Just outside the threshold of the Armstrong Gallery, where most of the work in Boundary Layer is contained, two of Nancy Fewke’s photographs are set apart. To the left hangs an image of a jagged formation, its peak barely cresting above a darkened, hazy atmosphere. The lily pads that float in the lower corner are the only cue to scale—reducing an otherwise mountainous form into a submerged, rotting tree trunk. Such a trick of the eye is more mountain range than can be found in much of the Midwest horizon, which is why, for many years, Laura Primozic (whose sculptures serve as counterpoint to Fewkes’s images) set her sights well beyond the Illinois prairies she calls home, modelling her work instead on the changing glacial landscape. Only recently have her more immediate surroundings come back into focus.

Fewkes’s vision has followed a similar trajectory. She says of their collaboration, “We were both very interested in ecological integrity…bringing awareness to some of the larger global issues that we might speak to on a microcosmic level—on a regional level—something that we could connect to everyday.” For Fewkes, this is Site A—a single spot on the bank of Spring Lake, a backwater meander off of the Illinois River, a place she says “claimed” her as much as she it. Her word choice is deliberate, lending agency to an environment that is no more immune to the effects of human possession than the melting glaciers. The Illinois Department of Natural Resources estimates that half of the state’s river backwaters “have been degraded in some manner by dredging, damming, pollution, siltation or the presence of exotic plants, fishes or mussels.”

After looking between the first two photographs, the titles, differentiated only by integers, come as a revelation. While the murky and shallow water of Site A, Spring Lake 1.16 gives way to a cliff-like figure, Site A, Spring Lake, 10.15 has a taut and frozen surface—a blue brushed with the reflection of ruddy autumn leaves—beneath which the figure all but disappears. The two images are bookends of sorts, their relation defined by the moments between. Although months passed between the capturing of the first two photographs, just one day separates images 11.16 and 11.17 (taken on November 16 and 17 respectively), yet the change in the waters clarity is just as dramatic. In this state of photographic suspension, the environment’s sensitivity to time’s passing, however brief, is revealed in shifting color, texture, and surface. Even when the central figure is almost completely obscured, I study its absence, having joined the photographer in her effort to create a connection with the earth through a shroud that recedes only under sustained attention.

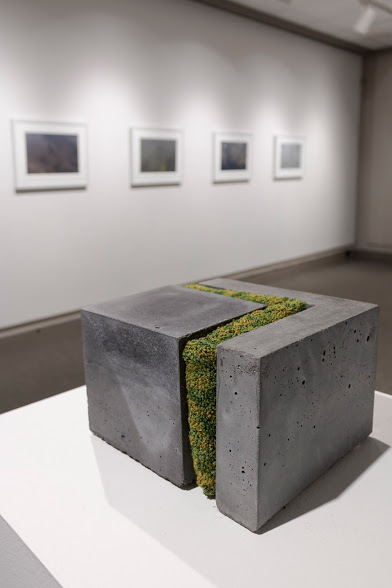

In Laura Primozic’s neighboring sculptures, such attention is rewarded with changes that can be observed in real time. Her exploration is one of material relation—concrete and ceramic against moss and stitched textile. Over the course of the exhibitions month-and-a-half run, the threaded “moss” exists in stasis, maintaining its plush texture and vibrant hues, while the actual moss, lifted from its moist environment, begins to wither. It is easy perhaps to see this contrast as all-encompassing—to set the various material forces in opposition to one another (industrial versus natural, hard versus soft), but Primozic establishes something of a symbiotic relationship between them. In Microenvironments 1, hand-stitched textile fills the gap between two concrete blocks, and a gently sloped earthenware form, suspended in concrete, cradles a small patch of moss in Microenvironments 2.

As Fewkes captures water in its amorphous state, as both a nebulous ether and an impenetrable color field, Primozic works to blur a boundary we often erect ourselves. Even as we overly the landscape with concrete and steel, moss adapts, finds the cracks, sprouts up from the in-betweens. More resourceful still, moss possesses the ability to come back to life, in a sense, after desiccation. Even as a tree trunk rots at the bottom of Spring Lake, drowning in water but unable to drink, moss remains rootless, and therefore survives. It can be taken from its environment, transported to a gallery space and exist for weeks in a microenvironment designed to nourish a higher plane of human need at the expense of its own physiological necessities, and then, in theory, be rehydrated, and reborn.

Since discovering Site A in October of 2015, Fewkes has become immersed in the ecology of Spring Lake. She named the location, which lies at the base of former native habitations, for its history of archaeological excavation over the last century, but it’s the lake’s future that is of more pressing interest. Today, restoration and conservation initiatives are underway along the Illinois River, led by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources. Fewkes recalls her own involvement in these efforts, accompanying a DNR biologist as they collected specimens on a nearby lake. In the micro-environment of Boundary Layer, Fewkes and Primozic suggest that such ecological care can not only reveal the sensitivity of our surroundings, but even has the potential to reanimate a famished landscape.

Featured Image: Nancy Fewkes, Site A, Spring Lake, 1.16 and Site A, Spring Lake, 10.15, archival digital ink jet print. Two images of Spring Lake at different dates are hung on the wall beside the words “Boundary Layer, Photographs by Nancy Fewkes, Sculpture by Laura Primozic.” Image Credit: Lucas Stiegman.

This article is part of Sixty Regional, an ongoing initiative by Chicago-based arts publication Sixty Inches From Center which partners with artists, writers, and artist-run spaces throughout the Midwest and Illinois to highlight the artwork being produced across the region. This work is made possible through the support of Illinois Humanities, which is supported in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Illinois General Assembly through the Illinois Arts Council Agency, as well as by contributions from individuals, foundations, and corporations.

Maggie Morton is an artist, writer, and poet, who earned her BFA in Painting from Illinois State University in 2016. Morton currently lives and works in Normal, IL, where she is the Director and Editor of Sight Specific, an online platform that documents and supports contemporary art programming in the Central Illinois area.

Maggie Morton is an artist, writer, and poet, who earned her BFA in Painting from Illinois State University in 2016. Morton currently lives and works in Normal, IL, where she is the Director and Editor of Sight Specific, an online platform that documents and supports contemporary art programming in the Central Illinois area.