In March of 2020, as lockdown orders went into place, there was much collective confusion, complaining, and panic. Folks were upset about not being able to be in spaces centered around socializing, entertainment, or arts/culture/leisure. For many disabled folks, there was less panic around needing to stay home—we are used to this in fact. There was, however, much disabled frustration stemming from the fact that non-disabled folks refused to stay home, refused to think about collective wellness, and refused to unpack their ableist expectations of living in this world. For those of us with disabilities who are fortunate enough to have a place to call home, home is often our sanctuary, if not the only place that feels safe and accessible to us. I often talk to my disabled friends about what our disabled sanctuaries look like, both in reality and in our wildest fantasies. In this interview, I spoke to interdisciplinary artist, writer, and spiritualist, Jade T. Perry.

You can read previous iterations of Disabled Sanctuary here.

This essay was conducted via email and has been edited for clarity and length.

carrie sarah kaufman: How do you like to introduce yourself and your work?

Jade T. Perry: “Jade (she / they) is a BlackQueerDisabledFemme on a mission. Jade T. Perry (M. Ed) is an interdisciplinary artist, writer, speaker, educator, coach, and spiritualist. The mission of her work, as a whole, is to contribute resources, art, narratives, and experiential learning opportunities that aid in the holistic healing processes of Blackfolk, Queer and Trans Black and Indigenous People of Color (QTBIPOC), and disabled and / or chronically ill folks within these communities. The other part of that mission is to engage non-Black people and people who can meet their primary needs with plenty of ‘disposable’ income to fund initiatives that directly impact the creative and spiritual development of Black folks.”

