Each December, the New York Times (and likely other media outlets) publish “The Year in Pictures.” For reasons both good and bad, images of Black Americans should predominate in 2020. Some pictures will be tragic, like images of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Jacob Blake, while others will be proud, showing Black Lives Matter protests, Kamala Harris, and Stacey Abrams’ Get Out the Vote efforts. Representations of Black people also predominate at the Art Institute of Chicago in the exhibition Bisa Butler: Portraits. Especially timely today, Butler exclusively presents the Black figure, using personal and historic images as the basis for her portrait quilts.

About her focus on Black people and their narratives, she says:

“I never want my artwork to show my people in a bad light. We are people who’ve come a long way. We do struggle still. There’s still a lot of social ills that are affecting my people, so I want to address that, but I also don’t want this paternalistic view, like ‘oh poor them.’ I’m not interested in that. I’m more interested in seeing ‘look what we can do.’”

Her “look what we can do” shows individual and group triumphs, while also depicting the dignity and calm of everyday activities. While Butler doesn’t cite Kerry James Marshall as a reference, I am reminded of his Mastry exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in 2016, which also foregrounded the Black figure in a grand scale typically reserved for Old Masters. Marshall said he aimed to establish the “black mundane” as a worthwhile genre.

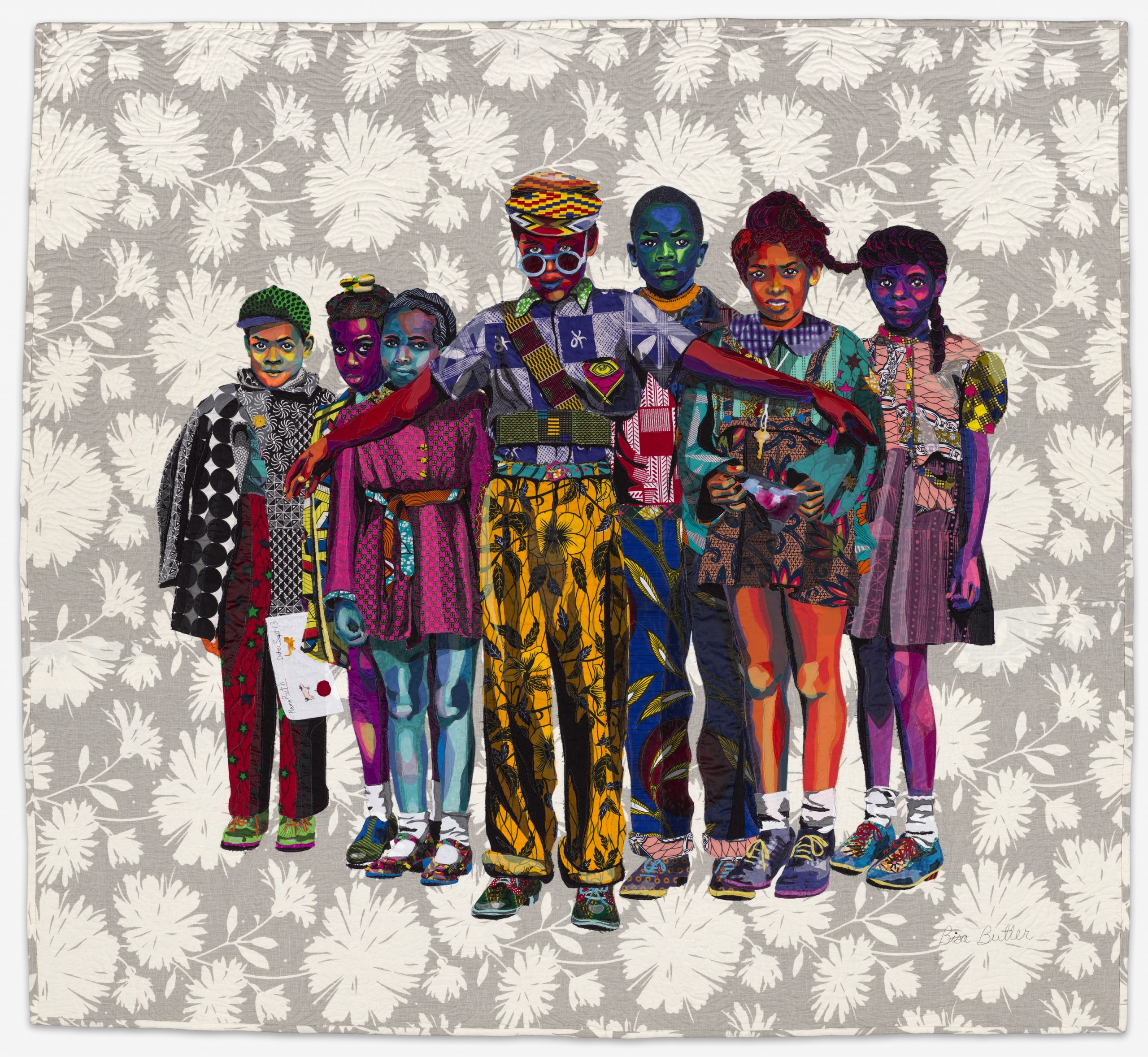

Both “look what we can do” and the “black mundane” are articulated in Butler’s Safety Patrol, 2018, the first work seen in the exhibition. The subject is an ordinary one in the days prior to remote learning: a child wearing a crossing-guard belt helping his fellow students arrive safely at school. Children selected to be crossing guards are typically responsible leaders, good students, and role models for their peers. Numerous Black children fit this description, despite persistent stereotypes to the contrary. Evoking a mother’s outstretched arms as she slams on the car brakes, the crossing guard’s gesture implies protection in allowing his peers access to education.

