Para leer en Español, presione aquí.

This essay is published as part of Sixty’s Midwest Arts Writers Fellowship, an opportunity for writers to develop, refine, and publish writings on topics that are relevant to Indigenous, trans, queer, diasporic, and/or disabled artists and arts workers in our region.

When I moved to America, the sights and sounds that had underpinned my life in Indonesia were gone, and as I married and had a child in the US—it became increasingly unlikely that those would be my daily surroundings ever again. I spoke English fluently, but I was learning a completely new language, a completely new aesthetic and spiritual lexicography. The dictionary of visual cues that fed me and communicated to me were gone. I had to start again.

2010’s Brooklyn normcore fashion left me feeling clownish and overdressed in the clothes I had brought with me. How was I supposed to be happy in this place?

Although I am not a practicing Muslim, I remember playing the Islamic call to prayer on my laptop over and over again as I curled up in the top bunk of my New Jersey dorm room and wept. I had never experienced a day where the hours were not marked by the mosque’s call to prayer, five times a day. Coming from a land of bright sarongs and batik patterns, 2010’s Brooklyn normcore fashion left me feeling clownish and overdressed in the clothes I had brought with me. How was I supposed to be happy in this place? All the visual, auditory, relational, and spiritual markers of my life in Indonesia I equated with contentment were gone.

. . .

The queer, Argentine Theologian Marcella Althaus-Reid wrote, “Only in the longing for a world of economic and sexual justice together […] can the encounter with the divine take place. But this is an encounter to be found at the crossroads of desire […] This is an encounter with indecency, and with the indecency of God and Christianity.” For the migrant, there is often a constant twinge of shame leveled against you, because you left, but you also never completely assimilate. There is a drive to prove your decency. In the following conversations with two Indianapolis artists about their migration, artistic, and spiritual journeys, Althaus-Reid’s theology of indecency becomes central. In her work she makes the case that theology is written by the lived sensual experiences of the bodies of marginalized people. Visual art is as much public theology as any academic article, and in the art of artists: Samuel Penaloza, Maurice Broaddus, and myself, a theology of the fallible human body is still central.