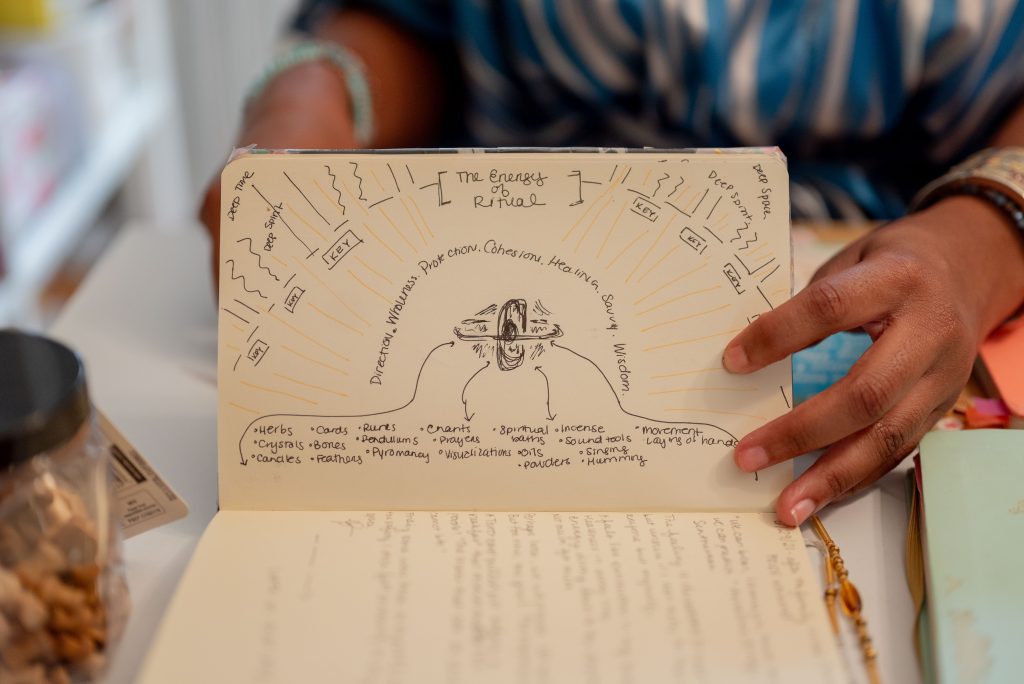

That’s the formal introduction. At base, I think it’s important that folks know that I’m trained in both Integrative Arts with a focus on Performance Art and Creative Writing. I’ve also studied Higher Education and spent focused time in that industry, honing my thoughts on liberatory education. There’s a spiritual, social, and educational justice undercurrent to the work. One thing that I know, in my bones, in my lineage, is that there is never a colonization or oppression of the body without the oppression of the Spirit. So, themes in my work include Black Feminist Healing Praxis, Afrodiasporic Spirituality, Creative Healing and Divination as an art form. I also know how life-changing it is to have opportunities for deep study. That’s what I’ve loved most as an educator, independent scholar, and writer. At the root, I’m an alchemist. I’m blending disciplines to provide written work, experiential learning opportunities, coaching, courses, healing circles, consultation, one-on-one spiritual care, and workshop/keynote facilitation.

But I don’t want to talk about all of that without contextualizing it. One of the realities of my work is that I have to navigate a digital landscape. Sometimes, that landscape decontextualizes an artist and limits the understanding of an artist’s work. So here’s what’s also true…

I’m also a lapsed nonprofit worker and Executive Director. I’ve survived capitalism in West and Southwest Philly, and I’m surviving capitalism in Chicago. I’ve worked full-time to fund the art. I’ve had a stint in a spiritual supply shop. I’m a former background singer. And I’ve experienced chronic pain and illness for the majority of my life. In a 3D context, all of this impacts the ethos and the rhythm of the projects that I do. It also informs my idea of sanctuary. I think about that concept quite a bit.

csk: Thank you for this multi-dimensional picture of you. What are a few words that describe that rhythm that works for you?

JTP: During my time at The Mystic Soul Project we had a saying: Rhythm over time. So, I appreciate you asking about idiorythmy (individual rhythm). I’m most centered when I’m able to move slowly. My rhythm is nocturnal a lot of times because the feverish pace of the 9-5 has passed, along with its endless demands of urgency.

For the most part, I see myself as a time fugitive. I live in a BlackDisabled body. My ancestors had to navigate toward freedom under the cover of night. Claiming their freedom also meant periods of nocturnality. There’s something about the “get up early, work all day, crash at night, do it all again” rhythm that feels wrong to me on a spiritual & ancestral level.

Finally, nature gives me a lot of models for alternative rhythms and I’m grateful for that. I’m obsessed with slow-moving animals like sloths, turtles, and koalas. They’re really a model for time anarchy!

csk: Do you have a place that you would call your disabled sanctuary? What does it look and feel like? What do you love to do in this space?

JTP: My bedroom is my disabled sanctuary. There aren’t many pictures of me in that space. I don’t want to share too much about it. It’s that holy to me. What I will say is that it’s a place where I’ve tried to channel softness. It’s a place where I meditate and rest. There are so many sensory delights in that space—things to hold, to smell, to play with, to stim with, and to experience. I have books all over my space, but the most intimate reads are in my bedroom.

It’s not the fanciest place, but I’ve made it mine. It holds my most secret desires and needs with tenderness. I think that’s one definition of a sanctuary.

csk: Keeping the bedroom sanctuary sacred and secret makes so much sense to me. As disabled people I feel like we are forced to reveal everything all the time in order to get our needs met. I’m glad you have cultivated a space that meets your needs for comfort and softness.

JTP: Yes! Some things aren’t for public consumption and there’s a lot of power in reclaiming a right to privacy as a disabled person.

csk: You talk a lot about delighting our senses, and also about making things as easeful as possible all the time. Given that we’ve talked about and exchanged snacks quite a bit, I wanted to ask—what are some of your favorite easy and delicious things to make for yourself? And what are your favorite things to receive that others make for you, in the kitchen?

JTP: My friends and family are spread far and wide. So it’s really special when others make delicious things for me. It really communicates so much love. I took a trip to Portland to see two dear friends, and we stayed together for four days. There were salmon croquettes. There was bread pudding. There was bone broth made from scratch. There was a cabinet full of snacks: popcorn, chips, crackers, peanut butter, pita chips. There was hummus in the fridge, apples, blueberries, bananas… just an abundance. And coming into that literally made my nervous system slow down. It was so relieving and delightful. Because we talked about what we could give and do. I’m not the femme who cooks, but when it comes to working herbals and roots, I know that. I’m a snacking Taurus, so I always have the grocery list sorted. There are other ways to give. To me, it was just about the collective care.

csk: What’s one of your favorite ways to use herbals or roots?

