In Lars Von Trier’s The House that Jack Built (2018) Matt Dillon plays a serial killer named Jack. Jack is a failed architect and a sadistic loser whose violent appetites and delusions of grandeur merge into, what would become, the lifelong project of building his dream home. The home that Jack tries and fails to build becomes the one that he deserves: a haunted house. Rotting flesh litters the floors and numerous, nameless victims give out final death rattles. The film is long and the killings are painful to watch, as is Jack’s delight. Von Trier allows Jack to flourish in this sadistic, violent and selfish work, for a time. House feels like it should be included in the director’s “American Trilogy”, films which shine a light on our country’s casually unsettling brutality—aka what makes the “American Dream” possible for some—because Jack kills within a system that is built upon the violences he delights in. Violence here grows tight like mold in hallways and kitchens; in the most benign of places.

That idea of building what you deserve, out of the ravenous triangulation of violence, creation, destruction, and the evil that lurks within the most mundane of places, lies at the dark heart of Robert Kloss’ The Genocide House. Published through the Chicago-based Bridge Journal, Kloss’ book takes readers on a journey through time, violence, sex, and degradation amidst the death rattles of the American empire.

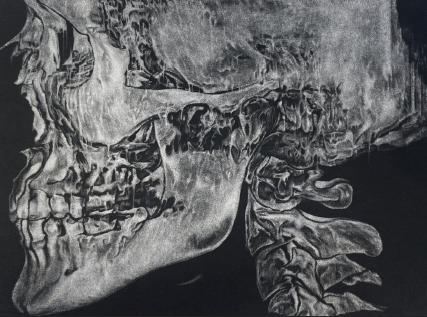

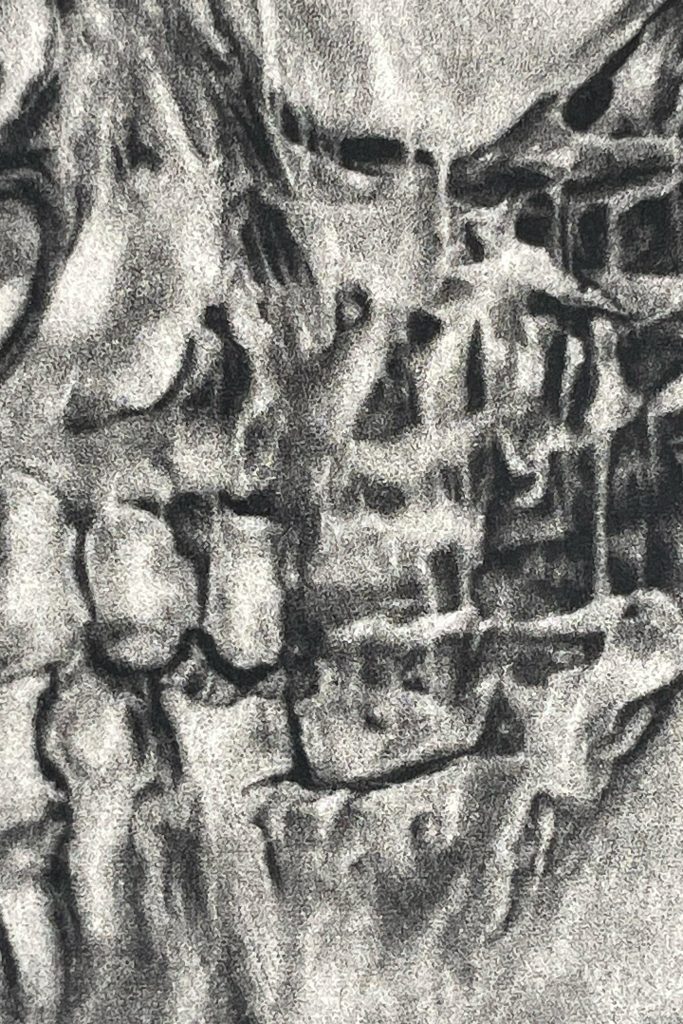

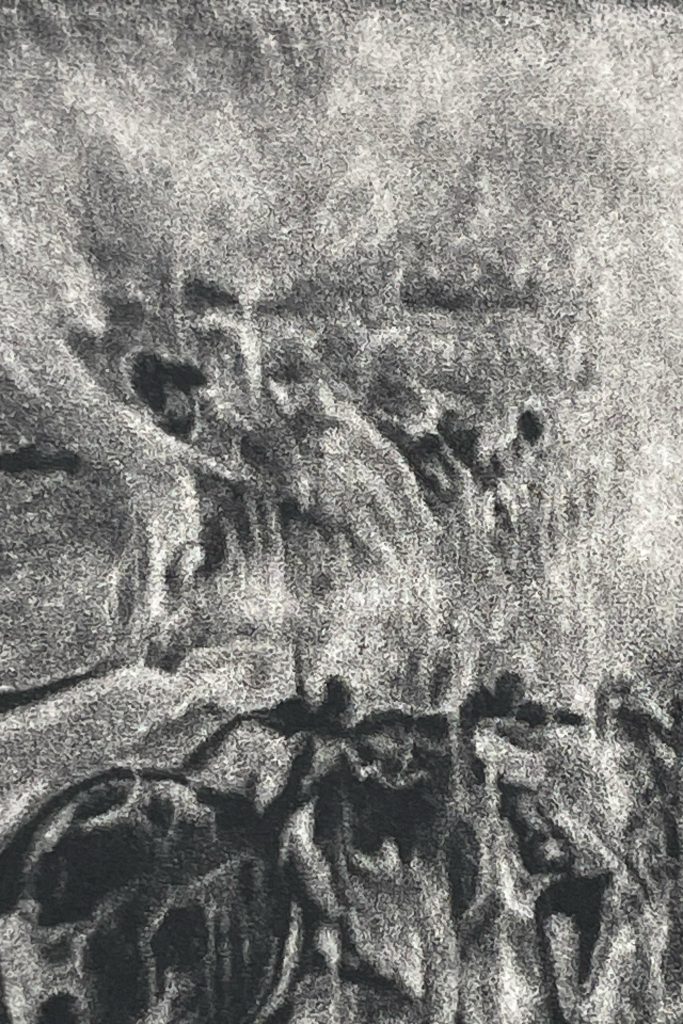

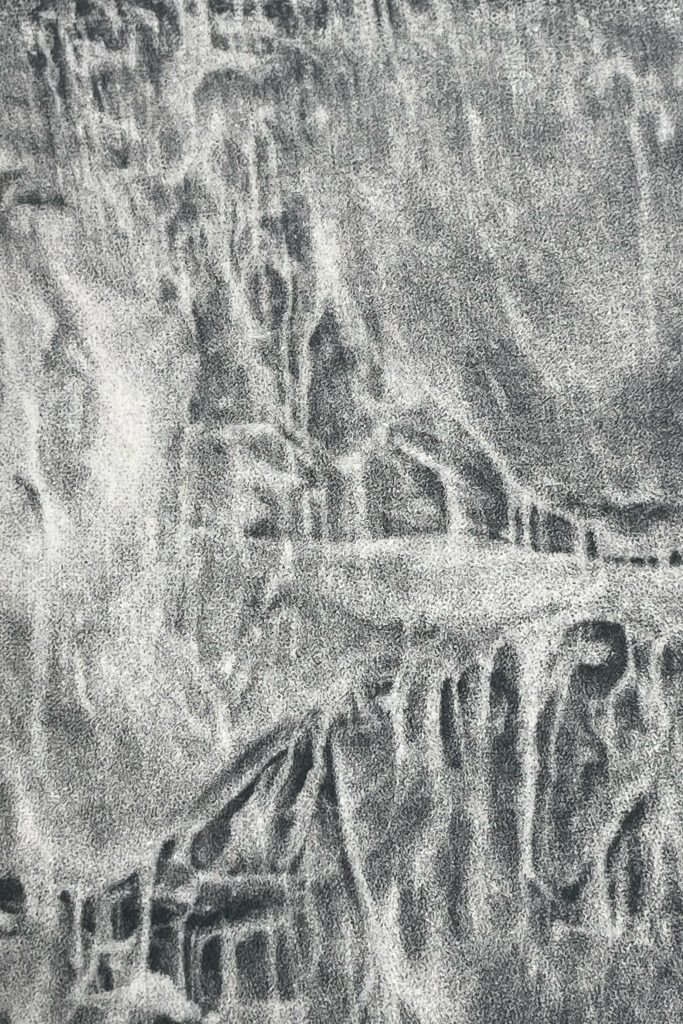

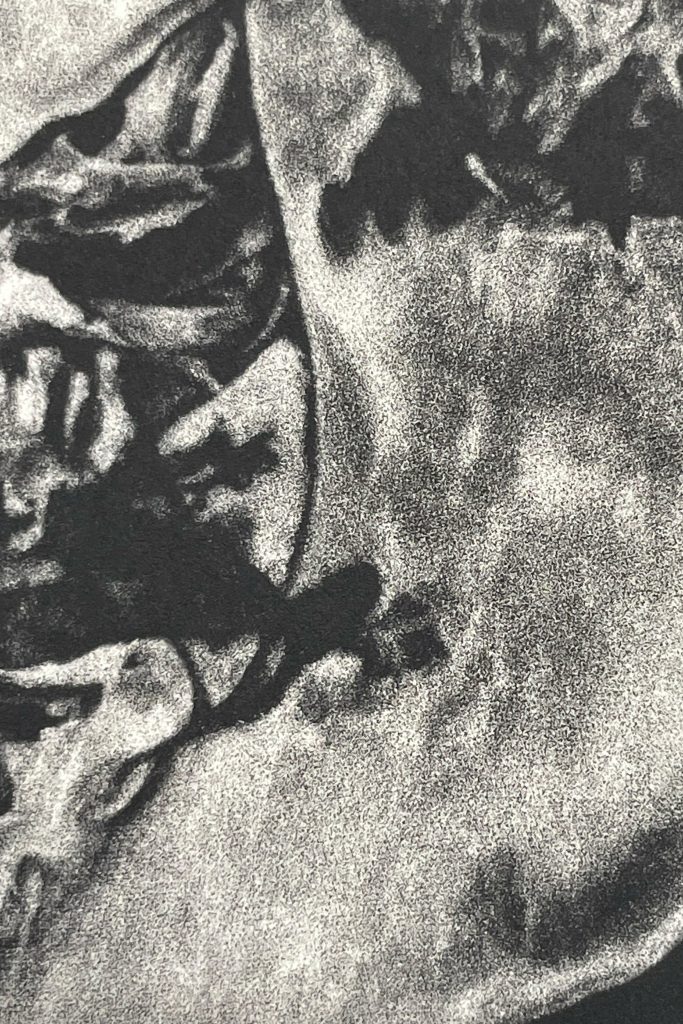

Notes on production: In the mezzotint printmaking process, a copper plate is first prepared with a semicircular, toothed chisel to hold a field of ink. The image is developed by scraping and burnishing into the surface of the plate, so that areas may express a range of tones. In this sequence of nine state impressions, the plate is further scraped down between printing, resulting in a thinning and softening of the tonal image. This gradual wearing down of the material by handheld tools alongside the expected wear and degradation of a mezzotint plate printed many times over yields atmospheric, abstract passages. This piece addresses the physical lifespan of the medium itself as well as the impermanence of the human body. All images by Devon Stackonis. All images courtesy Bridge Books.

The book opens on a section titled “1675-1678” that centers upon a pivotal incident in the United States’ history known as Pometacom’s Rebellion or King Philip’s War. Historians commonly trace the catalyst of the war as the murder of three of Pometacom’s warriors by the Plymouth Colony, though analyses of the conflict also note that these murders were precipitated by decades of colonial encroachment upon Indigenous land, culture, and resources. This rebellion is a key point in colonial history as it is one of the first battles in which the U.S. began to separate itself from Great Britain. Through violence and land, the U.S. began to form an image of itself as an entity distinct from Europe, one with a character, a soul all its own.

