The Chicago Archives + Artists Project (CA+AP) is an initiative that highlights Chicago archives and special collections that give space to voices on the margins of history. Led by Chicago-based writers and artists, the project explores archives across the city via online features, a series of public programs and new commissioned artwork by Chicago artists. For 2018, the Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation has funded a series of pilot projects pairing three artists with three archives around the city: Media Burn + Ivan LOZANO, the Leather Archives & Museum + Aay Preston-Myint, and the Newberry Library’s Chicago Protest Collection + H. Melt. This series of articles will profile these featured archives and artists over the course of their collaboration, exploring the vital role of the archive in preserving and interpreting the stories of our city as well as the ways in which they can be a resource for creatives in the community.

In this segment, I sit down with Ivan LOZANO in his studio to discuss his experience working with Media Burn Archive, the work he has been creating influenced by these materials, and the continuous, deep-rooted relationship his practice has with archives.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Christina Nafziger: Have you ever worked with archives before? What has your experience been with archives in the past? Has your experience with Media Burn changed your perspective on working with archives?

Ivan LOZANO: Yeah, I’ve been working with archives for a really long time in a lot of different ways. I think that my work has always been related to archives. When I first started making work that I felt was quote-unquote “real” work — you know, when you’re for-real invested in the work and really doing it on your own — I was fully immersed in film and video, especially in experimental video and non-narrative stuff. I was also really interested in the internet, and I am still super obsessed with it. I sort of feel that everything I do is sci-fi or cyberpunk or something. When I first started making work, I was downloading old films from peer-to-peer networks.

At that point, I was working with vintage gay porn films that I was finding online. I was really interested in it because those films and archives were the only way I had to reach back to these generations of gay men that had all died because of AIDS. At that time, because of oppression, the only cultural production of theirs that was still alive was either disco music or gay porn. I was interested in these links and how, through these peer-to-peer networks, I could type some commands on my computer, and then the computer would take that and pull this information out of thin air — it would find these ghosts that were floating around of these people. It was sort of like this séance. I was getting back to these traces of these humans that I would never have access to — these traces of cultural production and things that really marked their life.

CN: That’s really interesting! After looking at your work online, I feel like it’s almost like you’re re-materializing these people and their identities through this imagery in your work. It makes complete sense that you would work with Media Burn. It’s a perfect fit, even in regards to materials. You use packing tape in you work, which has similar properties to the tape in a video. In your process, are you transferring images onto the packing tape?

