“Intimate Justice” looks at the intersection of art and sex and how these actions intertwine to serve as a form of resistance, activism, and dialogue in the Chicago community. For this installment, we talked to Liz McCarthy about shifting from photography to sculpture, the performance of making objects, and pleasure as resistance.

S. Nicole Lane: When did you start creating art in general? What’s your educational background, how did you end up in Chicago?

Liz McCarthy: Sure. I went to the University of North Carolina at Asheville. And when I was there I was doing photography with mixed media. I was super into photography and the dialogue of gaze and kind of taking/capturing the moment and these documents of experience. I also dabbled in clay a little bit, because there was such a big clay community. Then I moved to Chicago in 2009 and started Roxaboxen Exhibitions, which was an art space in Pilsen. I ran that for three years. I’ve also worked with Acre for a long time—Acre is a residency.

I’d say my work has shifted a lot—was shifting a lot then—from photography to sculpture and working on the surface of photographs, and thinking about photographs as a substrate for additional reactions—a physical reaction. Right before I went to UIC—I started UIC in 2015—right before I started I went to Banff residency in Canada and did a residency there where I started on this project with whistles. It was this push into a sculptural place and a performance place. I was thinking about whistles as these sort of archetypal objects. My dad used to use them to meditate and then I used them to play with as toys. They’re objects that can change meaning in whatever context it’s in because it’s an object that has this noise attached to it.

I’m starting a ceramics studio in Pilsen next month.

SNL: So your practice is primarily working with clay?

LM: No. I would categorize my work as sculpture and performance, mixed with photography. I’ve been using clay because it’s a thematic material. It is a material that humans have used for over 30,000 years but it is also used today and has a contemporary context as a material. It’s also very similar to human bodies where it holds impressions and it’s also sourced from the earth. So there’s a lot of reasons why I started using the material, but I definitely am not a ceramicist. I am engaging more in a conversation around sculpture.

SNL: Okay. So you said that you had a problem with the ceramic community in North Carolina? Can you maybe talk about that a little bit more?

LM: I think I got really turned off from clay because it was so married to tradition and craft, and it also uses so much cultural appropriation. So many people I knew were obsessed with Japanese tea bowls, and making Japanese tea bowls, and doing the Japanese tea ceremony. That felt weird because, well, they’re not Japanese and, “Do you even drink tea?” What’s the context of this? I’m interested in the ceremony and ritual aspect but I think that there’s a difference between origin and use and that division. You can make a lot of work about those two barriers. I got really turned off from that, and also felt like I didn’t want to make a tea pot.

SNL: Yeah. And also North Carolina being so craft-oriented.

LM: Yeah. And traditional, and a bit conservative…

SNL: For sure, yeah. Yeah, so your work changed when you moved to Chicago?

LM: Yeah, for sure. My work definitely changed, but I think it’s been a slow progression. And I was actually making a lot of work when I moved to Chicago about North Carolina because I was really missing it, being in the city and being removed from nature in the way that I’d had access to it in North Carolina. I was making a lot of pictures—like making this whole series about the moon and taking 23-minute exposures of the moon and then drawing, cutting up the surface of these pictures, and thinking about how I could have a natural connection to the earth even though I was in a concrete jungle.

SNL: Yeah. How has the Chicago community influenced your work?

LM: I mean, infinitely. [laughter] It’s so much more of a richer and more intellectual community, I think. It’s also really self-aware. I think in Asheville I was really frustrated by how insular, and white, and hippie everything was. You know, I liked it there because it was kind of queer and punky, too, but it felt very much like it didn’t know what was happening in the rest of the world…at all. And it was so frustrating. In Chicago, you know, you have lots of social issues and so, I think I thrive more in a place that I feel like I’m participating in conversations rather than just playing out the same thing.

