Edra Soto has transformed the Commons at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) with her work Open 24 Hours into a beautiful place filled with remnants of histories that gives birth to transcultural discourse and new meaning. Fittingly, Soto’s culturally charged work is the inaugural project for this new “civically engaged space” at the MCA. As I walk in to the Commons to attend Edra Soto’s artist talk, there are installations of intricately designed, custom-made display structures that stand like pillars, shelf after shelf holding up empty bottles of all different shapes and sizes; the translucence of the greens and browns of the bottles providing a striking contrast to the opaque white of the shells that adorn their surfaces. Edra Soto informs the audience that she collected these bottles, and continues to do so, in her neighborhood of East Garfield Park. She picks them up, washes them, removes their labels—she cares about these bottles as objects. She sees something in them. They are not pieces of trash to be discarded and forgotten, they are pieces of history: her neighborhood’s history, her history, our history. Through her journey collecting these relics of the present, Edra Soto becomes an archaeologist; a historian discovering new connections across different histories. She integrates these relics, these empty liquor bottles, into the larger narrative that her installation Open 24 Hours encompasses; offering a pathway between her present life as an artist in Chicago to her past growing up in Puerto Rico.

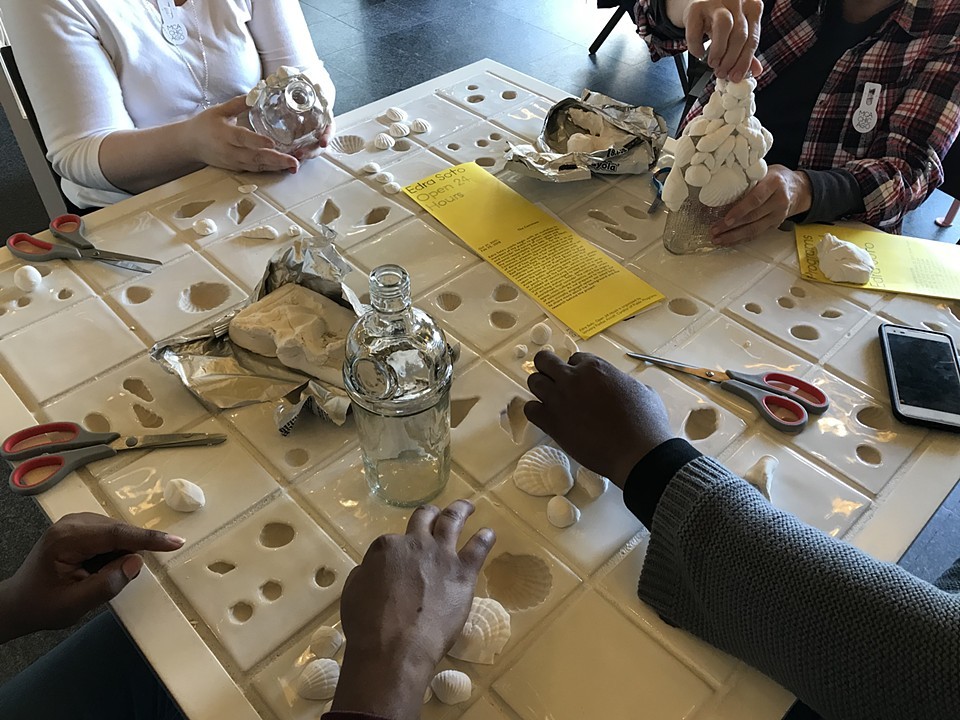

Soto has created a space with this project where she not only presented her talk but also spawned community workshops and a number of performances and DJ sets. With Open 24 Hours, Soto invites you to join her, to collaborate in her art, to be a part of a community—a history. During her artist talk, Soto asked, “How can we celebrate our existence?” And that is exactly what this project does. It pulls at the seams of the hierarchy of cultural and historical significance and invites you to draw from personal experience and local community to celebrate who we are. This is where Edra Soto and I begin our discussion, with her own unique cultural experience calling two places home, and her relationship with both communities and histories.

Christina Nafziger: There are so many events and workshops that are happening in conjunction with Open 24 Hours. Can you tell me a bit about the related performances and their connections to your work?

Edra Soto: Yes, there was a performance that happened December 15th and it was about the clashing of two cultures. It [was] a way for me to have a conversation about my relationship with American culture and where I grew up, which is Puerto Rico. I lived there for 25 years and I’ve been in the U.S. for over 20 years. I always need to address this in my work. I find this relevant for how my work becomes connected with different kinds of communities as well as the complexity of being Puerto Rican. My work is a way for me to talk about how complex these relationships can be.

