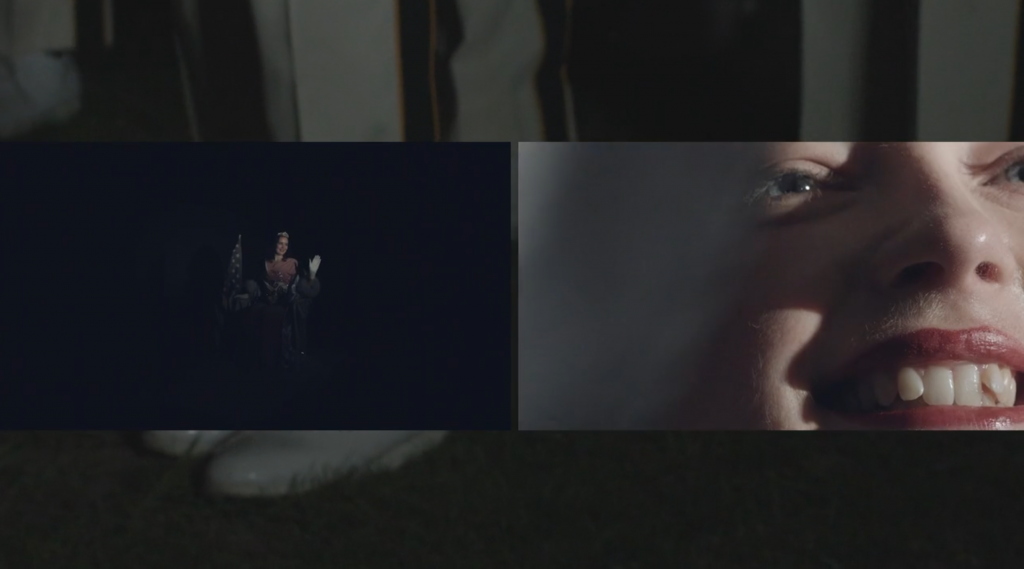

These pieces and fragments are also woven together through images and text in Davis’ knockout film Sundown, Reprise, 2020. A standout piece in the show, the film offers us scenes of parades and young women in white gowns on a split-screen. An eerie tone sets the stage in lighting that makes everything appear almost black and white, but not quite. We see a marching band beat silent drums, a candle-lit feast laid out on a wooden table, and a strange, altered version of the American flag. Text periodically comes across the screen; one memorably appears to be from a church bulletin, complete with the day’s program starting with the opening prayer. The text and images come directly from the archives of the artist’s hometown of Pekin, IL. Although the images are staged, they are inspired by events lost within history, forgotten because of their ties to racism and violence. Here we see again this uncovering, an unearthing that Davis enacts throughout the exhibition as they point to what is intentionally not shown to us while also revealing what they have chosen to forget from their own past for self-preservation.

Yet it is not self-preservation that has compelled those that have written history to exclude certain details and events. Whether tragic and violent events are excluded, or the stories, lives, and voices of those who are not deemed valuable by white America, these exclusions are meant to be edits that benefit the author and enact violence onto those they have harmed.

To wander through a place and/or state of mind one has intentionally left behind is by no means easy. Here, Davis wanders and discovers, searching through archives and personal possessions as a means of extraction, to pull apart these structures in place for the potential of a better future. Like the bare feet carefully shifting weight, stepping back and forth, forward and backward in the beginning scene of Davis’s film Sundown, Reprise, 2020, the artist bravely and without hesitance moves forward and backward throughout and within their history as well as our own, stepping in and out of time while facing down structures of oppression.

Out of Time is on view at Aspect/Ratio from October 3 through November 14, 2020.

Featured image: Installation view of Out of Time at Aspect/Ratio. A large installation/textile piece is on the right side of the gallery, and smaller photographs and mixed media pieces are on the left. Image courtesy of the artist. Photo by Nick Albertson.

Christina Nafziger is a writer, editor, and curator based in Chicago. Her research focused on performativity within the image and the effect archiving digital images has on memory and identity. Her recent writing investigates the work of artists with research-based practices as well as the role of the archive and its capacity to alter and edit future histories.