This piece was created through the Critic-in-Residence program at Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts. This partnership offers an opportunity for a Sixty writer to visit Bemis Center and write a new piece that interacts with one of their current exhibition. The resident also has the opportunity to engage with the many talented artists-in-residence at Bemis Center as well as a local arts writer in order to get a fuller understanding of the arts in this region. Located in Omaha, Nebraska, Bemis Center facilitates the creation, presentation, and understanding of contemporary art through an international residency program, exhibitions, and educational programs.

“It matters what matters we use to think other matters with; it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts, what descriptions describe descriptions, what ties tie ties. It matters what stories make worlds and what worlds make stories.”

– Donna Harraway, “Staying with the Trouble, Making kin in the Chthulucene” (2016)

It is August, and a drought has sapped the lands across Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. Over this summer alone, Midwesterners have experienced several uncharacteristic climatic disturbances, strange phenomena like the “corn sweats”—a process by which corn and soybean crops evaporate and transpire, trapping heat and moisture in the air. With over 80 million acres of genetically altered crops planted annually in the region alone, it’s easy to imagine the disastrous impacts of climate change on regional species diversity, weakening agricultural resilience, and increased stressors on regional lake water resources, all of which converge at the confluence of the Great Lakes and Great Plains.

In this year alone, two uncontrollable wildfires scorched over 30,000 acres of land in Northeast Minnesota, 320 wildfires have engulfed Wisconsin since June, and an intense heat wave, coupled with flash floods, hit Milwaukee and Chicago. The idea of large-scale and small-scale, cosmopolitan and rural, stems from the legacy of colonialism have led to extractive land development policies that go as far back as the Homestead Act of 1862, that encouraged small-scale monoculture at the expense of Indigenous displacement. Land Grants for railroads similarly incentivized infrastructural development for export oriented large-scale monoculture crop, as Indigenous knowledge systems began to be erased from the Western imaginary, in lieu of man’s control over natural processes and power.

Moving away from the (individualistic) notion of humans being simply passive consumers to being present as conscious citizens, requires a shift in both attitude and understanding about our daily actions and how they impact the cumulative carbon footprint. While questions of social reform, industrial regulation, and political development slip into the realm of semi–truths and part-falsehoods, artists, designers, and creatives act as a bellwether. As first responders in the face of a large-scale climate crisis, the problem of climate awareness comes down to a larger cultural crisis, making it clear that one must begin to dismantle disciplinary limitations that sever our collective economic, cultural, and political well-being.

I hop across scorched cobblestone to the Bemis Center in Omaha, NE. The weather reads 50’ celsius with a humidity index of 46%, higher than the historical average for August. Entering the former agricultural factory and distribution center renovated to house Bemis Center’s Art and Sound Studios and Performance spaces, one encounters Asad Raza’s, Orientation, 2022, at the main entrance. Modeled on New Delhi’s astronomical observatory circa 1724, Jantar Mantar, Orientation is a neo-Yantra (numerical-geometric) architecture built of sand, plaster, reed, rubble, and crushed Quagga mussel shells trawled from Lake Erie. Initially commissioned for Front Triennial 2022, a once-in-three-years public art event spread across North East Ohio, the sculpture is both a park slide and an observatory space, evoking a sense of playfulness and curiosity. As the first of a two-part conversation, with an accompanying video, Delegation, 2022, Raza’s multifaceted approach to working collectively with groups of scientists, student researchers, musicians, poets, and artists, studies migratory water routes across Lake Erie. Setting sail from Buffalo to Cleveland, to study the many moods and movements of Eries water, sweeping shots of the lake, abandoned factories along its shoreline, lakefront mansions, and graffiti’d architectures, juxtapose against rhythmic shots of wilderness and sunsets. Scored by traveling musicians, Delegation, captures a spatialized, multi-layered composition that incorporates Indigenous and Seneca oral traditions performed within the architecture of an old church. The coexistence of multiple cultures and multiple natural systems renders a soulful connection between people and place. Raza conjures a cyclical awareness of migration patterns from the 18th century onwards, telling of what is gained and what is lost in moving Westward.

