“Intimate Justice” looks at the intersection of art and sex and how these actions intertwine to serve as a form of resistance, activism, and dialogue in the Chicago community. For this installment, we talked to Manal Kara about living in the woods, the thousands of sexes in fungi, and BDSM subculture.

SNL: Where are you from originally? What brought you to Chicago?

MK: I was born in Pennsylvania but grew up in England and Kansas. My parents are from Morocco and the rest of my family all still live there and I have dual citizenship. I moved to Chicago on a whim 12 years ago.

SNL: Can you talk about living in Gary, Indiana? How has your art practice changed since moving there?

MK: I live in a big forest on the dunes. My relationship with non-human organisms has deepened considerably, which has had a huge influence on my artwork and my intellectual interests more generally.

SNL: You work in a variety of medium. Can you talk about your craft based work, like your ceramics?

MK: I have no formal art background or education. I’m self-taught. So for me craft was the accessible entry point into making things. With craft mediums you can watch videos on Youtube on how to make anything. Art has this kind of barrier to entry, like all these esoteric words and concepts that, as an outsider, you don’t really feel empowered to engage with. It’s really annoying because even artists who talk a big game about being anarchists or marxists will still use this willfully obtuse language that they learned in art school, even though in theory they believe in making shit accessible to everyone. I think it’s incumbent on anyone with a certain privilege to make sure their work is accessible to people without that privilege. So yeah, my use of craft mediums has largely had to do with thinking that that’s what I could do, or was allowed to do. Also, I think that I was drawn to ceramics and leather because they lend themselves well to expressing feelings of body horror, violence, and brutality.

SNL: Can you discuss how your work takes aspects of sexuality and includes it in your work, whether that’s explicitly or not?

MK: I’m fascinated and confounded by what is and isn’t considered sexual in our culture. Especially since the world has reached “peak humanity,” so to speak. Sex, traditionally, is bound up with notions of reproduction, of self-preservation, of replication and proliferation. Slowly, through human history, owing to the increasing complexity of consciousness and who knows what else, humans have been able to project the impulse toward self-replication onto the arts, written history, the concept that their intellectual output might refer back to themselves in the same way that one’s offspring refer to them, point back to them. So I feel like at some point there was a splintering, because sex still means self-replication activities, but it also means these activities of exchange, of information and sensation exchange with other entities, and like, it got to the point where sexuality is this cluster of concepts that admits vagueness and internal inconsistencies. I’ve always found it fascinating, especially since my worldview has become increasingly de-anthropocentrized as a result of living in the woods.

As a queer person, and a person who has always felt extremely alienated by binary gender, it feels really validating to learn about and live among fungi who have thousands of sexes. Even plants have tons of sexual modalities compared to what is accepted in human dominant cultures. Sexuality is so all-pervasive, I feel that it’s always been a subject matter for me not necessarily because I choose it, but because I choose not to willfully exclude it.

SNL: Can you discuss your inclusion of BDSM subcultures in your work?

MK: Sure, I think it’s a matter of working with what I know, I’ve been involved in various kink scenes for years, helped run a couple spaces, and had my own leather gear label for a while. But besides the consensual play aspect of it, I’m also interested in the real, sometimes brutal, human tendencies that BDSM uses as a fantasy conceptual framework: hegemonic power, retribution, incarceration, cruelty, submission, erasure of the self, etc.

SNL: I’ve seen some of your work including text, or words. Can you expand on those?

MK: Yes, they’re basically little poems that I come up with, thoughts I have and write down. Sometimes they might be aleatoric poems composed from names of plants or other organisms in the order in which I encountered them. Then I situate them in physical objects with visual references that I’m feeling at the time. I always used to think text-based art was cheesy, but I’m changing my opinion now. Words are really my wheelhouse, probably as a result of being an ESL third culture kid and a gemini.

SNL: And what are you working on lately? Any news or upcoming shows?

