Intimate Justice looks at the intersection of art and sex and how these actions intertwine to serve as a form of resistance, activism, and dialogue in the Chicago community.

Hyde Park resident John R. Harness wears many hats: he’s a creator of table-rop role-playing games that are aggressively gay, a blow-job extraordinaire, and an expert Klingon speaker (helping coin the first term for the LGBTQ community). I met John at his apartment over the summer where we sat between his two cats in his living room and discussed gay bathhouses, fascists, and what heteronormative spaces can gain from gay spaces.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

S. Nicole Lane: So I don’t know really anything about games…

John R. Harness: My work is in the realm of table-top role playing games. I learned about Dungeons and Dragons when I was a young kid—I was like 6 or 8. A friendship of mine deteriorated because my friend’s father had been into D&D and introduced me to it and suddenly that was all I wanted to do, and my friend was like, “I don’t want to do that, that’s boring,” and it was like, “Great. Can I hang out with your dad?” [laughs] You know? It’s a game in a sense that there are rules—but we call them mechanics, sort of the ways that numbers interact—but it’s also just about storytelling.

So everybody’s probably heard of Dungeons and Dragons, but the world of role-playing games is much broader than that. There’s a ton of different kinds of sub-communities and, you know, the games that I’m producing right now are very sort of artisanal, hand-crafted micro-games, that maybe three people have played or have any interest in playing, right? As opposed to something that is meant for maybe a mass-market audience. That’s what I do.

Now, I am producing a little bit of visual art aimed at people who go to galleries and the art market and things like that, but not a ton of that has to do with gameplay per se. It has more to do with my interest in storytelling and words—I’m a textile artist. I’ve made a handful of very small tapestries, I’ve built several looms in my life, things like that. But the one place that these do cross over is that, in 2015, Bryn Pernot, Grace Needlman, and I co-curated a show called “At Play: Rules, Roles, Rituals” at Corner Gallery in Avondale. And that was an exploration of the intersection between art—from sort of the art world angle—and games and play. We invited artists who were people making games or engaging with rules or engaging with role-play as part of their artistic practice. That was super cool. I made a ton of connections through that. Something that I’m trying to do is to get them to intersect more. I want them to intersect more. So I’ve put myself in the middle of them.

SNL: Do you draw from certain types of games to make your own games? Or which ones?

JH: So, a lot of what I’m doing now is what, in the design community, we call “hacking,” which means taking a game that already exists and taking it apart and putting it back together—maybe with a different story behind it or in a different setting or something like that.

