David Bernie (Ihanktonwan Dakota – Yankton Sioux) utilizes historical and current events within his artwork to create dialogue across communities. The subject of Bernie’s work is predominantly social and economic inequality, both within Indian Country and worldwide. He is driven to comprehend the roots of inequality while inspiring discussion and action.

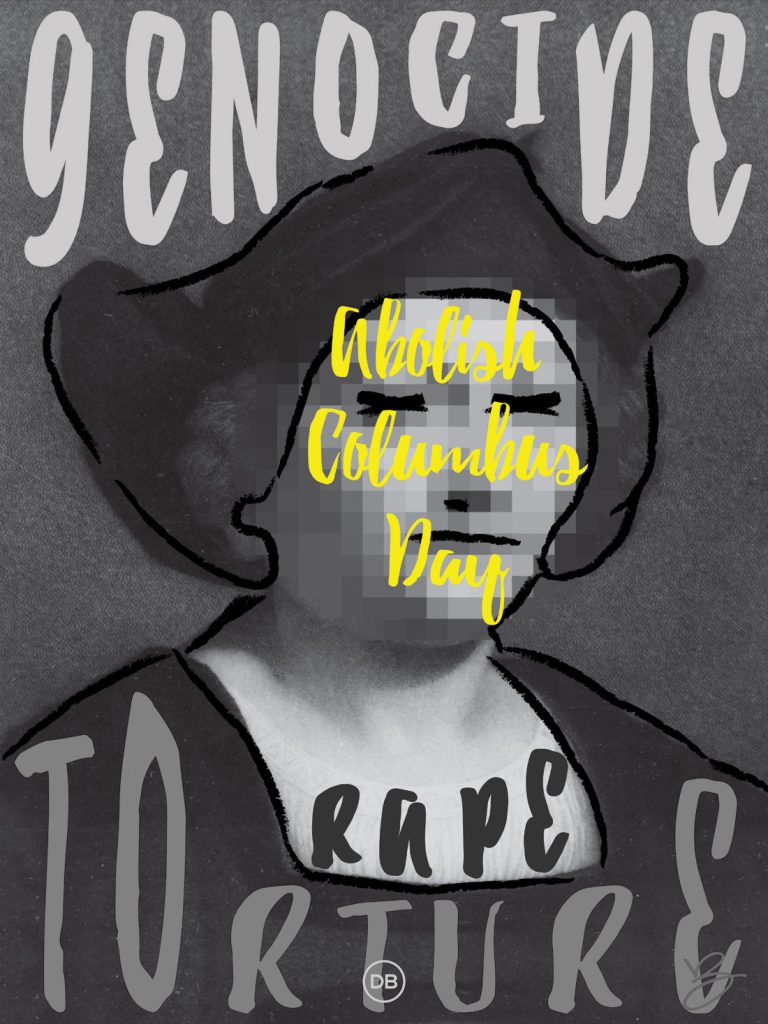

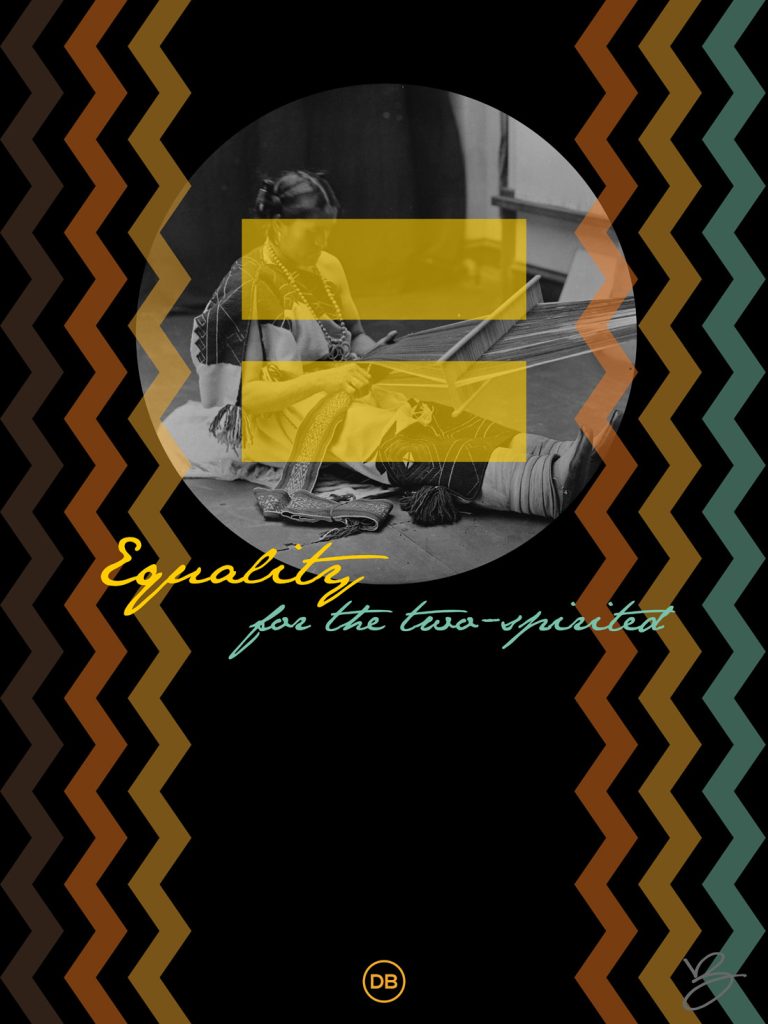

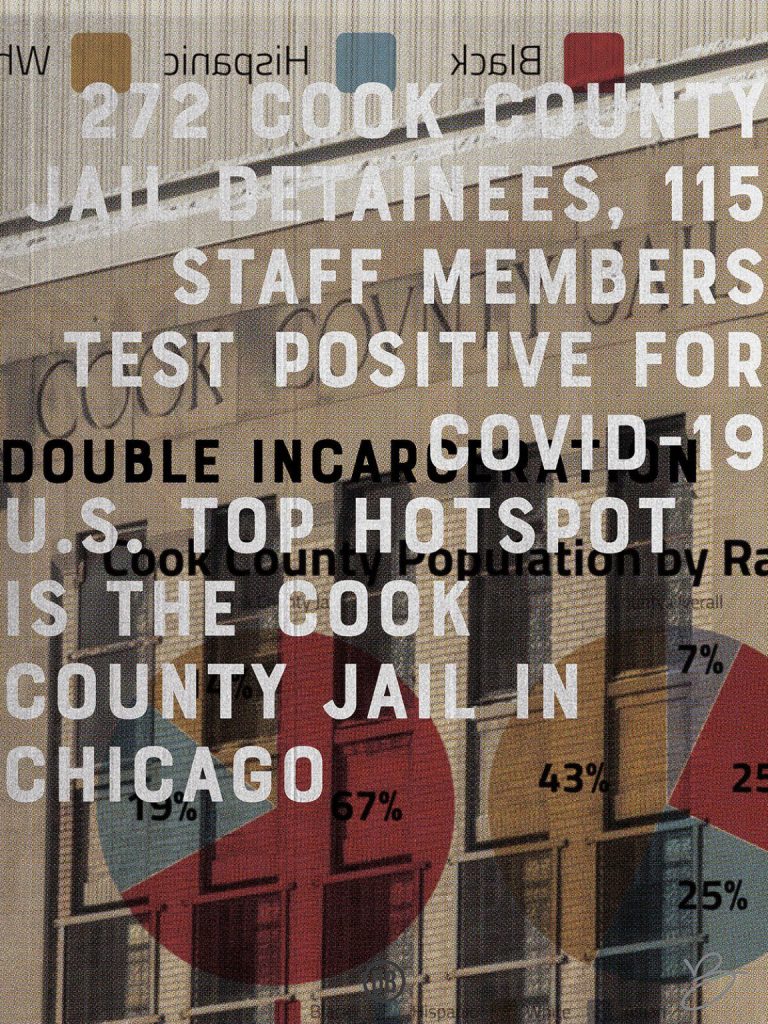

In much of his work, Bernie layers together graphics representing historical moments and current events. Through a powerful dialogue between image and text, he reinterprets the relationship between the past and the present. His collages address a range of pressing issues, including Native American and Indigenous Rights, Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, historical silences, Native mascots, Native stereotypes, and inequalities affecting Black, Indigenous, People of Color, and queer communities.