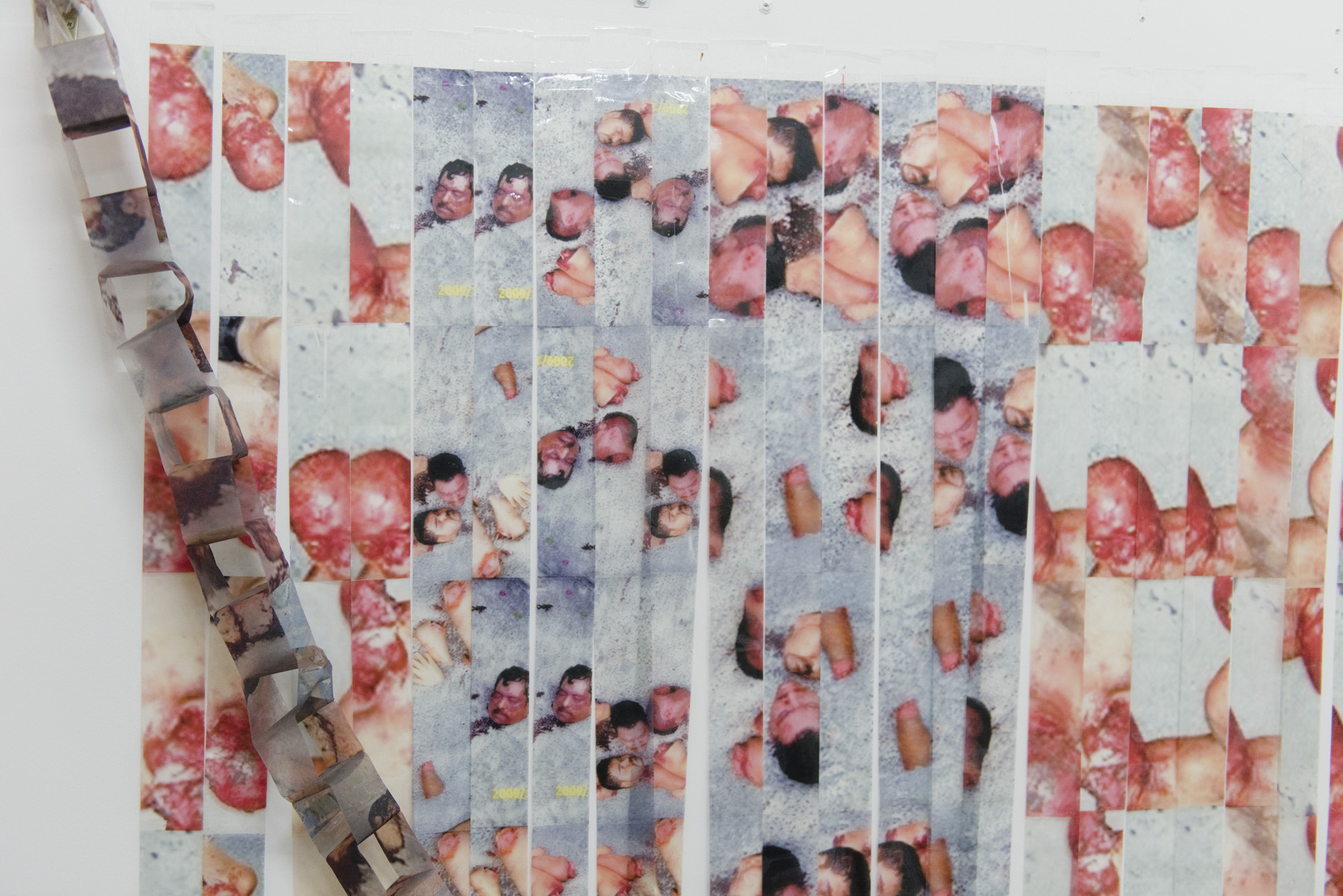

IL: Yeah. In this example, [points to materials set on table] I printed all of the images — one frame per second — of an 18-minute-long video. Then, I press these tape-strips on each printed image, and the image gets transferred onto the tape. I sort of consider Google as another informal archive [when gathering imagery]. I am of the generation that really had one foot in the analog world and one foot in the digital world. So I have had a Google algorithm, basically, since Google started. I see Google as a kind of collaborator, and I tie that to conceptual theories; I consider it an active participant in my work. My algorithm is going to be different than yours, so in some ways my search terms and results, or those images, are going to be tailored to me. But they’re also going to be responsive to the things that are going to be interesting to me already. So it’s a way for me to focus my content. That computer language is like a spell that a third-party understands and then translates. There’s still this idea of spirits on the internet or beings on it.

CN: You said you were really into sci-fi?

IL: Absolutely. I’m also interested in cyborg theory and transhumanism. Philip K. Dick was another one of my huge idols—and philosophers. I was reading this Jean Baudrillard book called “The Transparency of Evil” and I felt like it was just talking about social media, specifically Instagram, and how people deal with Instagram stories.

CN: Yeah! One of your exhibition titles reminds me of that. What was it called?

IL: The exhibition was called “THE TRANSPARENCY OF EVIL” at South of the Tracks Projects, and it was a two-person show with Kate Hampel, curated by Scott Hunter.

CN: You discussed that you use algorithms in Google that have been created by straight white men. You’re pulling images and imagery from there, so do you think that it’s inevitably shaping what you’re finding, in a way?

IL: Yeah. A difference there, though, is that I also introduce a lot of noise to it. I go in really deep dives into Google image search so that there is so much garbage in my algorithm. There are so many crazy searches. I was trying to break it or see if I could force it into submission or something. I think that’s sort of a similar way of how I think about appropriation — I’m appropriating the tools, and the images are symptoms of the tools, in a way. I’m just trying to sort of sabotage them. Also, relating this to the history of photography and the idea of truth — truth isn’t real anymore. That’s something that, in my work, I’ve been sort of freaking out about! We don’t have truth anymore. We don’t understand how the tools have changed society.