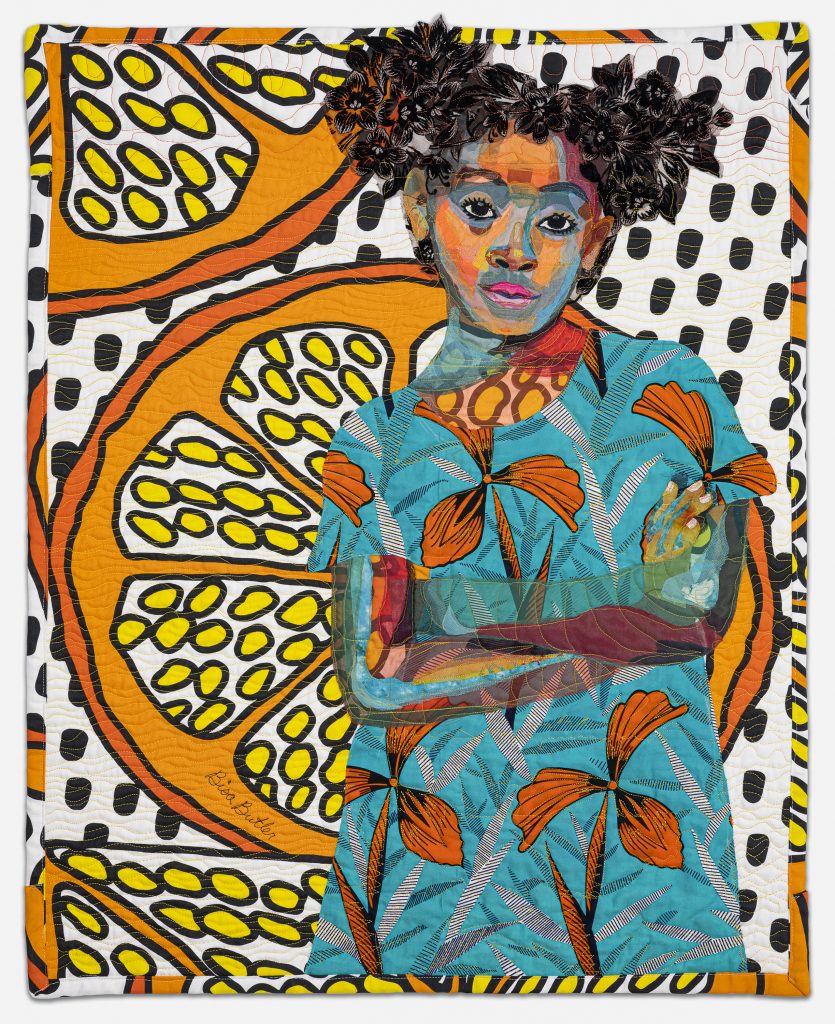

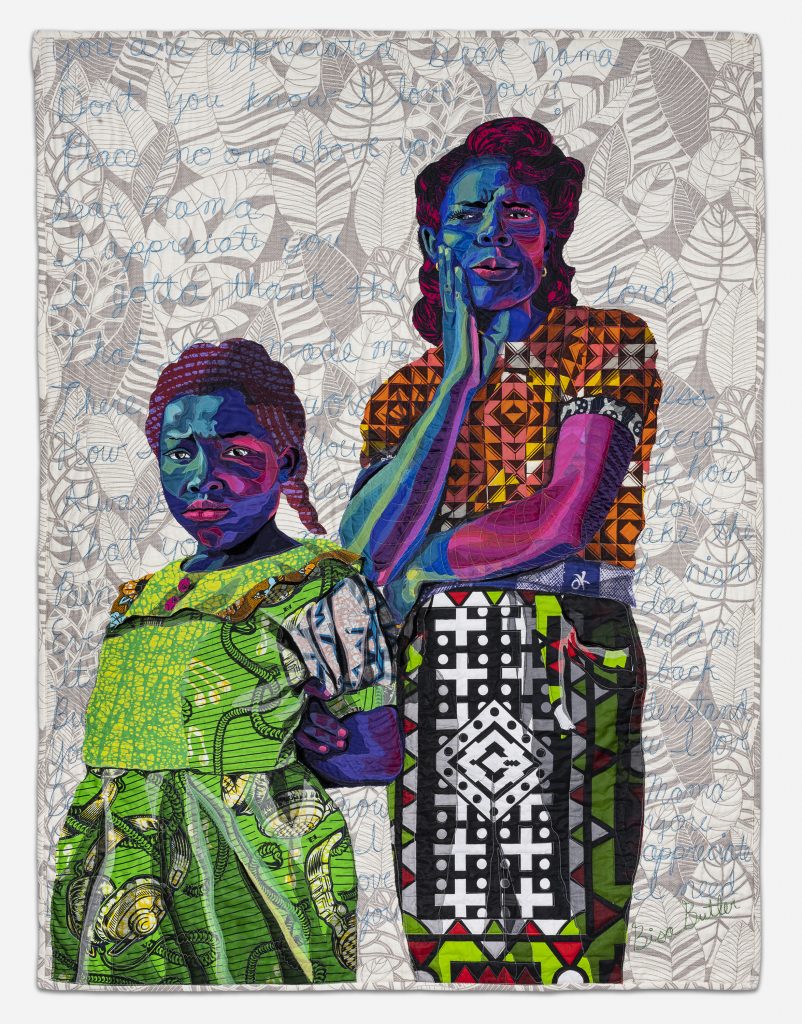

Butler’s artistic process is an interdisciplinary one, as evidenced in Anaya with Oranges, 2017. Photographs, both personal and historic, are the starting point for her figures and compositions. She then layers different fabrics as a traditional quilt-maker might, often using thread not only as a structural component, but also as a material to draw images and words. As seen in Anaya with Oranges, she adds collage elements; applique flowers form Anaya’s hair and complement the floral design of her shirt. Her direct gaze, cocked head, and crossed arms exude attitude and confidence.