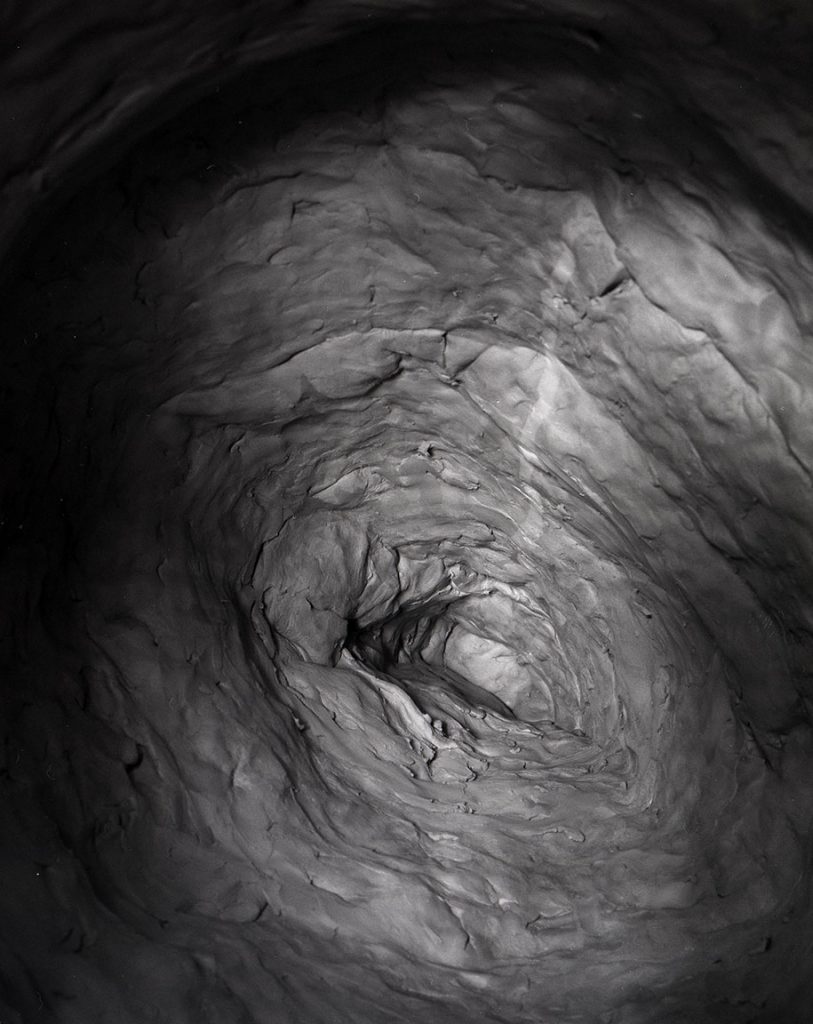

SNL: Yeah, yeah. So, let’s talk about your clay pieces and your installation piece called “The Pen.” It kind of reminds me of some sort of archaeological dig but also the shapes are very organic and, you know, crumbling, falling apart.

LM: Totally, yeah. Recently someone described it and said that it looked like “scatological play,” and I really liked that. That piece is actually related to the video in a lot of ways, where in the video I was thinking about sort of these traditions of craft and how, in craft, you’re taught to do these certain physical activities that lead to this end that’s participating in this tradition of making, and tradition of making the object that’s similar to these other craft objects. “The Pen” was sort of thinking about play and in craft, there’s an end. Especially in ceramics, there’s the vessel, which is the end product.

In this piece, a lot of the vessels get broken and smashed and sort of fall apart. The entire thing is made out of traditional ways of building, like coil pot building, pinch pots, slabs, and these different ways but then pulling those apart and playing with the materials. The other important part about those is that they’re on a carpet, and thinking about the home or like this carpet that—for me—registers very much with growing up in the suburbs of Chicago. So many places were carpeted and it was this place to keep your body safe and clean and warm. But then sort of using this material that’s pulled from the earth, that’s traditionally made to make vessels for the home but then destroying—messing that up—and bringing that material back in to smear into the carpet and to build on the carpet. I was thinking about this synthetic carpet base and then this naturally occurring material and the push and pull of those two places and then this relationship to play and building things up and then fall apart. Then afterwards, in something that I call a “performance,” which is just this act of making, I’ll bring in other people and tell them what to do with the material. They’ll kind of play with me and they usually take a week long to make. And then, afterwards, it just exists. It’s also thinking about this site, an archaeological site, and this activity of a human that has been archived as sacred.