CN: It’s moved and progressed and advanced so fast that …

IL: … We haven’t caught up. A quote by William Gibson that I quote all the time is, “The future’s already here, it’s just not evenly distributed.” We’re living in a William Gibson, Philip K. Dick world where we’re still thinking this idea that, “a picture is worth a thousand words” or that there’s an objective truth or something. And there isn’t.

CN: We’re so far past it. I mean, was there ever a truth in an image? It always makes me think of it in terms of social media, and how it’s not just one photo. Which is why I love your work. It’s not just a single photo — It’s multiple pieces of a single photo or a frame. It just reminds me of these false-built narratives through social media, through these image collections online.

IL: Yeah. There’s a media theorist Lev Manovich that writes about this; he calls it the database logic. That’s basically how, as humans, we sort of navigate a database. Our brains will try to find a pattern or a narrative to it. So because I feel like I can lean a little bit on the Google algorithm, a huge part of how my work comes together is that chance operation of having these things printed out, and trying to find how the images fit together. Whether it’s formally by cutting the images up and weaving them, or by color or line. Your brain tries to make sense of patterns and repeating lines — it fills in a lot.

CN: If you were to put the images in your work in a linear line, it would be like creating this false sense of order just to try to make sense of it. It reminds me of how — in science fiction, especially in Philip K. Dick short stories — people are constantly trying to predict what’s happening, and science fiction itself is trying to predict the future in a way. In present day, we also try to do that and prepare, but we have no idea.

IL: Yeah! In literary theory, a lot of discussions around science fiction isn’t about the future. It’s really about the present, and dealing with things in the present that maybe we don’t have the vocabulary to explain. But another thing that science fiction does that’s really fascinating to me is that these writers — through this creative process — these artists get to craft something. This sort of potential.

CN: I love your use of the word “imprint” on your website. You use it repeatedly. You mentioned your Mexican Catholic upbringing and how all of this had an imprint on you. Then, you’re making these physical imprints — from imprints online of these other parts of your culture that you’re trying to reach. Then, you’re taking these imprints — these videos — from Media Burn archive. So my question is, what is the imprint you are trying to create?

IL: I started getting really committed to this process with the transparencies on packing tape. One of the reasons that I started working outside of computers and in a physical realm was because people don’t understand how digital technologies work. They don’t understand the amount of labor and care that I had to take when I was working on these videos or digital files. This labor was invisible. Technology right now is trying to be this black box — this closed system where users can’t really touch it. Again, going back to this specific moment in human history that I grew up, I learned to code — or at least HTML — by trying to create avatars for myself on chat rooms.

CN: That’s so interesting because, at the time you were trying to do that, it was probably even more limiting. The technology only had progressed so far, so you were using these limited platforms. It’s almost like even now using Photoshop, you can create anything you want within that program, within those parameters.

IL: I’m trying to get away from those parameters, because I think that the rate at which tools are developing right now means that there’s not enough time for artists to really learn how to break the tool and expose the limits of it. I think that a lot of times art functions like a defense mechanism, or like white blood cells. To understand the ethics of the technology, the limits of it, we try to break it, try to reuse it. In the beginning of the experimental avant-garde, there was that idea of breaking technology — whether it was photography or sound recording technologies. Artists are the ones who always end up figuring out how to use it. Without artists, photography would not be what it is today — and we would not be living in an image-saturated culture! Artists are the ones who are going to do that with the internet, but tools are moving so quickly that I felt like I didn’t have the time to keep up with the tools of the computers. I stopped doing that when Final Cut sort of refreshed the way that their interface worked and changed everything. And I just decided, “You know what? This is a sign. I need to get away from this.”

CN: Is that when you were working mostly in video? I’ve spent a lot of time on your website today — it’s like a black hole of information, which I love. There is just so much on your site: video, installation, and then there’s your “IMAGE FILE PRESS.” And I love your studio journal because it is kind of like your Instagram, but it is its own thing. I thought, “Oh, cool! This is literally his own archive.” He’s archiving his own work.

