This interview is a collaboration between Sixty and Chicago Home Theater Festival, a festival that invites strangers into each other’s homes to share a communal meal, experience transformative art, and build intentional community across lines of difference. CHTF centers the leadership of women and femmes, artists of color, immigrants and refugees, LGBTQ folks, and artists with disabilities whose creative practice disrupts injustice and paves cultural safe passages across our hyper-segregated city.

Prior to the festival night on May 18th that he is hosting alongside Bernardine Dohrn, writer Michael Workman sat down with professor, revolutionary, and agitator Bill Ayers to discuss how he came to host of a production in the Chicago Home Theatre Festival, working with children, and much more.

Michael Workman: Where do you live?

Bill Ayers: We moved to Chicago from New York with three young children when I took a faculty position at the University of Illinois at Chicago in 1987. My partner had attended college at the University of Chicago, and had graduated from the Law School there twenty years earlier—she only wanted to live in Hyde Park, and we looked no further.

MW: What’s changed about your neighborhood? What’s stayed the same?

BA: It seems pretty stable—of course it’s become more expensive in 30 years, but Valois is still on 53rd Street, and Seminary Coop/57th St. Bookstore is still the best destination book store in the city, a spot where folks from every imaginable background meet face to face and make the magic.

MW: What do you think people assume about your neighborhood?

BA: Different people undoubtedly assume different things. Over the years our neighbors have included firefighters and teachers, students and professors, artists and musicians, cops and bus drivers as well as Gwendolyn Brooks, Harold Washington, Muhammed Ali, Quentin Young, Rashid Khalidi, and Carole Travis; today we have Louis Farrakhan, Rosellen Brown, Tim Black, Sara Paretsky, and Barack Obama. Good company.

MW: What do you want people to know about it?

BA: It’s at the crossroads of chaos and opportunity.

MW: What’s a person or place that is quintessential to this community?

BA: Farmer’s Field, where the only racially integrated little league in the city assembles and plays every Spring afternoon.

MW: …We’re here to talk, in part, about your involvement in the Home Theater Festival.

BA: I’ve been in it since the beginning, I was in the initial class. I hang out in a couple of overlapping spheres. Okay. This is Albert Parsons: “Will I be allowed to speak, O men of America? Let me speak, sheriff Matson. Let the voice of the people be heard.” But yes…the Home Theater Festival. I got involved because, in my overlapping worlds in Chicago, well, there may be 3 overlapping worlds that are relevant. I think the most relevant thing is I’m a father and a grandfather and very involved in a lot of kid’s stuff, so I did a lot of kid’s theatre. But I’m involved in—as an academic at the University of Illinois at Chicago for a long time—I’m a lifelong activist, peace and justice person and then the arts have always been important to me and more so I think since I’ve been in Chicago. More active engagement, not as an artist, but as an admirer of the arts. So last night I was a judge and have been since the very beginning of Louder Than a Bomb, since the very first competition. Why am I a judge? The reason is because I admire the culture [of slam poetry] so much, but am not of the culture, and if you’re of the culture, you’re less good at some level because people are kind of looking at you like you have skin in the game.

MW: So this whole experience of children, that’s been hugely influential on your interest in theatre.

BA: Right? You know this, what they get interested in then has a huge influence on what you’re interested in and I was an early childhood teacher so stories and drama were always a part of it. But I think coming to Chicago I just had these overlapping circles. So how did I find the Home Theater Festival? Some people around the Jane Addams Hull House were the ones putting it together. Irina [Zadov] and others, they said to me, Hey, we’re doing this crazy thing that started in California, theater in a home. Would you like to do it?” and I thought the idea was thrilling. I loved the idea just on the face of it and then I did it and every time we’ve done it it’s gotten more interesting. More fleshed-out and pushed out and the last few years have been absolutely magical. We love having our house be a public space anyway, we do a lot of conversations, fundraisers, gatherings. It’s a Hyde Park house so it can accommodate a lot and we’ve had some pretty historic meetings there now that I think about it. So when they approached us, I thought “Sure!” I’m used to making dinner for my students for seminars, for gatherings, so the idea of putting out food for 60 seemed kind of fun. As many years as its been going on, in the last 3 years my son, who’s a very accomplished playwright and a professor at Northwestern—Zayd for the last 3 years has had a play at our house, so he’s been willing to let the CHTF use his plays. A couple of years ago, he had a play that was commissioned by the American Theatre Company, they had 25 playwrights and they had 25 years, and they gave them each a year and they had to write a 5-minute play with music for that year. And Zayd was given 1989, so of course the soundtrack of his play was Public Enemy’s Do the Right Thing and the play itself, in terms of its performance—I’ve seen it before at ATC—but at our house, the play took place on our front steps. One of the things about home theater is you go on a tour of the neighborhood with a tour guide and then you return to the home. As the folks were returning to the home, unbeknownst to them, the play was being performed, and it drew our attention but it actually just seemed like a couple talking.