SNL: Yeah. The relics of play, basically. And you said it related to the video?

LM: Yeah. It’s definitely about “What were the expectations of the end product?” but then, “How did those fall apart?” And then also re-thinking space, re-thinking these sacred spaces like the carpeted house versus the archaeological dig. In the videos, it’s more explicitly engaging with these traditions of craft. I’m jerking off with clay materials. “Mature Female Making Handles,” is handle-making. There’s one more in the series that’s called “Mature Female Making Pinch-Pots.”

https://vimeo.com/201301443

SNL: Right. Yeah. I think because I primarily write about sex and women’s health, I’m obviously looking at those videos and I just see…sex, you know? Because that’s how it looks through my eyes.

LM: And I can talk about that.

SNL: So it’s interesting. I didn’t even think about traditional form making and clay. I just saw this really beautiful illustration of this old anatomy book and it’s showing how a penis is formed and how it begins as a clitoris. And somebody had said, “I didn’t come from your rib, you came from my clitoris!”

LM: Mmm-hmm.

SNL: And so I was thinking about that when I was watching “Mature Female,” because I had just seen that illustration a few days before–

Liz McCarthy: Yeah, that’s amazing!

SNL: It starts out as this concave shape and then forms into this phallic figure.

LM: There’s an Anne Sexton poem I really like where she writes, rather than Eve coming from the rib she falls from a star. [laughter] She fell from some random planet.

SNL: Clay is very sensual. Like in your whistles, they’re very organic shapes. Can you talk about how working with clay is a sensual practice for you, or for the viewer?

LM: Sure. Yeah. I mean, I think when you talk about clay, you talk about it as a body, and different types of clay bodies. You’re very intimate with the material and with the whistles you’re connecting this thing to your mouth.