In Bernie’s words: “I aspire to create through the inspirations that surround me — from thoughts to visuals. I capture images with cameras, document thoughts with a pen & paper, create visuals with colors and textures, and illustrate my life through the medium of art. I do not live in a tipi nor was my great-great-grandmother an Indian princess. I do live and breathe native identity, the inherent desire to combat ignorance and misconceptions, and the preservation of culture.”

Analú María López (Guachichil/Xi’úi), a Sixty contributor and the Ayer Librarian and Assistant Curator of American Indian and Indigenous Studies at the Newberry Library, an independent research library with a focus on rare books, manuscripts, and other archival materials. She recently sat down with David Bernie to discuss his artwork, inspirations, and future projects.

Analú Lopez: Tell us a little about yourself — where are you from? Did you grow up in Chicago?

David Bernie: I am originally from Chicago, born at Cook County Hospital, and raised on the north side. Most of the Native American community lived in Ravenswood to Uptown, with Wilson Avenue being the main corridor and the American Indian Center being in the middle. My mom would take me to daycare at Truman College, and families would plan get-togethers at each other’s homes or parks and beaches. Growing up, the Native families worked in the community, looked out for each other, and attended the same schools.

My mom would send me to stay with family on my reservation in South Dakota in the summers. I would spend time with my dad’s side of the family, and I’m grateful for having both an urban experience and a place I call home. I am Ihanktonwan Dakota (Yankton Sioux), and my tribe is in the southeast corner of South Dakota, two hours from Sioux Falls.

AL: How did you get interested in art?

DB: My first introduction was music. My mom had jazz, old R&B, classical, rock, and folk albums, and in grade school, I explored hip hop, heavy metal, and house music. At that time, rap and hip hop shared that relatable urban experience. There was pride in house music being from Chicago.

Public Enemy and Rage Against the Machine were two groups whose music and videos were full of hard-hitting lyrical and optical visuals discussing social and racial issues. I was drawn to the content at that young age, and I felt comfort, anger, and relatability in the music. The song “Fight the Power” by Public Enemy, and the film Do the Right Thing by Spike Lee brought these issues to a broader audience.

It taught me to ask questions, research issues, and explore different mediums to express myself. I needed to express what I was feeling to process the actions of white supremacy personally and how it affects our communities. It’s therapeutic to deal with the anger and pain and release that energy for well-being. How do I communicate that? Through art.

There is the cultural component of going back home to visit family and participating in ceremonies. There is a commitment to preparing for ceremonies and seasons. There are life lessons with struggles and preservation; harvesting medicines, finding that tree for sundance, hauling water for sweats. There are commonalities in communities and the messages others are expressing.

AL: What do you enjoy the most about creating the work you create?

DB: I remind myself to respect the process of creating by contextualizing the narrative, those involved, and the medium. Art is therapy. Art is expression. Art is a struggle. It’s about seeing an issue and processing the pain, the anger, and the happiness. White supremacy is unrelenting, and creating art weighs heavy on the heart, mind, and soul.

The subject I address — it comes out of love because you, someone you know, and your community are affected by it. I don’t create for enjoyment of self-serving greatness, but rather I think about how it can lend a hand and say, “I acknowledge the struggle and people love you.”

The process for me is about addressing racism and white supremacy in our communities while keeping sanity. If a piece can reach one person to let them know they are not alone, we attempt well-being together.