CN: Yeah, I love that. You put it so well. When you were discussing Open 24 Hours at your artist talk, you spoke about learning through movement and gesture, and about your experience physically picking up and collecting the bottles for the work and learning through that. That really resonated with me because I’m a big believer in muscle memory and people collectively doing actions together to create new memories and histories. I wondered if you had anything to share about what you personally learned, especially about your neighborhood, through this act.

EN: Yeah, I described it like that. I feel like I’m lifting up a history. To me, those bottles are really important. I do care about my neighborhood and I keep picking them up, truly, everyday. I am fascinated by it—I’ve been fascinated by it since I started the project. That is how I know that it means something to me—through my fascination with how it behaves, how it speaks to me, and how I feel like I am understanding through all of this. I feel like I’m understanding what is happening.

CN: It reminds me of an archaeologist’s work, like you’re digging for bones.

ES: I definitely feel like there is a parallel there. It is a way of understanding a community. I think through garbage you can understand. You can see what people are consuming, right? But this became a particular thing because of the sector of the city, because of it being a historically African-American neighborhood. It’s very specific–and there’s no supermarket there. It’s a food desert, but there are liquor stores. There’s not only the consumption of the liquor from the area, but also the consumption of the music from the radio. I hear it all the time. Perhaps there are a lot of cars that have their stereo as their personal music but that music becomes part of the environment because it’s loud—you can hear it. And I think, I am listening to the same thing that everyone else is listening to right now because I listen to it through the radio since I don’t have an iPod. I feel like I have been consuming music from the radio for a long time. I love listening to it from the car. I love pop music because growing up in Puerto Rico mainstream culture was very much a part of my life, so there’s nostalgia to that. I’m also interested in what everybody else that is not part of the mainstream culture is listening to.

CN: I love listening to the radio, too. It’s so interesting and also strange to me that I could be driving in a car, and all the people in the cars around me could be listening to the same exact thing—we are all listening together, but separate.

ES: Yeah!

CN: There’s something really great about that, like you are connecting to the machine of the city through the radio.

ES: Yeah, yeah—it’s true! It’s so accessible—it’s right there.

CN: You work a lot in installation, and it really transforms the environment it’s in. After going to Open 24 Hours, I thought it was so interesting that you had the music playing in the background because I thought maybe that it was accidentally left on, but it was such a specific genre.

ES: So that music was happening because I invited the artist and DJ Sadie Woods–and you can find her on the MCA blog, there is an entry there that she wrote about her project. I organized 14 different performances and Sadie was one of them. All of the performances that are happening in that space under my name are organized by me. I curated those programs. I focus mostly on music because of the relationship of Cognac and music, especially now with contemporary hip hop and rap, and how I think of hip hop and rap as somewhat instigators of the consumption of Cognac. So many of the bottles I find and collect from my neighborhood, which are then included in my work at Open 24 Hours, are Cognac bottles. So it’s a complicated relationship. Sadie started a project of her own practice that is called social music so including her in this was a definite for me.

CN: Another thing that I love about the concept in Open 24 Hours is this idea of a vessel—the idea of a bottle as a vessel. They once carried something and now they are all empty vessels. And I was thinking, what does it hold now, what can it hold? You mentioned how people have these memories of celebration with certain liquors. So the first thing that came to mind was that these bottles now hold a new meaning, they hold a connection, a memory.

ES: Yes, they now hold a different substance. The stories of the different liquors are something that I can enjoy because I pick up the bottles and I’m seeing the groupings of the bottles, where they were. There will be a group of bottles, a particular brand, and the way I find them can say something about what happened. It is like, oh, that was an amazing night—somebody was sitting on the steps drinking, somebody was having a good that night. I find it the next day. Its weird, because they will be either laying on the ground or standing somewhere, on the sidewalk, by steps, on the grass—it could be anywhere, right?

CN: That’s interesting that you were talking about physical movement earlier, and now you are inviting all these people to do this physical creating with you at your workshops by decorating their own bottle.

ES: Yeah. Putting the bottles in other people’s hands is putting the responsibility of littering in their hands, which was my initial motivation for picking up the bottles, and a way of propagating the history of what those bottles are connecting, especially Cognac bottles and how they connect to African American history.

CN: I had no idea about this historical connection when you mentioned it that Friday at your artist talk.

