Featured image: Rebecca Beachy, Mice Bones, 2022. Image centers a pile of mice bones the artist gilds with copper and various metals. Image courtesy of the curator and artist.

In Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957), the world has turned upside down; time, the rhythms of life have become unbound, daily cycles errant and unspooled when the knight Antonius Block returns to a Sweden decimated by the plague. Block wanders in a semi-fugue state after he both perpetrated and witnessed the holy horrors of the Crusades. He soon meets others inerrant and lost and their makeshift, misfit group is soon haunted by Death’s pale shadow. Life, both its presence and absence, its fragility and persistence, its burdens, its responsibilities, its needs, its heartaches, all that is unbearable which we are called upon to bear, lies within the story’s stubborn heart. For a moment the group escapes Death’s tendrils and stops to rest. It is during this all too brief picnic where Block is touched by the pleasures of milk and strawberries, the joys of nature, and the sometimes surprising, welcome simplicity of the heart’s wants. He states, “I’ll carry this memory between my hands. . . it will be enough for me.”

What does enough mean in a world marked by suffering? What happens when the beloved memory drips to the ground, the sigh ends, the gate shuts, your king is in check, and confession does not make a difference? What do we do when we are lost, and it seems as though the path will never again appear? Here is the truth, with the sparkling glass profile of an aphorism, and the warm weight of the numinous: “this too shall pass.”

This Too Shall Pass, curated by Joshi Radin at the Ralph Arnold Gallery, is a poem, a quartet between curator and three featured artists: N. Masani Landfair, Rebecca Beachy, and Nancy D. Valladares. Taking cues from the exhibition’s title—the phrase’s origins in medieval Sufism and the kinship to curator Helen Molesworth’s 2012 exhibition on the sociocultural shifts of the 1980s under capitalist realism, This Will Have Been—the artists’ works speak to the entanglements, the knotty impossibilities of living and dying in a world marked by capital, a world that clings to the false hope of stasis as a necessity for consumption. Think “business as usual” or “getting America back to work” during a pandemic that laid bare the vulnerabilities and material inequities upon which modern life is built. Landfair, Beachy, and Valladares’ work not only complicates but challenges such discontinuity; all three engage time and cycles of materiality and immateriality to ask, “do you not see yourself in these assemblages, these remnants, these memories, these moments of the natural world? You should, as these are your actions, the chain of reactions, echoing out from their point of origin.”

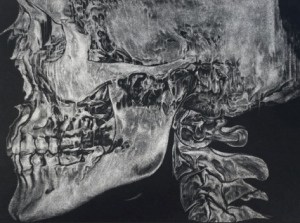

In Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents, the world as we know it has ended. The destruction of the natural world alongside an economic system predicated upon inequality has laid waste to America. Lauren Olamina, the complicated heroine of Butler’s books, presents the Earthseed religion as a way forward. The religion itself is built upon the truism that the only constant is change, that as change defines our world, “God is Change.” Change is the prime mover for Beachy’s corpus of work; a priori and a posteriori alike, the deep-set knowledge that new growth and entropy are conjoined, bedfellows forever intertwined. In keeping with Beachy’s practice as a taxidermist, their work is comprised of organic material—owl pellets, copper strains, bird nests, mice bones, clay deer droppings—which the artist then transplants to sculpt, to measure, to mend, to experience. It is a process which highlights the inevitability of both new life and decay. Beachy’s Mouse Bones pieces or Owl House (the bird’s nest in question transplanted to one of the ceiling tiles of the Ralph Arnold Annex) form a continuum, both forgotten burial crypt and cathedral rafters; they are explorations of liminal spaces, of the care that is desperately needed yet rarely provided.