Living in the Midwest, surrounded by complex forest, wetland, and prairie ecosystems, there is an inevitability that one quickly realizes that we, as humans, embody ecologies in and of ourselves. This interconnectedness is one of the central theses of “Great Lakes, Great Plains”, an exhibition that invites 21 artists curated by Bemis Center’s Chief Curator + Director of Programs, Rachel Adams, to present a matrix of ways in which nature and culture meet to consider climate change as a broader social, cultural and economic issue. Centering the cognitive and sensory capacities of human and animal life, the works focus on recent climatic stressors across what has come to be known as “flyover country”. One glimpses the ecological wealth of a region privy to the abundance of groundwater due to the presence of the 2-6 million year-old Ogallala Aquifer, as Adam’s explains how, “People often take for granted what has been a given their entire lives. They cannot see the immediate consequences of their actions on a larger scale, but locals are beginning to feel its (effects),” she says wiping her brow. Taken by the immensity of the Missouri River nearby, my mind wanders to large swathes of the world deprived of fresh potable water. In my generation alone, we have moved from the speculative to a full-blown problem-solving mode of questioning what steps, responses, and interventions grow ever more necessary in response to dwindling and contaminated water resources, not just in Middle and Central America, but across the world.

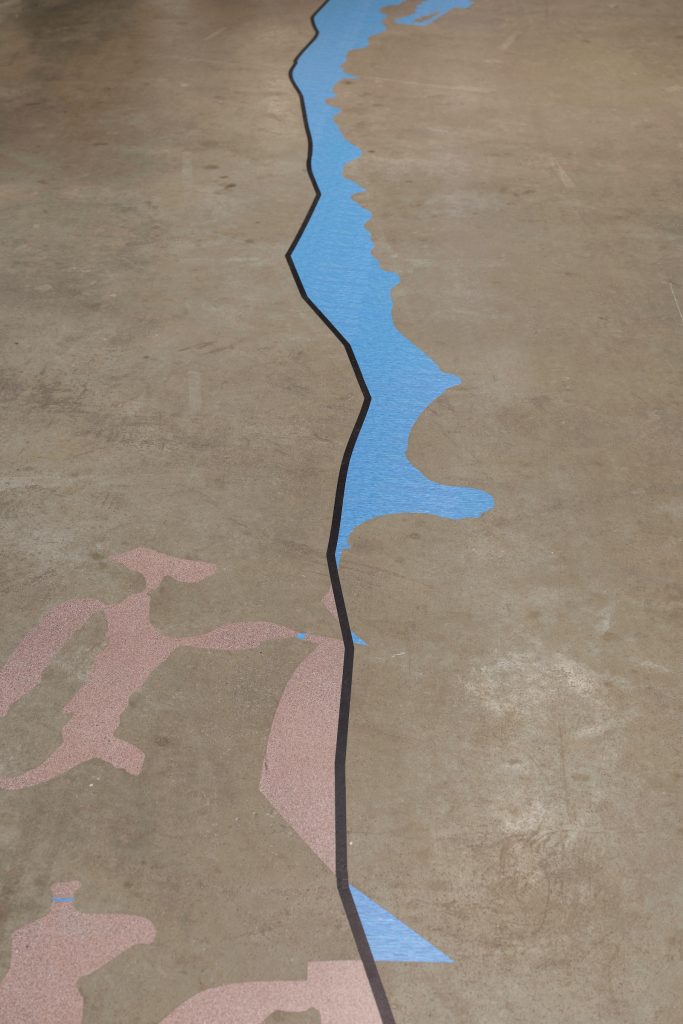

Adams steps out of an anthropocentric, human-centered worldview, extending systemic questions to embodied agents; ancestors, animals, and plants alike are coexisting entities along rivers and lakes. Elders from the Lakota, Standing Rock Sioux, Crane, Anishnabe, and Miami tribes, act as steadying voices in JeeYeun Lee’s, Shore Land, 2023. The piece consists of a linear floor vinyl decal running the entire length of a central corridor, representing changes in the Chicago lakefront shoreline since 1820. Speaking of the sovereignty of land and water along Lake Michigan through their stories, songs, and treaties, Billie Warren of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi, speaks on the autonomous rights of water. Explaining how Lake Michigan’s manmade coastline is neither city nor public land, but a construction that extends beyond the boundary of 5 million acres of land East of the Mississippi ceded by Native peoples in the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, the lakefront is advocated for as a liminal, sovereign space, a site of deep spiritual significance and water culture, disturbed by dredging, damming, and other extractive logics that have harmed animal habitats while degrading wetland ecosystems.

A premonitory rainbow-hued stoneware map of North America holds large blue, green, and red ballooning weather indicators in Jess Benjamin’s The Future of Drought, 2012-2025. Questioning the role of cartography in the domination and exploitation of Indigenous peoples, I veer towards a series of over-painted pulp maps, speckled in fluorescent green and black monoprint abstractions. Timothy Frerichs, Bloom Maps, 2020, charts cyanobacterial spreads from satellite imagery across the warming waters of Lake Erie. Formed by the run-off of agricultural fertilizer, algae blooms threaten drinking water and aquatic life, directly impacting public health. Deep black-inks pool at the surface like weeds or rotting dead fish. My mind travels to my hometown, Bombay, and to other coastal cities surrounded by warming waters that are suffering the same fate. As algae blooms increase manifold, there is a need for public awareness on shared issues of water quality, both here and there. As geological timelines criss-cross within, my eyes move to the ground, attempting to shake off the weight of climate anxiety. An endless stream of words runs beneath my feet, leading me from one gallery to the next in Trey Moody’s Thread of Water. A trickle of poetry that provides a way-finder out of apocalyptic isolation.