IL: Yeah. But also, I’m archiving my influences. I’m saving all of it.

CN: It’s so smart. And, not only that, you are making it accessible to anyone, which is amazing. So you work in collage, sculpture, installation, video — and although you don’t primarily work in video currently, there was a video from this year, right?

IL: Oh! “ANDACHTSBILDER.” That was an interesting experience because that was the first time I was asked to put up a piece that I had done a long time ago. So, that was version three. The Andachtsbilder is a German term referring to religious sculpture that is meant to impart a moral message. A pieta is a perfect example of it. I wanted to use that term as a way to focus a spell. There’s this one artist, Steve Reinke, and in the video of his, he talks about this potential future where there are security cameras everywhere recording everything all at once. So then the value of the camera or the image has more to do with its placement than it does with the thing that it is representing. So, in this case, this term is used as a sort of generative word, whereas, before, it might have been a word that describes something. This was the third time that it was shown. Every time that I’ve done it, it has responded to the technology that was available in the gallery or in the space. So it’s also a really stressful process, because I didn’t know what kind of projector I was going to get or use. I didn’t know what the space was going to be like.

CN: That’s so stressful. Can you describe what the video is?

IL: Yeah! So there is no video. In the first iteration I was using the colored lights that monitors use, and refracted that light. The second one was at The Sullivan Galleries at a show called “The Great Refusal,” which was curated by Oli Rodriguez. I had a really cool, really good projector that took all these different formats. And one of the things that projector did is, if you set it to just go and had no source connected to it, it would just cycle through the different video profiles. That meant that, you wouldn’t be able to notice it, but that white light that it projected kept flickering and changing as it kept trying to read a non-existing source.

CN: Whoa. That’s really cool.

IL: Yeah, it’s what I was talking about — the white blood cells of new technologies. What are the limits and how do we interact with these objects? So in this situation — I had no idea what the projector was going to do. This was at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art in a show called “HAPTIC TACTICS” curated by Risa Puleo, Noam Parnes, and Daniel Sander. This projector had something called a “learning mode,” which was just this beautiful grid that I was able to then project and use as the content of the video. So I’m exteriorizing the idea of the image and the file. Because, in the end, when you have a video file, it’s just code that a computer reads. Then, our brains make it into an image that we can then read. So, in this case, there was no information — there was no movie file. But still there was this image that the projector was creating. There’s that exteriorizing of the content outside of the piece of technology that I think animates a lot of my work right now — that transparency of taking the object outside and trying to just play with the image instead of the data, and cutting and making it tangible, so that we can mess with it.

CN: Yeah, like a conjuring.

IL: Yeah, it was like a séance. It was calling, so it was a conjuring. Relating this to the term magick with a “k,” which is different from stage magic — it’s that process of divination, of staring into a crystal ball, or a dark mirror or something. The whole point is to stare past the image, basically, into your own interior self — to try to find the patterns and figure out that concept. Your intuition is supposed to guide you there. So it’s this sort of trance state — and trance state is something that’s really interesting to me in general as well.

CN: Yeah. Earlier you referred to the internet as a black box, discussing when you were doing a lot of labor digitally that was behind the scenes. It’s interesting because your work transfers that labor physically into these materials, transferring that value of labor and how people see it. It is like you are transferring a value in a way.

IL: Yeah. That’s an important one because I am. When I am working with images of murder in my work, images of the Narco murders, I am the person who has spent the most time with those images, probably, because I would spend hundreds of hours, touching the image, literally rubbing it. It’s an image that serves a purpose; it sends a message to other people, but it’s an image that people recoil from. It’s a difficult, painful image and topic. It’s impossible for me to find who the people in the images were and give them that care. So, going back to that monastic shamanic thing, I’m literally touching the image, thinking about them, and rubbing them, trying to break them into something different. I’m trying to sabotage the work that the image is supposed to do. There’s something about spending that time and touching the images and–

CN: There’s that ritualistic, repetitive aspect.

