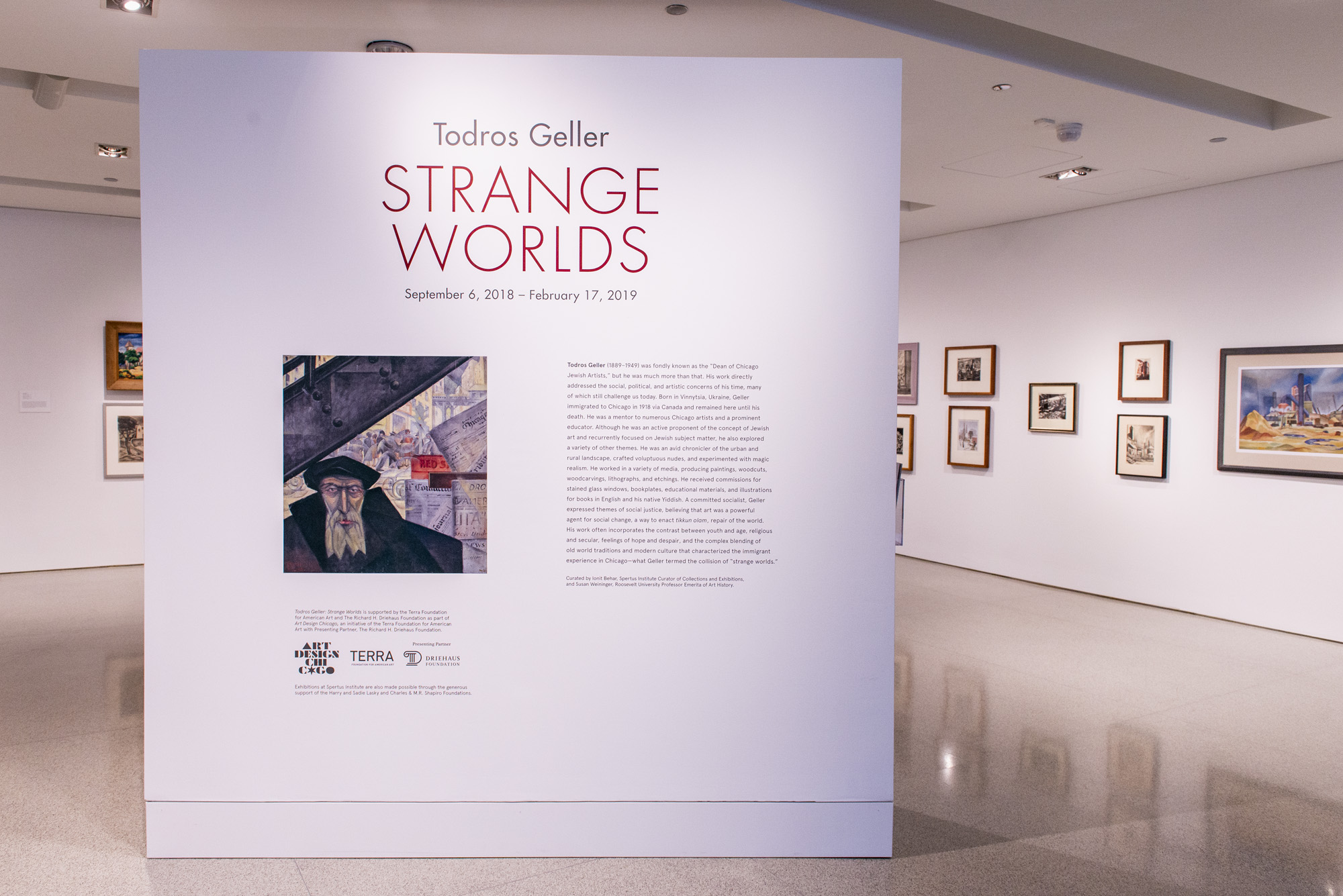

Todros Geller, (1889-1949), was a Jewish-American artist born in Ukraine, immigrating to Canada and later Chicago in 1906, where he studied at the Art Institute of Chicago. He became a prominent artist during his time, having a hand in many organizations in Chicago and working with such artists as Charles White. The exhibition Todros Geller: Strange Worlds showcases the diverse work—in style, subject matter, and medium—that Geller created throughout his lifetime; and is hosted at the Spertus Institute of Jewish Learning, an organization that began as the College of Jewish studies, where Todros Geller taught for many years. Many of the objects from the exhibition come from the institute’s extensive collection of Jewish art and historic, ritual objects, a collection that Todros Geller began. Co-curator of the exhibition Dr. Susan Weininger explains Geller’s interest in Jewish art, “One of the things that [Geller] pursued his whole life was the idea of a Jewish art museum. He knew that there was a history of Jewish art [and] he traveled to study that history.”