Two panoramic photographs sit on wall-mounted shelves as testament to the impact of centuries of Indigenous dispossession. Dana Fritz’s Post-fire Postscript, 2024, and Field Guide to a Hybrid Landscape, 2025, stage black and white accordion-folded images of ashen woods and dried grasses against deep summer, post-fire, and wintery snow landscapes. Fritz’ studies regarding the impacts of extractive economic practices in one of the oldest hand-planted forests of the Great Plains, the Nebraska National Forest, reveal endless panoramas of above-ground woodland disturbed by an unsustainable rate of forest conversion and timber extraction. Commemorating forgotten Indigenous land management practices, solemn images of carbonized timber represent the relatively high cost of cultural erasure tethered to industry practices.

Latoya Ruby Frazier’s Flint is Family, 2016, centers around the psychological landscape of the people of Flint, Michigan, who have been living with and consuming contaminated water since 2014. When Governor Rick Snyder switched the town’s water supply to run through a defunct water treatment plant, civilians had to reclaim their survival, taking civic water management, storage, and circulation into their own hands. As generations continue to suffer the fallout of dangerously high levels of lead poisoning, Ruby Frazier captures the tenderness of a community against a frightening political landscape. One of eight black and white portraits shows a young child standing by the side of the road, waiting for Obama’s cavalcade to pass by. Holding a ‘WANTED’ poster with Snyder’s name and profile, he’s framed by family and friends escaping the rain under two barren trees. In another, Flint community members stand with refilled water jugs near an Atmospheric Water Generator set up by and for the community. The seminal series of photographic portraits questions state-sanctioned Black death through systemic community divestment. Flint is Family, 2016-2019, continues to haunt all who understand how structural inequalities undermine Black life and mobility across the post-industrial Midwest.

Opposing the cleave and fracture of privatized natural water systems towards instead National wetland banking systems, Rosalinda Borcilā & Andrea Carlson’s Hydrologic Unit Code 071200, 2023, is a 5-channel video abstraction that splices together images of wetlands, marshes, and monuments from Origins Park and Portage National Heritage site to initiate a dialogue between the past and present as active memorial sites of human conflict. Videos of hydrologic wetbank sites, dams, and levees from Indian Creek, Otter Creek Bend, Syaquay, and more interpolate texts from governmental land agreements, public parklands, and other bureaucratic governance documents. Inverting and collapsing on a central vertical median, the video radiates right to left (into the future), and left to right (into the past). This implied movement into abstraction goes against Western logic of expert-driven market trading, as words actively pushing Native people’s rights out of the formation of “national interests”, Borcilā & Carlson create a detournément between documentary and the absurdity of techno-financial bloodlust, to reveal wetland credit banking as a new frontier for Indigenous ecocide.