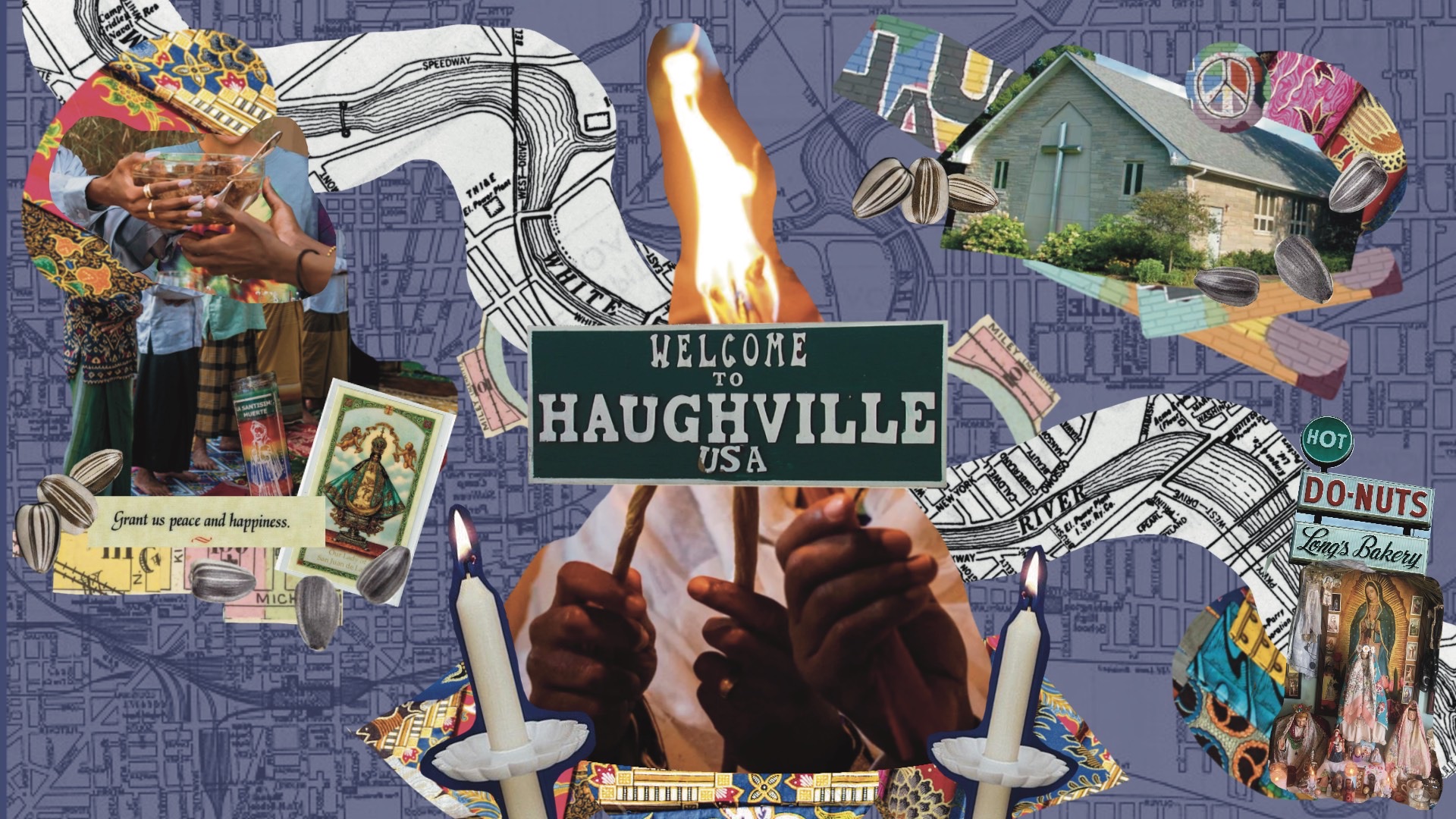

In my conversations with first generation artists here in Indianapolis’ Westside, it’s apparent that while all artists build their own visual dictionary within their body of work, for migrants and children of migrants, the process is uniquely isolating. This article is a tribute to Haughville, the small West Indianapolis neighborhood that has become my teacher and my church. My poetry of place is interspersed with the voices of several artists who are part of this sacred congregation we call an arts scene.

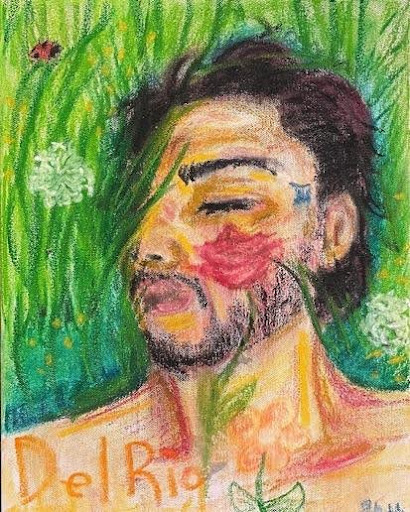

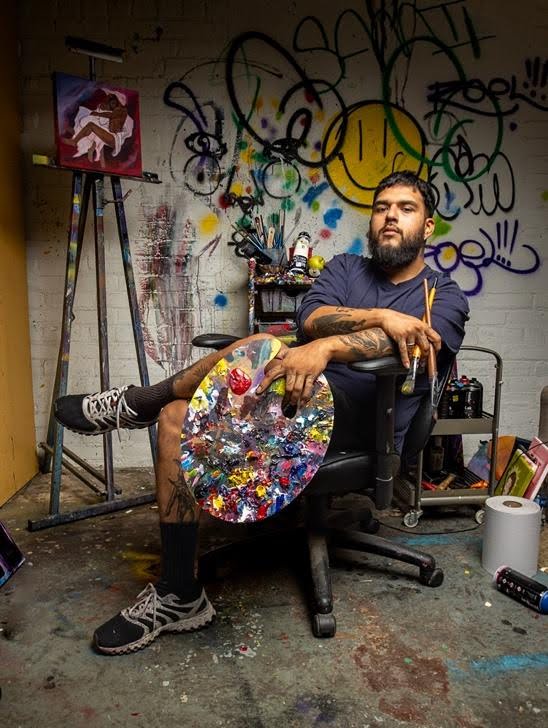

Samuel Penaloza is a Mexican-American painter living in Haughville, and one of those artists for whom creating is a compulsion that seems almost painful in its drive. His mother was brought to the US as a child, had a difficult upbringing as the main caretaker and laborer for her family, but does not speak English. Sam describes his family existence as a “Mexican bubble,” a life lived in America but enshrined in Mexican language, food, tradition, community, and faith.