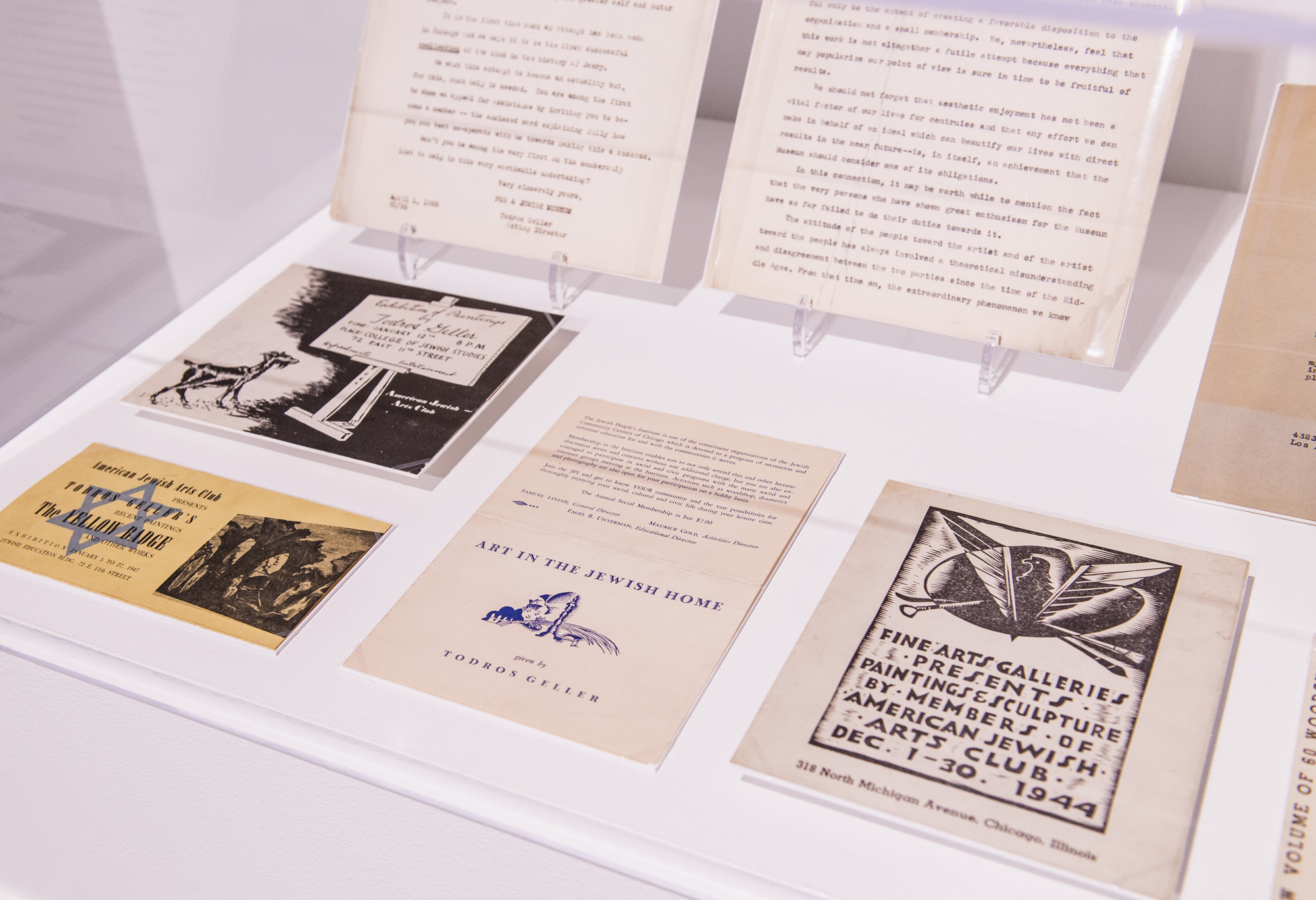

Dr. Weininger and I walked through the exhibition, stopping at paintings, prints and documents illustrating the picture she was painting for me of not only Geller’s history, but the history of the Spertus and its collection. “Geller made 150 of these particular woodcut prints [Yiddish Motifs, 1926], which he made himself on this Japanese wood grain paper. They were published in a portfolio– 150 copies of the portfolio sold out quickly. He took the money he made and went to Europe, to England, and then to British Mandate Palestine in 1926 and created some work. These three paintings right here [Jerusalem Beggar, Untitled (two men), and Jerusalem Courtyard] were inspired by that trip to Palestine. He went with the express purpose of finding examples of Jewish art that he could include in the lectures that he came back and gave all over the place. He gave these lectures in Yiddish and sometimes in English, and he talked up this idea because Jewish people, even smart Jewish people, have the idea that Jewish people never made any figural art–which isn’t true, not even into the late 20th century. Geller had this mission to start a museum of Jewish art. And he did. And It’s Spertus. That’s the museum. It happened.”

Before walking through this exhibition with curator and art historian Dr. Susan Weininger, whose curatorial research has for years focused on Chicago art history, I expected the exhibition to be a survey of an artist’s work, simply highlighting Geller’s artistic accomplishments. However, it proved to be much more than that. The immediacy of its relevance as it pertains to the life of an immigrant struck me. Geller reaches for a sort of belonging, as he simultaneously lives in two worlds: the place he came from, and the place he wants to belong. As Dr. Weininger and I discussed how Geller’s Yiddish Motif prints became common imagery in many Jewish homes even today, she claimed that this was just one half of the story; there are two sides of the coin being shown in this exhibition.

