Monique Meloche’s exhibition Royal Specter, featuring work by the artist Kajahl, is in every aspect a museum-quality exhibition. I am not merely referencing the historically traditional and representational style of Kajahl’s paintings (that is to say, portraying a ‘likeness’ of the subject—and whose likeness is it? More on that later). I am also not just referencing the artist’s unbelievably skilled use of oil paint on canvas—materials that are, again, traditional. As Kajahl’s paint renders abundant silk folds, fine furs, and ornate gold, both the medium and style which together demonstrate a high level of skill, are historically deemed as having high value. However, when I say “museum quality,” it is not because of the undeniable attention to detail and quality of the work itself. Instead, it is because, upon gazing on the works, my mind ultimately and immediately places them within an art historical context. With each piece referencing so many elements of historical portraiture, Kajahl’s works are itching to disrupt the canon, demanding to reimagine the (absent) place of the Black figure in the history of European portraiture.

Kajahl’s paintings in Royal Specter are specifically looking back to the history of Blackamoor: decorative objects that were created by artists in the 17th-19thcenturies. Due to European colonial expansion in North Africa, these objects were commissioned and created for an audience who had never before seen people from this area (i.e. Black people). Most of the time, even the artists themselves had never been to these areas. So, they made things up—they made up details and created a fantasy of the “other.” In Kajahl’s paintings, these figures of fantasy come to life—but as he himself sees them. Through this, he is “creating a fantasy painting about a fantasy.”