IL: Yeah. During the process, I place the packing tape on the image, take it off, then just dump it in water. Then, when the adhesive gets wet and loses tackiness, I can just rub off all the cellulose and the ink stays on the paper. So it ends up being me sitting with a bowl of water and just touching the images, rubbing them for hours and hours — like a rosary, basically. And relating it back to trying to identifying patterns — those old religions set those patterns. Now what do I do with these images? How do I make them alive for now? How do I care for that process?

CN: Does your interest with those traditions come from personal histories or just a personal interest?

IL: It definitely comes from family history. I grew up in Mexico, in Guadalajara, and most of my formative aesthetic experiences were always around either churches or markets, so it was either this artisanal experience or how people operate in churches, and how that art works. It’s always colorful, there’s always a little bit too much feeling — too much in the imagery. Everything is bleeding and in pain. The visual culture in Mexico is turned up. And I was exposed to a lot of it!

When I grew up in Mexico, it seemed like the past just kept creeping up on you in different ways. So there would be old traditions that would come forth. Just like how I use early gay pornography as a way to sort of reach out to these groups of people that I won’t be able to meet in person, in this way I am trying to reach out to my ancestors. I’m trying to tease those things out, these traces of those histories. Information is still something that’s alive, and culture is something that’s alive. It keeps changing, and evolves, and that evolution is sometimes like a metamorphosis, and it might be really violent and painful. It definitely is in Mexico, a lot of times. So I’m trying this ‘magickal thinking’ through this process to propel it into the future, assuming that I already know the answers and I just have to get to them.

CN: Yeah. So you are taking all of these bits and pieces of your past, your ancestors, gay culture, taking them all into the future — you want them all to be there and to move forward together.

CN: When you started working with the files at Media Burn, did you have a plan on what you wanted to take away from archive, or what you wanted your work to become using this archive?

IL: I was really excited to work with them because Media Burn also comes from the history of experiments in media and video-making — even in the name, which references Ant Farm. A lot of the early stuff they did is still really unbelievable when you really read what they did and how they were thinking about media. So I was already just excited to work with a place that was definitely a part of this history that I know really well. I’m obsessed with the history of video making and video as an artistic medium. I think a lot my interest in it comes from being able to see a future for myself as a maker in that experimental video world.

IL: At the beginning, video especially was a medium that was very open to people of color, and people of different sexual orientations and different genders. There were a lot of women involved in early video-making. There were a lot of queer people and people of color involved in that history, too. From the beginning there was that idea of appropriation, that this medium was something more than just a tool of representation. It was tied to Fluxus, John Cage, and all of these conceptual thinkers that I’m also invested in. It was tied to Dada and Surrealism and this history of avant-garde practice in Europe, as well. It was about the tool and how we can fuck with it. It was about that process of transubstantiation from one medium to the next and bringing it back. The tools are part of the art-making practice — or the practice is messing with the tools, just like when Nam June Paik used a big magnet on a television set to bend an image. Messing with the representational qualities or representational possibilities of these media, especially in video, was a super important thing from the beginning. So I was glad to fit into that history, somehow, by working with Media Burn. I didn’t know what I was going to do, because I have moved away from moving images so much. I’m not interested in the representational qualities of it. So I was wondering what I was going to do. And, in the end, my first instinct was to try to see if I could find myself in the archive, somehow. I wanted to use the search capability of Media Burn’s website as a collaborator, because it was through Google, in the end.

CN: During the panel you were on at the Chicago Archives + Artists Festvial, I loved that so many people said they wanted to find themselves in the archives. They wanted to see their history, their selves, their identities, within that.

IL: I didn’t know what I was going to find [in the archive.] So I just searched for “Mexican” and saw what they had. One of the things that, as a person with a Mexican background in Chicago, that kept coming up was Pilsen. I’m not from Pilsen, I have nothing to do with Pilsen, I lived there for two years. But that’s not me at all. So the fact that my term, “Mexican” kept bringing up this stuff was sort of reducing all of that to things in Pilsen, people in Pilsen.

CN: Reducing a whole area.