MW: So this is the audience’s first encounter of it.

BA: Right, it’s their first encounter of it. You don’t know anything, that it’s a play. You come back to our house, whatever it is, 45 or 60 people, they get herded back to our house and sitting on the front steps next to us, really close because we live in this kind of row house is this African American couple, and they’re having an argument and you’re drawn to it because it’s both an argument and a seduction and you can’t quite make it out but they’re arguing because they’d just seen Do The Right Thing and they’re debating whether it was any good and what it meant. And as the play evolves you realize, I mean there’s a seduction part of it in the sense that he says to her “I didn’t know this was a date, I thought I was just taking out my mentor at the law firm,” and she says “Well, if it wasn’t a date, why’d you put your hand on my leg?” and you know, blah blah blah this is all going on and she’s taking the position that Malcolm is right in the Do The Right Thing scenario and he’s taking the position that King is right and they’re having this debate and there’s a little bit of action I won’t bother you with but you slowly realize that it’s Barack and Michelle’s first date. And it’s true. That was their first date they went to see Do The Right Thing right in our neighborhood.

MW: That’s hilarious. It’s a micro-play about their first date.

BA: It’s adorable. And then last year, we have in our house off the living room, we used to have a storage space but we converted it when our granddaughters got a little older, we converted it into a playroom. So it’s under the front stairs is a little playroom and Zayd had done a play in New York that got a lot of attention; a set designer named Christine Jones, who’s a Tony award winner, she’s received lots of theatre awards and she put together a piece called Theatre For One in Times Square, which was a peep show booth. She put together a peep show booth, like a pornographic booth and it sits in Times Square and one actor and one audience member come in and the screen goes up and the actor performs the play. So Zayd had written I think 3 plays for that series and it really got a lot of buzz in New York because it’s such a powerful idea and they had some interesting actors doing it one audience member at a time. So we did that play in our playroom. We had one actor in our playroom sitting on a chair and one audience member at a time would go in. So I’ve been thrilled about the fact that we can have our house be a venue not only for art and community-building, and this something special about Chicago, but also that Zayd could play a role in it. It’s pretty cool.

MW: Bringing all the points of contact together. Yes, there’s this whole movement now in immersive theatre where people are trying to put people directly into these experiential environments. There was a play in Chicago called “Learning Curve” put on by the Albany Park Theater Project. It had come out of this group called the Third Rail in Brooklyn, with the Goodman. I know about it from Anders Lemus-Spont who I think was the set designer on the project, and who’s married to Marya Spont-Lemus and mutual friends with my partner Naomi Miller from when they both worked together at PlaceLab, right next door to where we’re sitting here at the Exchange Cafe. It was a day in the life of a CPS student. They got use of an abandoned Catholic school, which I thought was pretty great and put you through what the experience was like as a student, walking through the space with metal detectors and this kind of stuff—

BA: Awesome!

MW: Right! What bags you can carry and not, and just the paranoiac reality of the public school system at this point.

BA: You know, Zayd had a play in New York at PS1, which is a former public school that’s called Public Space 1, an art space and they have several playwrights again and the audience, you would come in at 15-minute intervals and the audience would go to one classroom and then move to another classroom and then another classroom and the play would be going on in the classroom. Zayd’s play was called something like “Sex Ed” and it was a 7th-grade classroom and you stepped in and one of the audience members stepped out and she was a parent who was having a parent conference with the 7th grade teacher. She’s a beautiful, young mother and the teacher is a guy. She begins to ask him about how he teaches science and how he teaches Sex Ed and it becomes more and more fraught because he’s trying to be honest and smart with the kids and she’s a little bit skeptical that learning, at the age of 12 or 13, in a class where they’re discussing this stuff. And on the desk he’s got a box that says “ask the sexpert,” and Zayd took that from his little brother Malik, who’s a science teacher in Oakland and does that when he teaches Sex Ed, “ask the sexpert.” And the questions you get when you ask a group of 12-year olds to just anonymously ask you questions—

MW: Man, they’re probably off the hook.