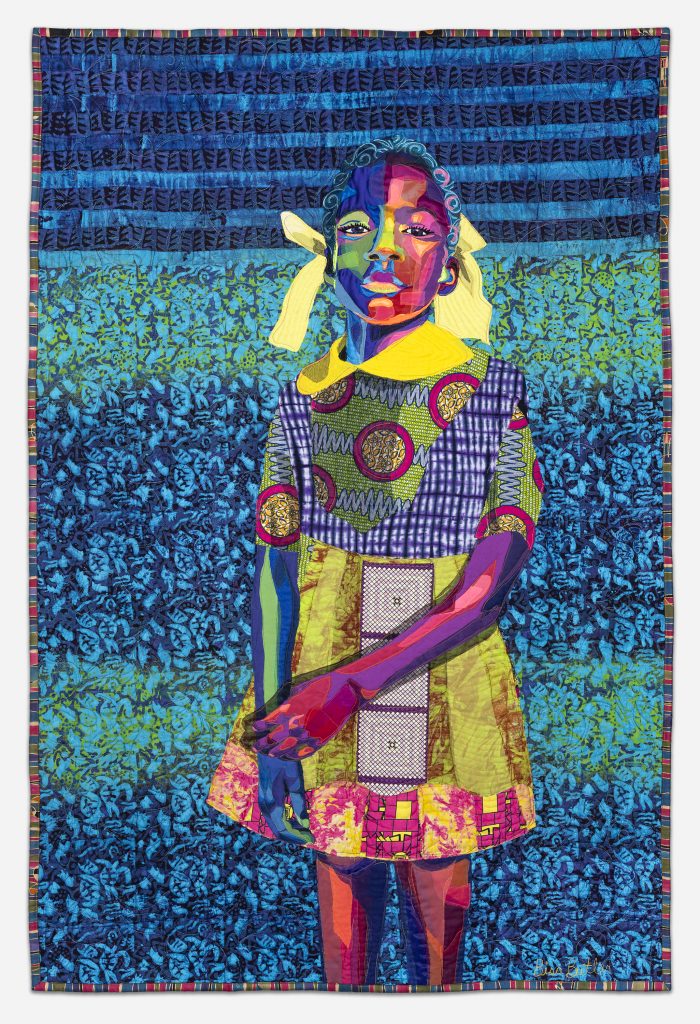

Butler’s earliest works are generally based on photographs of family members and friends. A later piece, The Princess, 2018 references personal imagery as well: a friend who immigrated to the U.S. from Jamaica as a girl. The bright yellow scarf and hair ribbon frame brings prominence to her courageous face.

Subsequently, Butler moves beyond personal photographs, using open-source archives and vintage photos to broaden her narratives. Four Little Girls, September 15, 1963, 2018 refers to the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, depicting the four female subjects in church dress, preening for the camera and/or each other. I Am Not Your Negro, 2019 is based on the Depression-era photograph, Negro in Greenville, Mississippi, by Dorothea Lange, which is shown on the wall label. In this piece, Butler maintains the confident, contemplative posture of the figure from the sourced photograph, but updates his clothing, replacing the patched pants with a fabric covered with airplanes and international clocks to convey worldliness.

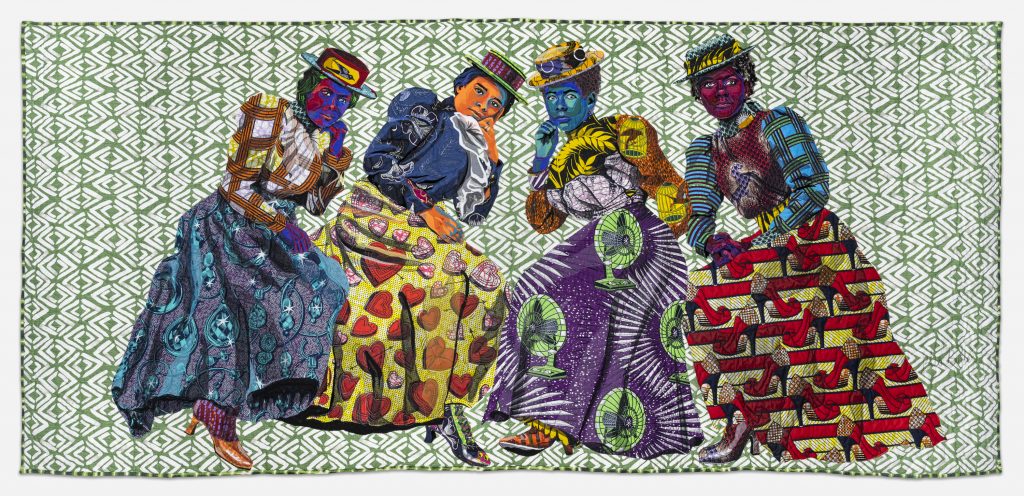

Similarly, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, 2019 is based on a turn-of-the-century photograph of four women seated on the steps of Atlanta University. To attend college at this time as a woman, especially a Black woman, was extraordinary. This status is reflected in the women’s confident postures and gazes. One woman’s blouse literally depicts a caged bird flying free, connoting the opportunities higher education can bring. The woman on the far right wears a skirt made from fabric titled “Michelle’s Shoes”, named after the former First Lady–herself a potent symbol of the power of Black women.