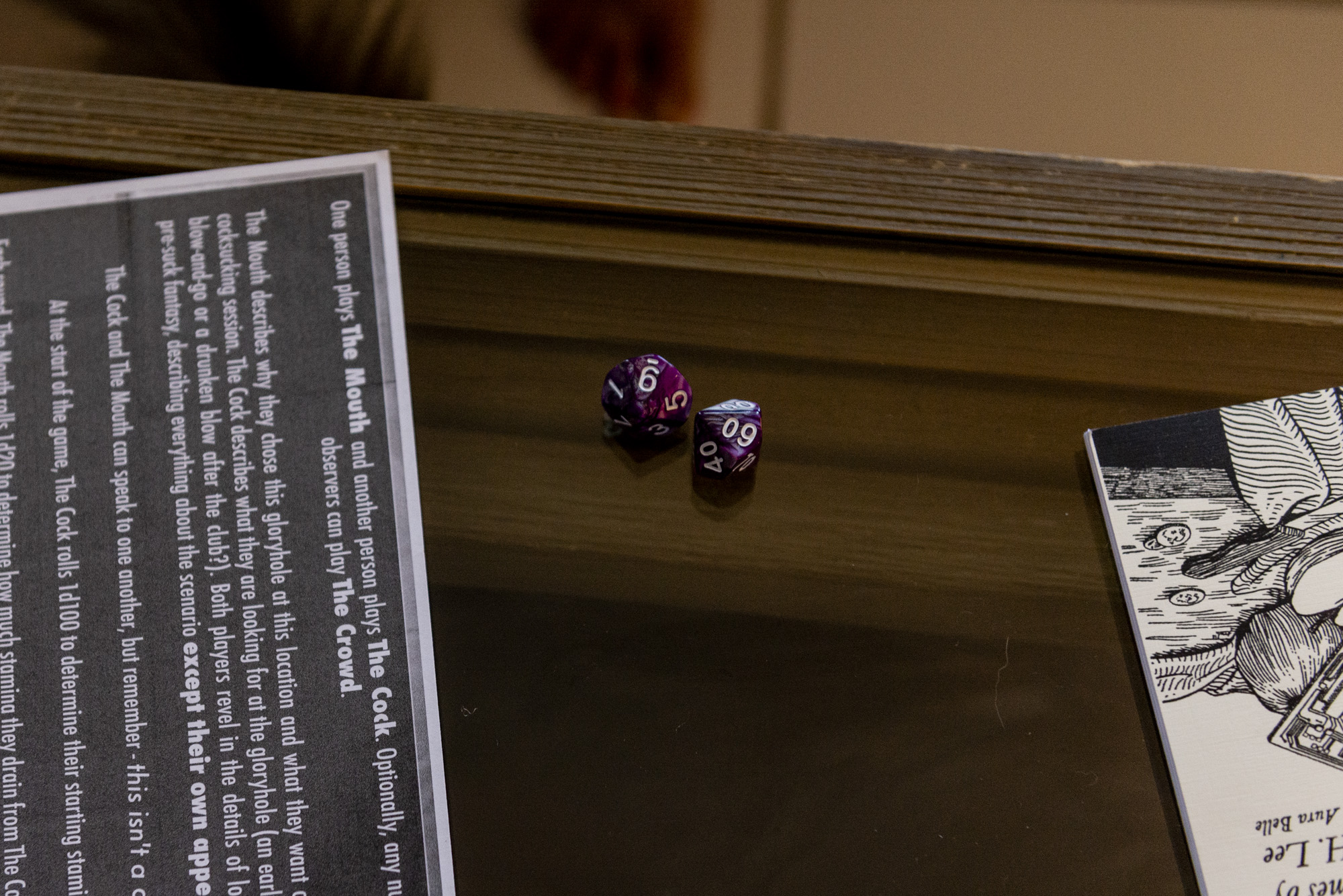

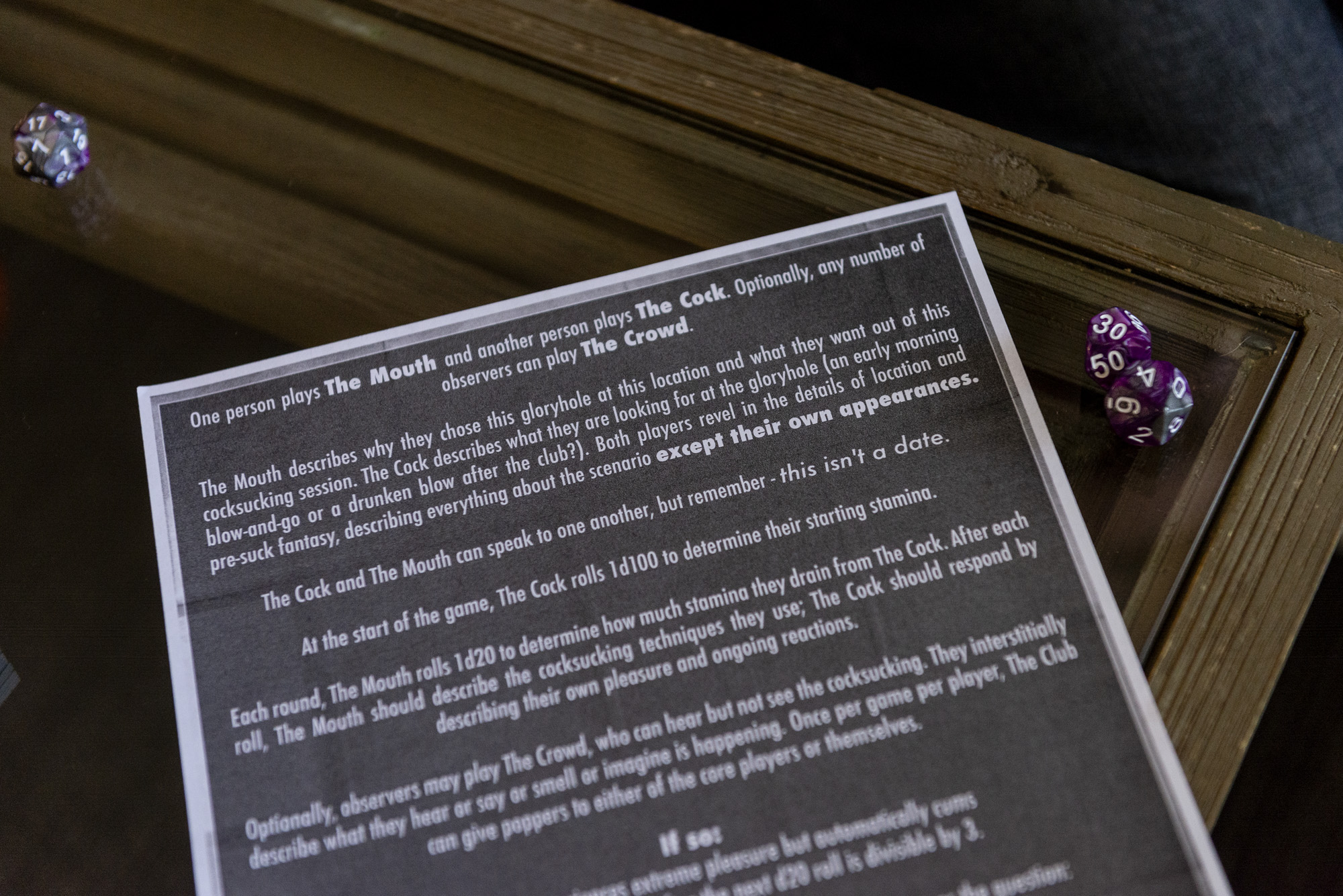

So I took C. Leary’s “There Is No Way Out of This Arena” which is a fun little micro game— it’s just a micro game because it’s just two little pages long, maybe it’s only one page long. It’s very small, the literal write-up of it. It’s a game specifically where you lose. It’s about gladiatorial combat. And you go into it knowing that, if you are playing the gladiator, this will not be a triumph-escape action movie where you get out. You know the end of the story is that you die. The game is about what it’s like to go through this process of knowing you’re about to die and sort of lengthening or truncating that story in a way that is engaging. And I was like, “Hey, that reminds me of blowjobs.” Because you have an end goal in mind and you’re always sort of edging, literally, how long do we want to draw this out and how quickly do we want to get to the explosive ending, so to say? So I took that game [and] modified it slightly. I worked with a really cool designer named Mabel Harper to do some of the design of this little one-page piece of paper and made it about anonymous cock-sucking in a bathhouse setting. I guess it’s not technically in a bathhouse setting, but I think I started that way and moved back. So you can have a blowjob wherever you like!

SNL: Can you talk about the themes in your games?

JH: There’s tons of sexual imagery and sexual stuff in role-playing games. There’s D&D games that have rules about how to have sex with stuff, but they’re kind of like the naughty, wink-wink, like, only your older cousin owns this, right? And they’re only on the secondary market. There has always been sex in role-play, and there have always been sexual role-playing games. What I’m trying to do is draw on my own sexual history, which is a lot different [from] many of the people involved in roleplaying games, and say, “Hey, if I mine this for interesting content and interesting ideas, what do I find? And, via the mechanism of this game, can I share those ideas with you in a way that I can’t when–” So, for example, I can’t take you into a gay bathhouse.

SNL: Yeah.

JH: For example. Or maybe, I could, but it would in a way change the whole experience. Right? And some of that’s good, and some of that’s bad! I wrote a game called “The Pit,” which is a supplement for a really good game called “Dialect,” a game about language and how it dies, by Thorny Games. Very briefly, that game is about a group of people who are part of a community that is going away. Over the course of the game you come up with the slang or jargon that [each] community uses. It’s a metaphor for the way that real-world languages are dying and stuff like that. And I said, “Hey, what’s a community that I know that is sort of vanishing? Answer: Gay bathhouses.”