Tali Weinberg’s Heat Waves/Water Falls, 2024, is one in a series of sculptures featured in “Great Lakes, Great Plains” that visualizes climate data and statistics against material circuitry. A curtain of petrochemical-derived medical tubing hangs wrapped in plant-dyed thread, communicating data from the NOAA temperature index from across 18 river basins. Segments of earth-reds and moss greens indicate the sheer scale of interconnected crises between ecologies and communities. In adjoining galleries, two stoneware maps by Jess Benjamin, and several embroidered, patterned fabric pieces by Karen Reimer, visualize data on rising water temperatures and the effects of toxic contamination on the rapidly depleting Aquifer near Reimer’s hometown in Kansas.

Adopting the embodied ability of camouflage as reptile or fish, several iridescent hand-cut ponchos compose Hoesy Corona’s Climate Ponchos, 2023. The ponchos invoke hope and protection through brightly colored silhouettes of travelers, wild flora, and fauna. Pop-inspired landscapes glaringly enunciate the violent processes of colonial conquest, as the artist draws from personal history and experience of LatinX queerness. Corona’s iridescent eccentricities support a hypnotic voyage, a non-normative view of the world under the protective cover of technicolor futurist drag.

The idea of the climate crisis as something outside or separate from us assumes the ontological “other”, separating one from the other. This is perpetuated by laws on private land ownership and technological governance that plague our daily interactions. Alternatively, artists Bently Spang and Anna Scime posit a transmaterial ecological understanding, following Indigenous impetus and ecological synergetic flows. As a member of the Tsitsistas/Suhtai nation, Spang’s War Shirt #6 Waterways, 2017 is a 16-channel video installation that aspires to connect waterways along over 500,000 acres of Southeastern Montana. Placed horizontally and vertically, monitors come together to form a geometric patterned shirt-like form, with arms outstretched. Smaller iPads tassel the sculptures’ edges, as Spang traverses us through rains, rivers, and studies of native species along the plains. As human stakeholders of water as a resource, the work seems to reframe the terms on which we understand the sensitivity of water. In an act of radical alterity, Spang’s non-linear edit provides an honest witness to the movement of water, foregrounding a required mutual reciprocity for us to receive water as a sentient resource.

Tapping into the intelligence of endangered species, Scime’s videos of Lake Sturgeon move us through the lifecycles of one of the most endangered species on earth: Wild Sturgeon. Scime worked alongside ecological scientists and biological researchers to explore the profound effects the species has on the ecosystems it inhabits across Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. Underwater shots of spawning rituals, studies of habitat, and a careful procedure of massaging the abdomen of Sturgeon to reveal its dietary habits, helping in rewilding efforts. Documentary as a form reintegrates parts of reality that have been excerpted from dominant epistemologies. Scime’s studies feel like an ode to human-fish relations dating as far back as the Babylonian empire, times when the fertility of humankind was contingent on the fertility of water, crops, and interspecies well-being. Her sturgeon begin to show us a parallel timeline; an alternative course necessary for interspecies evolution.

Excerpts from Colleen Thurston’s documentary, Drowned Land, 2025, follows women who live near the Kiamachi River, and their fight to live in harmony with it. Twice-dammed in the state of Oklahoma, Thurston juxtaposes the lived narratives of Choctaw women against her personal entwinement with the river, in an attempt to rematriate the land for the sake of saving local populations from resource deprivation. As Texas corporations continue to commodify water preserves for hydroelectric development, Thurston harnesses interviews as spaces for deep listening, to decolonize a historically oppressed land and people.