MK: I’m working on a series of sculptures for my upcoming solo show at Hume, tentatively titled “Panty Hoes at the Dawn of the Chthulucene.” I’m also developing a series of videos entitled “Ode to Slug Body.” It takes its name from Slug Body, a conceptual benevolent inhabiting spirit that I adopted to guard against dry heat, windiness, and anxiety. It’s going to be a series of short erotic films exploring earth-based BDSM, earthbound sensuality, interspecies encounters, and deanthropocentrizing eros, among other topics. I also have a show at Fernwey coming up later this year.

Immanentizing the Eschaton, is on view through April 15 at the Shoebox at Sector 2337

Immanentizing the Eschaton Exhibition Review By Willy Smart

Common names of plants are notoriously slippery. A given name often refers to separate species in different locales, or multiple names to a single species. Skunk cabbage here is not the same as skunk cabbage there. Latin taxonomies attempt to sidestep this indeterminacy, privileging reproducibility as the basic criterion for group identity. Though its neatness breaks down when examined, the grade-school definition of species largely holds: a group of organisms that can produce fertile offspring. However, common names of species are structured by a different logic—one that speaks less to a species’ self-perpetuation than its relational effects on its environment (which, of course, includes humans as well).

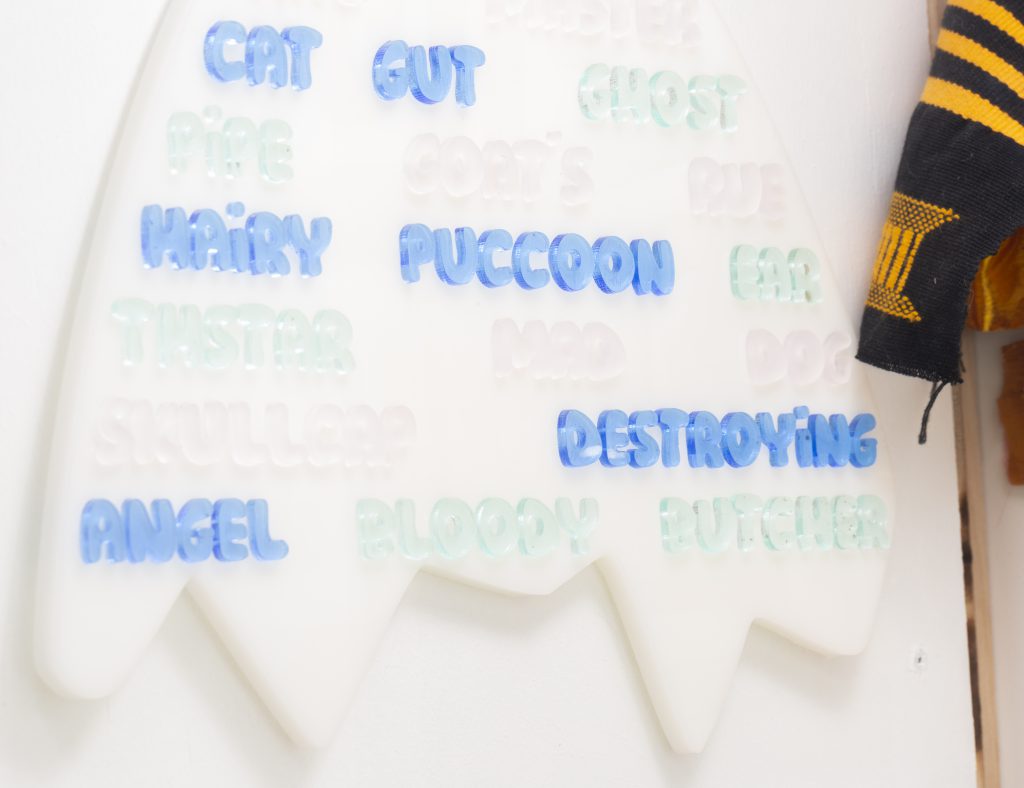

Artist Manal Kara’s small-scale installation Immanentizing the Eschaton is the first to be hosted in Sector 2337’s Shoebox Gallery, “an experimental micro gallery” situated in a street-facing, glass-faced box originally built to house a restaurant’s menu. The installation presents itself as a model—the wooden floor and white walls of the box’s small confines suggest an architectural mockup, not to mention the teleological initiative evident in the project’s title. “Model” though hangs as too technical a term for the installation’s ambitions: “spell” sits closer.