I love gay bathhouses. I started going to gay sex spaces in college and I find them really interesting for a lot of reasons. And so I wrote “The Pit,” where either the bathhouse is simply going to shutter and close permanently or it’s being transformed into less of a gendered, sort of, single-sex space, so it’s opening up to different gender expressions and things that it has historically. Both of these represent a, sort of, end to the community that’s there and [each] have their pros and cons of different varieties. So, in that, the themes I’m trying to get at are like, the realities of gay identity—I identify as a gay man. So in my life, in the last 20-30 years, gayness has changed very much! Right? In a way that I kind of want to crystallize it and be, like, even if it’s just on these three pieces of paper, I want to grab this one kernel of what it’s like to be in those spaces, preserve them in amber, and maybe then be able to show and share just a tiny bit of that with people.

So there’s the kind of conservative preservation angle going on. I think that gay sex and gay spaces have a lot to teach straight people or straight spaces. There’s a lot of good things in the ways that relationships are forged in those spaces and ways that sexual lives are forged, not only as preservation. I want to be like, “Hey everyone, look at this! You don’t even know this exists, but can I blow your mind with what goes on in these spaces?” You have walked by Steamworks in Boystown a hundred times. It’s right there. You can go in. And this stuff is happening there.

I think a lot about AIDS victim Scott Burton, who was a performance artist and a sculptor. He made, like, the most corporate-looking furniture so that people would buy it. And then sometimes, but not always, it was a joke! In the “Art, Aids, America” show there was this bench that he made—or chair, really—there were these two pieces of granite that were kind of interlocked in this way so that they were holding each other up. And you’re like, “That’s cool, it’s sort of a math problem. Also, they’re definitely two dudes fucking.” Like, very abstractly. Like, if two Tetris pieces were banging. [Nicole laughs] That’s what they look like. But only if you kind of know the secret, do they look like that.