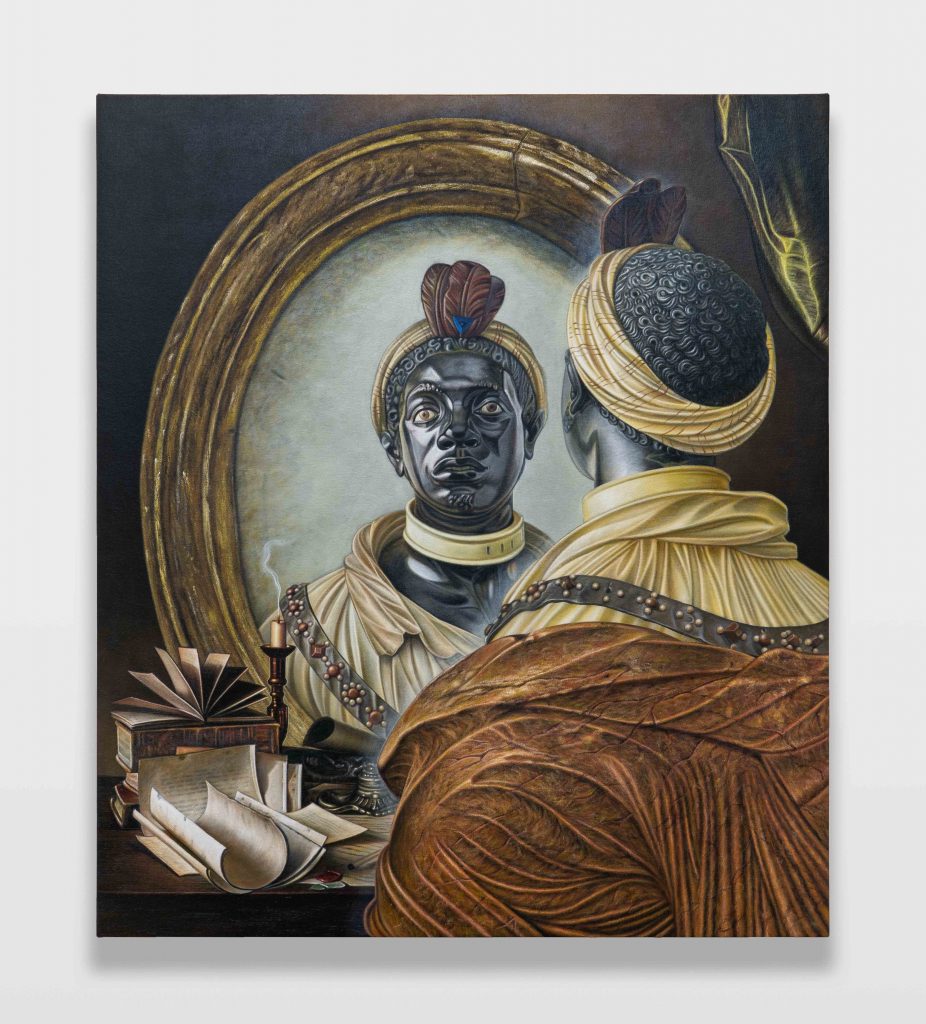

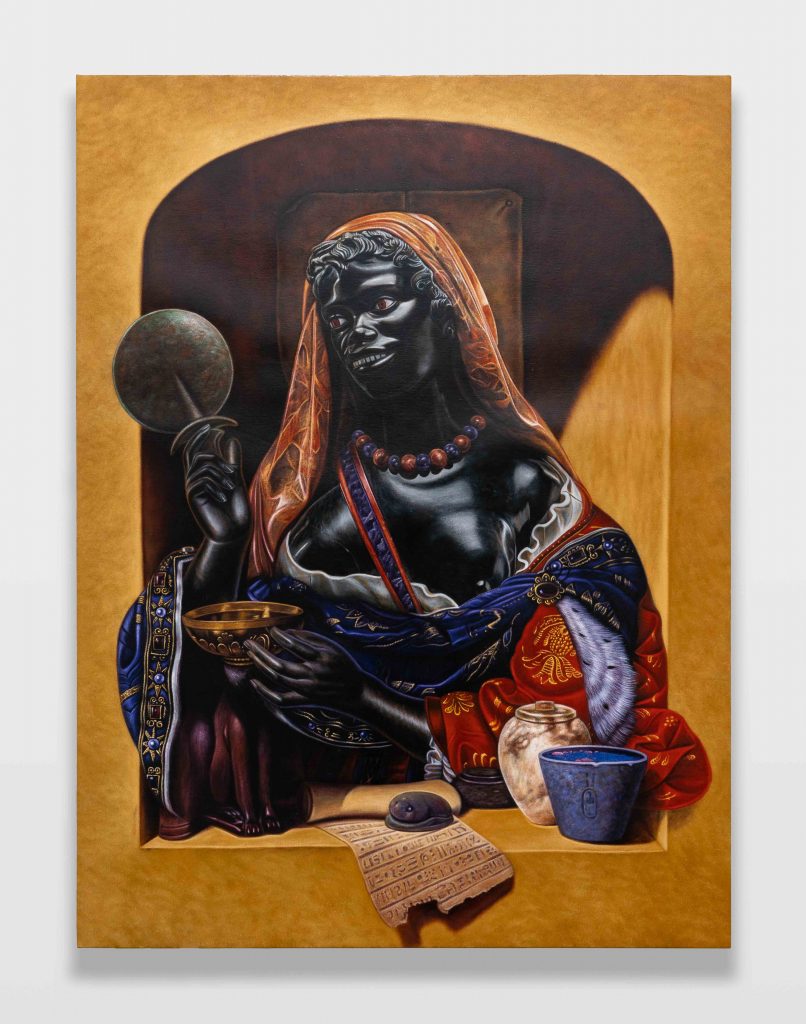

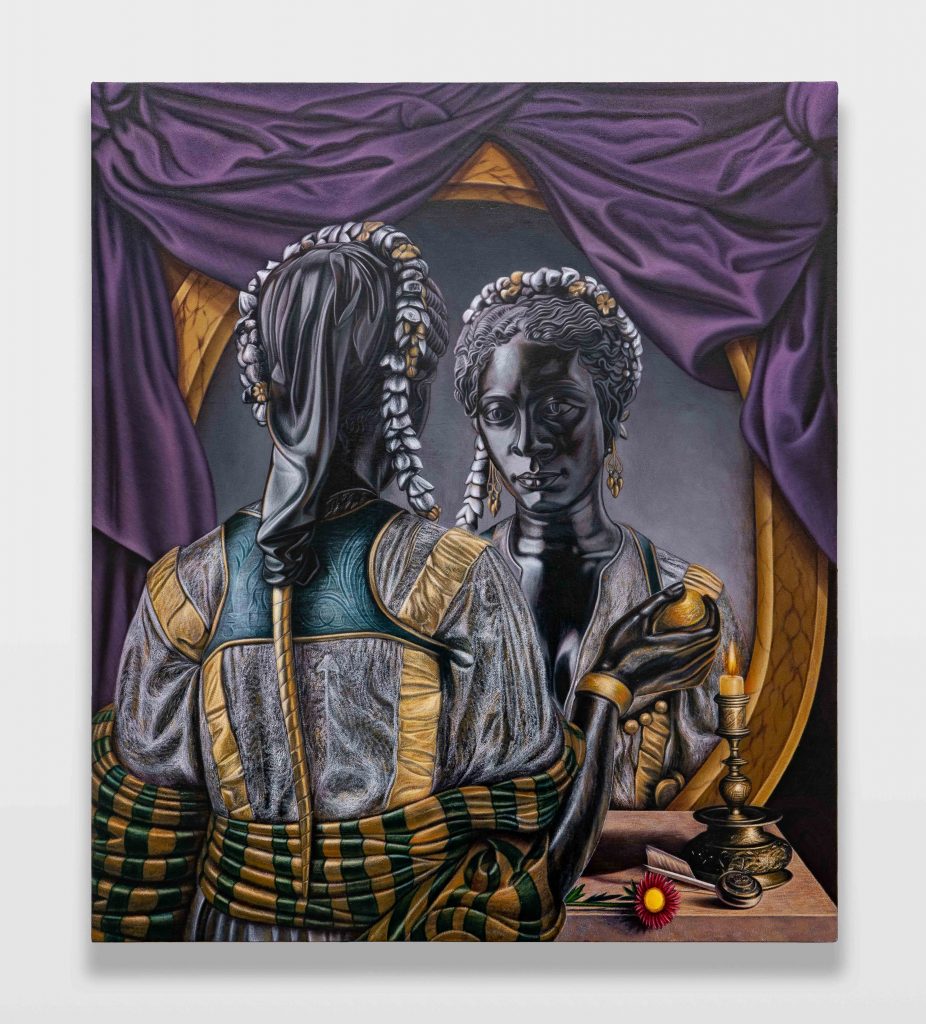

As many of these Blackamoor objects were sculptures, Kajahl renders the skin of many of his figures shiny and stone-like, much like that of a sculpture. In the exhibition, four paintings hang together; three of which have subjects that adorn this slick, statue-esque skin: Silent Incantation I & II, and Oracle (Holding Mirror). Each figure looks deeply into a mirror, examining their chrome surface, flesh that appears as if it, too, has the capability to reflect an image back to us. In contrast, the fourth piece, Oracle Snake In Globe, holds no mirror, no reflection, and whose subject notably has brown skin, a tone that does not convey artificiality, but one that is deep and rich in variations and detail. And unlike the oracle’s counterparts who surround her in the gallery space, this majestic and stoic, purple-haired woman looks not at a mirror, but directly at the viewer. She is not a reflection of a reflection. She is the subject in her own right.