He talks about the God of his childhood—a God of constant surveillance but also a Catholic God that was specifically Mexican—not American. A God that needed to be fed by sacrifice.

His acrylic pieces often have nude female figures in contorted or bound positions, struggling to free themselves. He talks about the God of his childhood—a God of constant surveillance but also a Catholic God that was specifically Mexican—not American. A God that needed to be fed by sacrifice.

“My mother had altars and pictures of the Virgen de Guadalupe everywhere,” he says. “God was always watching.” As we talked, he pulled from his wallet a saint card of San Juan de Los Lagos to tell me a story of pilgrimage and sacrifice. “I had really long hair when I was ten,” he tells me. Then his brother got sick. And his mother told him he would need to cut his hair as a gift to the Virgen so his brother would be cured. The whole family took a trip to Mexico, where they all walked on their knees up the stone-floored aisle of a small church. When they reached the altar, their skin was ripped and bleeding. His mother and aunt cut his hair and left it at the church in an upstairs reliquary full of other gifts from the faithful.

“Did your brother get better?” I asked. “Actually yeah, he did,” Samuel smiles ruefully, “but when I went back to that church the next time my hair was gone.”

There is no way to describe the aesthetic language of Penaloza’s paintings except Catholic. There is a distinctly religious overtone to the work, something evocative of folk saints and household altars. There is also something distinctly Queer in his aesthetic. Queer in the way that theologians like Althaus-Reid uses the term—as an aesthetic term (v) that means to “make strange, to frustrate, to counteract, to delegitimize, to camp up heteronormative knowledges and institutions”. We often use the term queer to mean an identity, but in its verb form it describes an active practice of issuing a challenge to hetero-aesthetic norms.

We often use the term queer to mean an identity, but in its verb form it describes an active practice of issuing a challenge to hetero-aesthetic norms.

I bring up a specific painting of Sam’s, one that he created years ago sitting on my living room floor during a dark period where we were both completely broke, nothing guiding us but dollar store paints and a gnawing drive to make art. “I remember a sketch you did of me a long time ago, started with me laying on the couch then you started adding things: a giant foot and a giant leg, and then you erased some of my hair, and eventually the figure that was me started flowing off the couch and you did more bodies on top so there were three female figures in different dimensions.” He nods thoughtfully and says simply, “Being self-taught, I don’t always know how to get it right, so I just have to make it up as I go.” Althaus-Reid would call this doing theology.

I observe out loud to him that he often portrays his nude male figures in curled up poses in the vanishing point of the composition while his female figures tend to take up space. He says, “those figures, when it’s a male it does happen through insecurity. Being afraid. Kind of in that fetal position like a child you know.” So many of his paintings have eyes prominently worked into the composition, often the human figures being observed by these giant eyes seem in pain, and almost as a call back to that stone floor and his bleeding ten-year-old knees he tells me, “it’s hard to feel inspired without the pain, but I want something new now”.

. . .

When I stepped off the plane at the International Arrivals terminal in Newark, New Jersey I was 17, alone, and did not yet know that my two greatest assets, as I embarked on a new life in the United States, would be my absolute naivete about how bad things could get, and my Animist faith. I matriculated at a small, somewhat unpleasant college in North Jersey, and tried my best to be happy. There were other things I did too—I went to class, got a teaching fellowship, had a baby, got married, and earned a masters’ degree while breastfeeding my brains out (and graduated with honors!), followed by a decision to move to Indianapolis. Ultimately my main preoccupation was trying to be happy, and I found it exceedingly difficult-in part due to the aesthetic language around me.

We take in words and translate them to an internal visual image. The word “tree” conjures a brown and green branchy thing. We also take visuals and translate them into emotions or instructions. The sight of mold on food warns us not to partake. As a migrant from a tropical island, nothing was ever gray unless it was dead or diseased. What then was I supposed to make of the six months a year that the sky and air seems perpetually gray in Indianapolis?

. . .