Our narrator, whom early on we learn is named Clara, is the wife of a powerful man in the U.S.’ own early colonies. The husband sees this country as one filled with devils and heathens and plays a critical role in the colonies’ brutal attacks against the nearby Indigenous tribes. The Christianity he espouses is built upon unwanted subjugation—serving girls and a young male assistant disappear into his study for hours at a time for some amalgamation of sex, of rape, of violence. Yet, Clara begins to crave his brutality—sex, power, and violence being forever messily intertwined. We begin to see a messy complicity illuminated through her physical desire, which expands to include her role in the colony’s corruption.

Early on we’re taken out of time. The husband calls servants, his assistant, and Clara to his chambers through an “infernal device” whose “tendrils of wires [. . .] line the walls” (14). Electricity here works as a shorthand for a sort of all-knowing authority; whether the panopticon is built upon the law, the husband, or the violent impulses that live within you, every move you make is there for power’s appraisal, consumption, and ultimate satisfaction.

Soon the nearby tribes, led by Pometacom, launch a counter-attack on Clara’s colony and take her hostage. Clara joins the tribe and the raid’s hostages on a winding journey through the wilderness, where we’re taken to an isolated stone gable manor that also stands out of time. In the manor,

“screens of glass—hang upon the walls like—silk draperies or—portraits—These are not mirrors—I think—squinting for my reflection—Curious fingers click the screens—hollow echo—Some lie mute—darkened—Other screens—flicker—glow—Yes these screens writhe with motion—Images—shimmering” (41).

Upon closer inspection of the screens, Clara and Pometacom (whom Clara refers to as Philip) see a man enter the frame, “I am become—his lips might say—destroyer—worlds” (41). The screens then shows

“a cloud swelling—a terrible wind—trees—houses—swept away—The image is repeated—Now—bodies of ash—bodies—against walls—shadows of bodies—I shake my head—I’ve never seen anything like this before—Yet—I know—Yet the images follow—my thoughts—“ (42).

I understand these screens to be televisions and the reference to the man speaking an approximation of the phrase “Now I am become Death, destroyer of worlds” a gesture to J. Robert Oppenheimer’s 1965 interview with CBS News. In that interview, Oppenheimer defended the nation’s use of the atomic bomb, the consequences of which are the bodies of ash Clara sees upon the manor’s screens. Kloss positions Oppenheimer as an architect of the American project, versions of which we see in the book’s ensuing sections which take place during the tail end of the Gilded Age, WWI, and the Vietnam and Cold Wars; with interludes involving the alternate histories of the moon landing and Richard Nixon’s resignation.

Versions of Clara and Robert flit throughout each section like ghosts; they are shadows that always seem to find their hosts. Clara might be a kept colonial wife, or a woman in the Chicago stockyards, or a masochistic war veteran, or Robert’s accomplice and spiritual mistress, but she is always drawn to the violences that live outside herself; the breaks and cracks that mirror the ruptures that exist within. There are also shades of Robert within Clara’s colonial husband who with his “infernal device” knows more than he was ever meant to know. This is not to argue that the same characters appear throughout the book, but rather that Kloss renders Genocide with a wraith-like texture. The book’s slippery words bend and mirror one another; they force you to question if you’ve met this character before.

The narrative voice begins through Clara’s point of view; the syntax is panting and fragmented. Sentences are rendered in a dreamy staccato, interrupted observations separated by em and en dashes. We stay with this voice throughout the novel with words pulled through your teeth like taffy. Sentences take time to process by virtue of both content and form. This is a book drenched in blood, guts, and viscera. The act of reading is then appropriately transformed into a struggle, of gasps and doubling back; of not quite believing where this story might take you. There’s a faint echo of Mark Danieleswski’s House of Leaves throughout Genocide House, another work built upon the architecture of haunted houses and the repetition of memory. Or maybe it is the shared sense of growing unease within the two works, the ghosts that emerge from just under the floorboards and linen closets, those howls that light television screens.