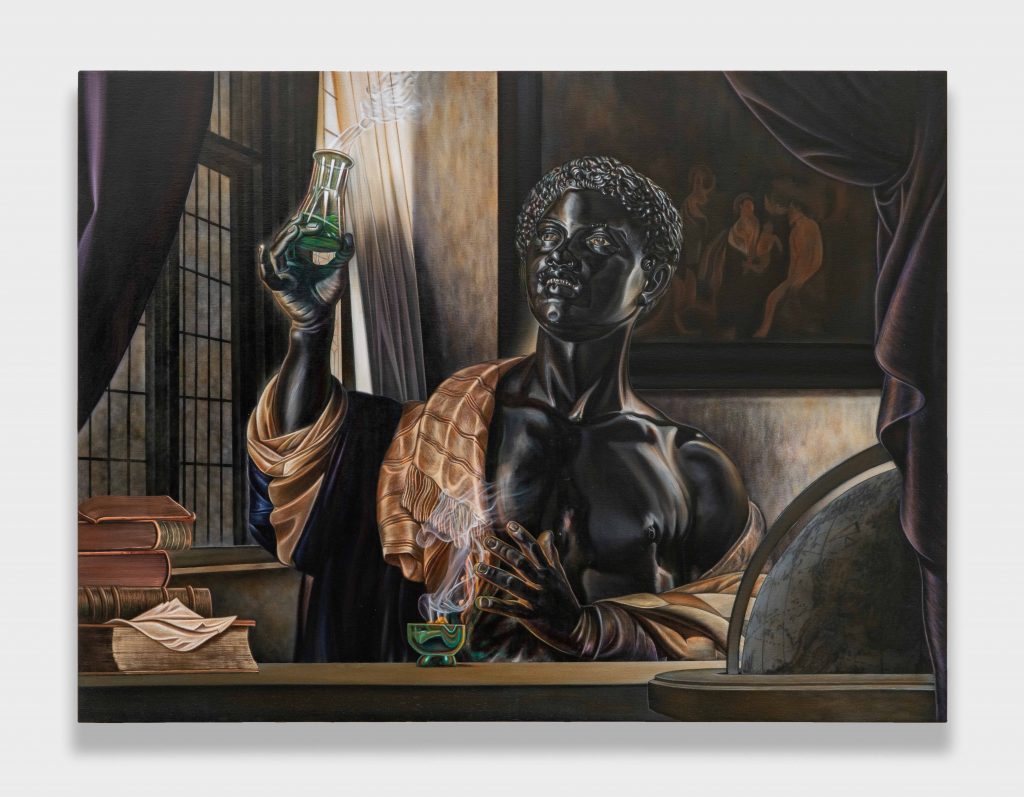

In the next room over, more stunning visions of an imaginary narrative: an epic fantasy of figures that are already fiction. In the larger than life piece In Huntress In Oasis (Astride A Crocodile), the scene is preposterous, portraying a jewelry-clad figure holding a spear and shield while riding an alligator, complete with a blue-smoking volcano in the distance. Here, Kajahl is forming a new fantasy, a narrative that he controls, as he says, “My fantasy is gazing back at their fantasy, I am their fantasy and they are mine…I am the Specter of their Imagination.” Through his paintings, Kajahl is both poking fun at the laughable inaccuracy of Blackamoor (as well as many other Black figures that show up in the Western art canon), while also plucking these figures right out of the colonial artistic hand and into his own. He is masterfully and cleverly inserting the Black figure into scenes that appear as if they are from the times of Rembrandt or perhaps the Industrial Revolution, which was, like Kajahl’s paintings, ripe with alchemists and philosophers (see An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump,1768 by Joseph Wright ‘of Derby.’)

Kajahl is, in essence, placing his subjects back in time within the canon, while at the same time recognizing the Black figure’s absence within it; and not only their absence but the utterly misrepresented Black body painted by white hands that often did appear during those times. His works bring to mind all of the times (and there are infinite) that a white, European artist has taken large artistic liberties (i.e. misrepresentation) when portraying Black and Brown populations (think Paul Gaugauin’s paintings of Tahitian women). Other times, figures with dark skin were later painted over to look white. Like art history (and, well, all of history) Black figures in European paintings and/or in Blackamoor were not the whole truth, but an imagined truth that fit neatly within European standards.

When gazing at yourself, like the woman in Silent Incantation II, one often thinks of the inner self. Who am I? Who is the subject, who were they created for, and who are they now? Kajahl has taken the sculptural objects of Blackamoor and breathed new life into them, a life in which they can lead their own fantastical, and often mythical lives, and examine themselves—away from violent, colonial-roots that led to their creation.

Kajahl’s solo exhibition Royal Specter is on view at Monique Meloche Gallery from November 7 – December 19, 2020. The gallery is currently open by appointment only.

Featured image: Kajahl Huntress In Oasis (Astride A Crocodile), 2020, oil on canvas, 66 x 84 in. The painting depicts a Black figure on top of an alligator. They are carrying a spear and a shield. In the background, there is a waterfall and a volcano with blue smoke rising above it. Courtesy of the artist and Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago.

Christina Nafziger is a writer, editor, and curator based in Chicago. Her research focused on performativity within the image and the effect archiving digital images has on memory and identity. Her recent writing investigates the work of artists with research-based practices as well as the role of the archive and its capacity to alter and edit future histories.