Spelling indeed is a primary element in the installation. On one wall, laser-cut acrylic letters spell out common names of plants mostly endemic to Kara’s home near the Indiana Dunes, reading: “Rattlesnake master: so called for the plant’s purported antidotal properties, or else so called for the rattling sound of its dried seedpod. Goat’s rue: so called for its poisonous effects on goats fed its root in hopes of boosting milk production. Mad dog skullcap: so called for the faith the plant might cure rabies. Destroying angel: so called for its pure whiteness, its haloed veil that encloses its stem, and the consequential effects of its ingestion.” On the other two walls, two different spells: opposite the litany of common names, “baba yaga laid an egg;” and opposite the glass window, “jupiter’s bib and other pleasures / jupiter’s bib is infinitely accessible.”

Baba Yaga, the forest-dwelling being of Slavic folklore, is an ambiguous figure, serving alternatively to lend heroes magical assistance and to attempt to consume them. Ambiguous, too, at a semantic level: in Old Russian, baba means “sorceress,” “midwife,” “fortune teller” but can also serve as an appellation for nonhuman beings: mushrooms, cakes, pears. The destroying angel mushroom Kara refers to is most easily identifiable by its volva, a white, egg-like sac that encloses the stem from its base. In older specimens, the volva retreats underground and must be carefully uncovered. The house of Baba Yaga, deep within the forest, sits on chicken leg stilts. The comparative mythological studies common to the 19th and early 20th century frequently chart equivalences of mythological figures from different cultural traditions. (For instance, the Slavic god Perun equals the Roman god Jupiter; the Vedic deity Pushan a cognate of the Greek god Pan.) Baba Yaga, however, is singular: a species without a Latin name; a common name without a reproductive taxonomy.

Baba Yaga’s egg then isn’t going to be fertile, at least not in a straight sense. In Kara’s installation, the list of common plant names rendered in pastel plastics is inlaid over an egg shape that has been broken in half. The open egg says, “there’s nothing in here.” Or, “what’s in here isn’t for you.” Or, “the shape of the universe isn’t an egg.” The common names of plants read as a recipe or a roster. Like the infertile egg, they point to forms of reproduction separate from the biological forms governed by Latin names: the reproduction of fantasies. A common name speaks not to a species’ past (its genealogy) but its swerve: the relational effects of the plant on its cohabitants. Plants don’t hold the only—or even the most present—poisons in our ecosystems, but the common names of plants crystallize the more phantasmic aspects of these poisons and our imagination of our intoxications under them.

Despite this evocation of ecology, it’s clear these effects summoned are not all life-giving, creative, maternal effects—after all, this is “immanentizing the eschaton.” Hence the “devil’s shoestring,” the “queen of poisons”, the “destroying angel,”: all poisons, along with many of the other plants in the roster. Not to say though that Kara’s work is all gloom—doom, yes; gloom, no. The most prominent text in the installation says otherwise, hanging syntactically as an alternate title, a suggestion rather than a statement: “jupiter’s bib and other pleasures.” Below the line “jupiter’s bib and other pleasures” hangs a halved scallop shell. Adults don bibs when eating shellfish and cephalopods. Unlike the bib that is worn by adults when eating shellfish or cephalopods, this bib isn’t there to contain dribbles. It is there to facilitate them. These are the other pleasures. And below the scallop shell, the line, “jupiter’s bib is infinitely accessible.” The shape of the universe isn’t an egg. It’s a bib.

Kara’s installation is about time. That’s to state the obvious. The poisonous plants, the eggs, the bib open onto fantasies of coming, endings, and endtimes. The work’s materials mark this opening as well. Plastics, as we know—like the acrylic of which this installation is largely composed—entail a duration of decay beyond anything we can really reasonably comprehend. However, the installation doesn’t call on its viewers to alter their behaviors lest they hasten an anthropogenic apocalypse. No implicit imperative to recycle more, to consume less, to become more eco-friendly. The plastic of these spells ensures their persistence. That future—the slow decay of plastic and the plants that will outlive our names for them—is one of the timelines Kara wrangles here. But interwoven with this far future is another timeline: the one that is already here, in which we can’t imagine an endtime because we’re already in it; in which the name Jupiter summons not the planet nor the Roman deity, but Sailor Jupiter of Sailor Moon with her rose earrings and flower hurricane attack; in which we’ve all got tattoos of barbed wire and stylized tribal flames like those cut out of acrylic that litter the floor of the installation. A future so far off one’s relation to it can only be phantasmatic, and yet a present so close one’s relation to it can only be phantasmatic: this incongruence and overlap is what we’re living, baby, baba, yaga.