Maurice Broaddus has no trouble taking the visual and translating it as words on the page. When I walk through the heavy wooden double doors of the building where we are meeting for our interview, he greets me with, “You always have the best outfits! I hope you don’t mind but I took the outfit you were wearing the last time I saw you and made it the science officers’ uniform in my new book.” The outfit he was referring to, worn to a gala we both attended, was a plunging green velour dress open to the navel and slit up to the thigh paired with a vintage fur stole and sky-high black stilettos. I followed him into his office silently questioning the job description of these science officers—did it include field work?

Photo courtesy of Maurice Broaddus.

Broaddus is a writer most known for his afro-futurist fiction novels including his upcoming graphic novel licensed by the “Black Panther” franchise. He grew up first in England then on the West Side of Indianapolis with a Jamaican mother and Black American father who had met during his father’s army posting abroad. We dive right into the conversation with a discussion about Broaddus’ mother and his childhood church, a predominantly white congregation on the West side of Indianapolis.

He describes a childhood that resonates deeply with me because we both had parents who had migrated to England before continuing the diaspora elsewhere. He tells me about a family dinner where his mother made everyone watch the hours-long wedding of princess Diana and kept collectible items featuring British images. He says his mother did not feel excluded from British society, despite the class divisions, she felt she had access to it in a way that her American husband and son did not. America was a downgrade. While both his parents were of African descent, “we were always ‘you people’ to my mother,” he says speaking about his Father and himself. To his mother, Black American was an ethnic designation devoid of culture and roots. “Interestingly, my sisters were included as Jamaican to my mother, just not the boys,” he adds.

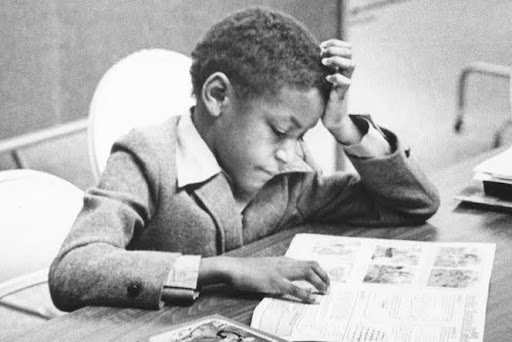

It wasn’t just at his family dinner table. Maurice tells me about the church he attended. His mother had asked the (white) neighbors to take the children to church, and so they ended up at a Brethren Church where the Broaddus kids were the only Black children in the congregation. “Racism was codified into their theology” he says, “there was a lot of the mark of Cain and the curse of Ham stuff going on.” He describes how apparent that was in one specific photograph of his youth group. A flock of white children and then Maurice, tucked away into a literal corner conspicuous both because of his race, but also because of the way he is positioned in the spatial composition of the image.

Words have always been his tool to do justice in the world, to live his faith.

But for all this racism in his childhood church Maurice is clear about his faith, “Love God and love people,” he says. Another lesson he carries with him is central to many Christian theologies—“The Word was with God and the Word was God.” If there is a spare moment in his day, Maurice is writing. In between meetings, or during TV commercials—words are in his DNA. He tells me the story of meeting his wife Sally. They originally met as teens in that Brethren church of his childhood. And according to Maurice, Sally’s family was the wrong kind of white. “They [the church] treated her family worse than they did the Black kids,” he says. That stuck with him. And years later, when Maurice and Sally crossed paths again in college, he had a long apology speech prepared—one he had been composing for all the intervening years hoping he would have the opportunity to repair the hurt caused. Words have always been his tool to do justice in the world, to live his faith.

His book Buffalo Soldier, a slim volume, keeps coming up in our conversation. It is not the best known of his work nor the longest, but it’s the one he describes as “a love letter to my mother.” It is an alt history story, in which Jamaica is a superpower (but not a colonizing force), and centers a young boy named Lij who is being hunted by both the Jamaican government and the lands through which he and his reluctant guardian Desmond live on. Lij is a migrant and extraordinary, but that extraordinariness makes him othered. Maurice says, “One of the things people notice about my work is identity and community [which] are two big threads of my work, but I operate out of a space of feeling isolated and having no community.” In many ways he has never left the youth group corner, but his work does much to soothe those readers who have experienced being “you people.”

. . .