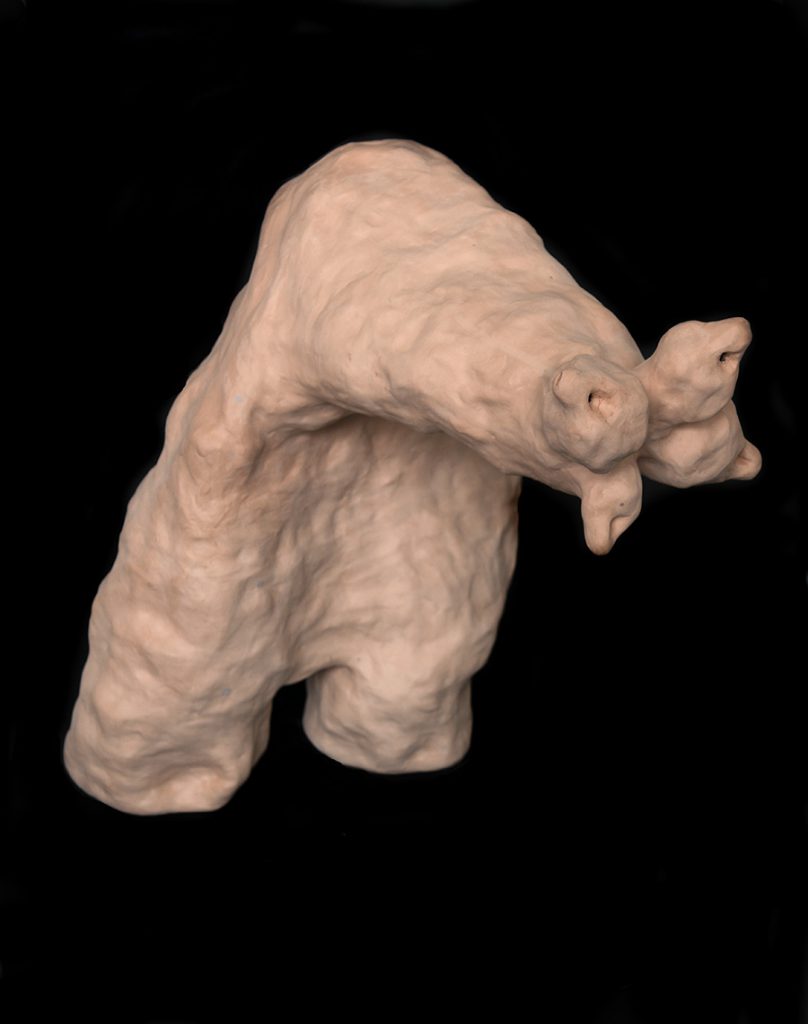

So, it’s absolutely sensual. I’m like obsessed with touch, and physicality as a form of communicating. I’m really interested in embodiment and also disembodiment and I think that play is a way to do both, where it becomes this form that you’re working with and making something out of and like using your body to manifest a form. But then the form itself takes on it’s own life afterwards—which is maybe just what happens with sculpture in general—but I think just the way that I touch clay— don’t use tools a lot, I use mostly just my hands—and so it’s a very physical activity. And recently I’ve been trying to build my whistles even bigger so that they’re more physically imposing, where I really have a physical relationship with my objects. Even using the objects afterwards they become hardened creatures.

In “Whistles Built for Many” I definitely think about the positions of the body and how that relates to embodiment and disembodiment. With those pieces, you have to collaborate to use them, so multiple people play the same whistle and collaborate their bodies in order to be on this object. The intention of that is for people to have to twist and use their bodies in ways they’re not used to and collaborate in ways that they’re physically not used to. I think that when I’m directing these performances—and I’ve only done a couple so far, but—it’s asking people to think about the positions of their bodies in sex, and childbirth, and care-giving, in labor, as in physical labor. I think, for me, it’s not just about sex but sort of these familiar ways of moving your body but also making those un-familiar. How’s the material put to use? How is the body put to use?

I mean sex is the most explicitly used in the “Mature Female” videos. Those are all based on pornographic scenes. I watch a lot of porn for entertainment. So in those videos I’m thinking about these expectations you have in a porn. My body at my age and race, I would be categorized as “mature female.” I wouldn’t actually be categorized with a race because I’m white and then I’d be “mature female” because I’m like over 28. [Nicole laughs] I might be like a “MILF,” I might be like a “slight mature female,” too, because I identify with that category. I was sort of thinking about the way my actual form—or my body, or my material—was categorized, and then thinking about these expectations of gaze within—and also performing those expectations, and performing these sort of physical actions. I think that clay or craft has a gaze to it, where it’s like you have these expectations of what the material is and what it’s going to do. By kind of merging the two, I feel like it’s starting to confuse them both.

Within “Mature Female” you have the vaginal close-up masturbation shot and then you have—or I guess it would be more just like a sex shot—and then you have the hand-job shot with the handles, and then the last one, which is “Pinch Pot” is more just like a fingering.

SNL: So, back to the performances that you do with the whistles? Can you describe that a little bit more?

LM: I started with single-tone whistles and this kind of more collective everybody’s-happy-hanging-out kind of way. And then I wanted to push the proximity of bodies together and also the proximity to collaboration and push into a place that was more uncomfortable. I started making whistles that were embedded in a larger clay body. They have several different mouth holes in them. They instigate a lot of eye contact or sharing something if it’s heavy but then it’s also these bodies that become really intimate because you’re really close to the person and can smell their breath. [laughter] Usually when I do those performances it’s in a restricted area and I’m usually just on my hands and knees and kind of thinking about these bodies—these positions—also the body being vulnerable and being intimate. With those pieces it’s definitely referencing positions of the body in sex but I think also positions of the body in sex translate to all sorts of different kind of ways of being.

We’re all physically divided by computer screen. I mean, even right now we’re divided by a computer screen. We’re mediated through this more digital technology. I’ve been thinking of these bodies—these clay bodies—as being objects that are mediating multiple people that can come together and harmonize and de-harmonize based on the ways that they’re playing the instruments. In the same way I think of sex as being a collaboration or something that you’re doing on your own.

In sex, even in pornography, the material is the body—the female body. You’re changing the body from a resting state to a turned-on state. This material transition of the body where you’re touching yourself or touching somebody else, you are distributing blood to a different place, there’s more saliva. It’s sort of like, in female sexuality, the bladder becomes full. There’s this transition or this change. And it’s similar with clay, where you’re moving and changing.