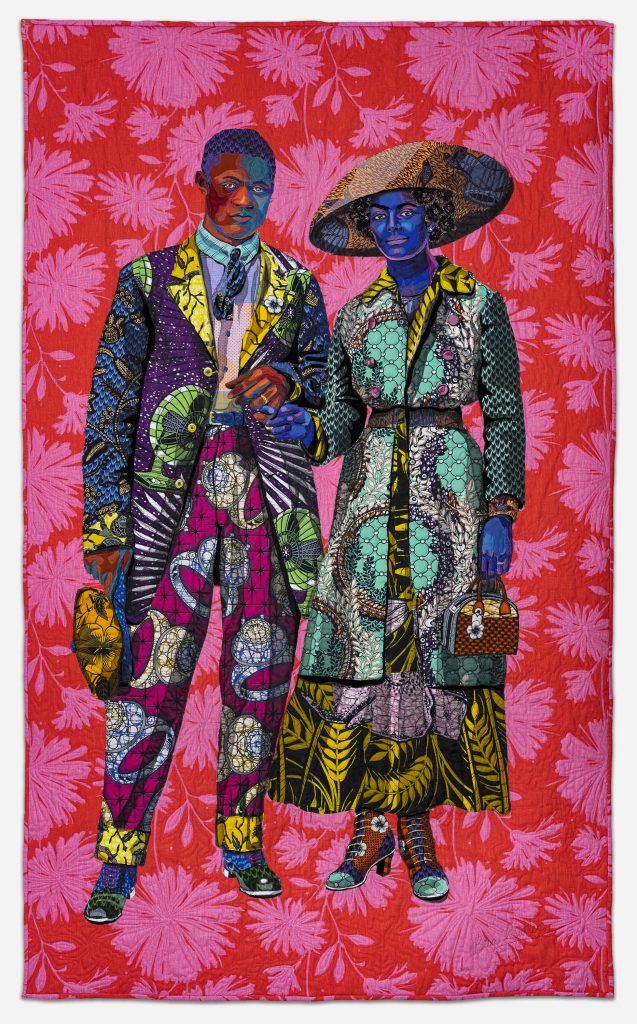

Butler outfits her subjects in bright, patterned clothing that ranges from period to contemporary. Her father was Ghanaian, and she sources many of her fabrics from Ghana, with prints that often define and enhance the narrative. The hallways connecting the galleries are lined in fabric designed by a Dutch firm that manufactures African print textiles and includes examples Butler uses in her portrait quilts. Broom Jumpers, 2019 is an exquisite example of her use of lush, colorful fabrics. Depicting a recently-married couple, the groom’s pants are covered with diamond rings.