In the final section, a postscript titled “BASEMENT TAPES 010374-010383” we’re treated to text taken from the transcripts of home videos shot by Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, the Columbine school shooters. The two boys talk about the people they hate and plan to target in the shooting. They talk about being dead before prom, they talk about wanting to die and loving the feeling, they talk about everything, but what transforms them into the “American Nightmare” of television broadcasts. Genocide’s narrative voice then tells us both Harris and Klebold step beyond the knowable. Yet I think it is this idea, the impossibility of knowing why, that girds all of the novel’s many violences. We live in a world where brutality is often committed for a bottom line or for the sickening fact that it simply can, as the gulf between us widens ever deeper.

The book’s epigraph—“At the Genocide house / The killer is close / You can smell it”—are lyrics from musician and artist Alan Vega’s final album IT (2017). The album consists of field recordings from 2010-2016 Vega took around his gentrifying Manhattan neighborhood shortly before his death that same year. In a review of the album on The Quietus, the reviewer recollects the last time they spoke to Vega. During that conversation, Vega stated “People getting wealthy on fucking Vietnam. The same people buying all the art. It’s blood money baby, it’s all about blood money.”

It is difficult not to draw parallels between America’s financial and military involvement in Vietnam—whether it’s the money made by Monsanto and Dow Chemical for the creation and production of Agent Orange (carrier of one of the deadliest neurotoxins in existence) called a “tactical herbicide” by the American military or Texas contractor and friend of President Lyndon B. Johnson, Brown & Root’s $380 million dollar contracts to build up infrastructure in South Vietnam for the use of the U.S. Navy during the 1960s—to our current financial and military involvement in Gaza. Consider these facts:

1) The political lobby AIPAC, short for the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, has spent over 100 million dollars this year in American elections with the intent to oust progressive political candidates who they deem “not sufficiently supportive of Israel.”

2) In the case levied against Israel by the country of South Africa in the United Nations’ International Court of Justice, South Africa cites the definition of genocide laid out in the UN’s Genocide Convention to assert that Israel’s actions towards Palestine and the people of Gaza are genocidal in nature as they are committed with the intent:

3) The Council on Foreign Relations reports that today nearly all U.S. aid goes to support Israel’s military, with a “provisional memorandum of understanding” providing Israel with $3.8 billion per year through 2028. Since October 7th, 2023, the U.S. has already promised at least $12.5 billion in military aid to Israel.

4) The Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, a well-heeled think tank that began through donations from the Koch Foundation and George Soros’ Open Society Foundation and has alternately been accused of isolationism and anti-Semitism by at least one Republican senator, has begun tracking incidents where Israel used U.S. weapons in potential war crimes and human rights violations. The Institute admits in their reporting that confirming these accounts is difficult as

“Israel restricts U.N. and NGO access to Gaza and doesn’t cooperate with investigations into misuse of U.S.-supplied arms. Members of the press are routinely denied access or attacked: Since October 2023, 116 journalists and media workers have been killed by Israeli airstrikes or sniper fire in Gaza, representing 86 percent of all those killed worldwide.”

5) According to the U.S. Campaign for Palestinian Rights, the approximately $40,705,222 collected from Chicago taxpayers by the federal government (estimated by multiplying the American taxpayer’s average contribution by Chicago’s population), and currently sent to the Israeli military could instead be used to provide healthcare to over 14,000 children.

6) Blood money, besides being shorthand for money gained through ill-gotten, violent means, is a descriptor of an ancient Germanic tradition in which an offender would pay a fine to their victim or victim’s family, the amount of the fine commensurate with the severity of their crime. In contrast, traditional Jewish law forbids blood money. Such a custom is forbidden because under Jewish law a person’s life belongs only to God. Under Jewish law the taking of a life is the most grievous of violations; it is a violence that can never be erased.

This I think is the lesson of Kloss’ Genocide House. Blood money surrounds us, violence and death burn our screens. Look closely in the mirror, are you sure you’re not holding the knife, the gun, the noose? Are you sure you aren’t the star of your own killing floor? Look at what you, what we’ve, built. Don’t you dare look away.

You can check out Kloss’ book here.

About the author: Annette LePique’s writing has appeared in Momus, Hyperallergic, Chicago Reader, Eaten Magazine, New Art Examiner, NewCity, and other publications. She received master’s degrees from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the University of Chicago, and is a 2023 recipient of the Rabkin Prize for art journalism.