SNL: Yeah. Changing shape. Was this your first time working with video? With the “Mature Female” and the other two pieces?

LM: I did a video before grad school that I don’t know if I’ll ever show again. I like doing performances for the camera. I think about them as moving photographs. I still definitely use photographs to document performances but I don’t think photography’s still really important to me. I think that the videos are not so much videos as much as they’re straight-up photographs that are moving.

SNL: Right, yeah. So would you ever, or have you ever, done a performance in front of an audience or in an exhibition? Other than maybe, I’m guessing, the whistle pieces are done in front of people. But, for example, the “Mature Female,” would you ever do that in front of an audience? Or have you?

LM: Uhhh, no. With those ones I like the idea that they were in the same format as pornography. That was why I chose to have a fixed gaze within that piece. I was using the vernacular of pornography to make the video. Like with “The Pen” pieces, people can view those as both the making and participate in it. Like I sort of think of participation as watching the performance. And then with the hang-outs—the whistle hang-outs—they’re participatory but they’re still a performance.

I like performance a lot and I like the network of doing the performance and having the artifact of the performance and having the document of the performance. I think that those are all important elements within the performance because I think that those are just ways we interact with the world right now in this very specific way. We don’t just have our action and experience. We have the artifacts of that experience, we have the documents of that experience, that experience is mediated by this, this, and this, and that’s all very sculptural.

SNL: Do you view your work as a form of resistance or not?

LM: Pleasure is a site of empathy. Pleasure can be a site of resistance. Like in Lacan, desire is this kind of social expectation. I think that pleasure is really deviating from that and also pushing a lot of boundaries in a really explicit way. I’m in a very hetero relationship. I have not always been in a hetero relationship and I think that it’s really important to hold your body in many different ways and I think that sex, especially female sexuality, can be a really powerful way of talking about the body as a tool and also a weapon. In the same way the camera is a tool and a weapon. The way in which we hold and perform our bodies can be a really powerful way of saying “We’re not going to follow these rules that you’ve set out for us.”

The “Mature Female” videos are pretty explicitly doing that and also in all of my work I’m thinking about the verticality versus horizontal kind of understanding of a social experience. The current administration and politics in general seem to be very vertically oriented—it’s about hierarchy and status—where, I think that, within these sort of performative elements and trying to create the body… being very horizontal, in horizontal positions and… I mean, I think sex itself is just this amazing thing because a lot of times it’s done horizontally and changing the body in these different positions.

I mean right when Trump got elected I did a piece that was just like a sleeping bag and it was like a self-portrait. Just kind of this crumpled sleeping bag on the ground. You know, thinking about, “Yeah, my body is laying down in hiding and but also in this comfortable place.” I was thinking about traditions of back-to-land-ers and escapism.

I think it’s really important to make sexual work, it’s really important to talk about sex all the time, and I would even take it farther. A friend of mine said a really funny thing about my work, where he’s like, “In you our work resistance isn’t futile, it’s fecal!” [both laugh]

Sex is really messy and disgusting, and the more disgusting and messy the more fun it is. And I think that—in life—the more disgusting and messy it is the more fun it is. And I think that would be my politics as well. [both laugh] That’s why I like clay because it’s messy and falls apart and can be broken and kind of reconstituted. I would say that the material cycle is in line with my metaphysical belief system.

Featured Image: Courtesy of the artist. A still from the “Mature Female” series features the artists legs spread open with a large mound of clay in the center. Two hands are shaping the clay into a phallic shape.

S. Nicole Lane is a visual artist and writer based in the South Side. Her work can be found on Playboy, HelloFlo, Rewire, SELF, and other corners of the internet, where she discusses sexual health, wellness, and the arts. Follow her on Twitter.

S. Nicole Lane is a visual artist and writer based in the South Side. Her work can be found on Playboy, HelloFlo, Rewire, SELF, and other corners of the internet, where she discusses sexual health, wellness, and the arts. Follow her on Twitter.