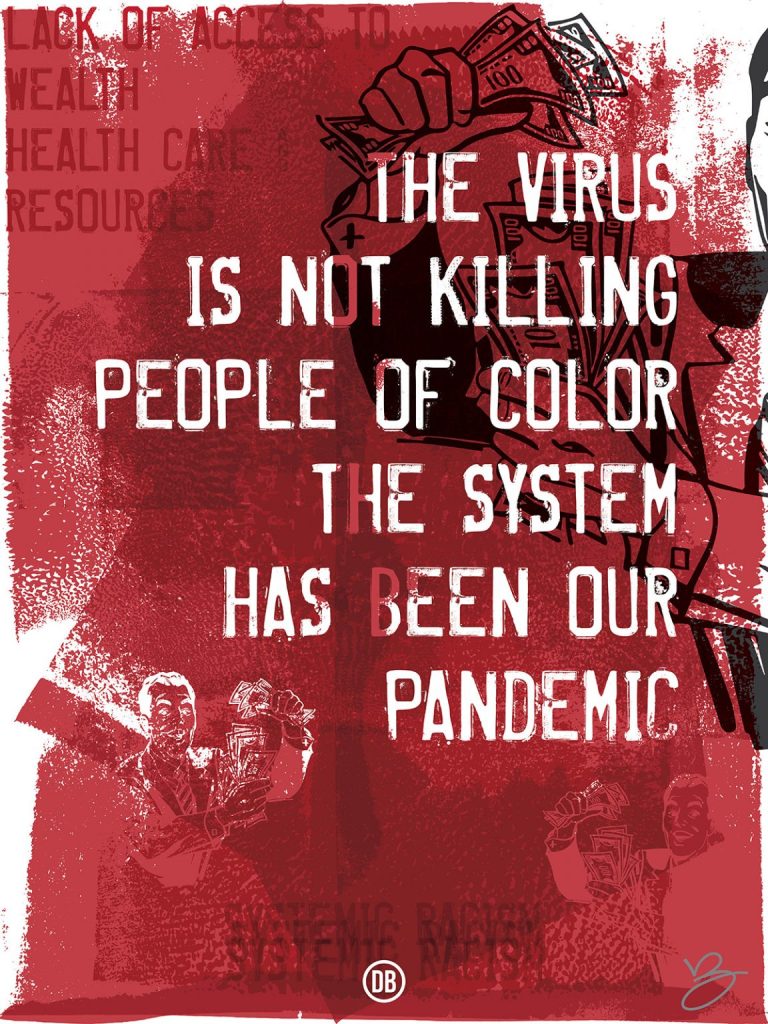

AL: I want to talk about a few newer pieces you shared on your social media back in 2020. I think what I really admire about the work you do is the intersectionality of some of the work. Could you talk a little about the two pieces you created below?

DB: It’s therapeutic how we process what we see and what we’re experiencing. How we can support our communities and reach out to say you are not alone. What I can do to provide space for someone we know who is directly affected by these white supremacist actions. If you are a part of the Chicago community, you know someone. It is hard not to know someone who was that person or the family or friend of that person.

These injustices and violence against Women, BIPOC, and LGTQIA+ communities that were exacerbated by the pandemic were new to many people. We knew many people who were shocked, afraid, and confused for the first time because they did not have the experiences in this city to realize our attachments to all these issues. They barely know one person from our communities, and even then, it’s superficial.

They don’t see what we go through, and they don’t see us as human beings or a part of their society. They don’t understand who we are, and they don’t see us for who we are. They don’t acknowledge or take the time to learn about these issues every day. But that’s colonization and capitalism — not caring for anyone but yourself.

I have no delusions that I can change the world or solve these issues with art, and I consider what role I play on the ground level, whether through direct action or by putting the message to a piece. I recognize that art can be a comforting voice for someone in the community or can create discussions with these newly “woke” people. These issues are continuous, and any action we participate in or art piece we create allows for moments of discussion, comfort, and sharing love within our community.