The writer Rebecca Solnit writes in her book Wanderlust: a History of Walking, “Pilgrimage is premised on the idea that the sacred is not entirely immaterial, but that there is a geography of spiritual power. Pilgrimage walks a delicate line between the spiritual and the material in its emphasis on the story, and its setting though the search is for spirituality,” what is migration then, but a pilgrimage couched in political terms, packaged in layers and layers of paperwork, interviews, application fees, and the interminable waiting.

I started writing as a teenager, first as a way to process the world—I am autistic and human behavior was so puzzling to me. I read and wrote voraciously as a place where I could unmask and inhabit other bodies unencumbered by mixed-race parenthood and theological questions of salvation. I am a migrant mother who lives in an Indianapolis neighborhood where people joke the homicide rate is measured by the square foot, but this neighborhood, its streets, its river, and its people are sacred geography to me.

. . .

THIS IS DOGTOWN

By Nasreen Khan

One day I bought a house on my lunch break.

It’s a 1930’s bungalow in “Clark’s addition to Haughville” which is really just the black part of Haughville before you get to what used to be the Slovenian part of Haughville, which is not the Mexican part of Haughville. It’s not on the map like Stringtown or the bougie River West the new developers want to call it.

Walking home from the library, last summer, pushing the stroller past the corner of Belmont and Michigan where a girl was killed in a drive-by one night after she got off her shift there is a mural shrine to Courtney Paige who was a dancer at Patty’s show club.

That summer my son was still in diapers, the air hot as hell, and muggy like menudo on Sunday morning. He said shh mama that dog is sleeping, and stuck a chubby hand out the stroller shade and into the sun.

And it’s true that dog was sleeping in the grass between the sidewalk and the road – Right across from the pink and blue letters remembering Courtney Paige. Courtney Paige, born in the same year as me, on the same day as me. I don’t know what day she died, so all I know is that her death shrine lists my birthday. I don’t know what day she died, but I know her little girl, who’s a little older than my son, likes to eat kraft cheese singles between slices of wonder bread while she rides her bike down the sidewalk between her house and mine, and that when I moved here her aunt said we’ve never had no trouble living here and Courtney’s little girl looked in my eyes and said except for when my mama passed.

And on the sidewalk across from Courtney Paige like he was laying at her feet – it’s true that a dog was sleeping in the grass between the sidewalk and the road – a half grown husky with its head on its paws sleeping with ants crawling out of empty eye sockets, half covered in sweet fuzzy eyelashes, fat grubs falling out of his ears.

After I took my baby home for his nap and read him stories and kissed his brown cheeks and thought about getting a shovel myself, I called a whole bunch of numbers of places with names that seemed like they were supposed to help.

But there isn’t an office, I guess, whose job it is to come and bury dead dogs on the Westside.

. . .

I make part of my income as a visual artist. I began my creative life as a writer but discovered that I had a passion for visual art and that it was an easier way to make a living compared to writing. Recently my visual projects have focused on my past—my childhood in Senegal and Indonesia. I want to write about my present—here in Indianapolis. I care deeply about this place. But violence and faith are intertwined here on the Westside. The neighborhood has at least 20 churches, everything from AME to Hagia Sofia Greek Orthodox to Holy Trinity founded by Slovenian immigrants in 1906, and that’s only counting what shows up on google maps—not the tent revivals, the living-room Pentecostal fellowships, or Orisha dances. Faith remains important here. Spirituality intersects with the other issues of the Westside: immigration, race, gentrification, poverty, environmental pollution. Faith is also central to the power structures in the Midwest and Indiana specifically—everything from KKK history to current legislation around library books.

Additionally, many artists in the burgeoning Indianapolis art scene come from migrant backgrounds where faith holds a significant weight. As church attendance declines generation by generation it’s easy to dismiss religion as no longer relevant. But all of us, especially artists, are still influenced by religious history. I see this in my artist friends and neighbors who hide their queerness from family/communities, and when I am rejected by galleries because my nude paintings are deemed lewd. Religious shame and guilt, as well as revival, are currently very relevant to the social tides of the Midwest and to the migrant experience.