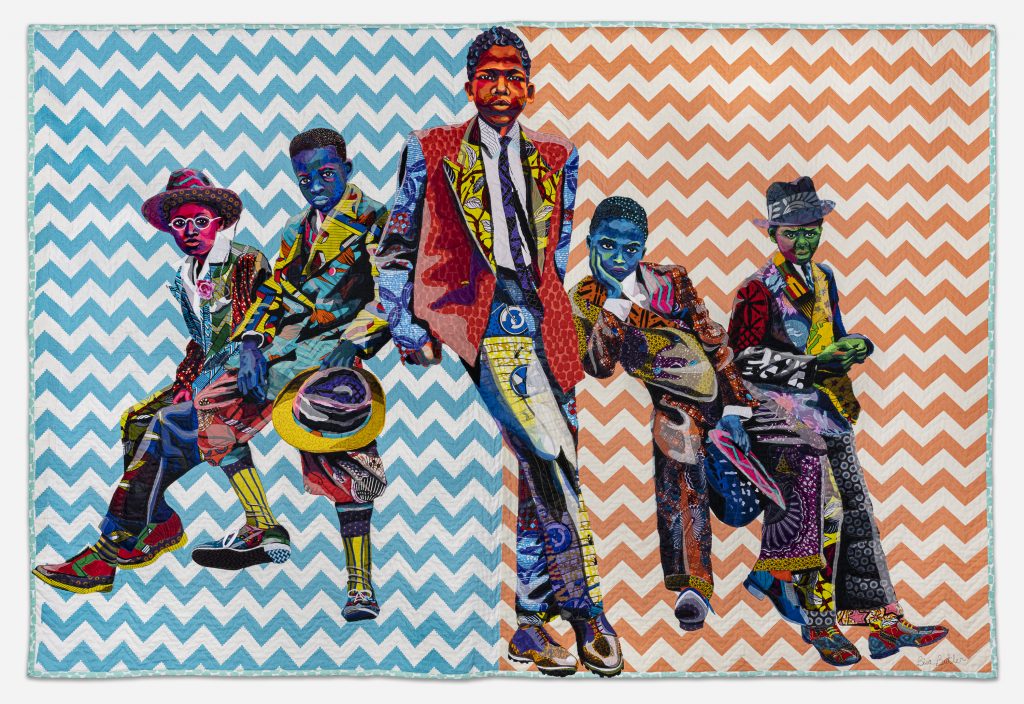

The most salient and unique feature of Butler’s portraits are the unnatural colors of her subjects’ faces. Reminiscent of the jarring, bright colors of German Expressionism and Fauvism, Butler’s referent is more contemporary: the philosophies of Chicago-based AfriCOBRA (the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists). Butler studied painting at Howard University before making textiles her primary medium. One of AfriCOBRA’s founding members, Jeff Donaldson, chaired the art department at Howard. Butler’s work includes several AfriCOBRA principles: positive images of Black people, a play between representation and abstraction, and the use of what the collective referred to as “Kool-Aid” colors, including bright orange, strawberry, cherry, lemon, lime, and grape.

For example, in The Warmth of Other Sons, 2020, the women’s faces are fiery reds and pinks with splashes of blue, while bright orange predominates in the men’s. The work depicts a family traveling to Chicago during the Great Migration. Butler subtly incorporates the narrative into the father’s dress: his shirt includes a log cabin set against plowed fields, while his pants feature the multi-story buildings of a burgeoning city.

The artist presents her subjects with skin tones that are more realistic in a few early works, including One Vote Can Change the World, 2008. Here, the quilt depicts citizens standing in line to vote, one with coffee in hand, set against a backdrop of the American flag. If they were masked and socially-distanced, the piece would be an accurate depiction of the record-setting voter turnout this year. Stitched on the flag is the phrase “one vote can change the world,” reflecting the optimism of Obama’s election.

The Tea, 2017 and Southside Sunday Morning, 2018 are both based on photographs taken during Easter festivities in Chicago in the early 1940s (again, source photos are shown on the wall text). In the latter, the photograph shows boys in their Sunday best, sitting on the hood of a parked car. Butler updates their attire, removes the car and background scenery, and places them on an energetic, vibrant background, maintaining their sophistication and poise while transforming them into youth who are timeless, yet contemporary.

Continuing a long artistic tradition of isolating a subject from their environment, Butler places her figures against backdrops of patterned fabric. Like Rembrandt’s portraits and Catherine Opie’s photographs of queer folk, Butler, too, asks us to focus on the person. Without a context which may imply location, class, or other defining characteristics, we see her subjects as individuals, not representatives of a group or place. Like her forebears, Butler’s subjects are bestowed with dignity through their elegant attire, confident stances, and direct gazes.

Butler succeeds in presenting “look what we can do” through narratives highlighting historic accomplishments and individual triumphs in the Black community. Additionally, her portrait quilts are exquisitely designed and crafted, making the exhibition one worth viewing for both socio-political and aesthetic reasons.

The Art Institute of Chicago is currently closed. Upon cultural institutions reopening, Bisa Butler: Portraits will be on view through April 19, 2021.

Featured image: Bisa Butler. The Safety Patrol, 2018. Cavigga Family Trust Fund. © Bisa Butler. The textile piece portrays a boy wearing colorful clothes, sunglasses, and a crossing guard sash with his arms outstretched. Behind his arms stand six children. They also wear brightly colored clothing. The background is white and gray. Image courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Susan J. Musich spent twenty years as an educator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago communicating fresh perspectives to non-specialist audiences. This experience infuses her approach to writing about art. In addition to freelance writing, Musich serves as a consultant to local foundations and manages the tour program at EXPO CHICAGO.