I want to preserve these things but also I want to kind of be like, “Here’s this little gem of gay sex wisdom…and I’m just going to put it riiiiight…here! For you to find! Find it later!” I think about that a lot. Other things that are in the work, I think a lot about power play. My game—the one that’s based on “There’s No Way Out of This Arena,” which is called “Welcome to Paradise, Baby”—is about the power play inherent in blowjobs, where often in gay sex discourse the power dynamic in a blowjob is like,“I big cock haver shoving it in your mouth. You’re the faggot sissy cocksucker. Fuck you. Suck my dick.” Right? Whereas, I, a happy cocksucker, of the highest order, I’m like, “I’m the one who could bite your dick off right now.”

SNL: Yeah! “It’s in my mouth.”

JH: Yeah. There’s a ton of power here. You know. And you’re the one who has come to me, right? I don’t need you. There are other dicks to suck in the world. [Nicole laughs] So there’s a lot of interesting power dynamics in there, so I like talking about that kind of thing. You know, the idea of topping from the bottom.

SNL: What’s the process of game writing? What does that mean?

JH: Well, it’s a good question, because one of the things I’m interested in role-playing games is that I’m not really sure what kind of media they are, and I think that’s because they’re a kind of distinct thing. When you say you’re making a game, you are simultaneously saying, “I’m writing a book. I’m making a document. Here’s my document,” but you’re also saying, “I’m setting up an event later for some people to do a thing, but I’m not really writing that story, but I’ve written the game.” So I think game writing is a lot like writing a musical score, or maybe like writing a play. It’s not exactly like that, but I think it’s similar in that you’re writing this sort of set of instructions to be followed. Games are interesting because they’re weird reference documents. Like, some of the games that I’ve been writing are these tiny things that are like, “Here are some instructions, imagine this, talk about this, role a dice, then, the end.” But some of the bigger [games] are huge reference documents, with multi-page tables of contents and stuff like that.

SNL: And how long does it usually take you, roughly?

JH: Well, the night Trump got elected, I got really angry, and I sat down and I shat out a two-page roleplaying game that’s called “Us Faggots Kill Fascists.”

SNL: Yeah. I think I read on your website that you want these games to live– Well, not “live,” but be on PornHub? Is that correct?

JH: Yeah, I’ve been thinking about that!

SNL: I love this!

JH: I both want to take gay sex stuff into gaming and art spaces, and I want art and gaming stuff to be in gay sex spaces. I saw just some porn videos on PornHub where one guy is playing Mario while another dude blows him. And I was like, “I can do that.” And, what does that mean? And what does it mean if I do that and I get paid $15 on a subscription basis on Only Fans? And can I tell my aunt about that at the family cookout? [Nicole laughs] Okay, what if I do the exact same thing and show it at an art gallery and a collector buys it? And then can I tell my aunt about that? You know?

Those kinds of questions I’m really interested in probing. And what the framing of these different things mean. Can I get a bunch of gamer people to sign up for an Only Fans, when Only Fans only exists for pornography, right? What would that be like? I’m interested in the– I bring up the “tell my aunt?” because I’m thinking of my literal aunt, who’s a very sweet lady, who’s long-suffering. [laughs]

Some of these things we can talk about and some of them we can’t. This is what interests me about violence and about explicit sex. Some of these things I can talk about at my day job and some of them I can’t. Some of them I can talk about in polite company and some of them I can’t. But, at the same time, it’s like, okay, I’m supposed to be making art and, in art, we’re supposed to draw from our deep, aesthetic experiences, or we’re supposed to draw from our feelings, or we’re supposed to cause other people to have deep feelings. Okay? Well, the deepest fucking thoughts I’ve ever had I had while blowing a dude through a fence. Okay? Like, there we are. [Nicole laughs] And I am being flippant about that, but, to make the point strongly, that I’ve had real, meaningful experiences in these spaces and I want to be able to draw from that and express that. And yet—“don’t talk about it. You can’t talk about it.” Like, I’ve gotten over sadness, I’ve processed deep thoughts, I’ve lost time and blacked out—all of these things, in the wonderful Disneyland of gay bathhouses, for example. And that is kind of like having a secret life. Because I can’t put that on my resume. “Expert cocksucker” and “Proficient in Microsoft Word.” [Nicole laughs] Like, you can’t do that. And I’m interested in why that is.

Featured Image: The camera is focused on two die sitting on a brown wooden table. Somewhat cropped out of the composition on the right side is a small book with text and an illustration. On the left side of the composition are the instructions to the game. Photo by Ryan Edmund Thiel.

S. Nicole Lane is a visual artist and writer based in the South Side. Her work can be found on Playboy, Broadly, Rewire, i-D and other corners of the internet, where she discusses sexual health, wellness, and the arts. She is also an editorial associate for the Chicago Reader. Follow her on Twitter. Photo by Jordan Levitt.