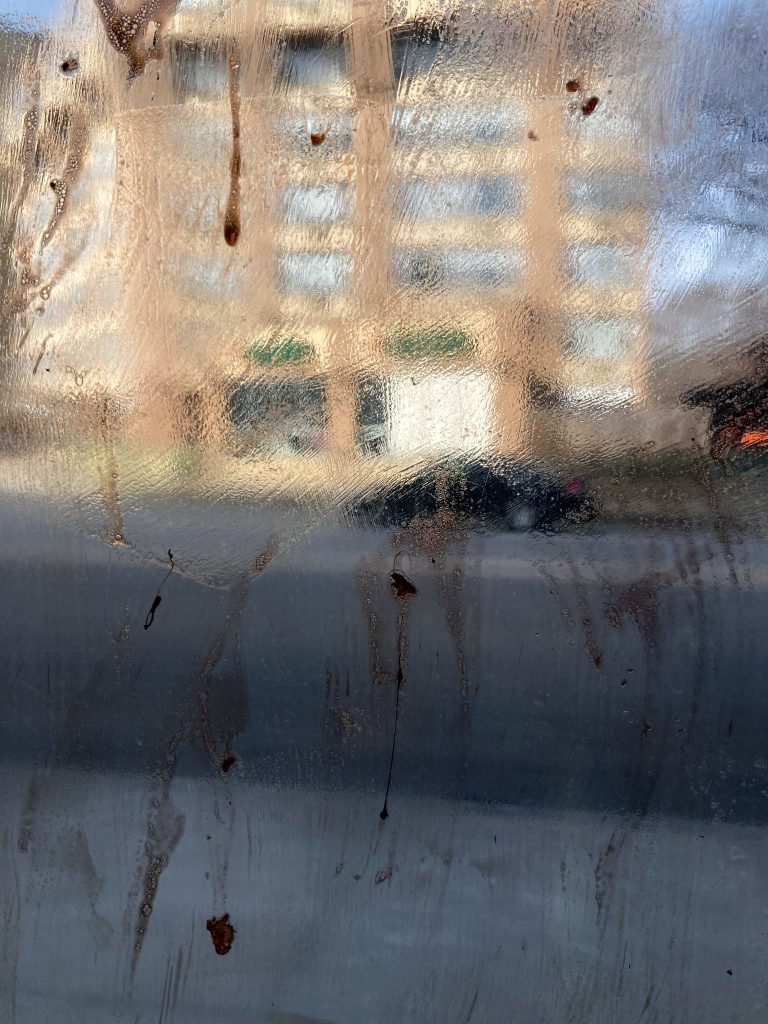

There is a profound sense of ephemerality in Valladares’ work; it’s the fragility of both time and material, that ever-present tension between change and the freeze of a single flash bulb. When viewers stand in front of the artist’s Silver Window Gelatin, an obfuscation occurs. Depending on one’s vantage point, the piece offers waves, an undulating view of sight into the Annex or out onto the Loyola campus. The world is a bit more still here, it is a moment in time where you hear nothing. That silence, that nothingness, beyond lies the distant ringing of a bell tinkling with substrata of silver and nitrate. Valladares’ own artistic practice is heavily intertwined with photography, their work engaged with the friction between the materiality and immateriality of the image, and the exploitation inherent to photographic practices. Think the violences of extraction, mining, pollution, and the gendered and racial labor dynamics inherent within. It is the legacy and transmission of art, of visual culture, that Valladares has found and bottled in their Silver Beaker series in various states of stasis and eruption. The human and nonhuman touch closely here, boundaries begin to blur.

This melding of spaces, both material and immaterial, is a predominant theme in Landfair’s Sixth Extinction collage series. An artist in deep communion with shared histories, Landfair is deeply influenced by their own family’s unfurling relationship to the industrialization of Chicago and their grandparents’ roots in the American South, and the reverberations of Great Migration. Taking images of landscapes in flux, changed by human presence, alongside manufactured materials, Landfair engages the social structures that provide for such seismic shifts in humanity’s relationship to the environment. Landfair’s practice considers how the precarity of labor, of environmental care, both travel hand in hand with race. There is a pervasive sense of isolation within Landfair’s landscapes, some are populated with human figures but often they are alone, or it is a space unpopulated, empty of human beings. Yet, at times Landfair also suggests the freedom of such spaces. The psychic, affective elements of the work present how life can change, that where there is desolation, there is also potential. Where there is destruction, there is room to rebuild. Worth is not a constant in Landfair’s work, rather it is an instrument of sight. A way to understand anew, see what was previously hidden by blinders, only possible through a glimpse.

We are here then at the way things are and the way things could be, This Too is a proposition. The entangled possibility of gentleness, a way of living in the world that has no referent, an interwoven sense of connection that you and I share something and that something should be protected. There is a debt here, what we owe one another, what we owe this earth; the land, the homes, the communities that nourish and sustain us. There are bonds that must be honored. The time is now, for nothing lasts forever.

Annette LePique is an arts writer, educator, and archivist. Her research interests include cinema, race, illness, and the body. She has written for ArtReview, Newcity, and the Chicago Reader.