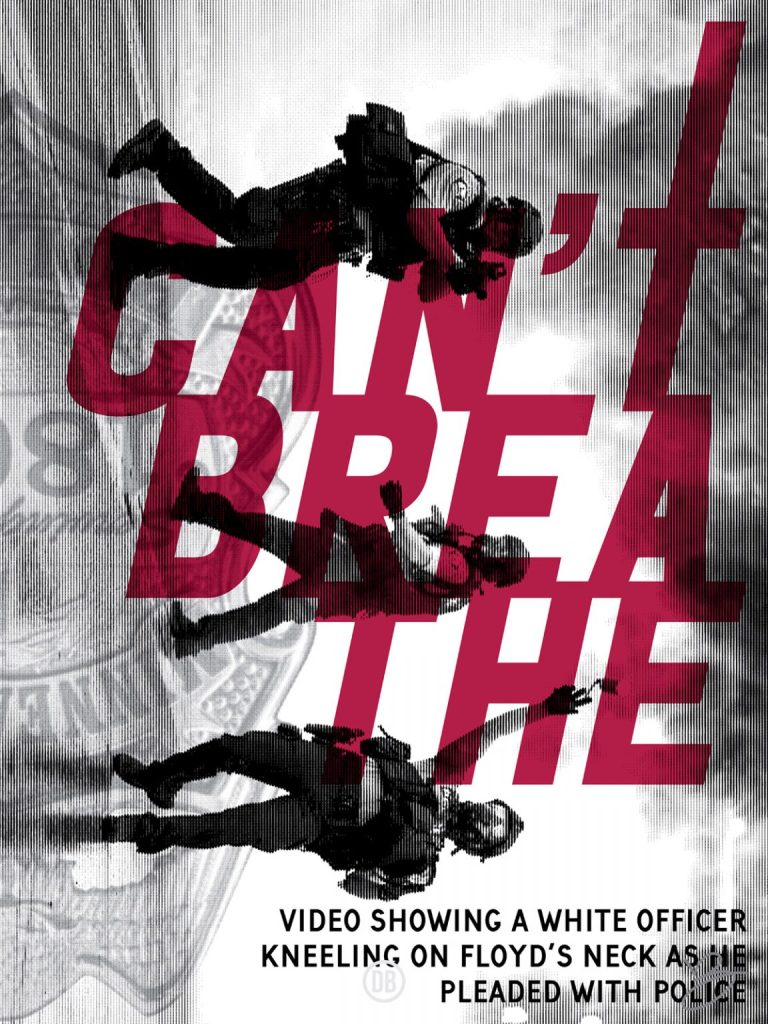

AL: Another very powerful piece having to do with current events was one focused on George Floyd. Why was this important for you to create?

DB: I created a piece regarding the racial violence inflicted on George Floyd by the Minneapolis Police Department entitled, “I Can’t Breathe.”

I had spent time in Minneapolis. I knew of the location of the murder of George Floyd. I knew of the places that actions were occurring. I knew of the segregation of the area and the violence by the police on Black Folx in that neighborhood. When you have attachments, when you have engagement with the land and defend the land and the people, it’s personal.

I thought of the pain that Black, Brown, and Indigenous Folx experience on reservations, in urban and rural areas, I thought of Rekia Boyd. I thought of Laquan McDonald. I thought of Breonna Taylor. I thought of Ahmaud Arbery. I thought of Eric Garner. I thought of Michael Brown. I thought of Tamir Rice. I thought of Philando Castille.

AL: I know some of the art you create explores some very heavy topics. Some have said certain topics are too dark or heavy to talk about with the youth even though these very youths are experiencing these very same issues. What are your thoughts on this?

DB: I recognize the art I create is heavy and touches on violent and harmful issues. Still, we have to remind ourselves that our youth are observant and experiencing these issues themselves. Growing up with music, friends, and family was a relief, and it was a community where I realized that other people are experiencing and talking about the same things. Our youth are not shielded from these issues, as they have family members affected by it. They see it in their feeds. Friends are talking about it. Adam Toledo could have been most of the people I knew growing up.