Dr. Weininger explained, “Part of the story is the Jewish world, part of the story is the world of America, which was a world of promise–a world that offered the hope of being assimilated. You know, there was always this push pull. [Geller] was other, but he was not other–he didn’t want to lose the other, you know, an immigrants challenge. And I don’t know how far back you go, but everybody’s an immigrant here. I like to say everybody, even if you came on the Mayflower because there were people here before, meaning Native American. In Geller’s work, and you see this clearly in his painting Strange Worlds, there’s this tension between the new, modern world, that world in the background with the futurist style, and the old-world person in the foreground. The man has his back to the new world. So there was this fear of complete assimilation. We don’t want to give up that part of us that is from our tribe or our group or whatever. And on the other hand [for Geller], there is this possibility of becoming, in this case, a real artist in the mainstream world–not being part ghettoized, really.”

As we make our way across the exhibition, we pass several paintings with palpable human emotion; a painful struggle that displays the difficulty surrounding the immigrant as well as the laborer. Geller not only portrays the suffering of his own people during the Holocaust but also the plight of the laborer. The social and political activism that began showing up more and more in the 1930s was ever present in Geller’s work, as well. “Often the Jewish immigrant was someone who was not attached to ritual,” explained Dr. Weininger, “but there is a piece of that Jewish tradition that certainly survived. That piece to me is the idea that art can change the world, that you can use your life in service of repairing the world.”