IL: Yeah! Which is understandable based on the type of archive it is. It is sort of Chicago-centric, so it is the place. But it’s something that I realized when looking through it, right? Then, when I was working with Sara Chapman to find things I could look at, the things that kept coming up were interviews with people in Pilsen, or the Yollocalli students — they have such great documentation of projects that they’ve done there. But again, it’s not my history. It’s not me. So then I decided to maybe add “artist” to the term, and I searched for “Mexican artist.” Two videos that came up. There was a video of a festival — that, in the end, was in Pilsen, I think. But what I ended up landing on was this one video that was produced in 1990, I think. The video is called “Mexican Art Gallery.” It’s also in a tape with — because it’s raw camera footage — something else that they called “Green Card Lottery Winner.” It’s the archives of Judith Binder.

In this video, Judith Binder did this sort of person-on-the-street report, and it looks like it’s in L.A. She goes into this pop-up art gallery called The Works Gallery and looks at these objects, and I recognize them immediately as alebrijes, which is a type of Mexican artistic or folk sculpture. The are these sort of fantastical, really bright creatures with spiky parts. She goes in [to the gallery] and starts trying to talk to somebody, and there are all these papier–mâché sculptures of skeletons. They were these cheesy, borderline-stereotypical Mexicanness of Day of the Dead stuff. She goes in and tries to talk to a lady that’s there, and this woman doesn’t speak English. So then this other lady comes barging in — you can tell that she’s the gallerist, it’s this white lady — and she starts talking about what’s going on. And she says, “Yeah, we know this family, we brought them over from Mexico, they’re making this work for us …” And this lady, it comes out, is married to a movie producer or something. So there are all these sculptures that are trying to sort of remake these pictures — you can see one right here. They’re trying to remake behind-the-scenes photos of Charlie Chaplin productions.

IL: So they brought this family over to make this work and to have this pop-up art gallery to sell it. They go into the back room at some point, where there’s the teenager — it’s like three generations of this family — and in the back room this teenager’s making papier–mâché sculptures. And it turns out — this family’s famous for this, they’re great at it. She starts talking about — the white lady, the gallerist — about how, when they make them, they’re brown, but then people prefer them when they’re white, so they end up painting them and there’s all these things this lady keeps saying, and things that keep happening in the video, that were really disgusting to me. It just felt like micro-aggressions or just straight-up racist aggressions. They were basically kind of robbing this family of a lot of their humanity or individuality. But when they’re talking to this teenager in the back that’s making the work, Judith — the videomaker, behind the camera — asks this kid, “How do you like L.A.? Are you enjoying it?” And he says, “I don’t really know, I haven’t left this room.” And they laugh about it — which is horrifying.

CN: He’s just been working?

IL: He’s just been making work, yeah. Yeah, he’s just been in the back room making work for this lady to sell to white people. I started doing a little more research about this show, and this family, and that’s when the project really sort of took off for me. I actually learned a lot of this history. (This goes along with the making invisible the contributions by Mexican people to American culture and just to culture in general through processes of erasure. For example, calling people “workers” or “artisans” instead of “artists” and “creators,” and robbing them of their identity in doing so.) This family in the video is called the Linares family. Pedro Linares, the grandfather, is famous because he was the inventor of alebrijes. Since the beginning of the 1900s, this family has been one of the main artisan families in Mexico and have invented entire strains of artistic production there.

CN: Wow!

IL: Yeah. Pedro Linares started making alebrijes out of copal wood, which is also a wood that used for incense of indigenous people in Mexico. It’s a very oily wood that’s used for religious practices. So it’s this family! Their work is in museums. They had tons of commissions by Diego Rivera and a ton of really famous artists, but because they’re working in this folk tradition, they’re sort of robbed of their history and their identity and their importance. Even in the way that this video — that, for somebody that’s researching, like, the history of Mexican folk art or just art in Mexico and artistic production — is kind of an amazing document, to see how this family was treated in L.A. and how they were brought there to be locked up in a room to make work about Charlie Chaplin, which this rich producer lady like made them do. And, you know, there’s no tag for Linares, there’s no tag for alebrijes in it. These things were not deemed important in the archiving of this video. However, I’m definitely not putting it on Media Burn — how are they going to know? They don’t have time to do research on every single tape. So I was sort of lucky enough that, through these search terms, I found something that really related a lot to how I’m trying to make artisanal work for this time, in the way that Pedro Linares invented this form. Because in the history of alebrijes and everything — because he was a cultural worker making artisanal crafts in Mexico — he never got a patent on any of this. And it’s like, and now alebrijes is like, basically, if you look at, like, Coco, by Pixar? All of the animals are alebrijes. That’s what they look like. That dog, in Coco? That’s an alebrije.