There are ways to approach subjects with others. But when people say it’s too dark or there are more important issues, it’s a dismissive excuse to avoid exposing our racist and patriarchal demons. It doesn’t have to be at that exact moment, but these things need to be discussed for progress. If we don’t talk about this, we’re not helping kids to navigate this world full of white supremacy and colonization.

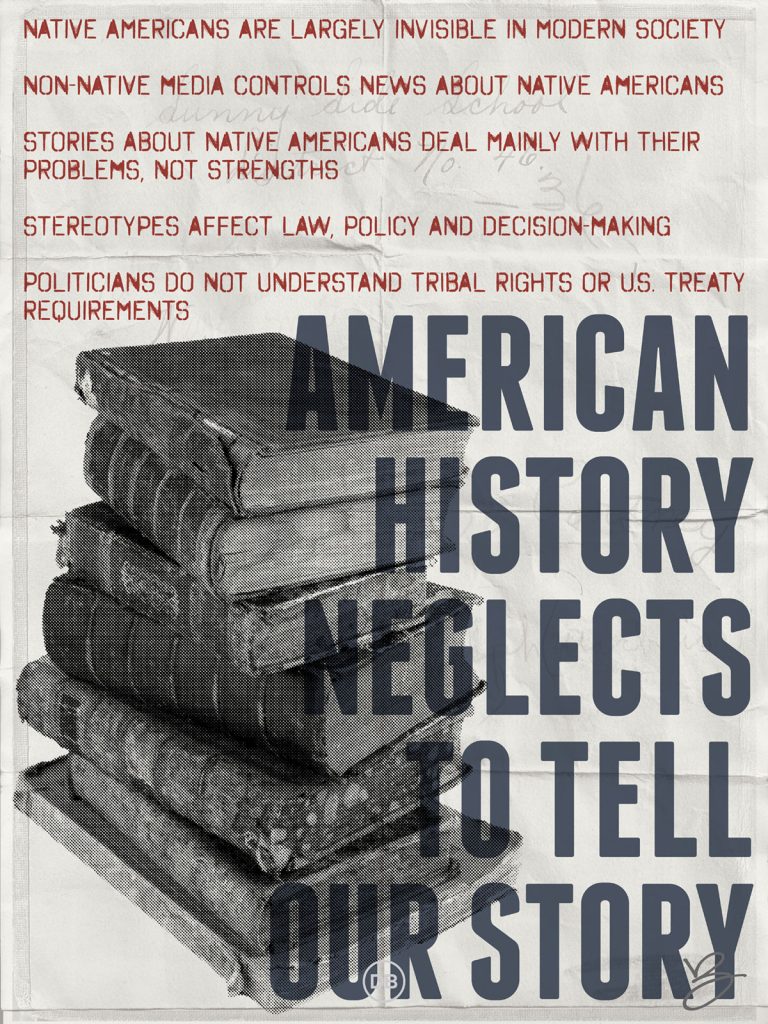

AL: One of the first art pieces of yours I came across was one with the text that said: “American History neglects to tell our story.” Do you think art can help with these historical silences? How?

DB: Being observant, documenting, and publishing our own experiences is how we can combat these inaccuracies. We need to give space for people to tell their own stories.

It doesn’t have to be visual art — it can be someone who writes essays and reports against these issues. It could be a teacher advocating for better books and media created by Black, Brown, and Indigenous Folx. White educators can relinquish their authority and allow community members to develop policies and curricula, remove racist prints, and introduce new resources for students.

There is a heavy responsibility when it comes to art. These issues of colonialism, capitalism, and white supremacy are invasive in our community, and they’ve been used to silence and divide communities of Black, Brown, and Indigenous Folks. Art can inspire change in curriculum and policies and address historical inaccuracies. History books do not serve the majority of the community, and instead they serve those who desire to retain power.