JTP: “Working” roots is a staple of many Black and Afro-diasporic ways of living. Sometimes working those roots means making a tea or tincture. Other times, working roots means utilizing nature’s gifts plus your own magick, specific oils, incantations, and/or petitions in order to create favorable circumstances. I have a deep appreciation for all of it.

In my own life, I do a lot of teas and decoctions. Growing up, there was always some kind of tea that my Grandma or Mom would offer in addition to any other medicines I was taking. They were taking a holistic approach even before folks were using that language. So, I like to keep that tradition going.

csk: I love the way you cultivate online community, it almost seems like you are creating a bit of a disabled sanctuary, virtually. How do you feel about your “e-cousins” as you call them?

JTP: I love the e-cousins! I really have a lot of gratitude for the folks who resonate with the work and travel across time (zones) and space to experience it. Initially, I started talking about “e-cousins” because I hated the word “followers.” I was looking for a word that indicated a different kind of orientation. The concept of Ubuntu is important to me and I’m thinking about this again now because of my e-cousin Jasolyn Harris, LCSW, M Div. This is a concept that has many different words in the Afrodiaspora but it essentially places the importance of existence on interdependence and inter-Being with others. It’s a reminder that we have communal matters to tend to. It’s about the invitation to share gifts and thoughts and perspectives without being so focused on one individual to “follow”.

I have a large family and some of that is biology. But a lot of it is because Black folks have this artistic way of family-making and grafting “cousins” in. Your cousin or your aunt doesn’t have to be related to you by blood because they’re related to you by communal orientation, or by spirit, or by circumstance. So, having lots of cousins with varying relationships is something that I was used to.

With the e-cousins, it’s a term of endearment. “Followers” and “e-cousins” have a different energy. Followers can easily become voyeurs. E-cousins are folks who have some sort of practice of reciprocity. Many are patrons of the work and we get to see each other, chat both live and asynchronously at least once a month. There are community agreements and we try to honor those. There are some who are really involved and others who support from afar. I appreciate it all. I really appreciate it when folks move past it as a social media concept and embrace where the work is more contextualized and where there is dialogue process happening.

csk: How has your creative process changed over the course of this past three and a half years of navigating Covid and all of the ableism that we have seen and experienced throughout it?

JTP: I think it’s forced me to remind folks that disabled creatives were navigating ableism before this. We were making spaces before COVID-19. We’ll create sanctuaries after this, too. Some will exist for a long while and others won’t. That’s okay; that’s life as an organic process. What matters is that we’ve created spaces of respite in a world that doesn’t readily offer that up to multiply marginalized folks.

I have to remind myself of that. The depression is crushing when I don’t. It’s been a heartbreaking three and a half years, in so many ways. It’s had me thinking deeply about isolation. This is a theme that is coming up now a lot more in the dialogues I get to have.