Growing up, whiteness and heteronormativity was the passport to privilege. As a biracial girl, I didn’t quite know how to define myself. That lingering sense of otherness persisted. I became fascinated with the margins. My graduate research looked at the spirituality in trans sex workers of Asian and African diasporic literature. The Mennonite-influenced faith tradition that I grew up in placed much emphasis on gendered expressions of devotion. I find myself exploring the racialized, radicalized, feminine appetites that my early faith asked me to restrain. Haughville, and its people, has become a place where I’ve pursued an exploration of those appetites without shame, an appetite for transformation, for pleasure, for pain, and for revulsion—writing an indecent theology of my own.

. . .

Looking for a decent taco,

I wander into Guanajuato – Tripe maybe – or chicharon stewed in green sauce

Is that called guisado? I don’t know I don’t speak Spanish

I just live in a Spanish ghetto, black ghetto, white ghetto, not really a ghetto at all, just a group of houses with poor people living inside. I’m maybe the poorest, except Nyesha next door: good hair, 19 with a 4yr old and a Dominican boyfriend

who blocks her car in so she can’t go out but

I know people think I’m stuck up, look at that morena with the old white husband.

When I push the stroller to the park I hear them call me, come here chica! Oh what’s the matter?

you only like white dick?

Damn girl I’ll put a black baby in your belly to go with that white one.

What is it they think when they offer to occupy my womb, the space between my thighs for an afternoon. Do they think if they put flesh inside me to stay for nine months that they own a part of my belly,

or my soul? Like a timeshare condo

or like the houses here with rent to own signs in the yards.

And maybe all that is on my mind when I walk past the

white junkies by the shopping carts, dope sick all of them, and I almost give them

my 2 dollars

because I can’t stand to see anyone dope sick, never have. There is something

like clotted evil about

walking away, like eating sunflower seeds at a

slave auction

And maybe because I do walk away, it puts me in the mood for tripe and skin, even lengua is

too clean for what I’m feeling.

I need to eat guts, and think about the pig they came from. Did it still struggle on the hook while they pulled its innards out into a steaming bucket of offal and shit?

The man ahead of me in line kisses his lips at me and buys my tripe.

When I sit down with it, he frowns and cocks his head like

I’m supposed to be so grateful, I’ll suck his dick right there

between the stacks of yerba buena tea and votive candles so I take my

paper plate and wander down the candle aisle looking for

a better Virgin

candle. I bought one when I was trying to have a baby.

I kept it lit while we fucked endless babymaking rounds. But the paper cover is getting faded and I left the window open when it rained so

Guadalupe’s robes are wrinkled now, the color of a ball sack pulled up tight

right before orgasm.

If the Virgin Mary lived in Haughville would those men outside the dollar general offer to put a baby in her? Would they mind getting god’s sloppy seconds?

But all that’s useless here, there are no blue candles to the Virgin Mary only

black ones for Santa Muerte,

La niña blanca,

skeletal patron saint of drug dealers and

whores.

I eat my guts and stare her down, a wall of black stretching

down the store, and

she grins at me from under her hood,

sexy girl,

her long tongue licks the bones where her lips should be. Points to the taco,

can I have a bite, she asks?

Nasreen Khan’s poem THIS IS DOGTOWN was originally published in The Indianapolis Anthology, edited by Norman Minnick and published by Belt Publishing.

* * *

This fellowship is made possible with support from Arts Midwest. Arts Midwest supports, informs, and celebrates Midwestern creativity. They build community and opportunity across Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, Wisconsin, the Native Nations that share this geography, and beyond. As one of six nonprofit United States Regional Arts Organizations, Arts Midwest works to strengthen local arts and culture efforts in partnership with the National Endowment for the Arts, state agencies, private funders, and many others. Learn more at artsmidwest.org.

About the Author: Nasreen Khan (she/her) is a writer, visual artist, teacher, and mother. She grew up in West Africa and Indonesia and has recently made a home in Indianapolis. Her teaching and artistic practices, rooted in questions of equity and earth-based spirituality, grapple with questions of belonging; celebrate cultural margins; and confront colonization, racism, and misogyny. @heyitsnasreen

About the Header Artist: darien hunter golston (as written; pronouns – he/him, ey/em or d) is an earthkeeper, domestic artist, full spectrum doula and sometimes writer living between Waawiyatanong and Zhigaagoong (Detroit & Chicago, respectively). d labors to create pockets where freedom, ease, pleasure, and play are possible for Black folk, centering the needs queer & disabled needs. he is devoted to the Land and to achieving reproductive justice for all in his lifetime. @earthybutchqueen