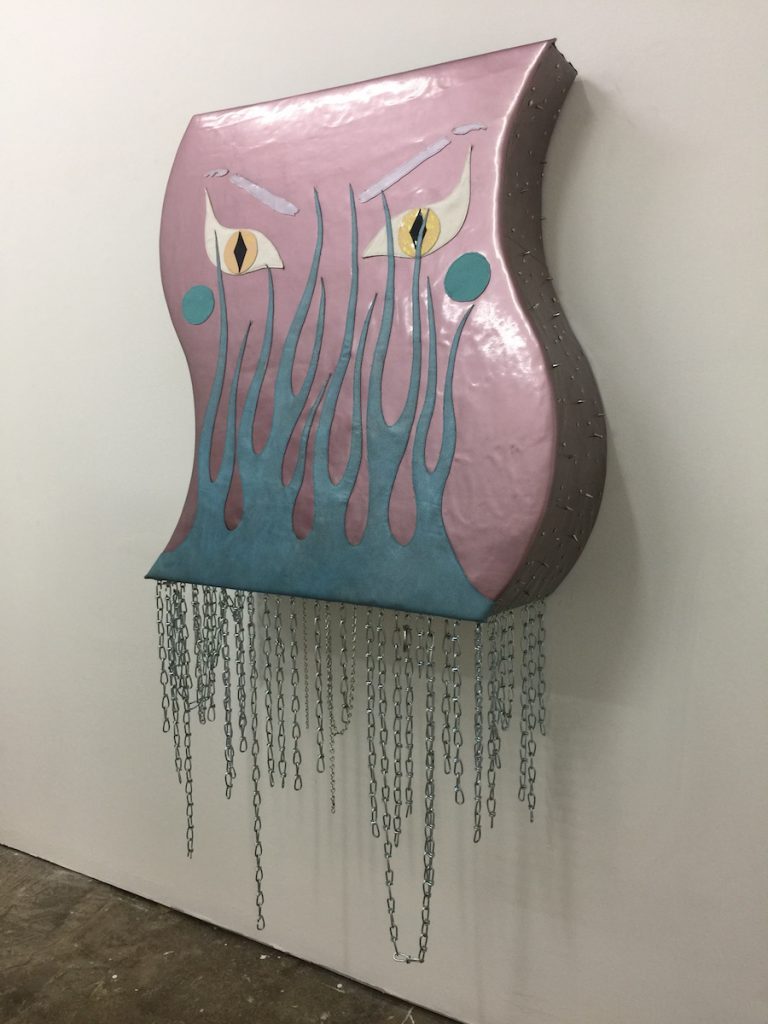

Featured Image: Photo by Boyfriends Gallery, exhibition: 100% Raw Acid House Hoes Against Empire & Capital

S. Nicole Lane is a visual artist and writer based in the South Side. Her work can be found on Playboy, HelloFlo, Rewire, SELF, Broadly and other corners of the internet, where she discusses sexual health, wellness, and the arts. Follow her on Twitter.

S. Nicole Lane is a visual artist and writer based in the South Side. Her work can be found on Playboy, HelloFlo, Rewire, SELF, Broadly and other corners of the internet, where she discusses sexual health, wellness, and the arts. Follow her on Twitter.

Willy Smart is an artist and writer who works in presentational and propositional forms. Willy makes lectures, sculpture, and publications that propose extended modes and objects of reading and recording. Willy directs the conceptual record label Fake Music (fakemusic.org)

Willy Smart is an artist and writer who works in presentational and propositional forms. Willy makes lectures, sculpture, and publications that propose extended modes and objects of reading and recording. Willy directs the conceptual record label Fake Music (fakemusic.org)