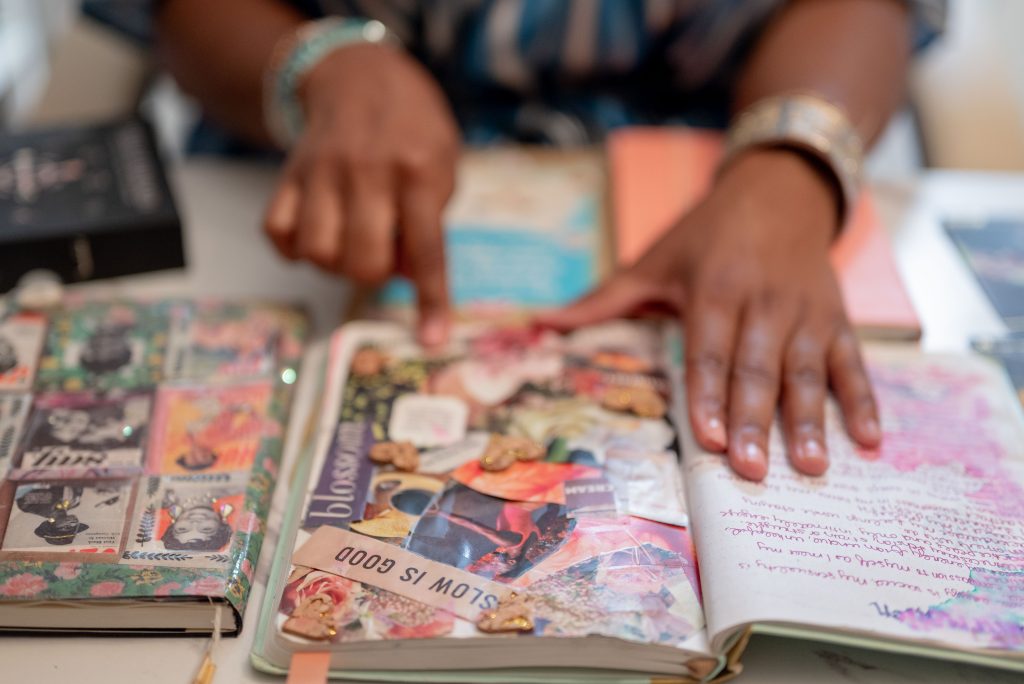

It’s rekindled my journaling practice. Keeping a journal has been important to my creative process from a very young age. As I got older, I’d let other things take the place of that time I’d spend with myself. Once the pandemic started, I was having these disabled visions of where we were, the limitations of our medical system, and the type of communal care that was needed. Deep down, I knew I needed to have a record—even if an informal one. Something to name the experience for myself. Zora Neale Hurston said, “If you are silent about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it.” It’s been so painful to watch these creative, artistic, and “liberatory” spaces gathering without COVID protocols… after a three and a half year opportunity to develop them. I’ve wished for that creativity to extend toward how we care for one another in a real, embodied way. So, I try to focus on what I can control. I can make sure that there is a creative record. I’m not promising external writing on this, but I will say, that many things in my journal become useful compost for other forms of art.

csk: Your teachings and everything that you share in readings and online are so generous and important. I’m so grateful to be able to learn from you and witness you. What disabled femme wisdom can you offer us in this moment? I am wondering what your new normal looks like, and about all the things that feel exciting to you about not returning to the old normal.

JTP: Thank you! It really is an honor to know that you enjoy bearing witness to the work! My new normal is trying to embrace Change. And trying to get this book written. I’m excited about those things… 80% of the time. Haha!

A piece of disabled femme wisdom that I like to share is “Make the Magick Easeful.” I’ve built that phrase out so much so that there’s a course on it now! But at its heart, that saying is about co-creation. It’s an invitation to make (shape, form, and co-create) the magick (of our art, our work, our “aesthetics of living;” bell hooks) full of ease. Wherever we can. Sometimes, we can do that in big ways. Sometimes, the ease is in the way we invite ourselves to breathe. It doesn’t mean things are easy. Making the magick easeful is about life as craft work and knowing that we have a right to experience support and care from ourselves and others.

To find out more about Jade’s work, you can find her website here and connect with her on Instagram here.

About the author: Carrie/cherry sarah Kaufman is a queer, multiply disabled, white, jewish artist, community organizer and kitchen witch. She is in love with supporting other disabled survivors and is currently studying to become AASECT and ANTE-UP certified to continue offering sexuality education grounded in the principles of Disability Justice. Cooking, ritual and poetry are her current tools for connection and healing. Her work explores disabled embodiment, erotics, survivorship, care and intimacy as well as Jewish magic and spirituality. She is the creator of DisabledParts.com, a website featuring stories about disabled sexuality. She is full of fire, water, and honey.

About the photographer: Tonal Simmons (they/them) is a Black queer non-binary artist who is a writer, photographer and painter. Their photography and painting seeks to examine the similarities between flowers, growth, and Black queerness. While their writing explores the idea of DEI within art, creating w/chronic conditions, & lack of access to art for Black and brown creatives. You can check out their personal work at www.tonalscorner.com