ES: Yeah, there is a book that talks about the historic connection between Africa Americans and cognac called Bourbon Empire: The Past and Future of America’s Whiskey by Reid Mitenbuler. It speaks also about how through hip hop and rap the consumption of Cognac was kind of refurbished. It’s so fascinating to me. The history is all of ours because we all live here. When you’re an artist, to be able to see, to find a real life connection, finding meaning in something that is right there in front of you. I feel privileged.

CN: That’s a great way to put it. I think objects have this power, and so it’s really great to hear you talk this way about these objects that people would normally just pass by.

ES: Yeah, the bottles mean a lot to me. I clean them and I care for them. This to me is very special to me—having the bottles available to the audience. And they know they can come back and pick them up. That is the last part of the project. During the month of February everybody who has done the grafting project, who has participated in these workshops, can come back and pick them up.

CN: Oh, so they stay here after they are created initially in the workshops?

ES: Yeah, they stay here because we are showing them. We are kind of transforming them, transforming their appearance—

CN: So the collection keeps growing.

ES: Yeah! While they are here they are being transformed by the audience. They are going to have a new owner; they are going to have a new home. So hopefully people will come back to the museum in February and pick up their bottle that they made.

CN: You said you are going to continue the project. Do you have any vision of how you want it to grow in the future?

ES: I’ve been considering creating a new project with the bottles, with the same components, but inviting artist friends to decorate the bottles themselves, because they are my peers. That’s my community. It might not be anything too crazy in relationship to what I am doing now, but I think it’s a different type of meaningful. They are both meaningful experiences—having strangers decorate your work, and having it be there work as well. I was also thinking of different ways of displaying them. When they are displayed in a museum, it becomes one body of work. So I’m thinking of different ways of displaying the bottles and their craftsmanship, the decoration being featured. I’m part of a group show that is going to be happening in the summer of 2018 at the Smart Museum. It’s an exchange between Cuban and Latino artists. One really nice thing that I would love to do is have the Cuban artists, and all the artists, participate in this project.

CN: Yeah, it would be really interesting!

ES: Yeah, and I can also keep on with the concept of my project.

CN: Definitely! In your artist talk at the MCA, you spoke about the importance of bringing people together in the space in your piece Open 24 Hours. Is this a common theme in your work? You also mentioned The Franklin, which has a similar purpose.

ES: The Franklin is a project space that I decided to create along with my husband in the backyard of our house. It mainly came out of my relationship I have with the artist-run community, how through those communities I feel like I have found visibility as an artist. It gave me a career. My first exhibition here at the MCA was in 2009 when I had a solo show upstairs. Through exhibiting at spaces in Pilsen that were artist-run project spaces, curators would visit those spaces, and through that I eventually ended up here. It helped me understand the value of visibility, and that’s mainly why I ended up thinking that this is a way of living, this is a philosophy, and this is how we can have a way of maintaining and supporting a community.

So inside our house, my husband and I have a collection that we both have been bringing together either through me creating work with other artists or through artists giving us work when they show with us. They know I’m going to put it up on the wall and they want to be part of the collection. Our private collection ends up being public because when we open The Franklin during the opening hours, we have a lot of traffic coming in. We do this as a way of supporting the community.

CN: What an amazing project! That reminds me of a project you did earlier this year called Screenhouse that, taking the shape of a gazebo, also had this idea of creating a space.

ES: Yes, that was my first iteration of using graft within my way of using the vernacular language of architecture, in relation to the building that it is next to. It is right in front of the backyard of the Arts Club of Chicago. Usually the project is an architectural intervention, but instead of making a functional gazebo Screenhouse is almost like a net, like a pattern that is wrapped around the shape of a gazebo. It tends to bring people in and immerse them in its path—that was the concept. I would not recreate a pattern and make it an object for sale. It has to be either integrated as part of the architectural components or directly into the architecture. This project gave a little more independence to go outside of the form of a building but still give integrity to where the patterns are coming from. The pattern, the graft, is a symbolic transplant from Puerto Rico to the U.S. It is like if I was bringing a piece of screen or fence from Puerto Rico into the U.S. I want the patterns to always be exhibited outside of Puerto Rico.

CN: Can you define ‘graft’ in relation to your work?

ES: Yes, I call it graft. There is a lot of meaning applied to it, so I thought it was a good name for the project. It also can refer to the graft of the skin, you know. So there are all kinds of meaning that are applied to it.

CN: At your artist talk, you mentioned these patterns in your work coming from reja designs?

ES: Reja is fence in Spanish. It is the proper name, because maybe a fence will look like all different things. However, reja will be the raw item of fence. The design used in Screenhouse was based on Puerto Rican rejas.