CN: Mmm-hmm. So with this video, and through your research, or through your experience with the archive, did it influence any of your work?

IL: So this video is about 18 minutes or so. Before, I was just printing one image and then printing hundreds of copies of it and then using that to make a chain or a weaving or something else. Now, what I decided to do with this, as a sort of experiment, was to sort of print the timeline, or print key frames, and see what would happen that way. I ended up doing one frame per second of this video …

CN: This still seems like a lot.

IL: I think the total images that I have are like … six hundred and seventy-something? And I’ve processed about a hundred. [laughs] So far. So I wanted to visualize the video and see what would happen. Especially since there isn’t a specific place that this work is going to end up, I saw that as giving me the flexibility to really experiment with what I could do with it. And the first idea is just to print one frame per second, process them in sort of this chain, and the idea would be to sort of expand it — around a room, or an entire wall or something — as these sort of party chains. There are these moments in the video where this white lady’s saying all this stuff that feels very racist — I wanted to print out that text like a timeline in a natural history museum or something. It is showing these moments of pain, this painful speech.

The idea with these also is that, right now they’re in links, but if I undo the link then I’m basically creating this fiber that I can then weave or create different things from. You know, it’s a plastic fiber — it’s a fiber that instead of being dyed with traditional processes it’s dyed with an inkjet printer and digital images. From these materials, I’m making quilts, I’m making rugs. I mean, instead of indigo and cotton I’m using packing tape and a printer — but those are the materials that I have access to. That’s my nature. That’s my environment — that’s the cyberpunk kind of thing.

CN: Yeah. So tell me about “IMAGE FILE PRESS” a bit. It’s such a cool project.

IL: Thank you. So “IMAGE FILE PRESS” is me creating this archive. I ask artists to create work based on digital images that then refer back to digital images. And it’s meant to all live as free, downloadable PDFs, as image files. So I would commission these zines that I would publish as PDFs, and I asked the artists to each pick one image that stayed in their brain for whatever reason and to create responses to it—and I gave them no more prompts than that.

CN: So the artists picked the image.

IL: Yeah, and they made seven responses to it. In the end — and I never said this out loud but I would tell it to the artists — I only asked queer people and people of color to do these. I very specifically — oh, and women, too — I basically just didn’t ask straight, white men. And it wasn’t explained anywhere else, just because I don’t feel like I need to explain why I’m not going to include you. Because you don’t explain why you don’t include me!

CN: It’s an amazing project.

IL: Thank you. So, I wanted to put that online so that, you know, a little gay kid, a little gay Mexican kid of the future, can have this archive and see that, “Oh, there was this entire history of people making shit. Of making amazing work–of my history.

The Chicago Archives + Artists Project (CA+AP) is part of Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art exploring Chicago’s art and design legacy, with presenting partner The Richard H. Driehaus Foundation. The project is funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art and The Richard H. Driehaus Foundation.

Featured Image: Ivan LOZANO in his studio dipping packing tape into a cup of water after adhering an image to the tape. Behind him are various works of his hanging from the wall. Photo by Ryan Edmund Thiel.

Christina Nafziger is a freelance arts writer with a background working in curation, arts administration, and community outreach. Earning her M.A. in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths University of London, her area of research focuses on performativity within the image, virtual identity, and cyborg theory.

Christina Nafziger is a freelance arts writer with a background working in curation, arts administration, and community outreach. Earning her M.A. in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths University of London, her area of research focuses on performativity within the image, virtual identity, and cyborg theory.