As we approached the end of the exhibition, I found myself surprised at the sheer range of styles that are represented in Geller’s work, which included magical realism, surrealism, and futurism. A painting [Michigan Ave Bridge, 1930] with a heavily cropped composition caught my eye, perhaps influenced by photography. Dr. Weininger, while mentioning Geller’s nude works that she was fond of were excluded from the show, was drawn to this image of the Michigan Avenue Bridge as well, saying, “I’ve always loved this painting. It’s a modernist American painting. This is the kind of style that American artists had adopted in the period right after World War One to glorify, to show how wonderful and modern the American city was. It wasn’t a European style, it’s really an American style called Precisionism. What I love about this piece is that Geller put these two little people in it to humanize the whole thing, and I just think that it’s really a wonderful painting. So this is his American side coming out. He was simultaneously [painting] these Hassidic dancers and the Michigan Avenue Bridge. They’re just two sides of him.”

The space holding the exhibition is quite unique, with one entire gallery wall a zig-zag; an almost serrated edge created by sheets of glass from floor to ceiling. Covering this glass wall are reproduction images of stained-glass windows Geller designed. These images created a remarkable effect as they overlaid the artwork inside the gallery when viewing it from the outside looking in. This layering created a multiplicity of imagery that was not so unlike the layering of histories woven throughout the exhibition, revealing the intricacy that is the historical landscape of Chicago. Pointing at the stained-glass imagery, Dr. Weininger mentions that one of these is actually in a Synagogue she frequents, the Anshe Emet Synagogue, which commissioned the piece to be designed by Geller and fabricated by Drehobl Art Glass Co. This company, founded in 1919, is still in business here in Chicago because of this commission, along with another designed by Jewish artist Raymond Katz, which saved them during the great depression. As we continue our journey through these historical events, Dr. Weininger explained how the commission was done in a response to anti-Semitic vandalism that damaged their synagogue’s previous stained-glass window.

At the end of the exhibition, we gaze up at the image of Geller’s piece The Liberty Window, as Dr. Weininger says, “This window was specifically about the Jewish experience in America. The other windows were all historical scripture, biblical scenes, etc. […] In the center, there’s a deck of a ship. There’s a bunch of people looking out over the port of New York. They can see the big buildings. They see the Statue of Liberty. On one side is Abraham Lincoln on the other side is George Washington. This is the same kind of theme that we see running throughout Geller’s work: the promise of America and the promise that America offered to immigrants like him, and like some of the others who were coming in a far more fraught time. And the community was committed to this idea of being Jewish and American.”

The timeliness of the tone of the exhibition hit me hard, asking myself, what has changed since Geller’s time and what has not? How many images have I seen that show the same struggles of the immigrant today? Dr. Weininger, who also volunteers at the Holocaust Museum in Skokie, suddenly tells me a story she heard told by a Holocaust survivor.

“There was one survivor who told a story, he was an orphan. He was 10 or 11 years old when he came to the United States at the end of the war, and he tells his story. He said, ‘I came and I looked out over this harbor and I saw these big buildings to my left, big buildings to my right. And in the middle, I saw the Statue of Liberty. And I don’t even know how I knew what the Statue of Liberty was,’ You know, he was a kid, but he said, ‘But I knew I was in a place where I was free.’ And that’s what it’s about. We have to keep it free.”

This article is presented in collaboration with Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art exploring Chicago’s art and design legacy through more than 30 exhibitions, as well as hundreds of talks, tours and special events in 2018. www.ArtDesignChicago.org.

Featured Image: A view of the exhibition Todros Geller: Strange Worlds. A white wall within the gallery has an image of the painting with the tile being exhibition’s namesake. This image is of an older, Jewish man wearing traditional clothing facing the viewer, with a bustling, modern city street behind him in the background. The words Strange Worlds are on the wall in red. Photo by Ryan Edmund Thiel.

Christina Nafziger is a freelance arts writer with a background working in curation, arts administration, and community outreach. Earning her M.A. in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths University of London, her area of research focuses on performativity within the image, virtual identity, and cyborg theory.

Christina Nafziger is a freelance arts writer with a background working in curation, arts administration, and community outreach. Earning her M.A. in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths University of London, her area of research focuses on performativity within the image, virtual identity, and cyborg theory.