CN: At your artist talk, you explained how you invited artists and writers to create a book in relation to your work that local organization Sector 2337 published.

ES: Yes, Sector 2337 made a publication in the form of a newspaper—we worked together on this project. So what happened was I had an exhibition scheduled in NYC at a place called Cuchifritos, which is a really awesome place in the Lower East Side by the S.S. Market—and it’s a huge market. Imagine this amazing market that has food everywhere, but it also has a contemporary art gallery right there.

CN: That sounds great!

ES: It’s incredible, and if you’re artist you’re like, “Oh my God, how can I be a part of this?” So I saw it around 15 years ago, and I was like, I really want to show there someday. I got rejected a couple of times, and after a while I finally had the right project. What I offered to do was cover one side of the gallery with one of the rejas, the graft, and then provide a sitting area, and what I did in the sitting area was create a representation of public bus stops. They were a very minimal-looking representation based on a design from a bus stop in Puerto Rico. Then next to it, I had this newspaper dispenser and they had the publication, which had contributions from architects, political writers—I had a writer that wrote a piece about Puerto Rico and the fences, the rejas. It’s beautiful. We put together a second publication that was in the show at Sector 2337. The show travelled from NYC to Chicago and in that second iteration we had a second newspaper, which also had contributions by artists, poets, etc. We also had a fictional story included–we were trying to create a new history for the patterns. I did this in the same manner in which my work brings people together. How do we bring different people from different disciplines to write about something? I might not be an expert on architecture, I might not be an expert on fiction, but I bring in people that are and we work together.

CN: That sounds amazing. Sector 2337 is such a cool space.

ES: It’s so great. The owner is Caroline Picard—she’s fantastic. She’s been doing her publishing, which is Green Lantern Press, for a long, long time.

CN: Is the newspaper you mentioned available at Sector 2337?

ES: She probably has some, yes. She might have both of them.

CN: Earlier we were talking about you as an archaeologist finding these bottles, and you mentioned relating it to Puerto Rico—

ES: Yes. It is similar to when I used to find shells on the beach there. That was actually something a friend of mine pointed out. She’s a curator; her name is Ruslana Lichtzier. She was the one that said, “Edra, what you’re doing in your neighborhood is exactly like what you would be doing if you were on the beach collecting shells.” And I thought, oh my God that is so brilliant, because I know the parallels—the connections between the bottles and the shells, you know? It makes sense to me to pair them as a material: the glass being made out of sand, the chemistry of making glass bottles. So that makes the shell compatible to the glass as an object, it makes it a good pairing. But the shell is also a house for an organism. How do you make a new house for that substance; a new house for a new home? The project is also trying to put that object in your hands. I’m trying to give you this object that I found. I’m giving it to you as a piece of American history. So there are all these things that I’m trying to convey through Open 24 Hours.

CN: Before your friend mentioned this, had you been using shells in your artwork?

ES: Actually, we talked about this very early on. I started officially collecting for this the project at the end of 2016, and I talked to her about it. When I tell her the story, she told me this, and I thought, that is a great way of thinking about it, because that is something that I am always try to bring together in my work—

CN: Puerto Rican and American culture—

ES: Yeah. I’m always trying to show that relationship between Puerto Rico and the U.S.

CN: That’s such an interesting parallel. It’s interesting what people choose to collect, and, throughout history, what gets deemed valuable enough to be collected. I love that you are taking garbage, a substance that is not considered to be valuable anymore, and then making it valuable again by changing its context. In a way, you are creating your own historical record. Historians may say, ‘Oh, this is important culturally,’ but a lot of times certain demographics, histories, or neighborhoods get left behind; marginalized voices and cultures are forgotten. So you are taking this neighborhood’s history that people might not know about and you’re recording its history, which is incredibly important.

ES: Garfield Park is an important neighborhood in Chicago—it’s very interesting to learn about the history of that neighborhood in particular. I think it’s what makes it complicated. Chicago is a grid and it is so clearly divided from place to place. And then you have ignorance combined with word of mouth, you know, don’t go here, don’t go there—it immediately becomes these divides. What started happening in Garfield Park is that artists start moving and have studios there—

CN: Because it’s cheap.

ES: Yes.

CN: That’s what always happens.

ES: Artists are always the troublemakers! Because they know good, and everyone else knows what is good through the artists. All the developers are following the artists. So we have to keep it quiet! But yeah, that’s how it happened, I think. It’s, like, they know it’s cheap.

CN: And then they tend to also make it—

ES: Trendy! [Laughs]

CN: It’s so interesting that you’ve lived about half of your life in Puerto Rico and the other in the U.S.—almost exactly half and half now.