Several screens around the Bemis Center provide captivating portraits of nature’s rhythmic flows from Platte Basin Timelapse. The watershed, spread across the heart of North America, collects most of the groundwater and snowmelt that supports the lives of millions of people, plants, and animal species across the country. We watch the breathtaking annual migration of sandhill cranes, as birds sweep across waterbodies from sunrise to sunset. Timelapses of rivers and watersheds through the seasons reveal ecosystems above and below the waterline; beavers, bobcats, fish, and amphibians all moving in rhythmically attuned the water levels across grasslands, mountains, and wetlands. In another, a curvature of snow melts as lakes rise and swell, retreating in colder months, revealing nature’s great artistry.

Teresa Baker’s Buffalo Bird Woman, 2024, and Missouri River, 2022, shift our vantage point from the horizontal of viewing land to an aerial view of the earth. Hovering above, Baker employs bright blue astroturf as land, shape, and material, delineating the artifice of manmade landscaping. Drawing a rudimentary map of water as a source of irrigation, transportation, hunting, and trade, Baker embroiders blue-green surfaces with brightly colored yarns to build irregular geometric shapes in concentric lines. Directly mounted to the gallery wall, each composition reads as a territory, reminiscent of a bird’s-eye view of hectares of agricultural land surrounding Omaha. As abstract painting, sculpture, and womens-craft, Baker’s high-saturation plasticized palettes point to consumer plastics choking the biodiversity of ecological hotspots. How do the silent threats of material waste raise questions of how our daily actions shape future life-systems?

If one were to rethink an ethical frame to fully comprehend the interrelatedness of ecologies in the world, one would have to begin to accept the sentience of all living and non-living things. How could this shift in awareness affect the pace of human progress? Could a slower mode of being in-time, or with-place, disrupt power relations that uphold systemic injustices? Other Channels, 2025 serves as example. In the piece, sound artist and engineer, Nadia Botello, asks us to pay attention to what water is “saying for itself.” Bringing the pure presence of water from the Missouri River into the gallery in a 16-inch square water tank, visitors are encouraged to physically engage with a 34-minute string quartet (commissioned by Bemis in 2021) through a speaker placed at the bottom of the tank. Marking physical changes experienced by the river, I follow suit and place my cheek to the cold glass while cupping two walled-in edges. “Tell me,” I whisper, “how can we co-exist?” Met with a low hum, I realize there is much to learn from being present in slow attentive landscapes before positing this question.

Drawing from insights found between works in “Great Lakes, Great Plains,” I am struck by the deep empathy of the artists and curator in facing issues of water conservation at times of regional and national upheaval. As non-Western nations wake up to exploitative trade relations shared with the West, human and non-human systems are also learning that our ecological and cultural survival demands we adopt a non-hierarchical, non-extractive, intersectional belief system. Between theory and practice, language and representation, we must co-construct how we articulate the complexity of systemic realities. In telling and re-telling stories from multi-agent perspectives, “Great Lakes, Great Plains” calls for a cross-section of research and expertise in and around the arts, to overcome the destructive self-interest of humanity under neoliberalism. In such collective witnessing, maybe even mourning, artists and visitors are inspired to reflect and claim collective responsibility for the region and its strained water systems. As a call to direct action, to tell stories, to disrupt mechanisms of extractive control that maintain destructive subject/object relations, it is incumbent on each of us to reimagine paths outside of the dominant discourse to reach the core of the causes of our panoptic ecological crisis.

About the author: Pia Singh is an independent curator and art writer from Bombay, IN, living and working in Chicago, IL. Bolstering artistic practices through exhibitions, art criticism, and community organizing, Singh has been curating experimental practices with artist-run spaces, institutional, and commercial galleries for over 15 years. Her research focuses on community-engaged arts practices that lie at the intersection of contemporary art and design, to allow us to consider pedagogical hierarchies within and outside of which artists aspire strive for systemic change. Singh is published by Sixty Inches from Center, Chicago Reader, Brooklyn Rail, Frieze Magazine, and has been featured in Hyperallergic, Cultured Magazine, Tussle, and ArtIndia.