BA: Fucking crazy. So Zayd uses some real-life things from his brother like, “If you sleep with a girl can she become pregnant?” That’s the kind of question. Or, “can you get pregnant with oral sex?” And the mother, the more she hears about what’s coming out of the “ask the sexpert” box, the more they end up kind of flirting with each other. It’s adorable. I love those kind of public spaces when they’re converted into this immersive theatre, that’s great. And also, of course, from my generation, the Living Theatre, Judith Malina and Julien Beck was a very important kind of immersive theatre experience.

MW: And I think that history is fascinating and also, as you mention, this connection now here to Chicago. I’m working and thinking more from the social practice side and there’s this long history in Chicago, going back at least a century, tied up with the history of the avant-garde, of art in this city that attempts to engage socially in a way that it perhaps doesn’t in other places. But that’s a whole other conversation.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

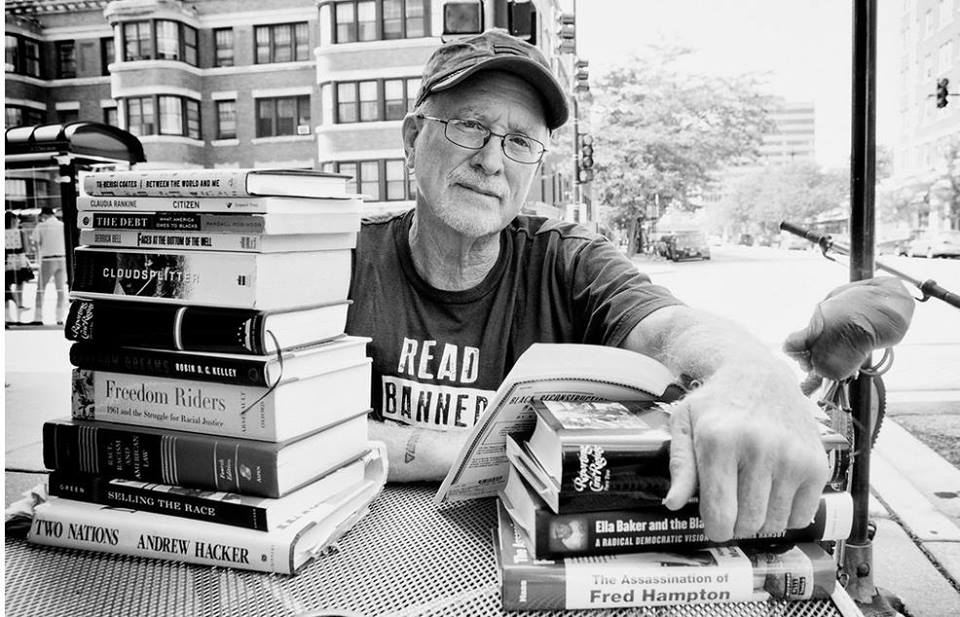

Featured image courtesy of Bill Ayers.

Michael Workman is an artist, writer, dance, performance art and sociocultural critic, theorist, dramaturge, choreographer, reporter, poet, novelist and curator of numerous art, literary and theatrical productions over the years. In addition to his work at The Guardian US, Newcity, Sixty and elsewhere, Workman has also served as a reporter for WBEZ Chicago Public Radio, and as Chicago correspondent for Italian art magazine Flash Art. He is also Director of Bridge, a Chicago-based 501c(3) publishing and programming organization. You can follow his daily antics on Facebook.

Michael Workman is an artist, writer, dance, performance art and sociocultural critic, theorist, dramaturge, choreographer, reporter, poet, novelist and curator of numerous art, literary and theatrical productions over the years. In addition to his work at The Guardian US, Newcity, Sixty and elsewhere, Workman has also served as a reporter for WBEZ Chicago Public Radio, and as Chicago correspondent for Italian art magazine Flash Art. He is also Director of Bridge, a Chicago-based 501c(3) publishing and programming organization. You can follow his daily antics on Facebook.