ES: It’s almost there!

CN: I feel like the first 20-25 years of your life are so formative—they seem so long.

ES: They were important to me, too. I was around 25 or 26 the first time I left Puerto Rico. I left because I got a fellowship in Paris for painters. I lived there for a year. I didn’t even leave Puerto Rico to come to Chicago; I left at first for Europe. Then I travelled a lot, which really changed my perspective, and went back to Puerto Rico Then I came to Chicago.

CN: So the first place you went in the US was Chicago?

ES: Yes.

CN: It must have really won you over.

ES: Yes, immediately! Although, it is terribly cold. Freezing. I’m like, how do people live like this? But it’s so special. I love it.

CN: Definitely. I didn’t realize until moving here that there is such a large Puerto Rican community.

ES: It’s true, it is very prominent here, but it is a different kind of Puerto Rican community. It’s not like where I’m from because I didn’t grow up in Chicago like they did, I grew up on an island. It is a very different experience. I will always find culture here, which, as an artist, is what I am craving. I mean, in Chicago it is everywhere. There is so much cultural activity, I find it impossible to leave here.

CN: I’ve been living in pretty large, diverse cities for the last year or two, and I always get this amazing sense that because everyone is from somewhere else, in a way, everyone belongs.

ES: Yes, it’s a melting pot. For me, this is something that you have to purposely try to engage in your own work. How are you going to create a kind of work that isn’t difficult for every kind of people; how can it be inclusive?

CN: So when you moved here, was it for school?

ES: Yes, for grad school. I went to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. I’ve been working there for about four years now. I didn’t work this year, because I’ve been travelling all year, but I’m going back in January. I’m teaching part-time for the contemporary practices department. I’ll be teaching a research course. I teach what I preach!

CN: That’s amazing! Those kind of theoretical classes were my favorite.

ES: It’s really fun! You really learn how to find context, find the complexity of what you’re making, find the root–the where and why, you know? I think that is so important and I think sometimes people are not really thinking about this. Especially students. They can be very impulsive and spontaneous, but to find your direction, your focus—it is really fun to be helpful about to provide that.

CN: I bet you have so much fun in your class.

ES: I make it so I can have fun, too. I usually organize and design a semester that has a good variety of things for us to do. I want students to feel that they are learning how to communicate about their work, which is something that can be pretty challenging. Finding strategies—how can we do that? How can we figure out how to communicate alternatives, you know?

CN: I think it’s really hard, especially when you’re developing your body of work, to be able to articulate what you’re trying to do when you’re just figuring it out.

ES: Yeah. The other thing that is great about it is that I try not to marry to one format. There are so many ways that something can manifest, or how to frame what you want to do or say. There are so many options. I’m finding that out—I’m finding the best option. So that’s really fun, because it’s not about making cake.

CN: Yeah! There’s not one way to do it, there are so many different avenues.

ES: Yeah, there are so many ways to do it.

CN: I have to mention that at your artist talk you had this really great line that I want to quote. You were talking about community and inclusivity along with these spaces you’re creating, how important they are. You asked, “How can we celebrate our existence?” I just thought that was such a simple and powerful quote. Do you have anything else to say in regard to that?

ES: Well, I think having an artistic license, you know, you are giving yourself permission to reach impossible subjects. Like, it can be as absurd or ridiculous as you want but it can also be very meaningful. And that’s what makes art language perhaps one of the most powerful languages, right? Music can be very, very powerful as well because you don’t have to understand anything. The rhythm will get inside of you and you can do nothing about it. Art has that power of just stripping everything away. This is how you get together. This is how you can have an experience. It can be completely visual. I do care so much about the meaning of things. I want to understand the world and I think my work is the result of how I understand the world. Its hard to exist, anyways, you have to find a way of coping with that as well.

Featured Image: This image shows a detail shot of Soto’s installation “Open 24 Hours” in the Commons at the MCA. There is a white shelf structure with intricately cut designs that hold brown, green, and clear empty liquor bottles that are decorated with white shells. Image courtesy of the artist.

Christina Nafziger is a freelance writer with a background working in curation, arts administration, and community outreach. Originally from Indianapolis, she recently earned an M.A. in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths University of London. Her area of research focuses on gender studies, performativity, virtual identity, and cyborg culture.

Christina Nafziger is a freelance writer with a background working in curation, arts administration, and community outreach. Originally from Indianapolis, she recently earned an M.A. in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths University of London. Her area of research focuses on gender studies, performativity, virtual identity, and cyborg culture.