AL: Do you think it is the artist’s responsibility to address injustices in the world?

DB: If we are talking about art created by Black, Brown, and Indigenous Folx, there should be respect and humility regarding the role we play in society. It all comes down to intentions and how much colonization influences that mind. Artists shouldn’t put themselves in a situation to think that they are the saviors. It’s about community members as a whole. It’s about parents, teachers, aunties, uncles, cousins, brothers, sisters, and friends. It’s a community issue to have that responsibility, and it is a community that raises families.

Artists do have the tools to create. If an artist is ingrained in their community, that means they’re listening. A community has its resources of teachers, cooks, carpenters, laborers, gardeners, and librarians. Some of us can fill several roles, but the community is stronger when you have people with different resources and skill sets that can all come together and help each other out. Artists can be that resource and participate by creating art.

AL: If you had the opportunity to create an arts initiative or other non-profit, where would it be and what would its main premise be?

DB: That’s tough. I go back and forth with this. From personal experiences and those of friends and acquaintances, we see that many of these organizations are founded on white supremacy and capitalism. I see time and time again that white people and people you think are your community but have a colonized and capitalist mind run these organizations. They speak in a white tongue and advertise they are for a community, raise money for that community, are not from that community, and gatekeeping resources at the end of the day. No sustainable policies or resources are developed.

Their dominating egos and white savior mentality lead them to bounce around to other organizations. I’ve worked on community projects where we just fundraise on a small scale or pay out of pocket, where we find a way to get money for art and garden projects, for the panels, for the paints, for the soil, for the seeds, and plants. And it’s beautiful, and it just happens spontaneously. We find a way to make it happen with a dollar, but when corporations get thousands of dollars, barely a penny goes to the community.

AL: As a Native artist, what has been the most challenging?

DB: With the onslaught of capitalism and white supremacy, it’s a challenge to develop and grow your mind and heart with what space you can find. Being Black, Brown, and Indigenous, it’s even more challenging to find who you are and have to constantly assert and advocate for your identity.

I am very grateful that I could go back home between Chicago and my reservation in South Dakota and have those experiences. I think it’s very crucial to have those experiences at a young age.

I think about why I’m doing this. I’m not trying to take a space from anybody, and I’m not trying to be anything other than a community member. I remind myself by doing community work, by creating art, and by participating and showing love.

Does it make me a better person? No, but it reminds me what I value in life and how I learn and share knowledge. It’s my community, my friends, the garden, and art. It’s Chicago, my reservation, and a community of this whole continent. People with white supremacist views — even some Black, Brown, and Indigenous Folx — isolate people. They don’t respect that Indigeneity is land-based, and they don’t recognize that these borders and walls are constructed by white supremacy. They separate Folks from Canada, Mexico, or South America because the white man has taught them to divide, hoard resources, and seek praise.

I think it’s just trying to balance all these issues, finding out who you are, and finding out what love means to you. What’s challenging about Native art is counteracting ignorant stereotypes and blatant racism. The sad part is dealing with artists in your immediate community who jump in front of you to take any opportunity and not call out white supremacy in these institutions. They sell their art to the white gaze, and they’re just putting out work that perpetuates colonization. They don’t know who they are and don’t engage in Indigenous spaces. Everyone eats up the stoic Indian imagery, and they don’t want to see art that makes them confront their racism and white supremacy.

AL: What advice would you give individuals interested in becoming artists?

DB: Art should begin and end with developing and nurturing your heart and mind with humility. It’s about finding out who you are, where you come from, and how you figure into this world, your neighborhood, your community and other communities, your city, and your reservation (or homelands). How you engage with other Black, Brown, and Indigenous Folx is reflective of your upbringing and who you have grown into.

Just try to learn all you can and ask questions while respecting the time a person gives you to share that knowledge. Question the source of all sources that are through a white lens. Respect not only what you’re trying to convey but who you are and the process of that medium.

Realize you’re just one person, that the world is bigger than you, but you can still be a part of the world. It will take years of practice. Put yourself out there, as art reflects who you are. Take that chance, as that is the only way you can grow. You may develop wonderful relationships, and more importantly, with yourself.

It’s being self-reflective of your process and who you are, your development, and realizing that if you get to the point of progress, there’s always room to grow, and each year is self-reflective. Value your personal and artistic growth each year.

AL: I know you’ve been involved in quite a few Native planting projects and co-curating artwork at the First Nations Garden in Albany Park. You even contributed a piece titled “LAND BACK.” Tell me a little bit about these projects.

DB: There’s a 9-foot chain-link exterior fence at the First Nations Garden on Pulaski and Wilson. It’s visible from the streets, and we had the idea to put art up. The medium was 4’x8’ plywood with the artists painting on the panels.

We couldn’t go to most places during the first year of the pandemic, and there weren’t any art shows. The concept behind this was to create a collective art show in an open space and allow artists to safely create in the community. The outdoor gallery showcased people’s collaboration or connection to the space, and we asked each artist to create a piece based on their relationship to the land, what it means to them, and their experiences.

We had thirteen Black, Brown, and Indigenous artists come out for two months. We had tables spaced out, and it was an excellent time for people to get out of their homes, engage with the garden, and create. For me, it was good for the mind and soul to talk with someone new or someone I don’t usually see daily, especially in that time of the pandemic where we were losing connections with folks.

It also brings more identity to the garden. We have a teepee, a wigwam, a prairie area, and mounds and garden boxes full of native plants. All of this comes together to show resistance, love and happiness while providing a space with events for the community.

Regarding the Land Back piece, it’s a struggle to create art as messages become overused or a meme. But we didn’t have a garden sign, and I wanted to create that piece to give identity to the space and highlight the Land Back movement.

AL: What do you have coming up and what can our readers expect to see from you in the near future?

DB: Last year, I only posted a few pieces. I think my creative process at this moment has moved over to working in the garden, and that’s going to continue. We built a pergola structure with the roof being our water collection system. We grew a variety of plants and gathered more seeds for plants we didn’t. We were able to grow enough sage to culturally and ethically provide for the community. We want to possibly create a native nursery here. Maybe we’ll have the capacity for more plants and be able to do giveaways next spring. I’m also happy to work with friends and the community to develop their backyards to put in gardens, a community that is open spaces where nothing is being developed.

I love the community, and I love the people. There are challenges at the end of the day when you’re tired and sore, butI’m grateful and humble about what we’ve done. I do want to get back to making tangible art prints, multimedia paintings, murals, wheat pasting, stickers, and all that.

I’m not feeling sad that I’m not creating art at this moment because I know there will be a time when I will. What’s more important is the garden and what it represents, what it provides for people, what it means to the community, how it’s in defiance of white supremacy, and how it is reclaiming land back.

AL: Anything else you want to add?

DB: Breathe.

David Bernie and Analú María López recommend donating to either of the following organizations:

First Nations Garden

Chi-Nations Youth Council

About the author: Analú María López (Guachichil/Xi’úi) is the Ayer Librarian and Assistant Curator of American Indian and Indigenous Studies at the Newberry Library. As the Ayer Librarian and Assistant Curator, she helps steward the Indigenous studies collection while guiding library users through, connecting them with, and interpreting materials linked to the Indigenous Studies collection. She is interested in uplifting historically underrepresented Indigenous narratives dealing with identity, language, and decolonization. She is also passionate about intentional community collaborations for access to materials within colonial institutions, and the preservation, revitalization, and instruction of Indigenous languages. She holds a Master of Library and Information Sciences with a certificate in Archives and Cultural Heritage Resources and Services from Dominican University and a Bachelor of Arts in Photography with a minor in Latin-American Studies from Columbia College Chicago. Mrs. López began her career with the Newberry in 2004. After working for other libraries and museums in Chicago for 13 years, Mrs. López returned to the library in her current role in September 2017.